Introduction

Background to the Study

There is a consensus among economists and academicians that a new wave of economic revolution is happening as countries position themselves to exploit opportunities created by rapid technological advancements in business (Brunet-Thornton & Martinez, 2018; Lardy, 2019). Countries with advanced economies, such as the United States (US) and Germany, are already poised to be leaders in this next phase of tech-based economic revolution because they are pioneers in the global Information Communications Technology (ICT) space (Oberheitmann et al., 2020). Germany has its Industry 4.0 plan, which seeks to integrate the Internet of Things (IoT) and Internet of Services (IoS) capabilities in its manufacturing processes to remain competitive (Matt et al., 2020). Comparatively, the US has introduced the Industrial Internet Platform (IIP), which champions an America-centric approach to economic development (Kheng, 2021). Indeed, it seeks to promote American interests in global trade as new competitors emerge and wrestle for global dominance. At the same time, Singapore has introduced the “Smart Nation” economic blueprint, while the United Kingdom (UK), in collaboration with its European partners, has also developed the “Factory of the Future” economic blueprint to compete with its western peers (Kheng, 2021). The development of these above-mentioned economic blueprints suggests that the global economic system is about to pivot from an era characterized by mass production to a new one defined by the adoption of smart and efficient production processes.

Major differences between the current and future economic models are expected. The new model is expected to be characterized by low-volume operations and the development of customer-centric products and services (Lardy, 2019), while the current system is based on the production of high volume goods and services. To implement the new system, countries are encouraging the deployment of smart production technologies, use of intelligent machines and the powerful data analytical programs to carry out production functions (Oberheitmann et al., 2020). Experts estimate that this trend is likely to add between $10 trillion to $15 trillion dollars to the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) when a majority of companies adopt ICT in their economic models (Kheng, 2021). To this end, various national visions of economic transformation aim to streamline their industries to reap the benefits of this anticipated change.

In 2015, under the leadership of Premier Li, the Chinese government introduced a plan to modernize the country’s economy by the year 2025 (Economy, 2018). A government policy known as “Made in China 2025” was the product and it is aimed at securing the position of the People’s Republic of China as a global economic powerhouse by encouraging investments in domestic technologies to compete with advanced countries, such as the United States (US) and Germany (Economy, 2018). Its goals align with a commitment to reduce the nation’s reliance on foreign technology by nurturing domestic capabilities, especially in impactful sectors of ICT, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and 5G (Tong & Wan, 2017). At a high level of economic planning, the existence of the “Made in China 2025” blueprint means that the government is looking to exploit future economic opportunities by enhancing China’s competitiveness in the global economy. Consequently, the development of the country’s industrial sector, through ICT adoption, has become one of the priority areas for the government.

The Chinese government sees the “Made in China 2025” vision as its best roadmap to integrate its economy into the global system, thereby allowing it to cooperate with advanced economies that primarily dominate this market (Tong & Wan, 2017). Essentially, the “Made in China 2025” plan is designed to move China from a low-cost manufacturing economy to one of the most advanced in the globe (Cheng et al., 2021). The success of the concept is rooted in three key pillars. The first one is the elimination of all obstructions preventing the seamless flow of technology from developed nations to China (Tong & Wan, 2017). The second goal of the economic plan is strengthening China’s position as a global manufacturing hub by strengthening its accountability standards to attract more foreign investments (Cheng et al., 2021). However, given that new entrants in the global manufacturing sector, such as Vietnam and Cambodia, are competing for the same space, China is expecting to join advanced economies in becoming an advanced economy (Ling, 2017). Alternatively, the government’s “Made in China 2025” plan involves simplifying administrative procedures that undermine the completion of business contracts agreements in the country (Cheng et al., 2021). This plan is aimed at simplifying business processes, especially for foreign companies intending to do business in China.

The “Made in China 2025” plan is elaborate and expected to be complete after the completion of three phases. The first one is set to run until 2025 and its milestone is China’s full entry into the ranks of strong industrialized nations (Cheng et al., 2021). The second phase of the economic blueprint is expected to be completed in 2035 and will be characterized by the attainment of a mean level of production that is similar to those of advanced nations (Li & Pogodin, 2019). The third stage should be complete in 2049, at the 100-year anniversary of the plan, and will be characterized by China’s ascent as the world’s dominant global manufacturing hub (Li & Pogodin, 2019). Therefore, based on the ambitious nature of this economic plan, the “Made in China 2025” blueprint is a government-based economic policy for the advancement of the Chinese economy.

Research Problem

The government of China introduced a raft of measures to protect its economy from the ravaging effects of the COVID pandemic but it is yet to be established whether these techniques have been successful, or not. If unsuccessful, the Chinese economy would be negatively affected because SMEs will be unable to recover on time and play their role in supporting the economy (Ertel, 2021). However, if they succeed, the role of the SME sector in supporting the country’s economic growth will be cemented (Wang et al., 2020). Currently, the impact of government intervention on SME development is still unclear.

The Chinese Premier recently acknowledged that the restart of the Chinese SME sector is important to the recovery of the economy (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020; Lardy, 2019). However, statistics show that up to 60% of SMEs that closed down due to the pandemic have not reopened, while 95% of major corporations have done so (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). The Premier further admitted that if the economic system collapses, a domino effect will be realized and many sectors of the economy will be negatively affected (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). Analysts predict that the labor market would be the first to feel the effects because people would be unable to keep their jobs (Wang et al., 2020). Additionally, those who can hold on to theirs will be unable to meet their credit and financial obligations due to economic underperformance, thereby creating a knock-on effect on other sectors of the economy. Indeed, if people are unable to pay their mortgages, their homes may be auctioned, thereby increasing the probability of witnessing a banking collapse (Su et al., 2020). These statements mean that the collapse of the SME sector could have far-reaching implications on the social, economic, and political life of China.

The Chinese SME sector remains fragile and vulnerable in a post-COVID world but the government continues to invest many of its resources towards supporting large multinationals mostly because of their significant contribution to the country’s GDP (Wang et al., 2020). However, the GDP of China is equally dependent on the success of the SME sector, meaning that they also need government support in the same manner as multinationals do. Statistics that support this statement suggest that up to 85% of Chinese SMEs could be bankrupt in three months due to the ravaging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic if they do not receive government support (Wang et al., 2020). Some of the worst affected sectors of the economy have taken significant hits from the pandemic. For example, the catering industry in China has contracted by more than 45% since the outbreak started (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). The negative outcomes reported in this sector are an indicator of the struggles that Chinese SMEs are experiencing in today’s volatile business environment (Su et al., 2020). A 30% drop in the number of new business registrations in China further highlights this problem (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). These statistics only highlight the effects of the pandemic on registered SMEs; unregistered ones could have been worse affected by the pandemic. Unlike giant multinationals that have sufficient cash reserves to protect themselves from the ravages of COVID-19, SMEs have insufficient insulation from unforeseen economic shocks (Su et al., 2020). Therefore, they remain volatile and unstable in a business environment characterized by uncertainties.

