Executive summary

The Tasmanian forestry industry is shifting towards efficiency in processing timber. The effectiveness of subsidies or tariffs depends on the elasticity of supply and demand. Low elasticity of supply will make both policies ineffective. The high elasticity of supply becomes effective even when the demand in the local market is inelastic because the global demand is elastic.

Emerging markets offer an opportunity for a highly elastic supply. Subsidies withdraw resources from alternative uses when tariffs raise funds for the government. As a result, the government may be more inclined to use tariffs than subsidies. Another reason that could make the government choose tariffs is the inelasticity of supply. Timber prices have become more stable in recent years than they were before the 1990s. The global market has brought more concerns for competitiveness.

Tasmanians have witnessed the closure of processing facilities that were considered inefficient in an attempt to increase competitiveness in the global market. The upward export trend is likely to continue as wet eucalypt forests provide a fast-growing forest advantage. The future of the Tasmanian forest industry will be dependent on investment in plantations. More activism from environmentalist will ensure that reserved forests are not used for the supply of timber.

Introduction

The Tasmanian forestry industry is shifting towards efficiency in processing timber. The Tasmania forestry industry is supported by forests in wet and dry areas. Most of the forested land in Tasmania falls under the control of the government. Public and private forests cover 49% of the land in Tasmania. Reserves account for 47% of forest cover in Tasmania. The industry employs about 6,300 people and contributes about $1.4 to $1.6 billion annually to the Australian economy (FIAT, 2014). Trees that reach a height of 85 metres are protected through a tall-trees policy. The Tasmania forestry industry experienced a decline in output in recent years.

The industry is more reliant on native forests than on forest plantations. There is a set of species that are classified as non-commercial because of previous harvesting techniques that made their current quantities unviable. There is a global market where consumers are far away from the areas of production. The global forest industry characteristic is production-oriented. People purchase what is available on the market. China is the main importer of hardwood timber, and the European Union is the main importer of wood pellets.

The global industry is characterized by low profitability. There are high logging costs and a long period before trees mature for harvesting. The low barriers to entry have enabled the industry to have a large number of small-scale producers. A large number of small-scale producers makes it difficult to control prices for high profitability. The substitutes and complements may change according to emerging technologies. The global forestry industry is characterized by protests against the harvesting of natural forests in many countries.

Both the private and public sectors are required to balance between revenues from harvested trees and the ecological needs of the surrounding areas. By imposing tariffs on non-Tasmanian timber products, there will be an increase in the price of products made from non-Tasmanian timber. Australians will increase the purchase of products from Tasmanian forests as they will appear cheaper. The policy is more effective when the supply and demand of timber are highly elastic to changes in price.

Low elasticity of supply and demand may cause Australians to continue purchasing non-Tasmanian timber products after the government has imposed tariffs on imported timber products. Subsidies issued to producers of Tasmania timber reduce the prices of products. They encourage more production and consumption of Tasmanian timber products. Activists would want fewer trees harvested in Tasmania, especially from native forests. The policy can be more effective when the supply for timber from the Tasmanian unnatural forest is elastic.

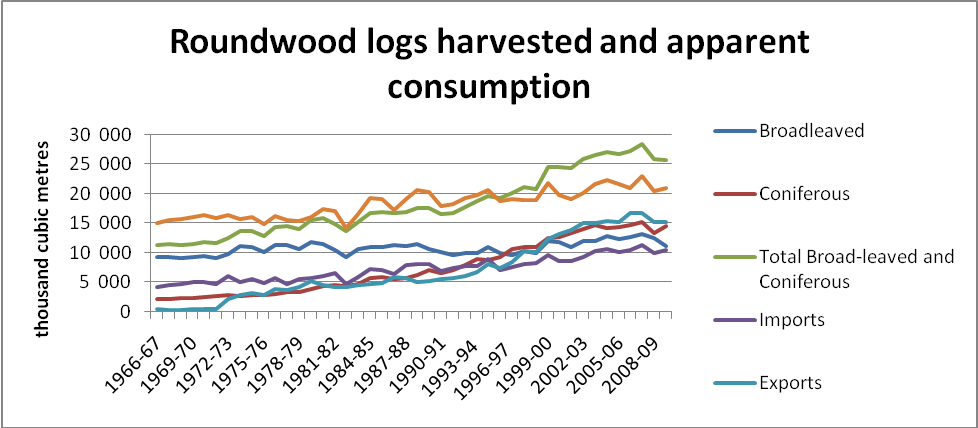

In most cases, the supply has low elasticity. Increasing the felling of trees to match increasing demand will create a shortage in the future because trees take a long period of time to mature. The total timber consumption has increased continuously since the 1960s. The increase in consumption is driven by the increase in population. The apparent consumption per person has declined. It indicates increases in consumption are derived from population growth. In recent years, the export of woodchip has declined from both broadleaved and coniferous types. Alternative uses have brought in more efficient methods of processing.

