Abstract

Online shopping becomes increasingly important for modern businesses, and there is a lack of research on the topic, which is why the present dissertation is dedicated to an analysis of the relationships between online shopping applications and impulse buying. To investigate the two phenomena, a mixed-methods study was designed. One thousand thirty shoppers were surveyed, and 20 people were interviewed.

In addition, 74 buyers who used exclusively online shopping applications or brick-and-mortar stores completed a survey which was employed to determine if any of the two groups were more likely to engage in impulse buying. A statistical analysis of this survey demonstrated that while online shoppers did seem to buy spontaneously more often, the difference was not statistically significant.

The analysis of the rest of the responses (both surveys and interviews) shows that for the time being, it is impossible to state if there is a relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying, but online shopping applications have multiple opportunities for promoting the behaviour. In conclusion, the dissertation offers recommendations regarding the use of said opportunities.

Introduction

Nowadays, online shopping becomes increasingly important, which makes it a useful tool for modern businesses. In addition, the research on the topic is becoming more diverse as it explores the various aspects of online purchases. However, since online shopping is a relatively recent development, the research does not cover all its significant features (Badgaiyan & Verma 2014; Rezaei et al. 2016). One of the topics that are not studied very extensively is the relationship between online shopping applications and impulsive buying behaviour.

Impulsive buying behaviour or impulse buying can be identified as unplanned or spontaneous buying. It is a very important factor to consider for modern businesses, mostly because it is responsible for a large percentage of sales worldwide (Lin & Lo 2015; Thompson & Prendergast 2015). Impulse buying in online shops is not very extensively studied (Park, Jun & Lee 2015), but due to the development of online shopping applications, this topic becomes more and more important. As a result, the present dissertation aims to investigate it and contribute some data that can be used by modern businesses.

The research has several key objectives, which can be summarised as follows.

Objectives

- First, the dissertation aims to determine if there is any relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying.

- Further, it intends to investigate this relationship. Specifically, a discussion of the possible reasons and outcomes of this relationship, as well as its implications for businesses, is planned.

- Eventually, the study intends to provide some advice that would guide the use of online applications for stimulating impulse buying.

These objectives can be transformed into the following research questions.

- Is there a relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying?

- If they can be found or theorised, what are the possible reasons for this relationship?

- What effects could this relationship have? Specifically, in which ways could shopping applications affect impulse buying?

- What are the implications of the findings for businesses? Can any advice on the matter be provided?

Thus, the study was developed with the general aim of offering modern businesses some information on impulse buying that can be employed in practice. This dissertation will contribute some data to the research of impulse buying behaviours and investigate the possible relationships between online shopping implications and impulse buying. As a result, the study should have both theoretical and practical value which is explained by the importance of the chosen topics and their underrepresentation in recent research.

The rest of the dissertation will be structured as follows. First, a literature review on the topics of impulse buying and online shopping applications will be presented; offline (brick-and-mortar) stores will also be considered as a counterpoint to online ones. Further, the methodology of the study that was developed for this dissertation will be described, including the methods used, the sample recruited, and the ethical considerations reviewed. Then, the findings of the study will be presented, and their discussion will be carried out in the following chapter. Eventually, conclusions will be made regarding the coverage of the research questions, and recommendations will be offered.

Background and Literature Review

Impulse Buying Behaviour: The Terminology

Impulse buying behaviour has received some attention from modern researchers, including psychologists (Thompson & Prendergast 2015). However, it is also of importance to marketing and business research, and the specialists in these fields have dedicated some attention to the phenomenon as well (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017). Simply put, impulse buying is characterised by being spontaneous; it is the buying that occurs without planning, and its antonym is rational, planned buying (Lin & Lo 2015).

It is important to differentiate impulse buying and compulsive buying; the former is a norm, a simple situation in which a person acquires things without planning. The latter is a disorder that is characterised by negative outcomes, causes severe distress and requires medical attention (Darrat, Darrat & Amyx 2016; Thompson & Prendergast 2015). This form of spontaneous buying is not the topic of the present research; most often, it is studied to develop interventions that can help compulsive buyers to resolve their problem.

Impulse buying, on the other hand, is not harmful to buyers, although it might cause regret in certain instances (Lee, Park & Jun 2014). Still, it has been defined as “a behaviour resulting from the positive effect that a consumer spontaneously experiences when confronted with a product or service” which is manifested in the wish to buy a thing spontaneously and instantly (Lin & Lo 2015, p. 39). In addition, it is very common; according to different studies, up to 90% of the population purchase things impulsively from time to time (Lin & Lo 2015; Thompson & Prendergast 2015).

Impulse buying is believed to be responsible for up to 50% of all sales in the world (Lin & Lo 2015), and 40% of online purchases are also estimated to be spontaneous (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017; Chen & Yao 2018). In other words, impulse buying is significant for businesses, which is why stimulating it is rational. This fact explains the interest of the present dissertation on the topic: any factors that can potentially improve impulse buying are of importance to business research.

There are different types of impulse buying; at least four different forms of it have been identified in the literature on the topic (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017). Pure impulse buying is a simple unplanned purchase that occurs accidentally. Reminder impulse buying happens when a person sees a product and is reminded of the fact that they need it.

This type of impulse buying is especially common with the things that are used regularly (for instance, food or drinks); if a person does not remember to buy such a thing before seeing the product, reminder impulse buying occurs. Suggestion impulse buying happens when a person encounters a brand-new product and decides that he or she needs or wants it. In addition, there are planned impulse buying; it happens when a person goes to a store with the plan of buying something unplanned (Bellini, Cardinali & Grandi 2017; Chen & Wang 2015; Zhang et al. 2018). In the present dissertation, the term “impulse buying” incorporates all these options.

Different approaches to explaining impulse buying have been developed. However, one of them is particularly common in business research: Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R or SOR) (Chen & Yao 2018; Ju & Ahn 2016; Lin & Lo 2015; Parboteeah, Taylor & Barber 2016; Prashar, Vijay & Parsad 2017; Wu & Li 2018). SOR is a framework that explains impulse buying by considering the stimuli that can cause it, the organism or the person who processes the stimuli, and the response to the stimuli (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017; Parboteeah, Taylor & Barber 2016).

The response element incorporates the reaction to the stimulus and its evaluation (that is, they wish to buy a product) and the action of impulse buying (Parboteeah, Taylor & Barber 2016). This framework incorporates both the individual and environmental factors that can influence impulse buying, which is especially helpful for this study since it is dedicated to investigating the relationship between impulse buying and the stimuli of online shopping applications.

The research on impulse buying is expanding and becoming more extensive, but there is still much to investigate. Some findings require checking, and some topics related to impulse buying have not been explored to the full extent (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017; Thompson & Prendergast 2015). For instance, online impulse buying has not been studied very extensively (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017; Chen, Su & Widjaja 2016). Given the fact that online shopping applications, as well as online marketing, are also not very well researched (Badgaiyan & Verma 2014; Rezaei et al. 2016), it becomes apparent that the consideration of impulse buying behaviour in online shopping applications and their comparison to offline stores may be very helpful. Thus, the present dissertation aims to cover a gap in modern research.

Factors Impacting Impulse Buying Behaviour

Given the pervasiveness of impulse buying, business studies look into the ways of promoting impulse buying, determining the factors which cause it and can be used by businesses. In SOR, the stimulus element incorporates the factors that can potentially trigger impulse buying (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017). However, the studied behaviour is rather complex, which brings attention to the second element of the framework: the organism which signifies the person who can be engaged in impulse buying (Lee 2018).

Here, it should be pointed out that impulsivity is closely connected to psychological factors, which explains many of its predictors (Chen & Wang 2015; Husnain & Akhtar 2016; Lin & Lo 2015; Ozer & Gultekin 2015). Certain theorists argue that the actual cause of impulse buying consists of varying problems with self-regulation, which is especially prominent in compulsive buying (Thompson & Prendergast 2015). Therefore, individual factors are important to consider.

As shown by Thompson and Prendergast (2015) and Chung, Song and Lee (2017), the currently existing evidence suggests that certain character traits or skills can predict impulse buying. In fact, some people are believed to have an impulse buying tendency, which is defined as a particular proneness to buying impulsively (Badgaiyan, Verma & Dixit 2016). If the lack of self-regulation is the cause of impulse buying, the people who are worse at self-regulation are more prone to impulsive, spontaneous purchases and vice versa.

Self-regulation is generally comprised of skills and abilities like setting goals, monitoring oneself, and restraining one’s impulses (Badgaiyan, Verma & Dixit 2016; Thompson & Prendergast 2015). Using this information, Thompson and Prendergast (2015) demonstrate that certain traits like neuroticism or extraversion can affect one’s impulse buying.

