The South Korean economy is a highly developed mixed economy, holding 10th place by nominal GDP, which is one of the most successful and flexible in the world due to its high-tech industries. However, the country’s economy is characterized by a unique feature that is not seen to such an extent anywhere in the world, known as chaebol. Chaebols are approximately a dozen of family-run conglomerates of internationally known brands that dominate the majority of South Korea’s economic output but also hold significant social and political influence. Chaebols have raised the economy and life quality in South Korea and have become an inherent part of the culture. However, this approach to business in the country has faced significant criticism due to its power and corruption, comparable to the monopolies of the U.S. in the late 19th century. This paper argues that chaebols ultimately benefit South Korea’s economy and contribute to its rapid growth and relative stability, but greater regulation is necessary to avoid the firms from illegally manipulating policy and leveraging political influence in unethical ways.

Origin and Background

A chaebol is an English transliteration of the Korean words chae and bol (재벌). These literally translate as ‘wealth clan’ or a less literal interpretation would be a plutocracy, rich family, or even monopoly. It is believed that chaebol was influenced by a similar structure in Japan known as zaibatsu. These were also family-controlled conglomerates that were prevalent in the Japanese economy prior to World War 2 before being disbanded as part of the U.S. post-war de-facto control of the country (Pae, 2019). In 1963, Park Chung-hee took over leadership in South Korea after a military coup and began a rapid ‘guided capitalism’ modernization program. The chaebol structure was intentional and promoted by the leadership to fast-track economic development, with these government-selected companies taking on major projects with federal financing and loans (Albert, 2018).

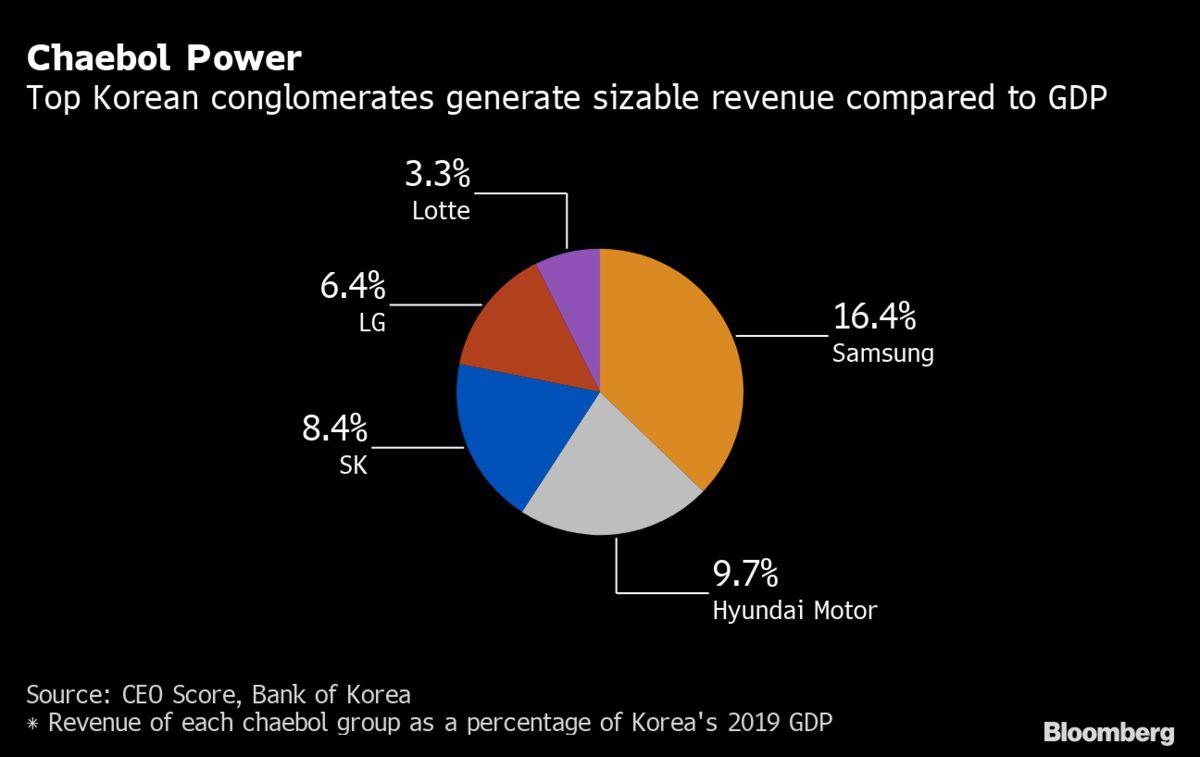

The chaebol structure placed family members of the founding company family in ownership and management positions maintaining control of all affiliates. Due to the cooperation with the government for subsidies, loans, and taxes, the chaebols saw significant economic success but also became pillars of the country’s economy and culture. According to Korea’s Fair Trade Commission, there are approximately 45 conglomerates in the modern-day that fit the chaebol definition. However, in reality, the biggest power and money lies in the largest 12-15, with the top 10 owning a whopping 27% of all business assets in the country (Albert, 2018).