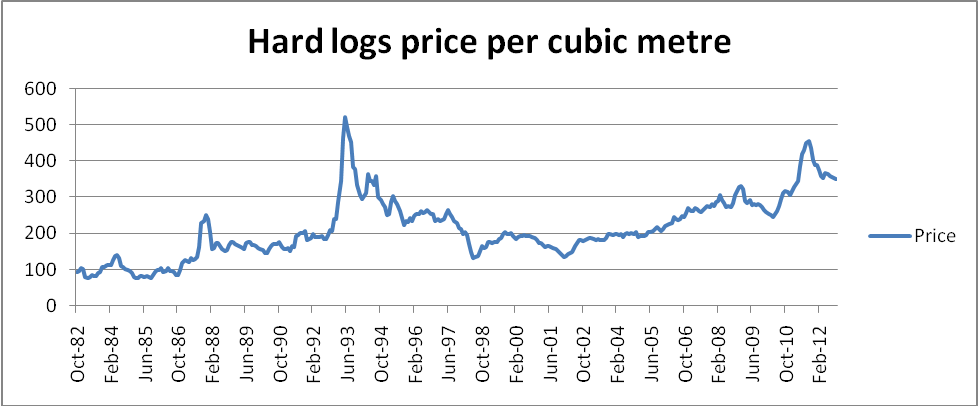

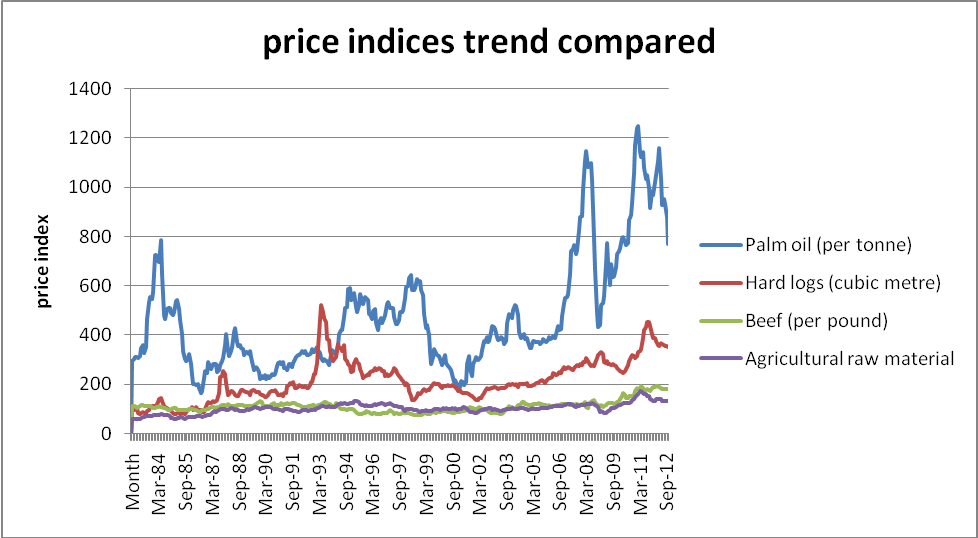

The price of timber is more volatile than the price of other products that use the same resources, such as beef and agricultural products. However, palm oil prices have been more volatile than the price of hardwood logs during the same period. The price of hard logs has been more stable in recent years than it was in the 1960s and 1970s. The stability may be caused by the existence of a more efficient global market for timber that regulates supply and demand.

The future of the Tasmanian forestry industry will be dependent on the investment made in plantations. Fast-growing species, such as Blackwood, provide alternatives for firms that seek to invest in hardwood plantations. More activism from environmentalists will ensure that reserved forests are not used for supply of timber. In the future, closure of inefficient processing facilities is likely to continue. They will be more investment in efficient processing facilities.

Background

Tasmania is an island in Australia located south of the mainland. The Tasmania forestry industry is supported by forests in wet areas and forests in dry areas. Public and private forests cover 49% of the land in Tasmania. Agricultural land and urban development cover 18% and 6%, respectively (FIAT, 2014). Reserves account for 47% of forest cover in Tasmania. The industry employs about 6,300 people and contributes about $1.4 to $1.6 billion annually to the Australian economy (FIAT, 2014).

