Introduction

Life-Cycle Permanent Income Model, sometimes called Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH), is an economic theory that predicts human consumption and saving, considering future income possibilities. Milton Friedman framed LCH in the 1950s, and his idea that he wanted to prove is that humans plan their spending throughout their lives, considering future earnings (Kindermann & Krueger, 2022).

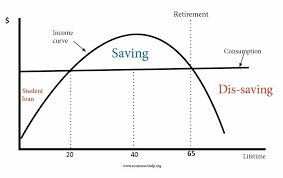

LCH theory implies that wealth accumulation from childhood to adulthood differs significantly. According to Kindermann and Krueger (2022), a graph of income consumption vs. age, as shown in Figure 1, indicates that children and the elderly spend less. On the contrary, middle-aged individuals and youths with secure jobs spend a lot since most have a permanent income source (Permanent income hypothesis, n.d.). Therefore, this paper illustrates why the Life-Cycle Permanent Income Model is a valuable theory for individuals to make wise decisions regarding consumption and saving, considering both current and future incomes and citing personal life experience.

Assumptions of Life-Cycle Hypothesis

LCH assumptions are the first step that one has to know to understand the concept held by Friedman. According to Gomes (2020), LCH has three significant assumptions that make the application of the theory accurate.

First, humans tend to smoothen their consumption regardless of their earnings (Gomes, 2020). This implies that people will live smoothly throughout the year even if their monthly income is erratic. Thus, it is expected that people will tend to save as much as they can when they earn more to cover up for months when they expect low pay/income.

However, when one expects a pay rise or a more income shortly, consumption becomes higher at the expense of saving. This is obvious because with more income expected, the mind is relaxed and does not worry about the following income for survival.

The second assumption of the models is that people are impatient and tend to consume more when the interest rates are zero (Econ, 2014). However, if the interest rates are favorable, consumers tend to delay their consumption since they consider inpatient costly in the long run.

The last assumption of LCH theory holds that people are forward-looking when making current consumption and saving choices. According to Kindermann and Krueger (2022), it was found that it is expected to base decisions on future expectations. For instance, people often consider future earnings when deciding how much they should save or consume. As such, children or high school students tend to consume little income since most are unemployed and still depend on their families for assistance.

On the other hand, adults and youths who are employed or doing business tend to consume many incomes because they have a daily or monthly permanent source of income. In addition, income consumption at an older age also becomes relatively low. The essence is that most older people consider retiring, and with little they have, they tend to dip in savings since they have no future permanent income to sustain higher spending.

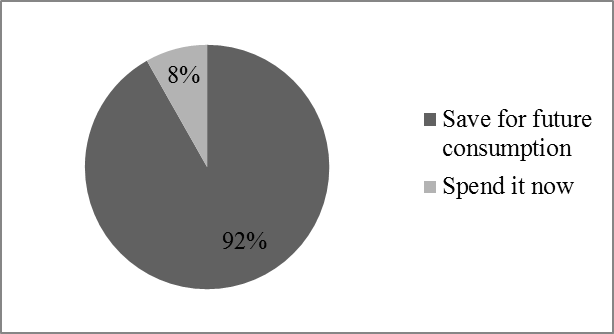

Sonderegger et al. (2020) researched and found that the elderly who are yet to retire consume little income while saving the most. Figure 2 below represents Sonderegger et al. (2020) findings regarding the elderly’s income consumption and saving. Therefore, the LCH theory holds that spending and saving depend greatly on future earnings/income.

Application of Life-Cycle Hypothesis to the Personal Life

Spending Money While in School

My family history of consumption, spending, and saving truly reflects LCH theory in practice. Starting with myself, the nature of how I have been spending money from my childhood up to now significantly relates to Friedman’s postulated theory. Being in elementary school and high school, I was given little money to spend for a whole semester. Considering I had no other income source, I would use the money meticulously and on necessary budgets only. This was so because I wanted to save as much as possible so that the money would be enough for the semester. Now that I am partly employed while doing my master’s, I have a permanent source of income, and my mind is relaxed. I now spend nearly ten times as I used to because I know my account is loaded with cash at the end of every month.

Spending Money in Retirement

On the other hand, my father is nearly retiring from his job, and I have noticed a change in his income spending/consumption. When he got a promotion in 2010 after serving for 20 years, my father bought a new Lexus car that consumes liters of gasoline, which he has listed for sale currently. I realized he was selling the car because he was retiring soon and did not want to spend his money on the car.

LCH theory comes into play because my father has no permanent income anymore. He is considering saving and only spending on necessary budgets for years to make his money stand. From the implication of the LCH theory, my life income saving/spending experience truly reflects the LCH theory in practice. My elementary and high school and my father’s anticipated retirement spending communicate the importance of LCH implications to decision-making. The LCH theory holds positively in that a person’s decision to consume and save dramatically depends on the future possibility of income/earnings.

Conclusion

Finally, it can be concluded that the Life-Cycle Permanent Income Model is crucial to every individual when making consumption and saving decisions. Although life is uncertain, wise decisions are important since they take one from one point to another. With poor income decisions, one can stagnate for a lifetime. As such, LCH theory helps individuals across the world to make decisions concerning consumption and saving, considering future income potential and capabilities.

References

Econ. (2014). Life Cycle – Permanent Income Model. Web.

Gomes, F. (2020). Portfolio choice over the life cycle: A survey. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 12(1), 277–304. Web.

Kindermann, F., & Krueger, D. (2022). High marginal tax rates on the top 1 percent? Lessons from a Life-Cycle Model with idiosyncratic income risk. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 14(2), 319–366. Web.

Permanent income hypothesis, a two-period application [PowerPoint slides] (n.d.).

Sonderegger, T., Berger, M., Alvarenga, R., Bach, V., Cimprich, A., Dewulf, J., Frischknecht, R., Guinée, J., Helbig, C., Huppertz, T., Jolliet, O., Motoshita, M., Northey, S., Rugani, B., Schrijvers, D., Schulze, R., Sonnemann, G., Valero, A., Weidema, B. P., & Young, S. B. (2020). Mineral resources in life cycle impact assessment—part I: a critical review of existing methods. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 25(4), 784–797. Web.