The same study also indicates that a person’s state of mind may contribute to impulse buying, and Ozer and Gultekin (2015) support the idea through their investigation of pre-purchase moods. Similarly, according to a study by Park, Jun and Lee (2015), the shoppers who feel “smart” (that is, feel that they can use mobile shopping to buy things cheaper) are more likely to buy impulsively.

Furthermore, the specific buying preferences and habits of a person may matter. For example, the people who shop in a particular store regularly are more likely to buy from it impulsively (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015). On the other hand, people who prefer to plan their purchases are less likely to buy impulsively; extensive pre-planning is associated with lower impulse buying rates (Bellini, Cardinali & Grandi 2017).

Finally, there are certain tendencies found in different groups of buyers. Thus, women and men tend to make impulsive purchases of different products as associated with their social roles, and younger people are more likely to buy spontaneously than older ones (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015). Overall, the personal traits, characteristics, moods and feelings of a shopper matter when impulse buying is concerned.

In addition to personal characteristics, other phenomena that promote or constrain impulse buying may be significant. Socio-cultural factors have been shown to have some importance; they can include the influence of other people like one’s family or peers, the specifics of one’s culture and subculture, as well as one’s socioeconomic position (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015; Islam et al. 2018).

Further, the situation of purchase is noteworthy; aspects like the time of shopping or the amount of money available may be significant (Parboteeah, Taylor & Barber 2016). For example, according to Akram et al. (2018) and Bhuvaneswari and Krishnan (2015), credit cards promote impulse buying due to the opportunity of spending more money, and if a person has much time for browsing the goods, they are more likely to buy something impulsively.

In other words, some factors that cause impulse buying are either individual or situation-specific, which is why they are unlikely to be influenced by businesses. However, the literature on the topic also demonstrates that there are external stimuli, which can and have been used by stores to cause customers to buy impulsively. The strategies that are commonly used by both online and brick-and-mortar stores include discounts, special offers and limited-time offers (Lin & Lo 2015).

Further, the price of goods and quality of services is a factor (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015; Lin & Lo 2015). Recommendations are important, as well as advertising; all these stimuli can promote impulse buying (Bues et al. 2017; Lin & Lo 2015; Zhang et al. 2018; Wu & Lee 2015). Overall, different marketing approaches have an impact on impulse buying.

The product itself, as well as its presentation, can be significant. Specifically, its package, brand, visual appearance and guarantees associated with it (for instance, the possibility of a refund) can promote impulse buying (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015; Husnain & Akhtar 2016; Siahpush et al. 2015; Wu & Lee 2015). Moreover, seeing something new can become a factor; a new product may result in its spontaneous buying as shown by suggestion impulse buying (Bellini, Cardinali & Grandi 2017; Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017).

However, it is important to remember that all the above-described strategies affect different people in various ways depending on their preferences, worldviews and other factors that are united by the organism element of SOR (Parboteeah, Taylor & Barber 2016; Zhang et al. 2018). The specific strategies employed by online and offline stores will be discussed below.

In conclusion to this section, it should be mentioned that different types of shopping may be associated with different frequencies of impulse buying. For example, some evidence suggests that Internet buyers are more likely to buy impulsively when compared to those frequenting retail stores (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017; Lin & Lo 2015). Also, Lee, Park and Jun (2014) and Park, Jun and Lee (2015) note that there is a tendency for increased impulse buying among online buyers, specifically those who use mobile phones. Thus, it is possible that the differences in online and offline strategies or opportunities for promoting impulse behaviour may potentially result in one of the two being more conducive to spontaneous purchases.

Offline Stores Affecting Impulse Buying Behaviour

In this dissertation, online shopping applications are compared to brick-and-mortar stores. In this paper, they are going to be termed as offline stores to highlight the fact that they are different from online ones. This comparison is introduced because it is relatively simple to contrast online and offline means of shopping. In addition, online methods of shopping are relatively new and still developing (Badgaiyan & Verma 2014; Rezaei et al. 2016), which is why comparing them to the more traditional methods may be helpful. As a result, in this section, the methods of affecting impulse buying in offline stores will be considered to compare them to those available for online shopping applications.

The general strategies that are described above, including various pricing policies, advertisements, and the product itself are applicable to offline stores. However, researchers point out that brick-and-mortar stores have a very important advantage when prompting impulse buying: their buyers are physically present in the store, which provides multiple opportunities for enhancing their buying experience (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015; Su & Lu 2018).

Lin and Lo (2015) comment on the way different senses of buyers can be affected: a store can be decorated and scented, and music can also be used. In addition, the layout and displays of goods can be made appealing and supportive of cross-selling, which cannot be achieved in online stores (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015).

The environment of a store is very important for impulse buying; sensory stimulation, especially overstimulation, can suppress one’s self-regulation (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015; Lin & Lo 2015; Su & Lu 2018). The ability to touch a product was also described as helpful in promoting spontaneous purchases (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015). All these factors are not an option for online applications.

The location of a store can also be significant for impulse buying as one of the situational factors of a purchase. In other words, a convenient location makes a person more likely to enter a shop, browse the goods and decide to make a purchase. In addition, it should be noted that the use of technology in offline stores can be helpful; for example, it may be employed to facilitate transactions or provide entertainment (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015). Finally, the suggestions of salespeople can result in spontaneous buying (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015). To summarise, there is a number of impulse buying promotion strategies that are available for offline stores.

Online Stores Affecting Impulse Buying Behaviour

Having reviewed the methods employed by offline stores to promote impulse buying, it is necessary to consider online stores and their ability to achieve the same outcome. Here, it should be mentioned that online shopping applications do not receive much coverage in recent research.

However, mobile shopping, which includes shopping applications and e-commerce, which is a more general term, are sufficiently represented. In fact, there is some research dedicated to the comparison of online and offline stores and impulse buying in them, but it does not specifically focus on shopping applications (Bhuvaneswari & Krishnan 2015). Still, this information is mostly applicable and will be used for this section.

In general, the above-presented marketing approaches to impulse buying promotion are applicable to online shopping. In other words, factors like advertising or limited-time offers are important stimuli for online applications (Bues et al. 2017). However, several online-specific concerns should be reviewed. According to recent literature, the design of applications and websites appears to be of utmost importance.

For example, there is some evidence which indicates that the quality of the website and its ease of use (especially navigation) can contribute to impulse buying (Akram et al. 2018; Chen, Su & Widjaja 2016; Lin & Lo 2015; Rezaei et al. 2016; Turkyilmaz, Erdem & Uslu 2015; Wu, Chen & Chiu 2016). Perceived convenience, as well as control, in working with an online shop has been proven to have an impact on impulse buying (Lee, Park & Jun 2014), and this outcome can be achieved through careful design of an application.

Thus, as pointed out by Lin and Lo (2015), since online stores are unlikely to be able to affect any sense other than the visual one, it is particularly important to develop a pleasing website design with the help of pictures, colour, and fonts. The more vividly and interactively a product is presented, the greater the possibility of impulse buying becomes (Vonkeman, Verhagen & Dolen 2017). In summary, the visuals of online applications are a major tool in fostering impulse buying.

The quality of the information provided by a site is also important. It needs to be relevant, easy to understand, useful and complete (Chen, Su & Widjaja 2016; Lee 2018). Recommendation features should be considered, as well.

For instance, a study that was dedicated to Facebook and carried out by Chen, Su and Widjaja (2016) demonstrated that “Likes” may affect impulse buying. This finding can be extended to other forms of approval and recommendation since the latter tend to boost spontaneous purchasing as well (Husnain et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2018). Other examples can include the opportunity to write reviews of bought products and rate them; also, the electronic word-of-mouth is an important stimulus.

While offline shops have the opportunity to modify their environment, online shops also have a feature that can potentially improve impulse buying. In particular, online stores are more convenient: online buyers do not spend any time to get to the shop, and they can make a purchase at any time of day and night, although, admittedly, the delivery will consume some time (Chan, Cheung & Lee 2017). Given that prolonged browsing results in increased chases of impulse buying (Zhang et al. 2018), this advantage is very important.

On the other hand, the literature suggests that in some instances, online stores can benefit from mimicking offline ones. For instance, Ju and Ahn (2016) and Xiang et al. (2016) demonstrate the fact that social commerce sites can become similar to offline stores due to social presence, which enables the feeling of shopping together that is beneficial for improved experience and impulse buying. Also, Ju and Ahn (2016) note that music can be used in online stores; this way, they will be able to affect more than just the visual sense of a buyer. To summarise, despite the lack of some opportunities that are available to offline stores, online ones have their own advantages.

Methodology

During the process of designing the study, the research questions were used as a guide for determining the methods that could potentially achieve the aims of this dissertation. Given the fact that the research was intended to both determine a relationship and investigate it, it was apparent that a mixed-methods approach would fit it best. The following sections will present the different aspects of the research and explain their connection to the research questions of this dissertation.