Economic yields per hectare are above 500 tonnes (FIAT, 2014). Partial harvesting is the most common method of harvesting. Clearfelling accounts for 26% of both harvesting methods. Trees that reach a height of 85 metres are protected through a tall trees policy. Most of the forested land in Tasmania falls under the control of the government. Forestry Tasmania has been issued the right to manage 1.5 million hectares of forest land on behalf of the government (Forestry Tasmania, 2012, p. 4).

The Tasmania forestry industry experienced a decline in recent years. The decline is attributed to successful protests by environmentalists, closure of inefficient processing facilities, reduced competitiveness due to a strong Australian dollar, and the global financial crisis among other factors (Schirmer, 2010, p. 2). In the Tasmanian industry, employment opportunities increased by 7% between 2006 and 2008. However, it declined by 33% between 2008 and 2010 (Schirmer, 2010, p. 3). A number of businesses also declined from 514 to 464 between 2006 and 2008, and from 464 to 410 between 2008 and 2010 (Schirmer, 2010, p. 3).

The industry is more reliant on native forests than on forest plantations. In 2010, employment derived from native forests accounted for 55% of opportunities. Softwood and hardwood plantations accounted for 26% and 19% of employment in 2010 (Schirmer, 2010, p. 6). Native forests take a long period of time to maturity. The only hardwood of a native type considered for plantations is the Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon). It can mature at a period of 60 years (TWFF, 2004, p. 12). There is a set of species that are classified as non-commercial because of previous harvesting techniques that made their current quantities unviable.

The global forest industry characteristic is production-oriented. People purchase what is available on the market (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 5). The characteristic is changing to produce what people want. There is a global market where consumers are far away from the areas of production. Emerging economies have increased the demand for timber because of the improved purchasing power of the middle classes. There are well-developed import and export supply-chains. China is the main importer of hardwood timber.

The European Union is the main importer of wood pellets for the generation of power (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 7). Logging costs vary in different countries.. Logging costs are high and can exceed 70% of the total operating cost (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 172). The industry is characterized by low profitability. The return to capital employed (ROCE) between 1999 and 2008 was between 2.3% and 6.5%. Businesses have been setting targets to achieve a ROCE form 10% to 12% (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 6).

The low barriers to entry have enabled the industry to have a large number of small-scale producers. A large number of producers makes it difficult to control prices (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 6). Forests cover about 30% of the world’s land (Gustafsson andBaker et al., 2012, p. 633). Russia has the largest stock of high quality softwood. Timber products have substitutes and complements. The substitutes and complements may change according to emerging technologies. The retention harvesting approach may enable people to harvested timber from native forests without concerns of tampering with biodiversity (Gustafsson andBaker et al., 2012, p. 641).

In the formal sector, the forestry industry employs over 18 million people globally (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 3). When the formal and informal sectors are combined, the industry supports more than 50 million workers.

The global forestry industry is characterized by protests against harvesting of natural forests in many countries (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 212). Protests are also found in Australia. There have been protests against the establishment of a paper mill Tasmania. In Tasmania environmental activism has once called upon the boycott of products made from timber harvested in the wet eucalypt forests. Reserved Tasmanian forest occupies 50% of forested land as a result of environmental activism (Messier and Puettmann et al., 2013, p. 274). Both the private and public sectors are required to balance between revenues from harvested and the ecological needs of the surrounding areas (Gustafsson andBaker et al., 2012, p. 633).

Government policy

Tariffs

Impact of tariffs

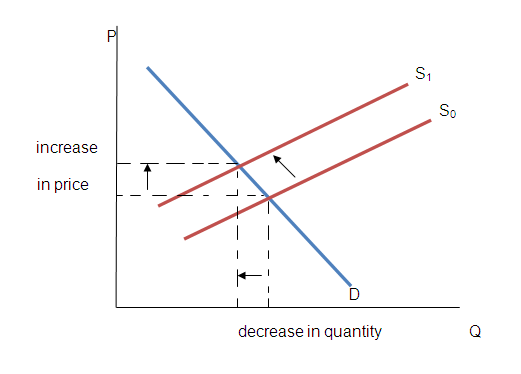

By imposing tariffs on non-Tasmanian timber products, there will be an increase in the price of products made from non-Tasmanian timber. Tasmanian timber products will be relatively cheaper increasing their demand. Graph 1 shows the impact of tariffs on the equilibrium quantity of non-Tasmanian timber products. The price of product increases and the equilibrium quantity reduces. The supply curve shifts to the left because less of the product is supplied. S1 represents the supply curve after tariffs have been imposed and S0 is the supply curve before tariffs are imposed.