The slow pace of recovery for the SME sector highlights challenges that firms are experiencing today. Given the implications of “Made in China 2025” on the Chinese economy, the recovery of the SME sector cannot be overstated. This is because about 50% of all cash revenues collected by the Chinese government come from the sector (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). At the same time, SMEs account for 80% of jobs in China (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). In this regard, the industry is a catalyst of the country’s economy and one of the key growth drivers for the growing Chinese Middle Class. Therefore, if a large-scale liquidation event happens because of the environment created by the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy of China could be negatively affected through job cuts and SME collapses, thereby affecting millions of livelihoods.

Research Aim

The aim of this investigation is to understand the implications of the “Made in China 2025” concept on the performance of SMEs in China. The findings of this investigation are expected to be relevant to a post-COVID world, thereby necessitating the importance of understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected SME performance vis-à-vis the implications of “Made in China 2025” on the economy. The research objectives are as follows:

Research Objectives

Four objectives guide this investigation. They are aimed at understanding the implications of “Made in China 2025” on the growth and integration of SMEs into the global manufacturing system and to identify opportunities that the COVID-19 pandemic poses to SMEs as listed below.

- To understand how the “Made it in China 2025” concept has affected the growth and development of SMEs in China

- To compare China’s “Made it in China 2025” and Germany’s Industry 4.0 economic plans

- To estimate the impact that the “Made it in China 2025” concept has had on the integration of SMEs into the global manufacturing system

- To identify opportunities that the COVID-19 pandemic poses to the adoption of “Made in China 2025” concept in the Chinese SME sector

Research Questions

- How has the “Made it in China 2025” concept affected the growth and development of SMEs?

- How do the “Made it in China 2025” and Industry 4.0 concepts compare?

- What impact has the “Made it in China 2025” concept had on the integration of SMEs into the global manufacturing system?

- What opportunities will the Covid-19 pandemic pose to the adoption of “Made in China 2025” concept on the Chinese SME sector?

Significance of Study

As highlighted in this paper, countries are positioning themselves in the global marketplace to exploit new models of economic development (Wang & Chebo, 2021). The next wave of economic growth is expected to be characterized by technological advancements in different ICT fields, such as AI, machine learning, and the growth and development of the 5G network (Flyverbom et al., 2019). From this background, countries are investing in the development of new strategies for industrialization to exploit opportunities that may emerge from the technological change described above. Motivated by the actions of their developed counterparts, developing and emerging economies are hastening their industrialization processes and perfecting their developmental plans to also exploit opportunities that are associated with the new wave of technological development.

This study will be critical in developing competitive advantages across nations based on the role played by technological advancements in improving their competitive positions. Relative to this statement, the United Nations (2020) says that a country’s technocrats engineer the prosperity of a nation. Therefore, economic modeling is important in securing the developmental objectives of a country. In the context of this investigation, the competitiveness of a country is based on its pace of innovation and adoption of new technologies. The growing competition for economic dominance that exists among nations affirms the importance of country-specific policy initiatives to develop the global economy because most nations are engaged in processes that are set to improve their domestic competitiveness, which is akin to global competitiveness (Alexandru-Mircea & Marilena-Oana, 2018). These processes are described by the creation and retention of new knowledge, while competitive advantages are sustained through the development of highly localized processes. However, variations in national culture, ability to absorb new technology, and human capital requirements play a critical role in determining a nation’s competitiveness.

Structure of Paper

This paper has five key chapters outlining different stages of data collection, analysis, and presentation of findings. The first chapter presents the background of the research topic, including the aim and objectives that are to be fulfilled at the end of the investigation. The second chapter contains a review of the extant literature to understand the current state of research on the subject area. The third chapter will be the methodology section, which contains the justification for selecting different research approaches. These details will form the basis for the development of chapter four of the study, which will be a presentation of the findings. Key insights generated from the current review will be detailed in this section of the paper and the main findings summarized in the fifth chapter of the study, which is the conclusion section that also contains recommendations of the study.

Literature Review

This chapter is an analysis of extant literature on the present subject area. Key sections of this chapter explore existing knowledge that discusses the “Made in China 2025” plan, vis-à-vis other economic models pursued by other countries. In this regard, the main areas discussed in this chapter include conditions for the establishment of the “Made in China 2025” plan, its priority areas, how it compares with other existing models, and the moderating role that the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the performance of the SME sector. However, before delving into the details of this analysis, it is first, important to understand the contextual factors affecting the performance of emerging economies in the current economic environment.

Trajectory of Economic Development for Emerging Economies

The science of economic management is at the center of the quest for improved economic performance by many emerging economies. The adoption of new technologies and the re-evaluation of industrial structures are common strategies adopted by organizations to realize improved economic performance in the nations (Ligang et al., 2019). However, for many developing countries, the same plan cannot be copied because most governments are focused on promoting sustainable development, which is a complex idea that has to be balanced against present and future needs of development (United Nations, 2020). Research studies suggest that the adoption of sustainable development is similar to a shift from a quantitative to qualitative understanding of economic development and management (Cheng et al., 2021). The integration of ICT in economic management follows this path of analysis.

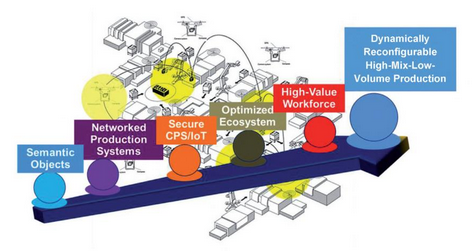

In the past decade, the adoption of technology-based tools in promoting economic development has happened due to the combination of digital and non-digital products and services in manufacturing (Ligang et al., 2019). The service industry is one area where technology has been deeply integrated with real-life business problems to create better systems of service delivery. This has happened through increased rates of information exchange, high levels of coordination across departments, and the enhancement of processing speeds (Cheng et al., 2021). In this regard, technology emerges as an important tool for saving resources and promoting sustainable development in an economy. In this regard, most emerging economies have to contend with the need to evaluate different economic variables to find the right balance to cope with the demand for a high-mix-low-volume production model, which is central to the realization of lean manufacturing systems (Mittal et al., 2019). Figure 2.1 below shows different elements that have to be included in this plan.

The diagram above shows different factors that an emerging economy has to consider when developing their economic plans. They include aspects of networked production systems, semantic objects, IoT, optimized ecosystem, high-value workforce, and the development of a reconfigurable high-mix-low-volume production model (Kheng, 2021).

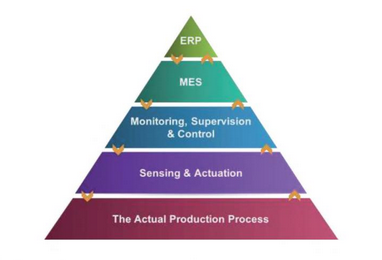

The current manufacturing system used by many emerging economies is characterized by highly reconfigurable systems that operate at the product process level (Zheng & Ming, 2017). This has been made possible through improvements on business process engineering activities, which have reconfigured system processes across various levels of production (Zheng & Ming, 2017). For example, under this plan, the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) technique has been improved to include resource planning and operational management activities through an elaborate and interlinked system of production aimed at promoting efficiency (Kheng, 2021). Production systems, which are designed to handle dispatch issues and scheduling arrangements, support manufacturing execution functions have been enhanced in the same manner (Kheng, 2021). Monitoring and execution functions of the manufacturing process have been deployed to enhance real-time processes as well. Sensory and actuation functions are also engaged in the use of sensory data to optimize production processes (Kheng, 2021). The final layer of the production system is defined by systems where the actual production process happens, as highlighted in figure 2.2 below.