Research Paradigm

When establishing a research paradigm for the dissertation, a perspective that would be applicable to the study’s aims was found. A critical realism paradigm is an approach that incorporates the general ideas of both positivism and constructionism, allowing for a middle-ground point between the two (Eriksson & Kovalainen 2016). According to positivism, objective reality does exist, and it can be both observed and measured, which fits this study’s aim of investigating the relationship between online shopping and impulse buying.

However, positivism does not account for the subjective aspects of observation, which makes this approach rather one-sided. On the other hand, constructionism recognises the significance of the subjective perspective of humans and points out the fact that knowledge is socially constructed, which highlights the impact that subjectivity can have on our perceptions.

Critical realism unites the two ideas and postulates both the existence of objective reality and the impact that the social construction of reality has on human knowledge. The convenience of this middle-ground perspective is pointed out by Eriksson and Kovalainen (2016): the authors note that due to its duality, critical realism can support and guide mixed methods designs. As a result, the present dissertation uses this approach, and it will be applied to the methods described below.

A Summary of the Methodology: Data Collection, Sample and Analysis

The methods employed in this dissertation included surveys and interviews. The former was used to test the presence of a relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying and to gather more data about the way impulse buying is influenced by online and offline shopping experiences. The latter were mostly used to explore the studied phenomena. The surveys were developed with the help of the Survey Monkey service, and the interviews were carried out in person with the interviewees determining the settings of the meetings.

Data analysis employed methods that fit the data studied. Thus, quantitative data were processed using statistical analyses, and qualitative data presupposed thematic analysis (Creswell & Creswell 2017; Hair et al. 2015; Heeringa, West & Berglund 2017). Specifically, to summarise the majority of the findings of the survey, the descriptive statistics produced by the Survey Monkey were included in the research.

However, the analysis of the first part of the survey required establishing the relationship between the two variables, which is why, for this task, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Due to the specifics of the sample (which was rather small) and data (which was not normally distributed), as well as the goal of the analysis (which consisted of determining if there was a relationship between the two variables), the choice of the test was justified (Momeni, Pincus & Libien 2017). This part of the analysis used SPSS. In addition, some of the graphs were created with the help of MS Excel.

Recruitment methods can be defined as quota and convenience sampling. The recruitment was done using online methods: Survey Monkey and social media were employed to invite people to participate in the surveys. The researcher also visited some of the stores, the brick-and-mortar versions of which were located in close proximity, for interviews. The quotas were established for the interviews and eventually had to be used for the first part of the survey.

Admittedly, convenience sampling has its limitations; specifically, it is a nonprobability approach, which makes the sample less likely to be representative (Benzo, Mohsen & Fourali 2017; Creswell & Creswell 2017). However, the use of this method is explained by the study’s time constraints, and this limitation will be taken into account when interpreting the results of the research.

Eventually, three different samples were recruited for the different parts of the study. The first survey (or the first part of the survey) needed the people who used only online applications or only brick-and-mortar stores for their purchases. As it was anticipated, it was not very easy to find the people who would only employ one of the two approaches. Eventually, 37 exclusively online shoppers filled out the surveys, and this number was used to determine the quota for the offline ones; only the first 37 offline buyers were included in the investigation.

For the second survey, only the time constraints determined the sample. At the end of the investigation (that is, by the time the data were extracted and analysed), 1030 people had completed the survey. Therefore, no specific quota was proposed for this part of the study. However, the interviews had a quota that was introduced to fit the time constraints of the research and ensure that enough time was available for completing data analysis. Specifically, 10 experts who were the first to respond to the researcher were recruited for the study as it was initially planned.

In addition, it was initially planned to recruit five online and five offline buyers for interviews, but only two offline and one online buyer agreed to participate. As a result, seven additional buyers were recruited who made their purchases both online and offline. To summarise, the present dissertation reports the results of a mixed-methods study that surveyed a total of 1104 participants and interviewed 20 more people.

First Part of the Survey: Quantitative Methods and Gathering the Data

The quantitative methods of research have multiple applications, but a very common one is the testing of the presence or absence of any relationships between variables (Creswell & Creswell 2017). Given the fact that the first question of this study consists of testing a relationship, this dissertation needs to use quantitative methods. Specifically, surveys were employed to this end. With the help of surveys, the study gathered quantitative data that could be used to answer the first research questions.

A survey is a self-report tool that offers respondents to consider a set of questions with responses (Eriksson & Kovalainen 2016; Hair et al. 2015). Surveys are a commonly used quantitative method of data collection (Creswell & Creswell 2017), which is typically employed to draw inferences from a population. Web-surveys are also becoming increasingly popular; they are more convenient than paper surveys from multiple perspectives, including relative accessibility and simplicity in conducting and data extracting (Bryman & Bell 2015). Thus, the use of this method in this dissertation is justified.

The independent variable consisted of using or not using online shopping applications. The dependent variable (impulse buying) was measured with the help of frequency (from “never” to “always” using a 5-point Likert scale), which means that the tool employed an ordinal scale for it. Thus, this part of the research was based on the idea that objective reality can be measured (Eriksson & Kovalainen 2016). This way, the use of online applications and impulse buying was prepared for checking if a relationship between them could be found.

The primary limitation of this part of the research is its sample. The study found that it was difficult to recruit the people who were exclusive in their use of online shops. Apparently, this approach to shopping has not become sufficiently common to completely substitute brick-and-mortar stores for the population that the researcher could contact. As a result, the total sample of the survey amounts to 74 people.

Given that the data were tested for statistical differences in the means of the responses using a test that could be applied to small samples, the results should still be relevant. However, the sample is very small, which means that additional research with other samples that can be gathered from particular populations would be required for conclusive statements on the topic.

Second Part of the Survey: Additional Data

In addition to the data that were meant to test the relationship between the two variables, the survey sought to investigate this relationship and attempt to explain it. As a result, additional questions were included in the data collection tool. Since the research involved both online and offline stores and since the latter was used as a counterpoint to the former, the survey tool included questions about both. The data from this part of the survey are of interest on their own, but it was also explored in the interviews with store managers who provided further commentary on the topic.

Regarding the limitations of this part of the research, the most important ones are connected to the sample. The participants remained completely anonymous, and they were recruited using English-speaking social media. As a result, it is difficult to make assumptions about the populations that the recruited people represent. In addition, while the sample is not small (1030 people), it is also not very big and cannot be used to make assumptions about online and offline shoppers in general. Thus, this part of the survey has limited generalisability, which should be taken into account when considering its findings.

Qualitative Methods and Exploring Phenomena

Unlike quantitative methods, qualitative ones exist to explore phenomena that cannot be quantified (Creswell & Creswell 2017). It can be suggested that there are the means of quantifying impulse buying; for instance, this research quantifies the frequency of buying to this end. However, in order to describe the reasons or effects of impulse buying, it is necessary to employ qualitative methods, and in this study, interviews are proposed to this end.

Interviews are very common qualitative data collection method. It can be argued that they are the most common approach used in qualitative research (Bryman & Bell, 2015). In this study, its choice is explained by the aim of the dissertation: it intends to gather the viewpoints of the people who have experience with impulse buying, especially specialists in the field, which is one of the methods of investigating phenomena (Creswell & Creswell 2017; Creswell & Poth 2016; Hair et al. 2015).

Further, this element of the study appreciates and employs the idea of the social construction of knowledge that is acknowledged by the critical realism paradigm (Eriksson & Kovalainen 2016). Thus, the use of interviews to respond to the research questions of this study is justified.

The specific type of interviews that were used can be described as semi-structured. In other words, the interviews used a protocol to ensure that they provide the questions for the participants to answer, but they also allowed the interviewees to add their own comments that are connected to the topic, offering a certain degree of freedom in their responses (Bryman & Bell 2015; Hair et al. 2015).

This approach was chosen because it has the benefits of both structured and unstructured interviews: on the one hand, the participants are guaranteed to provide relevant information, and on the other hand, they can also offer the data that is not directly covered by the interview questions but may still be relevant (Bryman & Bell 2015). The interview protocols were developed specifically for the research, which is a common approach to creating protocols (Bryman & Bell 2015; Hair et al. 2015). Customisation ensures that they cover the topics of interest for the dissertation.

The interviews took place in the settings chosen by the interviewees. The researcher transcribed the interviews during the procedure, and the resulting documents were shown to the interviewees. They checked the transcriptions for any mistakes and misrepresentation of their words, after which the interviews were approved by them. On average, the interviews took less than one hour, including the process of checking the transcription.

There are certain limitations to the method of interviewing. It is important to remember that interviews produce subjective data that is not generalisable (Bryman & Bell, 2015). In other words, interviews are not typically used to make conclusions about large populations. However, since their aim consists of exploring a phenomenon, this issue is not very problematic: generalisation is not one of the goals of interviews (Eriksson & Kovalainen 2016; Hair et al. 2015). The lack of generalisation is simply one of the features of interviews that should be taken into account when reviewing their findings.