The consumer will pay a higher price for the products. The consumer will demand less of the timber because of their reduced ability to purchase. They may seek substitutes that are cheaper than the non-Tasmanian timber products. The producers of non-Tasmanian products will sell less of their products in Australia when demand declines.

Different demand and supply curve characteristics

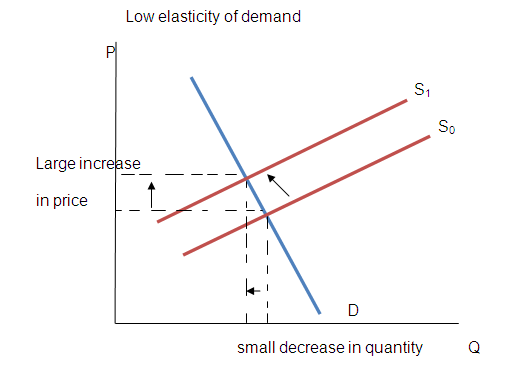

Low elasticity of demand occurs when Australians response to decline consumption is of a smaller proportion than the change in price. When there is a low elasticity of demand, the demand curve becomes steeper. A large increase in price results in a small change in price as shown in Graph 2 (Taylor and Weerapana, 2012, p. 364). There will be a small change in the quantity of imports.

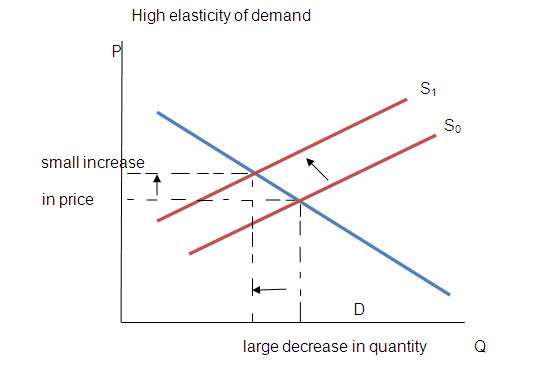

High elasticity of demand results in a large change in quantity demanded for a small change in price (Taylor and Weerapana, 2012, p. 364). As shown in Graph 3, there will be a large decrease in quantity of timber demanded if demand is highly elastic. Australians may reduce consumption of non-Tasmanian timber products by a small proportion under low elasticity of demand. They may increase consumption of Tasmanian timber products by a small proportion.

Graph 3 shows the changes that occur when the demand is highly elastic (Taylor and Weerapana, 2012, p. 364). A small change in price results in a large change in quantity demanded. When the demand is highly elastic, consumers will reduce the purchase of non-Tasmanian timber products by a large margin. In addition, they will increase the demand of Tasmanian timber products.

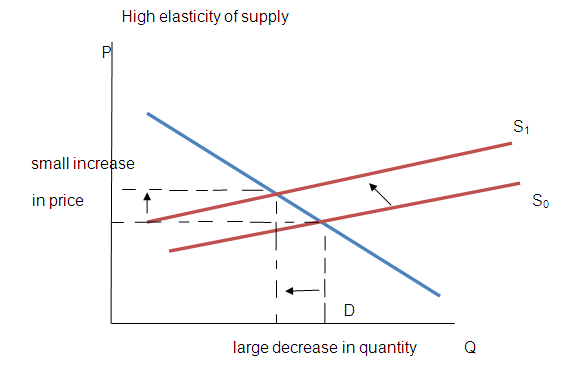

High elasticity of supply

High elasticity of supply occurs when production reduces by a large percentage for a relatively smaller percentage change in price of product (Taylor and Weerapana, 2012, p. 364). Graph 4 shows that equilibrium quantity reduces by a larger proportion for a small change in price.

Low elasticity of supply

Low elasticity of supply may cause Australians to continue purchasing non-Tasmanian timber products even after the government has imposed tariffs on imported timber products.

Views on the hypothetical decision

The global timber products may be considered to have a highly elastic demand. The presence of substitutes has its impact on increasing the elasticity of demand. Non-Tasmanian timber products can be substituted with Tasmanian timber products and non-wood products. Tariffs will be effective in increasing the use of timber from Tasmanian forests. The success of the policy is limited by a low inelastic supply. Producers of timber cannot increase the supply in the short run. If they increase supply more than the regulated amount, then a shortage may occur in the future that may force the government to reverse its policy.