Practical Examples

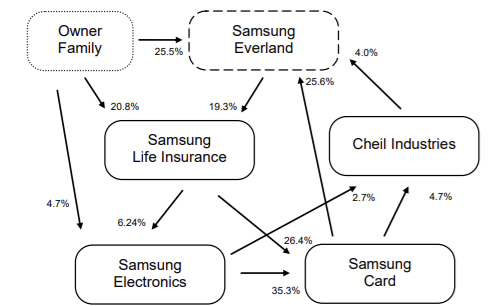

As established, a chaebol is a “collective of formally independent firms” under a “common administrative and financial control” of a dynasty or family (Murillo & Sung, 2013). The three defining characteristics of a chaebol are: 1) multiple affiliated firms in diverse industries, 2) ownership and control lie in a dominant family, and 3) the business conglomerate accounts for a significant percentage of the national economy (Murillo & Sung, 2013). Day-to-day operations are overseen by professional managers and executives responsible for the individual firms, but in reality, they are controlled by a single chongsu, an unofficial appointed general manager who makes the large and final corporate decisions for the syndicate. The chongsu is the representative of the owner’s family and holds the majority of shares. While this individual has no formal power, they exert control through vast cross-shareholding (Murillo & Sung, 2013).

While professional managers are becoming more prevalent in the leadership of Korean chaebols, the structure remains family-owned and managed across these top corporations. Chaebols expand family ties to business through marriage protecting the family’s power as well as using strong political influence as multiple scandals over decades have shown bribery of political leaders (Albert, 2018). For example, the arrest of the de facto leader of Samsung Lee Jae-Yong in mid-2020 for corruption of the former president Park Geun-Hye as well as accounting fraud to help consolidate power over the chaebol (Byford, 2020).

Although these are top-profile scandals, they represent some of the common practices used by chaebols over the decades. There is also a range of financial practices common for chaebols. These include rapid overinvestment or high-risk investment, often resulting in higher market-value-based debt ratios than usual for corporations, reliant on government subsidies as they make capital expenditures even in declining industries (Murillo & Sung, 2013). Chaebols also make investment diversifications that are not financially rational, aimed at avoiding the political and economic risk of losing control over the chaebol, transferring power to heirs, increasing the chongsu’s image in society, and accruing managerial power by creating more firms (Murillo & Sung, 2013). Finally, there is overwhelming internal trading and tunneling among chaebol affiliates. Firms buy products and services from within the sister companies in the chaebol, even when external firms may offer better rates – pursuing a strategy of profit stability and maximization for the conglomerate as a whole, but may impact shareholders of a particular firm (Murillo & Sung, 2013).

Benefits to Economy

Historically, chaebols were the cause that propelled South Korea to become a global economic power, technological innovator, and economically self-reliant. The practice protected domestic industries from external competition, and eventually, chaebols expanded into multiple industrial sectors and entered lucrative international markets, providing fuel for the country’s economy (Albert, 2018). South Korea maintains over 40% GDP exports, which is one of the highest rates globally, and the average income rose from $120 annually in 1961 to $27,000 in modern-day, lifting millions out of poverty (Albert, 2018). Chaebols are responsible for the majority of the country’s investment in research and development as well as production. The chaebol structure has been attributed to the limited economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the country. South Korea’s GDP declined just 1% which is inconsequential compared to other developed economies, largely due to the government-private sector partnership in containing the pandemic, and the successes of these large companies to continue the economy running through exports, especially in the high-tech industries (Ferrier, 2021).

Impact on Business Growth

Due to the concentration of the economic power among these top chaebols, business growth in South Korea is by extension limited to the subsidiaries within these companies which benefit from the financing and support of both the government and access to the market (Albert, 2018). That makes South Korea increasingly reliant on the success of chaebols, which is seen as problematic given some of the high-risk, and even illegal practices that they undertake in their operations as discussed earlier. This has given rise to criticism and concern from economists that chaebols essentially use their monopolistic positions to squeeze small and medium enterprises (SMEs) out of the market by either pricing them out or through hostile takeovers (Albert, 2018).