Statistical Methods of Data Analysis

In this section, the statistical methods of analysis that were used by this dissertation will be investigated and explained. First, it should be mentioned that statistical analysis is commonly used to process quantitative data, which explains its application to the present study. In particular, survey data is commonly analysed with the help of descriptive statistics (Heeringa, West & Berglund 2017; Holcomb 2016).

In addition, inferential statistics can be employed to test hypotheses, including those that allow determining relationships between variables (Creswell & Creswell 2017). As a result, the present research employed both types of statistics for their respective purposes.

Thus, the data from the first part of the survey used a statistical test termed the Mann-Whitney U test. Certain considerations allowed choosing the test, and the process was guided by the modern literature on statistical analysis (Momeni, Pincus & Libien 2017; Weaver et al. 2017). First of all, the task of the study was to establish if a relationship between two variables (shopping in online or offline stores and making impulse purchases) could be found. Second, in order to achieve that, the study involved gathering two sets of data: one for online purchasers and one for offline purchasers. The data were ordinal, and the sample was rather small. Based on this information, it was determined that the Mann-Whitney U test could be used for testing the hypothesis.

Indeed, the Mann-Whitney U test can be used with ordinal scales and small samples to compare two sets of data. To be more specific, it allows checking if their distributions, as well as medians, are similar (Momeni, Pincus & Libien 2017). If they are not, it can be suggested that a relationship between the two variables is present; if they are, the test does not allow suggesting a relationship between them. As for the second part of the survey, descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data and represent it using graphs (Heeringa, West & Berglund 2017; Holcomb 2016). The results will be presented below.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis was chosen because it is a very common and well-established approach to working with qualitative data (Braun & Clarke 2016). In addition, it can be used when working with interviews (Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2016).

The method can be defined as the development of the so-called “themes” which can be used to represent the gathered data (Vaismoradi et al. 2016). While there is no established definition of the term, themes can generally be described as certain patterns that emerge from the studied information (Braun & Clarke 2016; Eriksson & Kovalainen 2016). They are also comprised of individual “codes,” which are the labels that are used to distinguish particular ideas within the data (Vaismoradi et al. 2016). Thus, thematic analysis usually involves studying the gathered data, labelling its key ideas with codes, and using the codes to establish relevant themes.

For this research, the following structure was applied to its thematic analysis. First, the researcher got acquainted with the data by repeatedly reading the transcripts of the interviews. Second, the important codes within the interviews were distinguished. Third, the codes were used to determine themes. Fourth, the themes were checked and refined to establish their ability to represent the data. Finally, the themes were transformed into a narrative that was presented and included in this dissertation. The results of the analysis can be found in the following chapter.

Ethical Considerations

The primary ethical considerations that are important for this study are connected to the rights of research subjects or participants. The present research did not involve significant risks, but still, several topics had to be reviewed. They included voluntary participation and confidentiality (Bryman & Bell, 2015; Roberts & Allen 2015). Depending on the method, the approaches to resolving these issues were different.

With surveys, confidentiality was simple to achieve. In fact, unless a survey includes identity-exposing questions, Survey Monkey does not produce any kind of identifying information. As a result, the complete anonymity of the survey participants was ensured by leaving the survey tool without identifying questions.

The topic of voluntary participation was more complicated since the anonymity feature also made it rather difficult to ensure the informed consent of the participants. However, all recruitment materials included the information about the study and the explanation of the fact that the participation was supposed to be voluntary. As a result, it was assumed that if a person decided to respond to a survey, they consented to participating. Also, it should be noted that even though the Survey Monkey offers the option of skipping questions, none of the 1030 participants skipped any of the questions of this study. It can be assumed that the participation did not cause them any significant distress, which was anticipated since the questionnaire did not include problematic questions.

Unlike the survey, the interviews could not offer the participants anonymity, which is why confidentiality precautions were required. The interviews involved some questions about the participants’ workplace, but they never required naming them, and the identifying information was not collected. Further, all the potentially identifying information was edited out of the transcripts, and no personal information was included in this report. It is also not planned to disclose any identifying or personal information in any future papers that might employ the results of this study. The transcripts and the informed consent documents provided by the participants will be preserved in a secure location and eventually destroyed.

To ensure voluntary participation, the interviewees were provided with informed consent documents. The documents included all the information about the study and its procedures, as well as the confidentiality precautions and potential risks of the participation. The informed consent was provided to the participants before the arrangements for the interviews were made, and they were signed before the interviews. In summary, despite the minimal risks of participating in this study, the ethical considerations of the participants’ rights were taken into account and appropriately addressed.

Findings

Survey: The Comparison of Online and Offline Buyers

During the implementation of the study, it proved to be difficult to find the people who buy things only offline or only online. First, the survey was used to gather a sample of online-only buyers, and it managed to collect 37 responses of the respondents who claimed to only buy things online through online shopping applications. Then, a survey for offline only buyers was launched, and the first 37 people to respond to it formed the second part of the sample for this part of the research. Thus 74 people were involved in the survey that gathered the information about the buying behaviours of exclusively online or offline buyers.

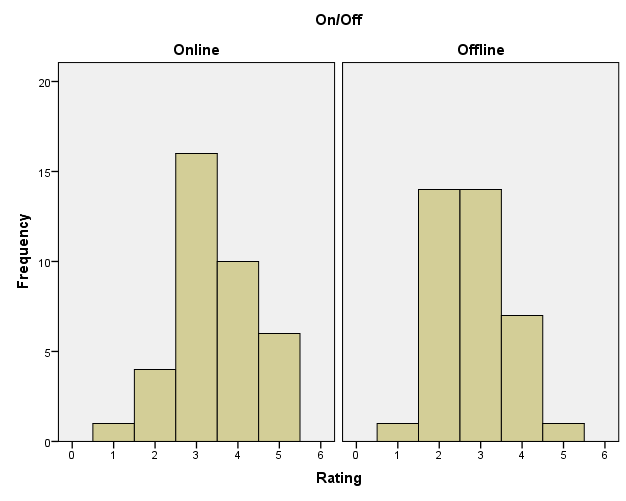

The question that both groups were asked to consider was the same: how often do you buy things spontaneously? The questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale. The results are presented in the following figures. Figure 1 shows the different distribution of answers; in it, number 1 stands for “never,” and number 5 stands for “always.”

Figure 2 shows a category-by-category comparison of the responses. From it, it is visible that offline buyers were more likely to choose the responses “rarely,” “sometimes,” or “often,” and those buying online tended to choose “sometimes” and “often.” Also, both groups were unlikely to choose the response “never,” but more online buyers chose the option “always.”

Figure 3 shows that overall, the response “sometimes” was the most frequently used one. In general, it appeared that the respondents were not very likely to choose the options “never” or “always.”

Figure 4 shows the results of grouping the options “never” with “rarely” and “often” with “always.” Figures 1, 2 and 4 indicate that online buyers from the sample reported buying things spontaneously more often than offline ones. However, a statistical analysis is required to determine if this tendency has a statistical significance.

From Figure 1, it is apparent that the distribution of responses is not normal, which was one of the factors that allowed determining the appropriate statistical test to be used for the study. In particular, the fact that the distribution is not normal implies that the criteria for t-test were not met by the data. Given the fact that the survey produced ordinal data with two independent samples, it became apparent that Mann-Whitney U test was supposed to be employed to determine the presence or absence of a statistically significant difference between the two samples (Momeni, Pincus & Libien 2017; Weaver et al. 2017). The data were entered into an SPSS worksheet, and the results of the analysis can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1: Mean Ranks for Online and Offline Buyers.

Table 1 demonstrates the differences between the mean ranks of the two samples. As can be seen from it, the mean rank of online buyers is higher than that of offline buyers, which makes sense since it is clear that the former group reported greater frequencies of impulse buying more often (see Figure 4). However, this information is not enough to make conclusions about the statistical significance of the difference, for which Table 2 should be considered.

Table 2: Statistical Significance of the Difference between Online and Offline Buyers.

Table 2 includes the p-value, and as can be seen from it, when corrected for ties, p=0.005. Typically, in order to state that the difference in the responses between the two groups is statistically significant, the p-value needs to be below 0.005 (Momeni, Pincus & Libien 2017). In this case, p=0.005, which is why it can be inferred that the difference is not actually statistically significant, even though it is very noticeable.

Other Survey Data

Only a small sample of respondents was found for the first part of the survey. However, the rest of the survey could be applied to the people who used both online and offline means of shopping, which allowed gathering a bigger sample. In total, 1030 people responded to the rest of the survey. This section will present the results of this part of the research.