Subsidies

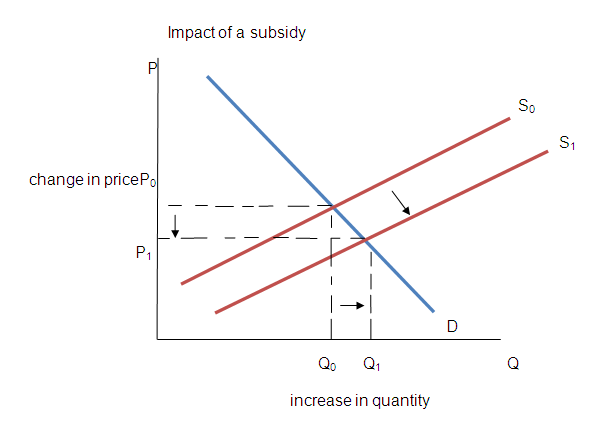

Impact of a subsidy

Subsidies issued to producers of Tasmania timber reduce the prices of products (see Graph 5). They also cause supply to increase when they are issued on a per-unit basis (Gwartney and Stroup et al., 2014, 87). The effectiveness of the policy will depend on the elasticity of supply and demand. Consumers are likely to benefit when the supply is highly elastic. The policy is ineffective when the supply is highly inelastic because demand will push prices up once they have been reduced (Gwartney and Stroup et al., 2014, 88). Producers will be the main beneficiaries of the policy that aims at increasing both production and consumption.

Different demand and supply characteristics

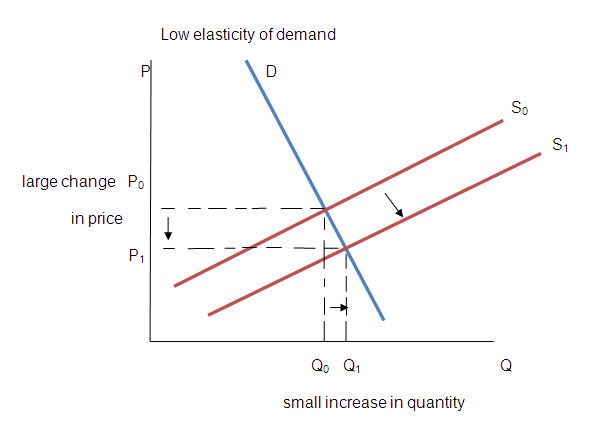

Low elasticity of demand

Low elasticity of demand shows that Australians will not respond to the fall in prices by a large proportion. Producers cannot increase production if consumers continue using the same level of consumption. It will lead to a small increase in the equilibrium quantity than expected for a proportionately large change in price (see Graph 6).

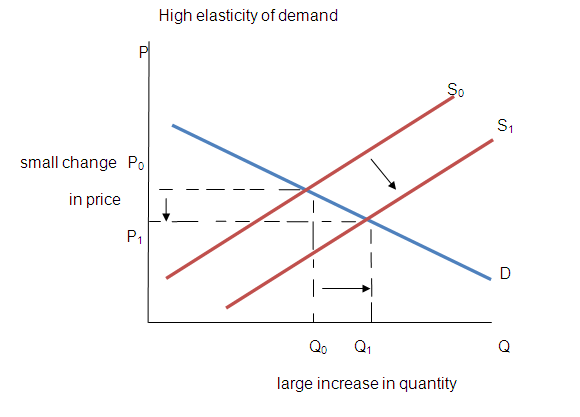

High elasticity of demand

High elasticity of demand would be the ideal condition together with a high elastic supply (Taylor and Weerapana, 2012, p. 369). The subsidy policy would give the expected results. There will be increased production and consumption. Customers respond, by a large margin, to the fall in prices as shown in Graph 7 below.

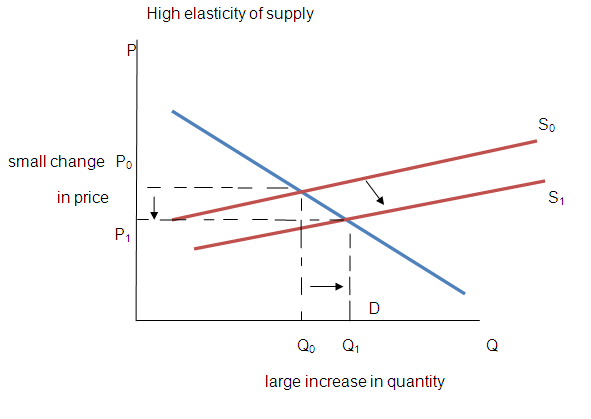

High elasticity of supply

High elasticity of supply should be the main target of a subsidy. It may function even when the domestic market is inelastic because the global demand is supported by an increase in demand from the emerging economies (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 7). If the government’s main target is to increase production for exports, a highly elastic supply will not rely completely on the elasticity of demand in the domestic market. High elasticity of supply results in a large change in equilibrium quantity for a small change in price (see Graph 8). The supply curves become less steep as a result of increased sensitivity to prices.