Based on the structure of the above-mentioned pyramid, although different traditional production processes operate in an interlinked fashion, most of them work in silos – meaning that there is minimal levels of coordination across different business divisions. Smart manufacturing strives to improve interconnectivity among these independently working silos to create better synchrony of production processes (Zheng & Ming, 2017). This process involves the inclusion of artificial intelligence and IoT capabilities to support the transition. However, some legacy systems may need to be maintained throughout transformation phase to support the entire transition given that not everything needs replacement in the transition to smart manufacturing (Kheng, 2021). It is projected that the use of the right cyber connectivity tools could help address the problem. The government of China conceptualized the “Made in China 2025” plan under these conditions. They are further explained below.

Conditions for the Establishment of “Made in China 2025” Plan

As highlighted above, emerging economies have to contend with unique challenges in modernizing their economies to become competitive in a fast-paced technological world. Particularly, this statement is true for China, which has already experienced much of the economic transformation that low-income nations yearn for but is yet to overcome the last hurdle towards becoming an advanced economy. This section of the review shows that two critical areas are important drivers for the transformation and the development of the “Made in China 2025” plan – reforming industrial systems and demographic changes in China. They are further explained below.

Reforming Industrial Systems

The collapse of the global financial system during the 2007/2008 economic crisis heralded a period where countries had to reevaluate their economic models to make them more resilient and responsive to macroeconomic shocks (Oberheitmann et al., 2020). Some of these nations re-launched their industrialization plans. For example, several countries in Europe adopted similar measures, while the US struggled with tackling domestic economic challenges, such as its ageing infrastructure (Alexandru-Mircea & Marilena-Oana, 2018). The biggest crisis to have affected Europe, since the 2007/2008 crisis, has been “BREXIT,” which refers to the exit of the UK from the European Union (EU) economic bloc. This one change meant that the European economy would become fragmented when different nations hold varied economic goals (Brunet-Thornton & Martinez, 2018). Coupled with the entry of immigrants into some EU countries, such as Germany, the grounds for the development of a complex EU economic integration plan have been created.

In the US, the trade conflict with China is one of the most impactful forces to have affected relations between both countries (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Particularly, the quest by the US to pursue trade protectionism policies and disputes over currency exchange rates has undermined confidence in trade between the once cordial trade partners (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). These issues have created conditions for China to look for locally developed technological solutions for its rapidly growing economic enterprise because, based on the actions of the US, its foreign partners are becoming unreliable (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). From this background, the “Made in China 2025” plan was conceptualized.

China has invested many resources in reforming its industrial systems to make it the global manufacturing powerhouse that it is intended to be according to the “Made in China 2025” plan (Ligang et al., 2019). Particularly, there have been many investments made in expanding the country’s production capacities to become more competitive (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). However, if China’s manufacturing capacity is compared to those from other advanced nations, it appears less competitive. At the same time, China is experiencing significant challenges sustaining its traditional low-cost production model because of increased labor costs, an imbalance between its demand and supply of raw material, changes in global supply systems, and trade disputes with its international partners (Ligang et al., 2019). These challenges are making it more difficult for China to maintain a high rate of economic development that would enable it to compete with its industrialized partners. Additionally, most South Asian countries are replicating the successful low-cost Chinese economic model, thereby becoming substitute-manufacturing hubs (Alexandru-Mircea & Marilena-Oana, 2018). The effect is that China’s competitiveness in the Asian manufacturing sector is being undermined. These macroeconomic changes created the impetus for the development of the “Made in China 2025” plan.

Demographic Changes in China

Unlike other economies around the world, China’s population and its internal demographic characteristics have to be factored in economic and policy decisions. This is because the country is home to more than one billion people, which comprises of about 1/7 of the global population (Xinxin et al., 2016). Given that the US and other leading industrialized nations do not have the same number of people in their countries, the potential to flip the large Chinese population into a formidable market is attractive to policy developers who conceptualized the “Made in China 2025” plan (Tong & Wan, 2017). There is precedent in understanding the impact that the Chinese population could have on markets and policy success because the current status of the Chinese economy as the world’s manufacturing center is partly informed by the country’s ability to provide low-cost labor from its massive population (Economy, 2018). This ability has turned out to be its main competitive edge in the global manufacturing space because several multinationals have relocated their production processes to China to exploit the demographic potential that exists in the region.

The consequence of integrating the large population of China into its economic system has led to the development of rapid socioeconomic changes across different cadres of the society (Xinxin et al., 2016). However, most of these changes have led to the development of an abrupt socioeconomic re-stratification of the people that has been characterized by the elevation of a large population of nationals from low to middle-income economic status (Xinxin et al., 2016). This change in economic fortunes has led to rapid demographic shifts because few people are willing to avail their labor cheaply, as was the case before (Tong & Wan, 2017). This statement explains part of the reason why “Made in China 2025” was formed to align with China’s readiness to advance its competitiveness in the global manufacturing sector. It also explains why the government is now focused on making the economy more technology-intensive as opposed to labor-intensive, as was the case before.

Broadly, the “Made in China 2025” blueprint seeks to address most of the socioeconomic challenges that have arisen because of China’s improved economic status. One of the ways it intends to address this issue is through the redistribution of profits to make it easier for segments of the population that have not experienced the benefits of economic development to do so (Economy, 2018). The blueprint contains several strategies for doing so, including instituting structural reforms, embracing innovation, promoting the development of the countryside, and promoting the Belt and Road initiative (Tong & Wan, 2017). These plans have been used to identify key priority areas as described below.

Priority Development Areas for “Made in China 2025”

The “Made in China 2025” plan identifies various priority areas of development that should support the overall vision to make China an advanced economy. Updating energy conservation technologies in the automotive industry, promoting the development of New Generation Information Technology Industry (NGITI) to improve supply-side economics of production, modernizing aerospace technology, promoting innovation in shipbuilding, and updating railway transport technologies are some priority areas identified in this review that would highlight the core tenets of the “Made in China 2025” plan. They are discussed below.

New Generation Information Technology Industry (NGITI)

New Generation Information Technology (NGITI) is one of the core pillars of the “Made in China 2025” plan. NGITI refers to the use of advanced technological tools, such as integrated circuits and operating system software, to create a new infrastructure for guiding China’s economic activities (Li & Pogodin, 2019). This plan has been designed to reform the structural supply-side economics of the Chinese manufacturing industry and aid in the production of quality products (Li & Pogodin, 2019). The Communist Party of China and the State Council are aggressively pushing for the completion of structural changes aimed at making the NGITI a success (Li & Pogodin, 2019). Their focus has mainly been on the fields of cloud computing and big data management, using AI and web-based tools (Grau & Wang, 2020). Based on its intensity and level of technological innovation, the NGITI part of the “Made in China 2025” plan has become an essential part of the development of a sustainable model for the economic blueprint, which also considers the environmental sustainability of its proposed strategies. By venturing into other spheres and industries, the NGITI plan facilitates knowledge transfer across different economic sectors in China and improves efficiency to develop quality products across the board (Cheng et al., 2021). In line with the vision to make China’s economy more sustainable, NGITI is regarded as a tool for promoting sustainable development in the overall plan.