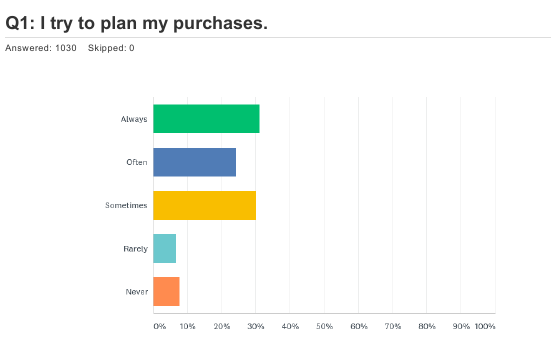

Several major topics were covered by the survey. First, it allowed characterising the sample. Basically, the absolute majority of the respondents reported trying to plan their purchases with only 7.77% never doing so. Over 30% of the respondents always plan their purchases, another 30% do so sometimes, and almost 25% do so often (see Figure 5).

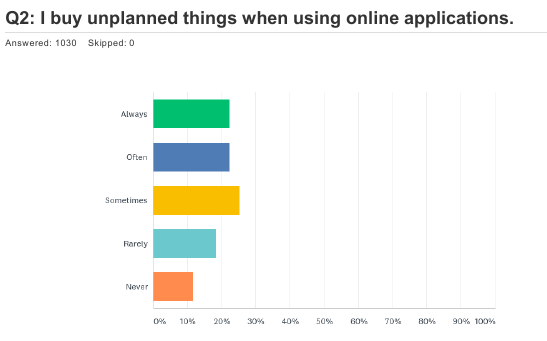

However, Figure 6 shows that only 11.65% of the respondents never buy unplanned things using online applications. 22.33% report that they always buy something unplanned online, and the same number of people do so often. More than 25% of the sample buy unplanned things online sometimes, and 18% do so rarely.

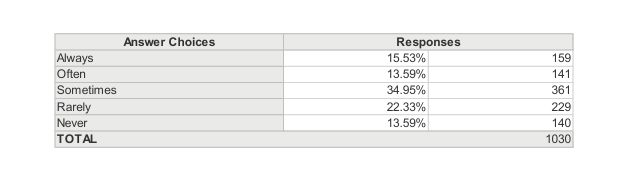

When responding to the third question (see Table 3), the participants were meant to consider the cases when they buy unplanned things in brick-and-mortar stores. Here, almost 14% of the sample believe that they never buy unplanned things in offline stores, and only about 15% of them do so always. The majority of the sample do so sometimes (almost 35%) or rarely (22.33%). A few people do so often (almost 14%).

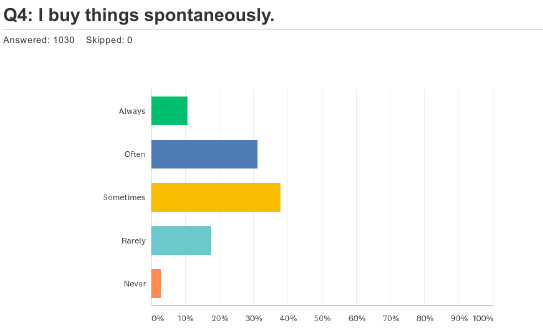

Finally (see Figure 7), only 3% of the respondents claim that they never buy things spontaneously. Most of them (37.86%) engage in impulse buying sometimes, many do so often (31.07%), a few do so rarely (17.48%), and some do so always (10.68%).

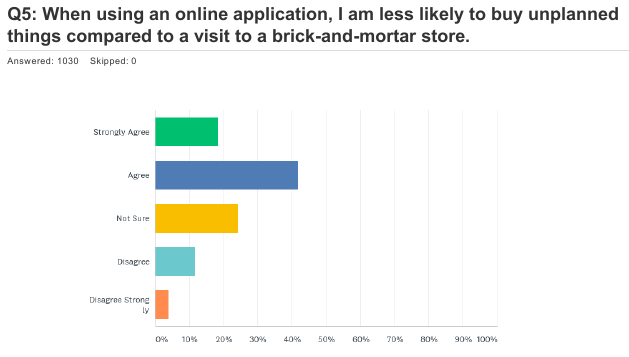

Further, the respondents were invited to compare their buying behaviours in online and offline stores. When asked if they were less likely to buy unplanned things in online applications, the majority (41.75%) of them agreed with the idea, and 18.45% strongly agreed with it. However, a little over 15% disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 24% were not sure about their perspective (see Figure 8).

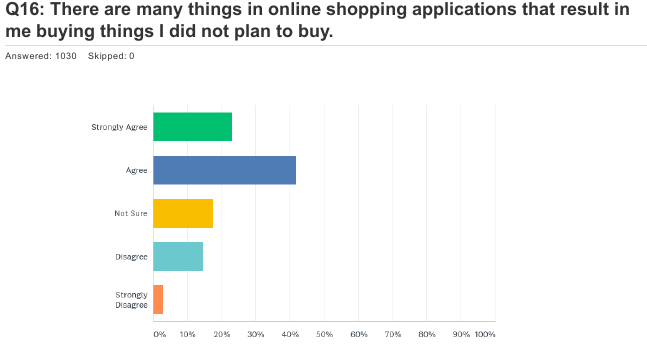

On the other hand, most respondents agree (41.75%) or strongly agree (23.30%) with the idea that online applications have the means of inducing impulse buying. Basically, only 17.47% of them disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement (see Figure 9).

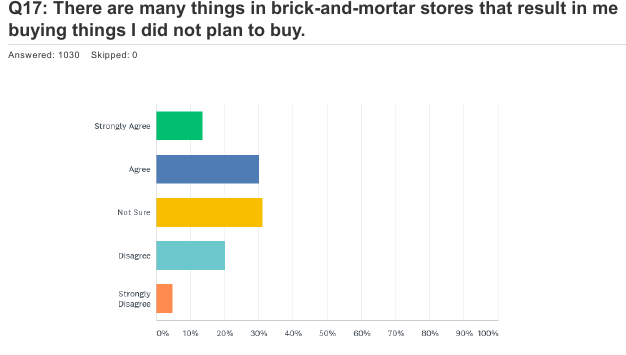

Similarly, many people believe that offline stores have the means of promoting impulse buying; a total of 43% agree or strongly agree with the idea (see Figure 10). However, 31% were not sure with their response, and more than 25% disagree or strongly disagree with the statement. Thus, even though the majority of the respondents report being more likely to buy impulsively from a brick-and-mortar store, fewer of them believe that offline stores can promote impulse buying when compared to the number of them certain that online applications can achieve the outcome.

In addition, the survey provided the research with the opportunity of investigating the efficacy of the different approaches to promoting impulse buying that can be employed in online or offline stores. The information about the methods was taken from the literature review, but the respondents were invited to provide their personal opinion about their effectiveness by measuring their ability to influence the personal impulse buying behaviour of the participants.

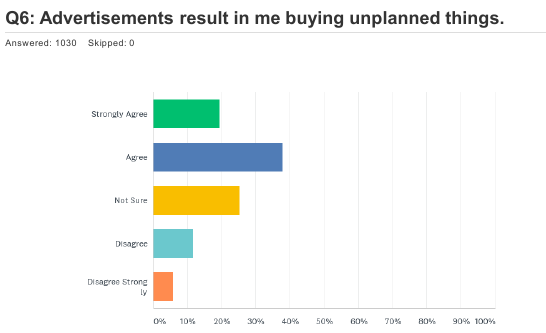

Figure 11, for example, demonstrates that a vast majority of the respondents consider advertising to be a factor that can influence their impulse buying: 19.42% strongly agree with the idea, and 37.86% agree with it. Still, 11% disagree, almost 6% strongly disagree that advertising can make them buy something unplanned, and 25% remain unsure about their perspective on the topic.

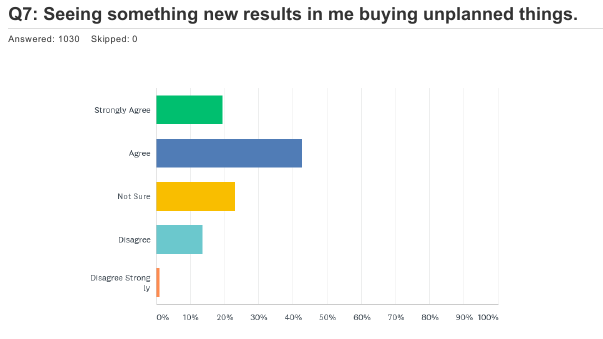

Figure 12 shows that even more people believe that seeing new things can result in impulse buying. Specifically, 19.42%stongly agree with this statement, and 42.72% agree with it. 23% of the respondents could not decide what to respond, and only less1% strongly disagreed with the idea; almost 14% disagreed with it.