Low elasticity of supply

Low elasticity of supply will make the subsidy policy ineffective under all conditions. An attempt to set price ceiling that is not supported by increased supply will result in a black market for timber products.

Views on the hypothetical decision

The policy can be more effective when the supply for timber from Tasmanian unnatural forest is elastic. Increased production from natural forests is an unwanted effect because protest from environmentalists is likely to follow (Hansen and Panwar et al., 2014, p. 216). A high elastic demand and supply would make the policy more effective. The demand for timber may be elastic but the supply cannot be increased quickly in the short run without problems of shortage in the future. Subsidy may not appear as a better option because local timber supply has low elastic.

Market Trends

Plotting timber sales

The total timber consumption has increased continuously since the 1960s. The increase in consumption is driven by increase in population because the apparent consumption per person has declined. The consumption of timber from broadleaved trees has remained fairly constant. The reason could be that broadleaved trees are in most cases hardwood that are harvested from natural forest. There are policies that prevent harvesting from natural forests. Consumption of timber from coniferous trees has taken a trend similar to the increase in population. The volume of exports has overtaken the size of imports since the mid 1990s.

Sales volume

Kt is bone dry tonnes ‘000m3 is thousands of cubic metres

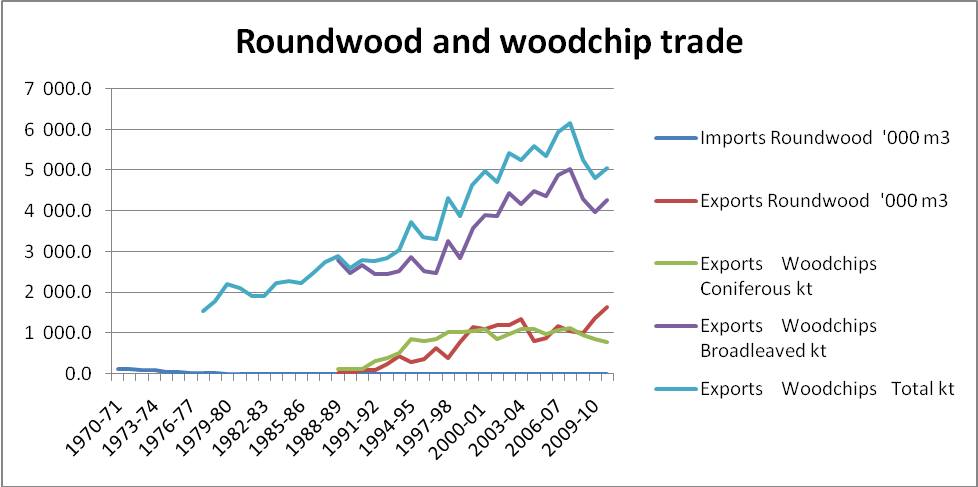

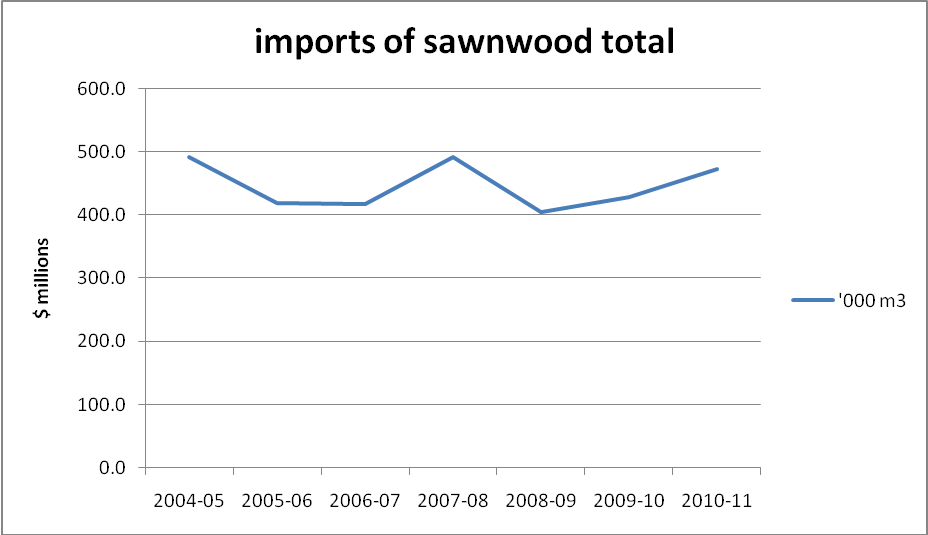

