My favorite taxon is rhinoceros. Modern rhinos, represented by a one-horned Indian rhinoceros with a pointed upper lip and a two-horned African rhino with a wide rectangular mouth, are pitiful remnants of a rich in species group of mammals. Many skeletons, bones, and teeth left from their predecessors in the Tertiary and Quaternary deposits. Central Asia is considered to be the place of rhinos’ origin because a lot of remains of the most ancient representatives were found there. The remains of various rhinos were found in the steppes and deserts of Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

Among the living land mammals, rhinos are the third largest in size behind elephants and hippos. Modern rhinos have three toes on each foot. Despite their large size and short legs, these animals are able to run quickly over short distances; for example, the black rhino reaches speeds of up to 50 km/h. The color of skin depends on the soil and the silt and dust, where an animal lies: his originally lead-gray skin becomes in some cases white, in others – reddish, and in areas covered with lava – completely black. The skin of the rhinoceros is completely devoid of vegetation, except for the tip of the tail and the edge of the ears. He also has no sweat glands, hence the addiction of these animals to cooling mud baths.

The state of the populations of the two most ancient species of this family, the Javanese and Sumatran rhinos, is appalling. At any moment they can be exterminated by poachers who hunt rhinoceroses because of their horns. The entire family of rhinos is extremely vulnerable, but African species are in the focus of attention of conservationists, the Indian one is still quite stable in numbers, but the Javanese and Sumatran ones are almost exterminated.

On the grey market, rhino horns are very expensive due to some kind of superstition: in East Asian pharmacies, dried rhino horns are sold as a remedy for impotence. Recently, a thorough scientific study of the healing properties of the horn was carried out, which showed that it does not have any healing properties. However, the demand does not stop, and many species of animals have been exterminated as victims of harmful beliefs.

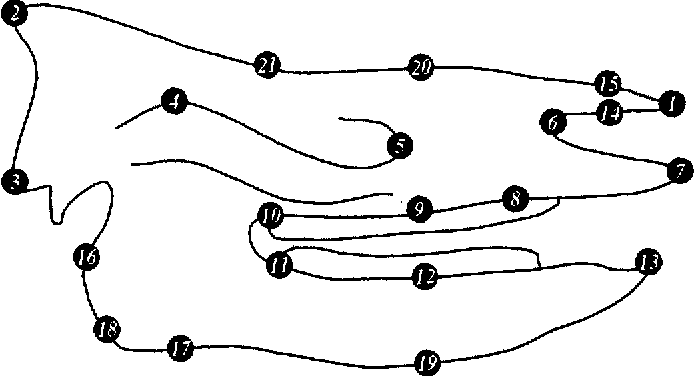

For the study two articles have been chosen; the first, Skull evolution in the rhinocerotidae (Mammalia, Perissodactyla): Cartesian transformations and functional interpretations, was written by G. S. Bales in 1996 and discusses skull evolution in rhinocerotidae (See Figure 1). The second one is Earliest known unequivocal rhinocerotoid sheds new light on the origin of Giant Rhinos and phylogeny of early rhinocerotoids was written by H. Wang et al. in 2016. The article informs readers about the earliest findings in the area of phylogeny of early rhinos.

In ancient Tertiary times, many rhinos were small and hornless, slender and more agile than their descendants. The rest of the features of their skeleton and teeth show that they were rhinos. However, along with small primitive rhinos in Asia, giant rhinos were found. They also had primitive features in structure, were hornless, but exceeded large elephants in size (Bales, 1996). In Kazakhstan, in 1912, such a giant rhinoceros was first found in Oligocene deposits and was called Indricotherium. It reached five meters in height and was, apparently, the largest animal known on land.

It had a massive body and thick columnar legs, similar to an elephant. A skeleton of Indricotherium is exhibited in the Paleontological Museum of the Academy of Sciences. In recent years, the remnants of Indricotherium and other giant rhinos were found in many areas of Central Asia and even in the Caucasus.

Note. Reprinted from Skull evolution in the rhinocerotidae (Mammalia, Perissodactyla): Cartesian transformations and functional interpretation (p. 270) by G. S. Bales, 1996, Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 3(3), 261–279.

The remains of rhinos in Tertiary deposits are numerous and belong to different forms. The first horned rhinos, similar to modern ones, appeared in the Miocene era. Many extinct rhinos had two horns – one behind the other, similar to the modern African rhino. The base of a horn is a bony cone on the nasal bones of the skull; the horn of rhinos is fibrous. At the beginning of the Anthropogen, there lived such peculiar rhinos as Elasmotherium, with a large horn, planted on a huge bump on the forehead, not on the nose. Until recently, a contemporary of the mammoth, two-horned hairy rhinoceros, lived in the north of Europe and Asia.