Unlike other technology-based solutions integrated into the “Made in China 2025 plan,” NGITI not only emerges as a technology tool but a transitional development model for gathering, analyzing, and disseminating data (Li & Pogodin, 2019). It is associated with increased opportunities for reforming the Chinese economy and a tool for providing technical support in case a problem emerges (Grau & Wang, 2020). These benefits can be transferred to several industries and their subsectors through a complex open web-based model that integrates industry functions across business divisions (Cheng et al., 2021). Using a complex network system, resource allocation in China is likely to be rebalanced because NGITI is designed to affect different processes supporting local industries, such as marketing, accounting, total quality management, research and development (Cheng et al., 2021). Given that NGITI’s reach can transcend different fields, the boundary separating production functions across different industries and product categories can be overlooked (Grau & Wang, 2020). However, researchers suggest that there are positive outcomes to be realized at the end of the process, including increased resource allocation priorities, upgraded system processes, and advanced levels of adopting sustainable development concepts (Cheng et al., 2021). Overall, NGITI is designed to address some of the systemic weaknesses affecting the Chinese manufacturing sector. Particularly, it is associated with heightened levels of information exchange and improved technological adoption (Grau & Wang, 2020) within the “Made in China 2025” plan. The vision underpinning this change is rooted in the quest to use intelligent production systems to promote sustainable development.

Modernizing Aerospace Equipment and Technology

Under the “Made in China 2025” plan, the Chinese government intends to have its commercial airline companies to supply at least 10% of the domestic market and 20% of the global market requirements by the year 2025 (Lee, 2018). This goal is formulated against the backdrop of China’s outdated technology because experts estimate that the technology used in the Chinese aerospace sector is 20 years behind current trends (Lee, 2018). Under the “Made in China 2025 plan,” the government expects to build local capacity to make its aircrafts (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021). This move is intended to disentangle the Chinese government from the geopolitical and economic implications of buying aircrafts from the current duopoly that exists in the market, which is characterized by the activities of two companies – Boeing and Airbus (Lee, 2018). Given that both companies are western-based, Beijing understands that improving its local ability to make aircrafts could disentangle China from the yolk of negotiating with western companies to support its domestic enterprises (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021). Under these conditions, China is also aware that its aviation market is poised to overtake that of the US by the year 2022 (Lee, 2018). Researchers estimate that the sector would need about 7,000 aircrafts in the next two decades and there is an opportunity therein to fill this demand domestically (Lee, 2018). Therefore, it sees investments made in the aviation sector as a tool to facilitate and benefit from this change

High Technology Shipbuilding

The “Made in China 2025” vision is relevant to China’s blue economy. The country’s ship building industry is regarded as one of the best in the world and accounts for about 90% of it output (Global Security, 2020). The Chinese government intends to support about 71 ship builders who operate different yards (Global Security, 2020) under the “Made in China 2025” plan. It intends to do so through policy interventions, such as “The Plan on the Adjustment and Revitalization of the Shipbuilding Industry,” which was intended to address three critical areas of management: (i) the fall in demand for shipping products, (ii) restructuring of business processes, and (iii) encouragement of domestic innovation (Global Security, 2020). The Chinese State Council is responsible for the implementation of these policies and it operates two state-owned shipbuilding companies – CSSC and CSIC (Global Security, 2020). Currently, the Chinese shipping industry is deemed to be affected by overcapacity issues (Global Security, 2020), but the focus of the “Made in China 2025” plan is to decrease this capacity by making it more efficient and adaptable to the needs of the market.

Advanced Railway Transport Technologies

The Chinese government, under the framework of the “Made in China 2025” plan, has affirmed its commitment to invest in innovative research and development activities to identify new technologies that would modernize the country’s railway transport system (Global Times, 2021). The Ministries of Transport, Science and Technology are on the forefront in spearheading this change (Global Times, 2021). Their main task has been to identify impediments to the adoption of new technologies and eliminate them for improved integration of high-tech equipment in the railway transport sector (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021). The current focus of the Chinese government in advancing current technology is to make new technologies more available to parties that need them and promote similar developments in related industries (Global Times, 2021). In the end, competencies can be synced to create synergies in production. Under the “Made in China 2025” plan, basic research into the development and adoption of new technology are expected to be strengthened by the year 2025. By 2035, innovation capabilities in the railway transport sector are also expected to be fully enhanced and cutting-edge technology integrated into the main railway transport network (Global Times, 2021). These changes are expected to enable China to meet its technological requirements of the railway transport network in the same manner, as any developed nation would do.

Energy Conservation Technologies in Automotive Industry

The Chinese automotive industry is part of the focus of development for the “Made in China 2025” plan because of the sector’s centrality to the Chinese economy. Given that the country is rapidly urbanizing, it is expected that there will be a sustained rise in the demand for automobiles in the short-term (Asia Pacific Energy, 2016). China intends to promote energy conservation as a core pillar of its innovative strategy in the automotive industry (Asia Pacific Energy, 2016). The adoption of new technology in the automobile sector is not only seen as a strategy to minimize pollution levels in the country but also a technique for promoting sustainable development in the automotive sector (Asia Pacific Energy, 2016). The “Made in China 2025” plan intends to highlight three key areas that will be influenced by the change.

The first one is adherence to a combination of industry changes and technological transformation. Under this plan, the automotive industry is expected to popularize the use of energy-saving vehicles while at the same time making energy savings on existing models (Asia Pacific Energy, 2016). Secondly, under the same plan, automotive companies are expected to be committed to openly collaborating with international partners to find cheaper and more effective ways of manufacturing cars (Asia Pacific Energy, 2016). The third strategy is designed to encourage local automotive companies to adhere to government regulation and adapt to market forces. The last strategy involves giving direct support to automotive companies and strengthening the performance of their associated businesses (Asia Pacific Energy, 2016). Following these strategies is projected to foster new growth opportunities in the automobile sector that would allow local companies to compete with their international partners effectively.

The breadth of the “Made in China 2025” plan also covers other priority areas of China’s economy, including electric power mechanic engineering, agricultural mechanical engineering, smart equipment adoption, deployment of numerical control machines in production, new materials development, and advances in biomedical equipment research (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021; Li & Pogodin, 2019). These core areas of research suggest that the Made in China blueprint is intricate and can be compared to other economic models as described below.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Small Businesses

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on most businesses. In the context of the SME sector, researchers pointed out that the pandemic caused breakages in supply chain linkages and created uncertainties in operational planning (Hemmington & Neill, 2021; Voigt, 2018), as described below.