As shown in Graph 10, the roundwood and woodchip trade has increased the volume of exports. Import of roundwood has declined. In the recent years, the export of woodchip has declined for both broadleaved and coniferous types. Timber that was initially exported as woodchip is now processed for veneer (Forestry Tasmania, 2012, p. 6). Ta Ann Tasmania is an enterprise that has been licensed to process timber that was initially exported as wood chip into veneer. It has built more efficient processing plants. Ta Ann has invested over AUD 78.9 million in the business and contributed AUD 45 million to the Tasmanian economy in 2012 (Forestry Tasmania, 2012, p. 6). Graph 11 below shows that the imports of sawnwood has declined.

Plotting timber prices

The price of timber is more volatile than the price of other products that use the same resources such as beef and agricultural products. However, palm oil prices have been more volatile than the price of hardwood logs during the same period. Palm oil and timber prices may appear more volatile because of the size of product under consideration. One tonne of oil and one cubic metre of timber are expected to have large price variation than a pound of beef.

However, the trend shows that other two products prices have remained fairly constant. The recent increases have occurred in other products as well. The percentage change eliminates the impact of size of product under consideration as it can be seen in Graph 14. It shows that the price of hard logs has been more stable in recent years than it was in the 1960s and 1970s. The stability may be caused by the existence of a more efficient global market for timber that regulates supply and demand.

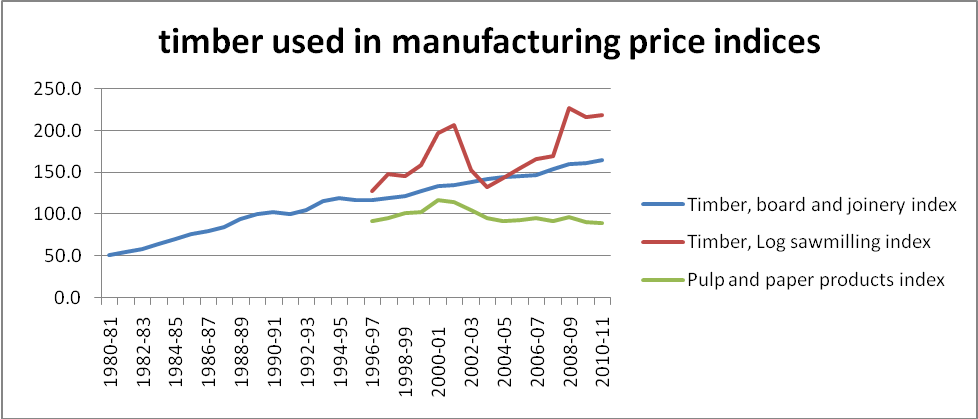

Timber as a raw material

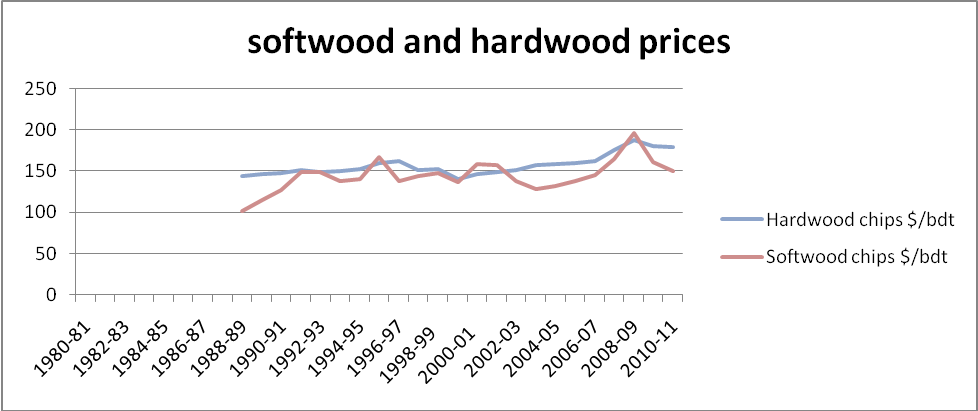

Softwood and hardwood prices

Hardwood and softwood chips prices have remained fairly constant before 2000 and have declined in recent years. The decline in the period after 2008-2009 can be attributed to the global financial crises that resulted in reduced consumption of many products.

