Introduction

The Gilded Age was a time in American history characterized by dynamic economic growth, technological progress, widening income gap, and social and political turbulence. Despite the period’s association with economic expansion, it also saw considerable financial instability and multiple recessions that exacerbated the turmoil in other areas of society. Perhaps the most significant among those contractions was the Long Depression, which lasted from October 1873 to March 1879 – longer than any other recession in American history to date (National Bureau of Economic Research). Those years saw a sustained deflation, thousands of business bankruptcies, and unprecedented unemployment. The recession put a dent into the railway boom that was the primary driver of the Gilded Age economy. The Long Depression was influenced by long-term deflationary trends in America and abroad, but the specific event that launched it was the Panic of 1873. The crisis started in September of that year, when several leading banks collapsed due to a bank run, precipitating a chain of business failures throughout the country.

The Panic of 1873

Causes and Consequences

Even before the crisis commenced in earnest, several long-term factors were pushing the economy towards recession. Numerous technological and financial innovations led to a rapid increase in production in both Europe and the United States, which in turn caused a drop in prices and worldwide economic instability (Johannessen 91). In the United States, this growth was driven in no small extent by mass railroad expansion, which influenced virtually all areas of the economy (Siegler 157). The railroads attracted substantial investment from financial institutions, spurring innovation among them while supporting commercial development throughout the country through improved communications and infrastructure.

Additionally, the American economy was being hindered by the consequences of the Civil War, including the temporary abandonment of the pre-war bimetallic standard in favor of a fiat currency commonly referred to as the greenback (White 183). Wishing to resolve the currency uncertainty by asserting a gold standard, the Grant Administration committed to a deflationary monetary policy, issuing money at a lower rate than the real output. The 1873 Coinage Act officially demonetized silver in response to a dramatic fall in its value after the adoption of the gold standard by many countries in Europe (White 264). While this policy enabled an eventual strengthening of the currency, it also contributed to the deflation, progressively depriving investors of much-needed capital during a period of intense growth.

This predicament directly contributed to the fall of Jay Cooke & Company, one of America’s most highly regarded banks and the exclusive bond agent of the ambitious Northern Pacific Railway. Unable to attract enough investors to the project, the owner of the bank shifted its funds to cover the shortfall, leaving it incapable of meeting its obligations before depositors (Davies 161). The sudden bankruptcy of a trusted institution led to a general loss of confidence, the collapse of several other banks, and a ten-day closure of the New York Stock Exchange (Nitschke 232). Over 5,000 businesses faced bankruptcy in 1873 alone, most of them after October; by the peak of the depression, the number of annual business bankruptcies would exceed 10,000 (White 264). The panic in New York also escalated a nascent global recession that soon rebounded on America’s economy.

It can be seen that deflation was the primary component of this contraction. On top of the government’s deflationary policy, the collapse of so many banks and the chilling effect faced by others led to a drop in investment and lending, which further limited the money supply. As asserted by the Fisher Equation (MV=PT, where M=money supply, V=velocity of circulation, P=average price, and T=volume of transactions), the drop in money supply directly contributed to a fall in prices. The drastic increase in deflation increased the value of debts and redistributed wealth away from producers.

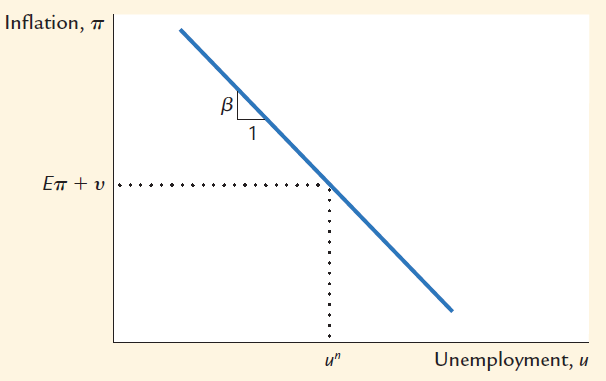

Furthermore, as implied by the Phillips curve (Figure 1), which establishes an inverse relationship between the rate of inflation and employment, deflation encouraged unemployment – at least in the short term. A sharp increase in unemployment meant a loss of income and production, as well as the deterioration of human capital made worse by an explosion in homelessness and malnutrition (White 268). A vicious cycle of reduced economic activity thus contributed to the span of the depression.