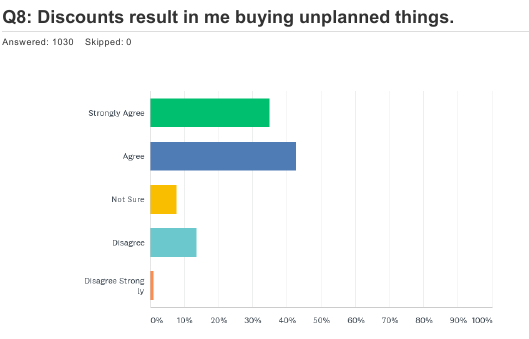

Figure 13 represents the respondents’ attitude towards discounts. More than 34% strongly believe that discounts improve impulse buying, and 42.72% agree with the idea. Only less than 8% are unsure, and less than 1% strongly disagree, although almost 14% do disagree with the notion (see Figure 13).

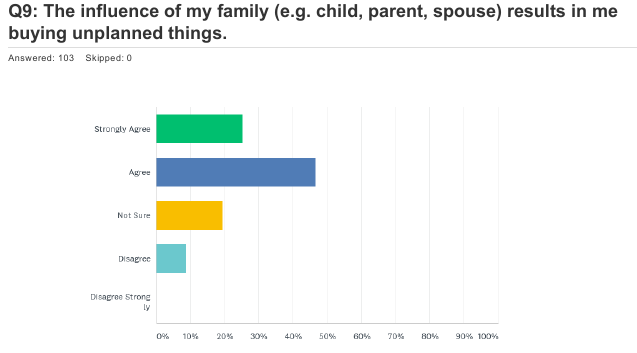

The impact of the family is also very significant; only 8.74% of the respondents believe that the family cannot make them buy unplanned things, and almost 20% are not sure. However, 25% and 46% strongly agree or just agree with the idea that the influence of one’s family can promote impulse buying (see Figure 14).

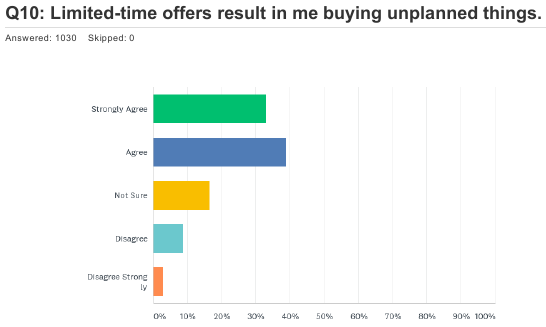

Limited-time offers are also an important factor for at least 71% of the respondents who agree (38%) or strongly agree (33%) with the idea that they promote impulse buying. More than 11% disagree, however, and 16% remain unsure (see Figure 15).

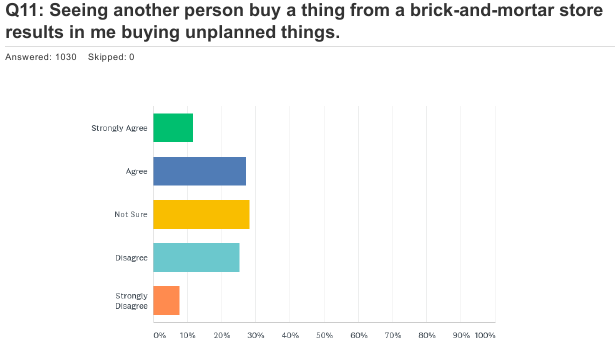

The next few questions considered the methods that could be employed either in a brick-and-mortar store or an online one. For example, Figure 16 demonstrates that 28% of the respondents are not sure if seeing another person buy something in an offline store would make them buy something unplanned. However, 11% of the respondents strongly believe that this factor would increase impulse buying, and 27% simply agree with the idea.

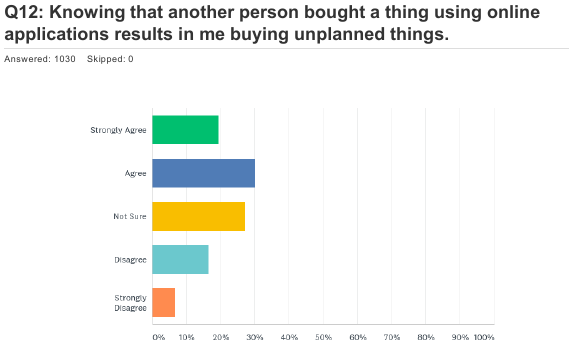

Still, 25% disagree, and 7.77% strongly disagree with the notion. The results for knowing about another’s purchase in an online store is only slightly different (see Figure 17). 19.42% strongly agree with the idea that this factor would promote impulse buying, and 30.1% agree with it, but 6.8% strongly disagree, and 16.5% simply disagree with it. The rest remained unsure of their response.

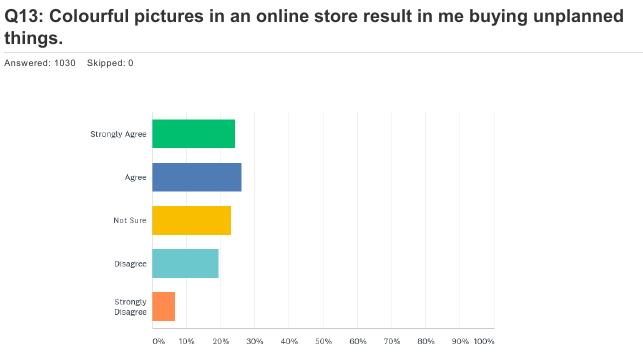

As shown by the literature review, online stores can employ pictures to stimulate impulse buying. 24.27% of the respondents strongly believe that this approach would yield results, and 26.21% also agree with the idea, but 19.42% disagree and 6.8% strongly disagree with it (see Figure 18).

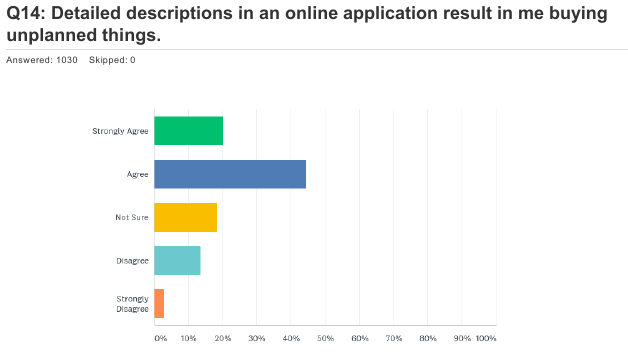

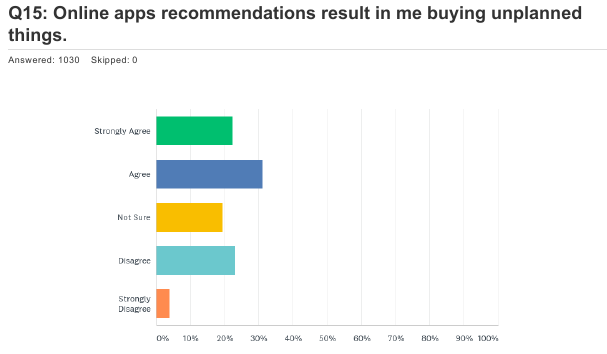

Figure 19 shows that many of the respondents agree (44.66%) or strongly agree (20.39%) that detailed descriptions in online applications improve impulse buying. 13.59% disagree, and 2.91% strongly disagree with the idea. The recommendations in online apps can also improve impulse buying according to 53% of the respondents (22% strongly agree, and 31% agree). However, 23.3% disagree with the idea, and 3.88% strongly disagree with it.

Interview Results: Managers

The analysis of the interviews allowed establishing the following key themes within the data. First, the majority of the interviewees commented on the importance of impulse buying for their businesses. Based on their reports, it can be concluded that managers generally understand the significance of impulse buying, but they do not always employ this term. Many of them also note that their businesses do not directly include the term or the strategies for promoting impulse buying in their business plans. One manager suggests that most people buy things spontaneously at least sometimes, and a few noted that they became used to buying things impulsively.

Two managers noted that impulse buyers are “unexpected” or “unscheduled,” which could make them difficult to handle, but they also reported that their shops employed different techniques which could improve impulse buying. In other words, even if they are not sure that impulse buying is always convenient, they still appear to support the notion of promoting it. For example, a clothes shop manager commented on the display of various accessories (shoes, necklaces, and so on) in brick-and-mortar stores as a method of prompting unplanned buying.

Similarly, another manager noted the creation of sets of clothes both in online and offline stores, in which individual pieces of clothing were matched together to create a “stylish ensemble.” Other methods that could be used by both online and offline stores and that were mentioned by at least two managers included discounts, advertising, and limited-time offers. ‘

Regarding the methods of improving impulse buying in online applications, many participants commented on pictures and descriptions; also, several participants pointed out the possibility of including recommendations and rating systems. In this context, recommendations included offering a user similar products or ones that could be bought together with the one they appeared to be interested in; for instance, if a buyer is considering buying a shirt, they could be recommended pants or jeans.