Uncertainties in Operations Planning

The COVID-19 pandemic, which originated from China, has had far-reaching implications on SMEs because they tend to operate in industries, which were most vulnerable (Hemmington & Neill, 2021). According to Müller and Voigt (2018), a small business is an enterprise that has fewer than 50 workers. They also tend to have a limited geographical presence and have a relatively small market share of any industry, compared to multinationals or bigger organizations (Hemmington & Neill, 2021). These firms are also active in niche markets because they offer specialized products and services compared to multinational companies or other types of organizations that appeal to a larger market (Müller & Voigt, 2018). In most economies, SMEs supply important parts and components to many large organizations, thereby filling in the gaps present in supply chain linkages (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). Given that most large firms depend on small and medium enterprises to complement their operations, SMEs play an important role in the economic development of any country. Their main advantage is the flexibility in implementing business decisions because few players are involved in daily operations (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021; Li & Pogodin, 2019). Despite the suboptimal role played by these firms in contributing to the economic growth of a country, many of them are instrumental in the adoption and development of new technologies.

For most economies, the number of small businesses is higher than that of big businesses. Most SMEs also account for supply chain linkages that support a country’s economy (Müller & Voigt, 2018). Earlier studies on the performance and role of small businesses in the global economy show that their success is pegged on how well they are interlinked with national and global systems of operation (Zheng & Ming, 2017; Müller & Voigt, 2018). Current studies have shown that most businesses, which have an open sharing and knowledge utilization process, were better equipped to absorb new technologies and adopt open innovation systems (Hemmington & Neill, 2021). Studies have also shown that this attitude to innovation is directly linked with the performance and growth of the SME sector (Zheng & Ming, 2017; Müller & Voigt, 2018). Coupled with other examples, such as the poor performance of the retail sector, most small businesses worldwide were vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic.

Broken Supply Chain Linkages

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on businesses cannot be ignored when understanding the impact of institutionalized policies on businesses because of its sheer scope and effects on supply chain processes worldwide (Hemmington & Neill, 2021). In one study that explored the impact of the pandemic on the ability of small businesses to adopt innovation tools on open platforms, it was demonstrated that the pandemic had a neutral effect on their ability to procure and absorb new technologies (Ertel, 2021). The same study pointed out that revenues had not been significantly affected by the pandemic as initially believed (Ertel, 2021). This statement meant that businesses did not have to make significant alterations to their processes and operational designs. It further pointed out that many small businesses are equipped to thrive under conditions of uncertainty because most of their businesses are linked to business-business relationships and third party actors, thereby making it possible to weather such effects (Ertel, 2021). At the same time, it was reported that businesses, which were better internationally aligned than local counterparts, had an easier time overcoming the effects of the pandemic because they could deploy their vitality to manage complex risk management processes (Hemmington & Neill, 2021).

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, countries had to use technology to run their operations to prevent the complete shutdown of some industries or economic sectors. Many businesses have since adopted new methods of doing business from the crisis, such as the use of Zoom to carry out meetings (Hemmington & Neill, 2021). Such tools were survival toolkits for small businesses, without which they would have faced complete shutdown by authorities to avoid breaching COVID-19 regulations. Businesses that were considered essential to the survival of the economy were shielded from complete shutdown and allowed to operate under certain restrictions, such as applying the social distancing principle when serving customers (Hemmington & Neill, 2021). These examples show the critical role that technology played in facilitating the operations of small businesses. Without the pervasiveness of such technology, it is difficult to comprehend the cost that the pandemic would have had on small businesses.

Change in Business Concepts

Uncertainty in the business environment has led to transformations of business concepts from those that depend on the utilization of an organization’s internal resources to optimize production to those that rely on the use of resources out of the company’s scope of control to achieve the same objective. The latter approach is primarily focused on exploiting resource capabilities and market access options that are away from a country’s borders (Wang & Chebo, 2021). Open innovation processes can be summed as those that promote the acquisition of new technologies or knowledge for SMEs. For example, the development of collaborative networks across different business divisions and the use of networking options across various levels of product design have played a critical role in the deployment of open innovation tools for enhanced service and product delivery in many organizations (Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, the open innovation platform offers businesses an opportunity to exploit both internal and external techniques to achieve their business objectives by allowing them to acquire knowledge from different sources concurrently. The open innovation platform offers small businesses with an opportunity to use existing platforms of knowledge transfer to better their internal processes for maximum product and service delivery (Wang & Chebo, 2021). Given that few of them can manage this task independently, most SMEs have been forced to collaborate with other firms in this endeavor thereby giving them an opportunity to integrate with others in the global marketplace.

Summary

The findings of this study are segmented because they do not collectively explore the impact of the “Made in China 2025” economic blueprint on China’s economic performance. Instead, researchers have presented the evidence in silos, thereby making it difficult to make connections between the impacts of the “Made in China 2025” concept on the country’s economy. Furthermore, few researchers have focused on understanding the effects that the institutional policy would have on the SME sector in a post-pandemic economy. The present study aims to make these connections by integrating different aspects of the analysis to create a common understanding of the implications of the “Made in China 2025” policy on the SME sector in a post-pandemic society.

Methodology

The format for this chapter is borrowed from the works of Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill who suggest that research processes should be analyzed in six stages (Mahrool, 2020). They include a review of the preferred philosophy, approach, strategy, method, time horizon, data collection and analysis (Mahrool, 2020), as described below.

Research Philosophy

It is important to understand the philosophy underpinning a research because it highlights the set of principles from which the findings will be useful in contributing to a specific subject area. There are four main philosophical views used in research and they include pragmatism, realism, interpertivism, and positivism (Kumar, 2018). The positivism research philosophy assumes that knowledge is independent of the subject being studied but the interpretivism research approach assumes that the subject plays a role in understanding the findings (Kumar, 2018). Based on this definition, the interpretivism philosophy is commonly associated with qualitative studies, while the positivism research approach is linked with quantitative studies (Mahrool, 2020). For purposes of this investigation, the interpretivism philosophy was used in interpreting the data because the researcher relied on the mixed methods research approach to combine qualitative and quantitative elements of the investigation into one coherent narrative. In this context of review, the interpretivism research approach plays a critical role in understanding assumptions that the researcher made in selecting other tools of research as described below.

Research Approach

A research approach helps readers to understand the techniques used by an investigator in gathering data and analyzing its findings. The inductive and deductive techniques are the two most commonly cited research approaches (Mahrool, 2020). The deductive research approach investigates a research phenomenon from one predetermined hypothesis (Kumar, 2018). Comparatively, the inductive approach uses observations to develop a theory (Mahrool, 2020). Based on these differences, the researcher selected the inductive approach as the main technique for the study. This is because the theories proposed in the current investigation were developed from observations made in extant literature. Therefore, there was no preconceived theory relied on to guide the study at its inception.

Research Strategy

Research strategies describe techniques adopted by a researcher to carry out an investigation based on the type of desired data and practicality of realizing the research objectives. According to Kumar (2018) researchers can conduct, experimental, action, case study, interviews, surveys and systematic literature reviews when investigating a research phenomenon. The researcher used the systematic literature review technique for the current investigation because the evidence collected was from published research articles. This technique was also adopted in the study because of its national focus. In other words, it was difficult to conduct a primary investigation to understand the implications of the “Made in China 2025” state plan and COVID-19 pandemic on businesses due to logistical and resource limitations. Therefore, the systematic review method emerged as the most appropriate method to use for the current study.