Impact of the Long Depression

The recession arrived when America was halfway through its transition from a predominantly agrarian economy to an industrial one. As of 1870, some 50% of the workforce was employed in agriculture, but urbanization and industrialization were advancing quickly (Siegler 171). Railroads and the investment they attracted contributed immensely to both processes, while also speeding up the commercialization of agriculture. The untimely suspension of the railway boom thus had a chilling effect on every area of the economy, while leaving numerous newcomers in cities cut off from their usual support networks.

It is interesting to note that despite the well-documented contraction, overall productivity was not so strongly affected. The latest estimates of real GDP per capita from the years of the Long Depression suggest that growth continued with few interruptions aside from a significant dip in 1874 (see Figure 2). This discrepancy can be explained in large part by the continued rapid pace of technological innovation (Baslé 14). On top of that, agrarian and industrial producers wishing to remain in business had no choice but to scale up production at lower prices (White 267). As a result, productivity could keep improving, albeit at a slower rate, while profits continued to decline.

The Long Depression had a disparate impact on different regions and groups. In regional terms, despite the crisis starting in the East, the wealth redistribution caused by deflation impacted most heavily on the West and South (White 369). The West was still being settled, and the South was going through an already arduous post-war economic reconstruction, so those regions tended to be debtors rather than creditors. The abandonment of essential infrastructure projects similarly hurt both regions. Conversely, those Eastern banks that survived the initial panic, such as the commercial banks of New England, were in an excellent position to wait out the crisis (Hilt 1). Bank affiliations were instrumental in keeping many non-financial corporations in the East afloat.

Farmers throughout the country were particularly profoundly affected by the fall in prices, making it a lasting cause of discontent. Recently freed slaves were even more adversely affected than most producers due to the collapse of the vital Freedman’s Savings Bank (White 266). Workers who remained employed suffered from a fall in wages, and in some cases, were forced to accept payment in scrip, which was not always redeemed later (Thies 24). Unsurprisingly, the fall in wages led to an increase in labor unrest, including America’s first nationwide strike – the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Deepening inequality caused political instability and disorder, which in turn damaged business confidence.

Large-scale unemployment posed a particular social problem during this crisis due to its unprecedented nature. The unemployment rate rose steadily during the depression, peaking at around 8.25% in 1878 (see Figure 3). Neither the authorities nor the workers themselves were prepared to deal with this new reality. The social safety net consisting primarily of charities, churches, and voluntary associations proved largely inadequate for their needs. The unemployed preferred to seek out help from relatives or go into debt, but neither solution was as effective in a prolonged recession (White 268). A large urban underclass emerged that relied on soup kitchens for their nutrition (Gordon 68). While the average consumer may have benefited from lower prices, those who were struck hardest by the crisis saw their living standards decline drastically.

The crisis caught the government off guard, escalating existing divisions within the ruling Republican Party between hard money (pro-deflation) and soft money (pro-inflation) factions. Doubling down on the deflationary policy, President Grant vetoed an 1874 bill that would have increased the money supply by 64 million dollars (White 274). His successor, President Hayes, similarly vetoed an 1878 bill that restored silver as a legal tender, though he was overruled by Congress (White 370). The government also attempted to protect jobs through high tariffs, which drove up costs for consumers and discouraged trade, especially as similar policies were adopted in European countries (Johannessen 92). While the government’s decisions allowed America to return to a de facto gold standard in 1879, the immediate effect of those policies was to prolong and deepen the crisis.