One of the managers noted that online assistants could also promote impulse buying, and two commented on the importance of a convenient and appealing application design. When discussing the possibility of promoting offline impulse buying, most participants considered displays and attendants.

When considering whether online or offline stores could have more options for promoting impulse buying, the majority of the respondents suggested that online stores are in a more advantageous position. Their arguments included the convenience of online stores (that is, the fact that a person does not need to spend much time travelling to them) and the possibility of employing all the above-described methods of promoting impulse buying.

However, several interviewees disagreed and pointed out that the possibility of seeing a product and touching it, as well as checking its quality and state, increased the possibility of impulse buying in brick-and-mortar stores. From their perspective, this advantage was greater than that of descriptions and pictures. Similarly, one manager suggested that the interaction with a shop attendant was more likely to result in impulse buying than various recommendation features in an online shop.

In addition, an important theme to consider was the tendency of the interviewees to describe their plans for future investment in online shopping, including the development of the features that would promote impulse buying online. One manager stated that “online stores are easier (to use)” and “cheaper to maintain.” According to him, cheaper maintenance of online stores also implies the possibility of making the goods cheaper, as well as introducing more discounts and other special offers.

Further, another manager commented that “more people use online stores nowadays,” which implies that the brick-and-mortar stores should establish an online presence. The majority of the interviewees reported that nowadays, brick-and-mortar stores benefit from having an online presence, and one manager expressed the idea that “online stores are the future.”

Interview Results: Buyers

The analysis of the buyers’ interviews resulted in the development of themes similar to the ones present in the responses of the managers. First, the interviews were carried out only with the participants who experienced impulse buying, and their accounts of the events mostly supported the above-presented examples of the techniques that can promote impulse buying.

Specifically, the following factors were reported as significant: discounts and limited-time offers, which were mentioned by all respondents, advertisement, which was mentioned by 7 respondents, the impact of other people (including watching another person buying a thing or knowing that another person bought a thing), which was mentioned by four respondents. In addition, three respondents noted that visiting brick-and-mortar shops with their children almost always resulted in buying unplanned sweets or toys for them.

When discussing the influence of sales assistants, the majority of the participants agreed that they could potentially result in impulse buying. However, two participants noted that they disagree with the idea. One of them finds sales assistants “annoying,” which makes him less likely to buy a thing if he is approached by them, and the other one does not consider them to be an important factor.

When reviewing the methods that can only be used online, all participants mentioned pictures and recommendations, and six of them mentioned descriptions. It is noteworthy that five of the participants pointed out that the quality of pictures and descriptions are very important: according to their accounts, if the pictures are good, they can promote buying, but if they are not sufficiently well-made, they discourage buying.

Another noteworthy finding is that the majority of the respondents did not find impulse buying to be problematic. Only one of them commented on it being a concern from the financial point of view, and most also noted that it could become problematic for some people but not for them. Regarding the comparison of online and offline shops, most people found it difficult to compare their experiences.

All of them noted that they bought impulsively in online and offline shops, but three of them suggested that they would be more likely to purchase a thing spontaneously offline because “it is right there in front of me,” “I can touch it,” and “I can take it without even thinking.” In other words, some of the participants believe that offline stores have the advantage of the physical presence of the product. The convenience of online applications was also noted by the majority of the participants, but they did not connect it to impulse buying.

The participants were also asked to consider the results of the surveys. They commented that impulse buying was indeed a common thing for both online and offline shops, and they generally agreed that both online and offline stores have a lot of features that promote impulse buying. However, most of the respondents suggested that the differences between the results for the online and offline impulse buying were not very significant.

Analysis and Discussion

Based on the results of the two surveys and two types of interviews, as well as the literature review, the following conclusions can be made. Firstly, all the findings indicate that impulse buying is a significant notion to consider. Indeed, aside from the literature review (Lai 2017; Lin & Lo 2015; Thompson & Prendergast 2015), both groups of interviewees agree that it is important for modern businesses.

Further, the surveys demonstrate that, on average, few people report never experiencing impulse buying, and quite a number of people note that they buy spontaneously very often, which is also similar to the findings of the literature review (Lin & Lo 2015; Thompson & Prendergast 2015). In general, most people appear to have impulse purchases “sometimes,” which indicates that the phenomenon is relatively (or subjectively) common. The managers directly indicate that investing in impulse buying promotion is a good idea. Thus, the findings support the assumption that impulse buying is a significant topic for modern businesses.

Secondly, this research cannot indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between the impulse buying behaviour in online and offline buyers. Just like the reviewed research (Lee, Park & Jun 2014; Park, Jun & Lee 2015), the present one is not sufficient for making such statements, especially since it is the first study to focus on the impact of online shopping applications on impulse buying.

The first part of the survey does show that there are some differences between the two groups, which is especially visible in the distribution of the responses (see Figure 1). However, the statistical analysis does not indicate that the discrepancy is statistically significant. It should be pointed out that the limitations of the Mann-Whitney U test, as well as the sample, may have affected the results (Momeni, Pincus & Libien 2017). Also, the sample does indicate a notable tendency for online shoppers to buy impulsively more often; the difference between the two groups is noticeable, even if it is not statistically significant. Still, for the time being, it is impossible to state that a relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying exists.

It should be pointed out that a similar discrepancy is present in the second part of the survey. For example, more people reported buying unplanned things with online applications more frequently when compared to buying things offline (see Figure 6). However, quite a number of people also noted that they were less likely to buy unplanned things in an online application when compared to offline stores (see Figure 8).

The questions do not directly contradict each other, but still, a certain discrepancy can be found in these figures. The reason for such contradiction could consist of the self-reported nature of the data: after all, people might believe that they are more likely to buy unplanned things offline but still evaluate their unplanned purchases as more frequent when done online. Similarly, while the majority of the interviewed managers suggested that online shopping applications should be better for impulse buying, the few buyers who commented on the topic disagreed. This discrepancy can be explained by different perspectives and experiences of the interviewed people; after all, interviews cannot be used to make generalised assumptions about particular populations.

The surveys and interviews demonstrated that the literature on the topic is correct in assuming that impulse buying can be promoted (Amos, Holmes & Keneson 2014; Badgaiyan & Verma 2015; Lai 2017). Some of the methods that were found effective by at least some of the respondents include advertising, discounts, limited-time offers, and the influence of other people (family, celebrities, just other people purchasing a thing).

Regarding the methods that are exclusive to offline stores, the participants commented on sales assistants; also, some of the respondents highlighted the benefits of being able to see and touch a product. Regarding the things that an online store can do, the participants highlighted the importance of design, pictures, and descriptions, as well as recommendations sections, which is also in line with the reviewed research (Rezaei et al. 2016; Vonkeman, Verhagen & Dolen 2017). It is noteworthy that the quality of these features appears to be important; low-quality pictures and descriptions at least were described as a deterrent.

It should be mentioned that while the majority of the respondents of the second part of the survey believe that they are more likely to buy impulsively offline, the idea that online stores have many methods of promoting impulse buying was supported by very many people. This finding might indicate that online stores do not manage to use impulse buying promotion strategies to their fullest extent. It can also be connected to the fact that many managers reported not using the term and not including it in their business strategy. However, this conclusion is rather speculative; the data cannot be used to prove that online stores do not use impulse buying promotion strategies very extensively.

Most importantly, however, as shown by the research, people have rather different attitudes towards different methods of shopping and strategies of impulse buying promotion. This finding is also in line with the literature review: as it was mentioned, impulse buying is affected by numerous factors, which makes this type of behaviour very variable (Amos, Holmes & Keneson 2014; Lai 2017). While there are certain tendencies towards favouring one strategy of enhancing impulse buying over another, all of them have some supporters. Similarly, while some people are more likely to buy impulsively online, others are more likely to buy impulsively offline.

Based on these findings, the following recommendations can be made. The interviews with the participants, while not very representative, still demonstrate that some businesses do not explicitly consider impulse buying and do not work towards promoting it. However, given the significance of impulse buying for both online and offline stores, it may be logical to introduce impulse buying considerations into one’s business strategy. Since impulse buying is a common phenomenon, it makes sense to invest in it. The different approaches to impulse buying that were found in the literature on the topic and tested in the present study seem to be effective in promoting impulse buying in at least some of the buyers.

Given the varied attitudes towards those approaches, it would make sense to diversify one’s strategy for promoting impulse buying by employing several of them. It is noteworthy that the majority of the methods are commonly employed to attract buyers and improve their shopping experience, which makes them even more valuable for businesses. Finally, since the present research is not representative of any particular population, it may make sense to conduct surveys for one’s target market. With online stores, this strategy would be particularly simple to implement.