Future industry prospects

The future of the Tasmanian forest industry will be dependent on investment in plantations. The industry has declined in recent years because of low profitability in the industry. Low profitability has been blamed on the low re-investment levels in the industry. The current industry is more reliant on native forests. The global demand for hardwood logs will push the firms managing forests to seek alternatives to timber from native forests. Fast-growing species, such as Blackwood, provide alternatives for firms that seek to invest in hardwood plantations. Investors will use plantations to increase the supply of fast-growing hardwood and softwood. However, the impact of their investment can only be felt in the long run.

Successful activism from environmentalist will ensure that reserved forests are not used for supply of timber. The need to create a balance between profits and ecological benefits will intensify. Environmentalists are raising concerns over plantations that use a single species over a large area.

One of the concerns raised is the potential for an outbreak of plant disease or pests as a result of a single tree species covering a large surface (Messier and Puettmann et al., 2013, p. 281). Activism may also expand to restrict imports from countries that do not have clear environmental conservation policies. Policies tend to prioritize efficiency before equity. Environmental activism has stepped in to create a balance.

The global market has brought more concerns for competitiveness. Tasmania relies more on forestry than other regions in Australia. In Tasmania, the need for competitiveness has seen the closure of three major processing facilities between 2008 and 2010. It resulted in the loss of 760 job positions (Schirmer, 2010, p. 3). Ta Ann Tasmania is an example of new more efficient facilities that can compete globally in processing timber for veneer production. In the future, closure of inefficient processing facilities is likely to continue. They will be more investment towards efficient facilities. More job positions may be lost during the transition period.

The upward export trend is likely to continue as wet eucalypt forests provide fast-growing forests alternatives. A strong Australian dollar remains a challenge to competitiveness. Imports will decline as more efficient processes are incorporated in the forestry industry. Exports may target the emerging markets that have experienced a great increase in purchasing power in recent years. The country will meet competition from high quality softwood from countries such as Russia where softwood forests grow at a slow rate.

Conclusion

The Tasmanian forestry industry is shifting towards efficiency in processing timber to enhance competitiveness in the global market. The effectiveness of a subsidy or tariffs policy depends on the elasticity of supply and demand. Low elasticity of supply will make both policies ineffective. High elasticity of supply becomes effective even when demand in the local market is inelastic because the global demand is elastic.

Emerging markets offers an opportunity for a highly elastic supply. Tariffs may be used to protect the domestic industry from cheaper timber imports. If the global supply has low elasticity, tariffs may not reduce the supply of timber into Australia or Tasmania. Producers will compensate for the tariffs by reducing prices or costs. Subsidies withdraw resources from alternative uses when tariffs raise funds for the government. As a result, the government may be more inclined to use tariffs than subsidies.

Another reason that could make the government choose tariffs is the inelasticity of supply. When the supply is inelastic, producers reap most of the benefits of subsidies without passing over the benefits to consumers. In recent years, the price of timber has become more stable as a result of a global market mechanism. Processing is shifting to more efficient techniques. Tasmanians have witnessed the closure of processing facilities that were considered inefficient in an attempt to increase competitiveness in the global market.

Reference List

ABARES. 2014. Forestry. Canberra: ABARES.

FIAT. 2014. Statistics. [online]. Web.

Forestry Tasmania, 2012. Forest management in Tasmania: the truth. [pdf] Tasmania: pp. 4-6. Web.

Gustafsson, L., Baker, S., Bauhus, J., Beese, W., Brodie, A., Kouki, J., Lindermayer, D., Lohmus, A., Pastur, G., Messier, C., Neyland, M., Palik, B., Sverdrup-Thygeson, A., Volney, J. Wayne, A. and Franklin, J., 2012. Retention forestry to maintain multifunctional forests: a world perspective. BioScience, 62 (7), pp. 633-641.

Gwartney, J., Stroup, R., Sobel, R. and Macpherson, D. 2014. Economics: Private and public choice. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, pp 87-88.

Hansen, E., Panwar, R. and Vlosky, R. 2014. The global forest sector: changes, practices, and prospects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 3-9, 172-216.

Messier, C., Puettmann, K. and Coates, D. Managing forests as complex adaptive systems: building resilience to the challenge of global change. New York, NY: Routledge.

Schirmer, J. 2010. Tasmania’s forest industry: trends in forest industry employment and turnover 2006 to 2010. [pdf] Hobart Tasmania: pp. 2-6. Web.

Taylor, J. and Weerapana, A. 2012. Principles of economics. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning, pp. 364-366.

TWFF, 2004. Tasmania’s specialty timber industry: a blue print for future sustainability. Kingston Tasmania: p. 12. Web.