Choice of Methods

According to Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, three methods are used in academic research studies – mono, mixed, and multi methods (Mahrool, 2020). As its name suggests, the mono method is focused on the use of one research technique. However, the mixed method is used when a researcher combines two or more techniques in an investigation (Mahrool, 2020). Alternatively, the multi-method involves a combination of various techniques to conduct a research investigation (Kumar, 2018). The researcher used the mixed method technique for the current investigation because it contains qualitative and quantitative aspects of research (Kumar, 2018). The exploratory nature of the topic also justifies the use of the mixed-method technique because relying on one type of data would be inadequate to cover the scope of the investigation. Furthermore, the “Made in China 2025” concept contains both qualitative and quantitative goals because it is designed to achieve quantifiable economic results while changing the fundamental ideology of leadership at the same time. Therefore, it can be argued that the formulation of the “Made in China 2025” vision is understood through qualitative reasoning, while its objectives are measurable using quantitative techniques.

Time Horizon

According to Mahrool (2020), the time horizon for a study refers to the model period used to collect evidence. In this regard, two techniques for understanding time horizon are proposed for use in academic studies and they include longitudinal and cross-sectional timeframes (Kumar, 2018). The cross-sectional model is commonly applied in research investigations analyzing a topic at a single point in time (Mahrool, 2020). Comparatively, the longitudinal method allows researchers to observe or investigate a research phenomenon for a long time, such as weeks, a month, or even years (Mahrool, 2020). The latter technique emerged as the appropriate fit for the current investigation because the scope of the study stretches for years. Stated differently, the aim of the study is to understand the implications of the “Made in China 2025” concept on the SME sector in a post-COVID environment, which is years away. At the same time, the “Made in China 2025” vision stretches for the same period. This means that its impact on businesses will be felt beyond 2025. Therefore, the longitudinal research framework was the best fit for the study.

Data Collection and Analysis

For purpose of data collection, the researcher used secondary as opposed to primary data to answer the research questions. Secondary data was obtained from published information sources, including books, journals, and credible websites. As mentioned in this chapter, these materials were collected within a mixed method framework where qualitative and quantitative pieces of evidence were mixed. Secondary research sources were obtained from several online databases, including “Sage,” “Emerald Insight,” “Springer Link,” and “Google Books.” Ten scientific articles were retrieved from The French Foundation for Management Education (FNEGE) and the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) lists of approved journals and the rest were selected from other databases. Keywords used in the search were “Made in China 2025,” “COVID-19,” “SMEs,” and “China.” Articles that were older than five years were excluded from the investigation because the researcher intended to get updated data. Comparatively, journal articles that had an impact factor of more than 5/10 were selected for the analysis, while those that had lower scores were given less priority. The aim of doing so was to find articles that were relevant and credible to the current investigation.

Research findings were analyzed using the thematic and coding method, which analyzes information by categorizing data into unique themes identifiable by a code. As highlighted by Braun and Clarke (2021), this method is applicable in research processes based on the completion of six key stages. The first one involves familiarization with research data, where quantitative and qualitative information were identified and categorized accordingly. The second stage of data analysis involved coding the research materials into unique categories based on their content and relevance to the research objectives (Braun & Clarke, 2021). These codes were later used to generate themes – a process, which characterized the third stage of the thematic and coding method. The fourth stage of data analysis involved an analysis of these themes to make sure that they are consistent with the objectives of the investigation. Each of the themes were named in the fifth stage of data analysis. The last stage of review involved writing the final write-up of the research paper.

Findings and Analysis

The effects of the “Made in China 2025” concept on the SME sector were conceptualized within three main objectives of the economic blueprint. The first one is the integration of operations between the modern and conventional aspects of the Chinese manufacturing sector, the second one involves upgrading and modernizing the managerial structure of SME enterprises in China, and the third objective centers on the development of Chinese-based industry standards (Matt et al., 2020). As highlighted in chapter three of this paper, the researcher analyzed materials using the thematic and coding method. Broadly, 31 articles were linked to each theme and the associated number of articles for each one of them highlighted in table 4.1 below

Table 4.1 Themes and number of associated articles (Source: Developed by Author)

Data relating to each of the themes are highlighted below.

Effects of “Made in China 2025” on Growth and Development of Chinese SMEs

In recent years, scholars have started to investigate the role of SMEs in actualizing national economic goals. Already, several researchers have explored the role of SMEs in implementing industry 4.0 (Matt et al., 2020), while a lower number of them have explored their role in the “Made in China 2025” concept. Most of the latter group of studies have been focused in Europe and highlight the role of the government in helping local enterprises to flourish. For example, through the “Horizon 2020,” program, the European Commission gave both direct and indirect support to local SMEs in their quest to adopt innovative techniques for production (Matt et al., 2020). The commission also supports the activities of SMEs by supporting the creation of an enabling environment for embracing new technologies. In China, the role of the “Made in China 2025” concept in supporting the growth and development of SMEs was categorized into three key areas, as shown below.

Improved Adaptability

Due to their flexibility, SMEs have proved to be more resilient and adaptable to economic crises than multinational organizations do. These enterprises are not only resilient because of their products but also because of the robustness of their manufacturing systems (Li & Pogodin, 2019). By recognizing the heightened level of completion in the global markets and in regional ones as well, most of these SMEs are looking to improve their capabilities by embracing smart manufacturing processes (Li & Pogodin, 2019). Based on this understanding, there is a possibility to integrate the principles of the “Made in China 2025” concept to enhance the operations of these firms. The improved adaptability for the SME sector is partly occasioned by the increased government attention directed towards the growth of the sector. Indeed, as stated by Holzmann and Kärnfelt (2020), Beijing has resolved to support SME growth as one of the tools for mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy.

In line with the “Made in China 2025” plan, policymakers have developed and ratified 600 policies designed to support SME growth in China (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020). They aim to create a supportive environment for these enterprises to thrive and they are partly designed to give preferential tax treatment to SMEs, enable them to get cheaper electricity costs, and lower their insurance expenses, among other benefits (Li & Pogodin, 2019). Most of these measures are intended to reduce the strain in liquidity, which affects the growth of most firms. Additionally, the government has introduced measures to enable SMEs to better integrate new technologies in their operations for better efficiency and synchrony with international business practices. These measures seek to improve their adaptability to the present business environment.

Enhanced Competitiveness

The “Made in China 2025” concept has led to the growth and development of Chinese SMEs because most of them are enjoying government support (Jian et al., 2019). Giant multinationals, such as Huawei and ZTE, are examples of firms enjoying government support, despite being privately run (Jian et al., 2019). The Chinese government is mobilizing state-backed corporations to collaborate with local SMEs to achieve the same level of success that Huawei and its peers have realized (Ling, 2017). This plan involves the deployment of different fiscal and monetary tools, such as subsidies and low-interest loans, to enable SMEs to gain access to new streams of financing and new market opportunities (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021). These opportunities are open to most local companies in China, but government support is covert to avoid implications that may arise from critics who view it as biased. It is unclear what the scale of financial support local SMEs are likely to enjoy from the implementation of this strategy but studies estimate that it could be in the hundreds of billions of dollars (Holzmann & Kärnfelt, 2020).