While it is not an uncommon aspect across the world for these large multinational corporations to dominate the market, due to the diverse subsidiaries of chaebols in South Korea, virtually all possible industries of the market are controlled, creating a highly predatory environment. Despite the size of chaebols, it is actually SMEs that provide the majority of the country’s employment, and because of these practices, they cannot grow. Furthermore, there is a significant wage gap, with average pay at SMEs being only 63% of chaebol employees (Albert, 2018). However, because chaebols maximize income and utilize innovative technology for automated production, they are hiring less and less, creating concern about growing income inequality in the country and high youth unemployment rates. Overall, business growth is highly stifled due to the chaebol structure of the economy (Albert, 2018). In combination with large-scale corruption associated with chaebols, there is declining social trust, wasteful spending, and reduced economic competitiveness. It often forces the government to come in with large bailouts due to poor decision-making of chaebols that are seeming ‘too big to fail.’

Pros and Cons of Chaebol

As mentioned, chaebols play a key part in South Korea’s economy allowing for its high GDP due to exports. Chaebols present various benefits as part of their structure, which includes scale and scope of production, vast knowledge in industries, diversification of businesses and economies, well-recognized reputation and brand names, and availability of capital for investment and research (Park et al., 2008). However, there are multiple negative impacts that have emerged as a result of chaebols in the modern day.

One of the major concerns is wealth inequality and wage disparity. Despite the top 64 chaebols accounting for 84% of the country’s GDP, it only represents 10% of jobs (Ferrier, 2021). There is a significant belief that chaebols are holding an excessive concentration of wealth, at the expense of the working class Korean people and a labor force that is struggling, particularly in the context of the pandemic and chaebols stifling SMEs. Another major concern is the illegal and improper relationships that have occurred between government and chaebols, which are seen as detrimental to the public interest and corrupt, especially considering that chaebols are no longer driving growth and jobs as they have in the past (Ferrier, 2021). Overall, economists and politicians argue that the chaebol is a cultural relic that is ill-suited for the 21st century. The shares of chaebol-linked companies trade much lower multiples of earnings than their Western counterparts (known as the Korean discount) due to concerns of cross-ownership and cronyism, which is counterproductive in the modern corporate world (Pae, 2019).

Future of Chaebols

Despite the many criticisms, chaebols are an inherently critical element of the Korean economy, and by extension society, national security, and stability. It is unlikely that they will disappear any time in the future as most of the largest chaebols are vital international firms. However, reforms are likely on the way as the South Korean government is facing a reckoning and public backlash, especially on the back of the Samsung executive scandal (Kim, 2020). The policy will aim at reforming the corporate governance of chaebols, with much greater transparency and a decreased behind-the-scenes influence of these conglomerates. For example, the largest shareholders in a chaebol can no longer be auditors who share their interests or owe business favors. Potentially, anti-monopoly-style legislation will also allow South Korea’s economy to diversify more in terms of promoting competition and the rise of small-and-medium-sized businesses, making progress toward a healthier and more robust economy (Kim, 2020).

While expectedly there is significant pushback from the chaebols and their respective trade associations, some conglomerates are recognizing that change is on the way. For example, Samsung officially appointed some new executives, including some outside the family, while LG instituted a more transparent corporate governance which eliminates cross-shareholding and ensures board independence (Hussain, 2007). Generally, it is recognized that for these chaebols to succeed in the future and unleash the full potential of South Korea’s economy, reforms need to be implemented. Government policy and partnerships built with international partners can prevent some of the manipulative or hidden business practices that have been ongoing for decades.

References

Albert, E. (2018). South Korea’s chaebol challenge. Web.

Byford, S. (2020). Samsung heir Lee may be arrested soon on new corruption charges. The Verge. Web.

Ferrier, K. (2021). South Korea’s vision for a more inclusive pandemic recovery. The Diplomat. Web.

Hussain, T. (2007). What’s a chaebol to do? Strategy-business. Web.

Kim, S. (2020). Korea set to crack down on chaebols with corporate reform. BloombergQuint. Web.

Murillo, D., & Sung, Y. (2013). Understanding Korean capitalism: Chaebols and their corporate governance. Web.

Pae, P. (2019). South Korea’s chaebol. Bloomberg. Web.

Park, H. Y., Shin, G-C., & Suh, S. H. (2008). Advantages and shortcomings of Korean chaebols. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 7(1), 57-66. Web.