Limitations

It is very important to remember the limitations of this study, which are determined by the limitations of its research methods. First of all, all the data is self-reported, which is why it is necessary to make an assumption that the respondents offered truthful answers. Secondly, the participants do not have to be untruthful (that is, consciously lie) to provide inaccurate answers; they might misreport data unconsciously. For instance, a person might not register or remember the instances when they bought impulsively and report that they have never done so. Thirdly, while the Likert scale is a very commonly-used method, it is not very precise.

For one respondent, “often” may mean once a week, and for another, it could be twice a month. In other words, the responses of the survey are subjective, which limits the researcher’s ability to make conclusive statements about the frequency of impulse buying in the sample. The same can be said about the interviews, but for them, subjectivity is a feature, which is why it is unavoidable. From the perspective of critical realism, the impact of subjectivity can be explained by the fact that knowledge is socially constructed; it is to be expected and needs to be taken into account when interpreting the findings.

Further, the sample is unlikely to be representative, which is especially true for the first part of the survey and the interviews. Indeed, these two parts of the research have small samples, and while this factor is explained by the specifics and constraints of the research, it still should be taken into account when considering the findings. The first survey and interviews should not be used to make significant conclusions about large populations. The sample of the second part of the survey is noticeably bigger, but since the participants are completely anonymous, it is difficult to associate it with a particular population.

Thus, it is apparent that the methods of the study have some inherent flaws. However, it should be pointed out that the employment of different methods counters their effects. Indeed, the results of the surveys and interviews present responses to similar questions, which allows comparing them and making conclusions about the presence or absence of tendencies in them. For instance, the first part of the survey may be used to imply that online buying could be more associated with impulse purchasing, but the survey yielded different results. Thus, the triangulation of the methods prevents this dissertation from making inaccurate conclusions. As a result, the study contributes some data to the research on the topic, but the sources and specifics of these data must be taken into account while interpreting them.

Recommendations for Future Research

The present research can contribute some information about the way future studies can investigate the same topic. There is little research on the impact of online buying on impulse buying, and very few studies even mention online shopping applications (Park, Jun & Lee 2015), which is why the following recommendations can be made. First, the methods employed by the study have their significant limitations, which can be rectified in future research.

It may be reasonable to employ more objective methods of measuring impulse buying (for instance, “once a week” instead of “often”) in future investigations. Further, it could help to establish a population of interest to be able to recruit a representative sample. For instance, a more practically-applicable study could investigate the preferences of a particular city for a local business or the users of an online store. Also, the fact that the study did not focus on specific types of stores is noteworthy. It may be helpful to choose a particular industry to consider (for instance, clothing or food).

Regarding the impact of online shopping applications on impulse buying, the present dissertation was met with the problem of finding the people who visit only online stores. Possibly, a future study that has an opportunity to spend more time on recruiting will be able to find a larger sample. Alternatively, it is possible to study the populations’ accounts of their experiences in both online and offline shops and compare them for any meaningful tendencies. Thus, the future research on the topic can eliminate some of the limitations of the present one and provide solutions for the problems that it encountered.

Conclusion

This dissertation sought to find out if there is a relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying behaviour with the help of a mixed-methods research. Having reviewed the literature on the topic and conducted two surveys and two sets of interviews, this paper can offer the following conclusions. According to the present research, as well as the findings of this study, it is impossible to claim that there is a relationship between online shopping applications and impulse buying.

A number of the respondents report experiencing impulse buying in online applications, and the first survey does show a tendency for more frequent impulse buying among online-only buyers. However, many participants also believe that they are more likely to buy impulsively offline, and the difference between the online-only and offline-only buyers is not statistically significant.

It should be pointed out that the present study has a number of limitations, which have affected its outcomes. The sample for the first part of the survey was small, which is why it cannot be very representative. Future research may be able to avoid such limitations and provide more specific results. Thus, this study cannot be used to claim that shopping applications promote impulse buying, but it also cannot be used to claim that there is no relationship between the two variables.

The rest of the findings suggest that shopping applications, as well as offline stores, might promote impulse buying with the help of a number of strategies, which are also present in the literature on the topic (Amos, Holmes & Keneson 2014; Badgaiyan & Verma 2015; Lai 2017). These strategies might be considered the reasons for impulse buying in shopping applications, and they include multiple promotional activities like advertising, recommendations, and so on. As for the impact that online shopping and impulse buying can have, this study supports the idea that impulse buying is a common phenomenon that businesses can use to their benefit.

Thus, the present research has responded to its questions despite not finding a direct relationship between its two key variables. The dissertation contributes some data to a topic that remains understudied (Badgaiyan & Verma 2014; Rezaei et al. 2016). Further, it offers some practically applicable findings for modern businesses. Future investigations on the topic may target specific populations or industries and employ bigger samples.

Recommendations

The findings have some implications for modern businesses. Based on the reports of the managers, some stores do not directly consider impulse buying when developing their strategies and business plans. However, given the importance of the phenomenon, it may be a logical course of action to change that. The gathered data, as well as other literature on the topic, quite reliably suggest that it is possible to promote impulse buying. Given the benefits of this behaviour, as well as the fact that it has been reported to be the cause of a large percentage of purchases both online and offline, the stimulation of impulse buying should be of interest to businesses, including those that use online applications.

The present study also demonstrates that diverse impulse buying promotion techniques can assist businesses. The collected information indicates that online shopping applications may be at a disadvantage when compared to brick-and-mortar stores since the latter have greater interactivity and can employ the environment to boost customer experience.

However, applications have the benefit of being more convenient and accessible, and they can mimic the interactivity of offline stores by using effective and engaging design, good-quality images of products, and various rating or feedback systems. In addition to that, any store or application benefits from many approaches to promoting products like discounts, limited-time offers, advertising, and so on; all these factors improve impulse buying. Thus, these strategies of promoting impulse buying in online applications can be suggested for use.

The final recommendation is informed by the fact that the responses to the survey were rather diverse. The respondents assessed the effectiveness of various methods of prompting impulse buying very differently. Similar patterns are also found in other literature and can be explained by the fact that personal factors can affect impulse buying. As a result, it may be helpful to employ diverse methods of promoting impulse buying to increase the chance of them having an impact on customers.

In addition, it should be mentioned that the attitudes of the respondents of this survey are not representative of a particular population, but a store might consider employing a similar survey to determine the methods preferred by its clients. In summary, the present research recommends paying attention to the notion of impulse buying, developing strategies aimed at its promotion, and, if possible, customising such strategies.

Reference List

- Akram, U, Hui, P, Kaleem Khan, M, Tanveer, Y, Mehmood, K & Ahmad, W 2018, ‘How website quality affects online impulse buying’, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 235-256.

- Amos, C, Holmes, G & Keneson, W 2014, ‘A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 86-97.

- Badgaiyan, A & Verma, A 2014, ‘Intrinsic factors affecting impulsive buying behavior – evidence from India’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 537-549.

- Badgaiyan, A & Verma, A 2015, ‘Does urge to buy impulsively differ from impulsive buying behaviour? Assessing the impact of situational factors’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 22, pp. 145-157.

- Badgaiyan, A, Verma, A & Dixit, S 2016, ‘Impulsive buying tendency: measuring important relationships with a new perspective and an indigenous scale’, IIMB Management Review, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 186-199.

- Bellini, S, Cardinali, M & Grandi, B 2017, ‘A structural equation model of impulse buying behaviour in grocery retailing’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 36, pp. 164-171.

- Benzo, R, Mohsen, M & Fourali, C 2017, Marketing research, SAGE, New York, NY.

- Bhuvaneswari, V & Krishnan, J 2015, ‘A review of literature on impulse buying behavior of consumer in brick to mortar and click only stores’, International Journal of Management Research and Social Science, vol. 2, no, 3, pp. 84-90.

- Braun, V & Clarke, V 2016, ‘(Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis,’ International Journal of Social Research Methodology, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 739-743.

- Bryman, A & Bell 2015, Business research methods, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Bues, M, Steiner, M, Stafflage, M & Krafft, M 2017, ‘How mobile in-store advertising influences purchase intention: value drivers and mediating effects from a consumer perspective’, Psychology & Marketing, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 157-174.

- Chan, T, Cheung, C & Lee, Z 2017, ‘The state of online impulse-buying research: A literature analysis’, Information & Management, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 204-217.

- Chen, C & Yao, J 2018, ‘What drives impulse buying behaviors in a mobile auction? The perspective of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model’, Telematics and Informatics, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1249-1262.

- Chen, J, Su, B & Widjaja, A 2016, ‘Facebook C2C social commerce: A study of online impulse buying’, Decision Support Systems, vol. 83, pp. 57-69.