The involvement of government support in the running of Chinese SMEs under the “Made in China 2025” program has created a unique opportunity of increasing their competitiveness in the global market. Additionally, SMEs are likely to venture into the same fields as their larger competitors do because they can adopt new technologies easily if given state support (Jian et al., 2019). This is unlike giant enterprises that have to be subjected through rigorous systems of approval before changes can be effected. Furthermore, focusing on the digitization of SME products means that these firms would also become more competitive than their counterparts who stick to the conventional ways of manufacturing (Jian et al., 2019). Therefore, the integration of smart technologies into the operational practices of these firms would automatically lead to the development of smart factories that could compete effectively with others in the global market.

The role of the Chinese government in supporting local SMEs can be best analyzed through the pursuit of its central planning policy that has characterized its economic leadership vision since the 1990s (Economy, 2018). It involves coordinating policy planning activities across different levels of economic management, including government, academia, and business (Jian et al., 2019). This type of coordination occurs on two levels. The first one involves the implementation of publicly stated policies on economic planning and governance, while the second one involves opaque actions pursued by the state (Economy, 2018). Some analysts believe that such actions are meant to protect the country’s leadership from accusations of not abiding to World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments (Jian et al., 2019). Nonetheless, Chinese SMEs show promise of improving their competitiveness on the global stage if they receive state support.

Enhanced Innovation

Forced transfer agreements is also a strategy currently being used by the Chinese government to implement its “Made in China 2025” plan. It stems from a government policy requiring foreign companies to enter into partnership agreements with local companies as a precondition for doing business in China (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Under this arrangement, some foreign companies have been forced to disclose their trade secrets and technological skills to their Chinese counterparts who later integrate the same skills into their local processes (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Some foreign companies have complained about this practice, saying that it denies them access to the benefits of their intellectual property but most local companies have benefited from it, as it has led to their growth and development (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Some of the sectors that have directly benefited from the implementation of this policy include the battery-manufacturing, electric vehicle, and high-speed rail sectors (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Given the mounting criticism for the implementation of China’s local policies, the Chinese government has since relaxed some of them (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). An article authored by Prud’homme (2017) also discusses the same issue using the utility model patent regime that the Chinese government has adopted.

The author considers China to be among a larger group of Asian countries, including South Korea and Japan, which have pursued aggressive policies to aid local businesses benefit from their foreign counterparts through technological transfers (Prud’homme, 2017). Relative to this assertion, he says, these countries “pursue a dynamic catch-up strategy of transitioning from imitative to more sophisticated technological development by increasing both the strictness and appropriateness-strength of their utility model patent regimes in conjunction with increasing knowledge accumulation and, to some extent, technological capabilities” (Prud’homme, 2017, p. 1). In light of this statement, it is believed that China will likely benefit from tightening its utility patent model because it would foster creativity and innovation. The second theme that characterized the data analysis process related to the impact of the “Made in China 2025” concept on the integration of SMEs into the global manufacturing chain. Articles that were relevant to this subject area were assigned “code 2” to represent evidence that would be relevant to answering the second research question. Their findings are highlighted below.

Impact of “Made in China 2025” on the Integration of SMEs into the Global Manufacturing Chain

The “Made in China 2025” vision is partly pegged on foreign acquisitions and investments (Tong & Wan, 2017). This is because foreign partners would help SMEs to gain access to technologies that could be useful to the development of their local business processes. The current government policy of China, backed by the “Made in China 2025” focus, encourages state and private firms to invest in foreign companies (Tong & Wan, 2017). Particularly, most of them are being encouraged to invest in semiconductor firms because of their centrality to producing high-tech products (Tong & Wan, 2017). Some background statistics reveal that China is one of the biggest buyers of semi-conductors in the world, accounting for about 60% of global demand (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). However, it only contributes 13% of the global supply of the same product (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Given that the “Made in China 2025” plan seeks to promote a self-sufficiency level of 70% for local SMEs, the semiconductor sector has been of particular interest to the Chinese government (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). The support given by the Chinese government to local enterprises to invest in foreign firms partly informs the high levels of involvement of Chinese firms in the US economy. Today, the value of Chinese acquisitions in the US is estimated to be in excess of $45 billion (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Based on these numbers, the “Made in China 2025” concept appears to be making positive contributions towards the integration of SMEs in the global value chain.

The implementation of the “Made in China 2025” concept has been undermined by trade wars between countries that have made it difficult for Chinese SMEs to integrate into the global manufacturing chain (Alexandru-Mircea & Marilena-Oana, 2018). Particularly, the trade war between China and the US has given America justification to pursue aggressive economic policies aimed at isolating Chinese companies from the US and allied states (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). These actions have been supported by accusations and counter accusations about China’s adherence to international trade rules (Alexandru-Mircea & Marilena-Oana, 2018). The pursuit of the “Made in China 2025” objectives in the global marketplace has further complicated the situation because western powers believe that the government policy is aimed at advancing the interests of Chinese companies at the expense of foreign firms (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). To this end, some foreign governments have levied high taxes and tariffs on Chinese products, while others have prevented Chinese firms and their affiliates from making major acquisitions or mergers in the global market (Alexandru-Mircea & Marilena-Oana, 2018). This reaction to the growing influence of Chinese firms in the global economic system means that SMEs are having a more difficult time integrating into the same system than they should.

Overall, the “Made in China 2025” industrialization policy has been highlighted as an example of the overzealous nature of Chinese government policy in protecting its domestic interests at the expense of foreign ones (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). In this regard, the pace at which Chinese SMEs can integrate into the global economic system is suppressed by the negative perception that current players in the global economic system have towards China. However, Calza et al. (2019) suggest that quantum economic growth can only be realized when technology is deployed in scalable industries. They also propose that the progress can only be realized when countries subscribe to a global standard of operations because it is the best way to guarantee premium productivity (Calza et al., 2019). These findings have been affirmed by another researcher who analyzed the relationship between the internationalization of firms and their innovative capability among SMEs in Ireland. The investigation was conducted between 2004 and 2008 and it revealed that firms, which subscribe to global systems of operation, are likely to be more innovative than domestic ones. Similarly, they are better prepared to integrate new technologies than their local counterparts, thereby improving their labor productivity. The third theme that characterized the data analysis process related to the opportunities posed by the COVID-19 pandemic on the adoption of “Made in China 2025” concept in the Chinese SME sector. Articles that were relevant to this subject area were assigned “code 3” which represented research evidence that would be relevant to answering the third research question that focused on the same subject area. Their findings are highlighted below.

Opportunities Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Adoption of “Made in China 2025” Concept in the Chinese SME Sector

The COVID-19 pandemic helped to highlight the role that technology can play in supporting business operations. As mentioned in this study, it is difficult to comprehend the impact of the pandemic on businesses if modern technology was not as pervasive as it is today. According to Dai et al. (2021), 80% of SMEs in China closed business when the pandemic hit. Additional data indicates that between 19% and 25% of them closed permanently when the second wave was announced (Dai et al, 2021). Those that were operating when the two waves hit did so through technology or were in industries that were considered “essential services” and could not close down. In this regard, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the impact of technology adoption in the SME sector (Jiao et al., 2020). Given the potential of operating businesses via technological means in a pandemic, certain businesses, such as personal training and processes, like scheduling client appointments, have potential for growth because operations can be organized using technological tools, such as Zoom. The potential for technological adoption, which is at the core of the “Made in China 2025” vision, highlights leadership as the biggest opportunity for SMEs in a post-COVID world.