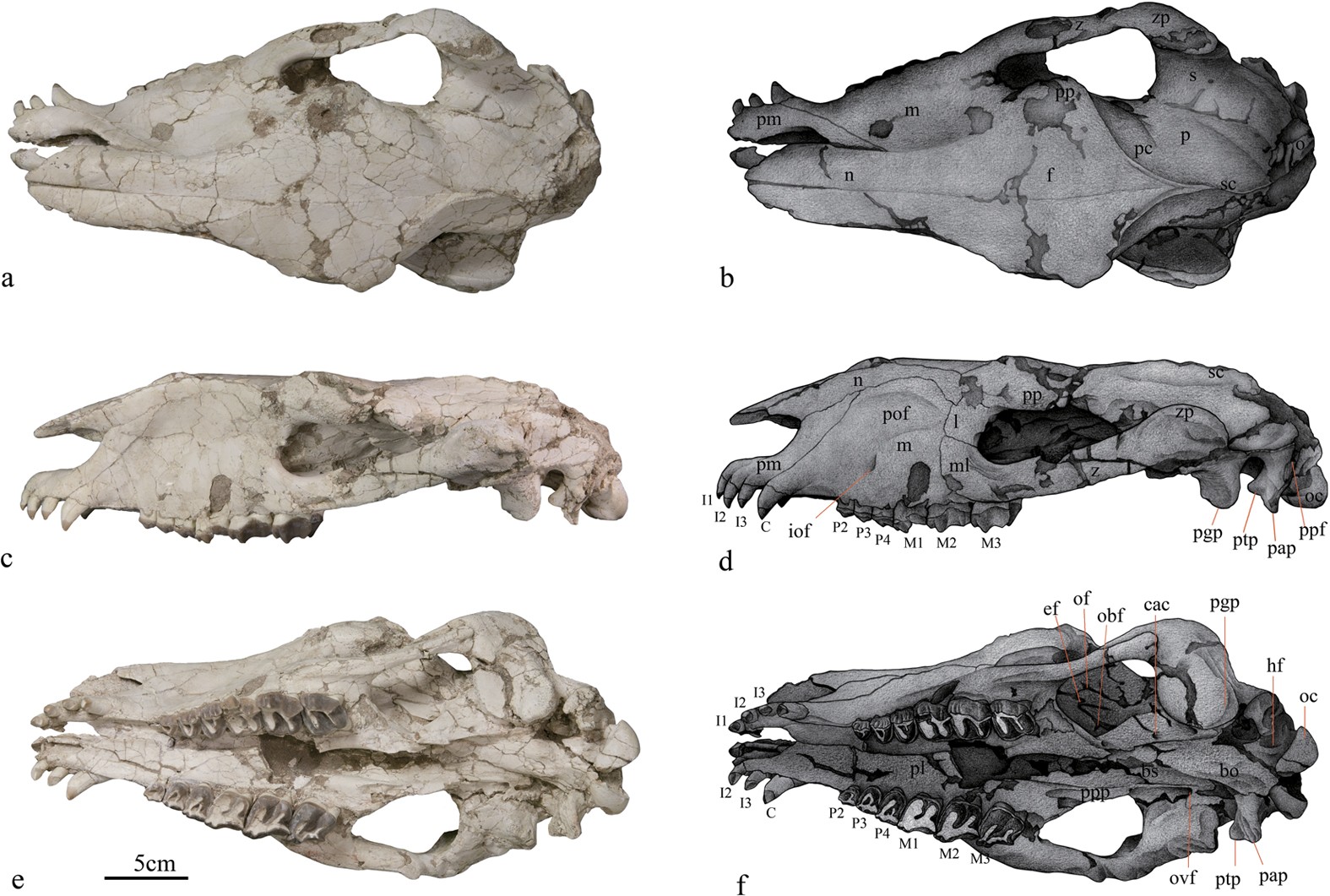

The second article under consideration was written in 2016, and the research tells about phylogeny of rhinos. The latter are a group of primitive rhinoceroses with a relatively large body in the Eocene, which are generally considered to be close relatives of giant rhinos (Wang et al., 2016). The article informs about a new forstercooperin, Pappaceras meiomenus sp. nov., from the Late Eocene Arshantinskaya Formation, Erlyanskaya depression, Neimongol, China. The scientists thoroughly investigated the skull of rhino and came up with the process of skull formation (See Figure 2).

Note. Reprinted from Earliest known unequivocal rhinocerotoid sheds new light on the origin of Giant Rhinos and phylogeny of early rhinocerotoids (p. 26) by H. Wang et al, 2016, Scientific Reports, 6(1).

Thus, the first article provides general investigation of changes in shape of rhinos’ skulls. The second article shows the earliest evidence of reduction of the first upper premolar intrhinos and in the main features of the skull resembles the juxia paraceratery (Wang et al., 2016). It confirms the interpretation that the treasures of forstercooperiins are the ancestors of paraceraterines.

References

Bales, G. S. (1996). Skull evolution in the rhinocerotidae (Mammalia, Perissodactyla): Cartesian transformations and functional interpretations. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 3(3), 261–279.

Wang, H., Bai, B., Meng, J., & Wang, Y. (2016). Earliest known unequivocal rhinocerotoid sheds new light on the origin of Giant Rhinos and phylogeny of early rhinocerotoids. Scientific Reports, 6(1).