End of the Depression and Governmental Alternatives

Recovery began in 1878, as railroad and construction projects surged, and unemployment fell. This revival was partly attributable to global trends, as the runaway deflation in Europe had ceased by 1876 (Johannessen 105). Returning to the gold standard made the dollar more competitive on the world stage and helped restore confidence (Mollick 104). With the end of the contraction, continued gains in productivity contributed to an overall economic recovery. However, hopes that the gold standard would bring about a period of stable growth were not vindicated by subsequent events. Several more banking panics and recessions followed over the next few decades, including the Panic of 1893, which matched that of 1873 in severity (Gorton and Tallman 13). This outcome suggests that the fundamental problems of a high-growth deflationary economy were not solved.

With the benefit of hindsight, it may have been wiser for the government to pursue a different set of solutions. Consistently increasing the money supply and lowering tariffs from the start could have contained the long-term socioeconomic damage from the recession by shoring up the majority’s finances while encouraging business activity. If successful, such measures might have created a substantially more stable and less fragile economy for the rest of the 19th century, offsetting the disadvantages of inflation.

Conclusion

The problem underlying the Panic of 1873 and the Long Depression was a combination of deflation and rapid growth brought on by technological advances. While businesses were tempted to engage in ambitious ventures, they lacked the funds to do so without endangering the financial system. A series of bank failures caused by financial overstretch led to general prolonged depression and widespread unemployment, which led to numerous long-term social problems. The American government’s deflationary policies, while successful in strengthening the dollar by returning to the gold standard, exacerbated the issue further. Although the depression finally ended in 1879, economic instability remained a defining trait of the Gilded Age and resurfaced in a series of subsequent economic crises. Abandoning a rigid insistence on deflationary and protectionist policies may have softened the impact of the original crisis and created a more healthy economy.

Works Cited

Baslé, Maurice. “Mistaking a Phase of Endogenous Growth with a New Role for the State for a “Great Depression”: the Recent Financial Crisis Compared to that of 1873–1879.” Business Cycles in Economic Thought, edited by Alain Alcouffe et al., Routledge, 2017, pp. 27-41.

Bolt, Jutta, et al. “Maddison Project Database, Version 2018.” Rebasing ‘Maddison’: New Income Comparisons and the Shape of Long-Run Economic Development, Maddison Project Working Paper 10, 2018.

Davies, Hannah Catherine. “Spreading Fear, Communicating Trust: Writing Letters and Telegrams during the Panic of 1873.” History and Technology 32, no. 2, 2016, pp. 159-177.

Gordon, Robert J. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living since the Civil War. Princeton University Press, 2016.

Gorton, Gary, and Ellis W. Tallman. “How Did Pre-Fed Banking Panics End?” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016. Working paper. Web.

Hilt, Eric. Banks, Insider Connections, and Industrialization in New England: Evidence from the Panic of 1873. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018. Working paper. Web.

Johannessen, Jon-Arild. Innovations Lead to Economic Crises. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. Macroeconomics. Worth Publishers, 2016.

Mollick, Andre Varella. “Adoption of the Gold Standard and Real Exchange Rates in the Core and Periphery, 1870–1913.” International Finance 19, no. 1, 2016, pp. 89-107.

National Bureau of Economic Research. “US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.” National Bureau of Economic Research. 2020. Web.

Nitschke, Christoph. “Theory and History of Financial Crises: Explaining the Panic of 1873.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17, no. 2, 2018, pp. 221-240.

Siegler, Mark V. An Economic History of the United States: Connecting the Present with the Past. Springer, 2016.

Thies, Clifford F. “Samuel J. Tilden, Iron Money and the Election of 1876.” Public Choice Analyses of American Economic History, edited by Joshua Hall and Marcus Witcher, Springer, 2019. pp. 21-29.

Vernon, J.R., 1994. Unemployment Rates in Postbellum America: 1869–1899. Journal of Macroeconomics, 16, no. 4, pp. 701-714.

White, Richard. The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896. Oxford University Press, 2017.