Leadership plays a critical role in ensuring that companies meet their objectives. The concept is associated with the need to motivate employees to achieve their full potential vis-a-vis their corporate objectives. The COVID-19 pandemic upset the global economic system, thereby fundamentally changing people’s perceptions of their jobs, workplaces, and even purpose in life (Ertel, 2021). It is important to recognize the distortion that this pandemic has had on the psychology of employees. Authors who have investigated these changes on Chinese households predict that the propensity to spend will decline as consumption subsides due to the pandemic (Zhao, 2020). At the same time, the demand for money is expected to surge and people are likely to be more cautious with their finances than would ordinarily be the case (Zhao, 2020). This realization calls for a change in leadership style because the present environment desires a new type of leadership that is not only centered on making sure financial objectives are met but also that employees are well taken care of and their interests matter in the overall running of businesses (Ertel, 2021).

China’s business culture is predominantly hierarchical in the sense that top leaders make most decisions while other employees implement them (Economy, 2018). As SMEs integrate in the global economic system, courtesy of the “Made in China 2025” plan, it will be important for business leaders in China to adopt new leadership styles that foster diversity and inclusivity in the workplace (Jiao et al., 2020). Doing so is important because different actors and players, from diverse backgrounds, characterize the global economic system (Economy, 2018). Given that firms will be more dependent on technology to transact business, these leaders could better nurture their skills in interpersonal communication in a multicultural setting (Jiao et al., 2020). The importance of adopting such an approach is embedded on the need to change the leadership styles adopted by most Chinese SMEs to become more inclusive and appealing to a diverse environment.

At the same time, the focus on leadership should be on why businesses do what they do and not how much they should earn (Ertel, 2021). This paradigm shift is informed by research evidence, which suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to increase people’s perceptive appeal to the role that businesses play in society (Ertel, 2021). In other words, it is not only enough for businesses to exist merely to satisfy the interests of their shareholders; they need to justify why their existence is important to others based on their contributions to society. Leadership practices need to demonstrate this fact (Economy, 2018). The fourth theme that characterized the data analysis process involved a comparison between China’s “Made in China 2025” plan and Germany’s “Industry 4.0” concept. Articles that were relevant to this subject area were assigned “code 4” to highlight research evidence that would be relevant to answering the last research question that focused on the same subject area. Their findings are highlighted below.

Comparison of “Made in China 2025” and Industry 4.0 Concepts

The “Made in China 2025” concept, albeit being a pioneer and ambitious futuristic state-sponsored plan, does not exist in isolation because other countries have drawn up similar plans to achieve the same goals. As highlighted in the first chapter of this study, the “Made in China 2025” concept shares close similarities with the Industry 4.0 concept (Matt et al., 2020). This similarity is the basis for the present comparison between both models. The Industry 4.0 concept was launched in 2013 (Matt et al., 2020) – two years before China launched the current plan. It is dependent on the use of the IoT to modernize its production processes, to link machines with one another, and connect them to a wider global network of operations through the internet.

The government of China justifies the “Made in China 2025” plan because it believes government support is necessary to increase the income of its citizens (Oberheitmann et al., 2020). They have given examples of how advanced nations, have benefitted from government support in their early years of development, including South Korea and the US (Ligang et al., 2019). Therefore, China believes that its “Made in China 2025” plan is similar to others pursued by other developed nations (Oberheitmann et al., 2020). Additionally, the government highlights inequalities in per capita income, between developed and developing economies, as a justification for the involvement of the government in corporate management (Ligang et al., 2019). Relative to this statement, a comparison of the per capita income between China and the US shows that the latter’s is $56,000 per year, while China’s is $8,000 (Ligang et al., 2019). These statistics mean that there is a significant difference in the earning potential of families in both countries. The Chinese government believes it needs to be involved in economic planning to bridge such gaps.

The use of technology as a tool to modernize the economy is further considered an inspiration to China from developed economies, such as Japan and Germany, which have adopted the same strategy to modernize their industries (Oberheitmann et al., 2020). Therefore, China believes that its “Made in China 2025” plan is similar to most others used by other nations around the world (Economy, 2018). However, critics differ and accuse China of pursuing unfair economic policies aimed at supporting its local businesses at the expense of foreign ones under the guise of implementing an economic model that differs from those pursued by the west (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2021). This accusation is part of the basis for comparison of the Made in China 2025 model and German’s Industry 4.0 concept. Similarities and differences that emerged from the present investigation are highlighted below.

Similarities

Researchers suggest that “Made in China 2025” and Industry 4.0 plans are similar because they both intend to advance manufacturing capabilities in their jurisdictions (Ling, 2017). Before the development of the “Made in China 2025” concept, the Chinese government originally developed its economic policies without considering their structures, priorities, or design (Ling, 2017). This omission was done relative to an organization or industry’s internal and external operating environment. The “Made in China 2025” concept seeks to solve these problems by establishing relationships between competitive abilities across industries. Research studies suggest that these relationships are linked with action plans that are similarly useful to promoting capability improvements among SMEs for better effectiveness and improved reliability of manufacturing processes (Jian et al., 2019; Ling, 2017). The Chinese model seeks to adopt unique techniques for achieving this goal. For example, Reverse Quality Function is proposed as the main feedback loop for analyzing operational functions within the plan. The priorities accorded under the “Made in China 2025” model are also ranked according to their area of importance to the economic development model of the country (Jian et al., 2019). However, unlike the German case, “Made in China 2025” has inherent weaknesses because China’s level of economic growth is not at par with Germany’s standards. Therefore, the “Made in China 2025” plan is designed to address inherent weaknesses relating to the Chinese economy, including transparency issues, innovation challenges and perceptions of poor quality (Matt et al., 2020). However, these problems do not affect the development of the Industry 4.0 plan. Therefore, the “Made in China 2025” plan focuses on several key competitive areas of capability improvement simultaneously.

Differences

The main difference between Industry 4.0 and the “Made in China 2025” concept is the type of technology being deployed. Unlike the “Made in China 2025” concept, which relies on the use of 5G technology and AI, Industry 4.0 relies on the Internet of Things (IoT) and web-based connectivity to integrate SMEs into the national economic network (Matt et al., 2020). This approach to development stems from the “Triple Bottom Line” approach to economic development, which focuses on promoting a country’s ecological, social, and economic benefits to all citizens (Matt et al., 2020). Unlike other economic models that preceded the Industry 4.0 framework, the current model focuses on aligning ecological and social benefits of development with economic ones.

Studies that have investigated the potential impact of Industry 4.0 and “Made in China 2025” also suggest that both concepts are likely to have a different impact on SMEs (Müller & Voigt, 2018; Matt et al., 2020). For example, there is cynicism regarding the impact that the Industry 4.0 concept would have on the German SME sector because it is perceived to be more beneficial to large enterprises compared to small ones (Matt et al., 2020). Comparatively, the “Made in China 2025” concept is perceived to have a positive impact on the potential social benefits that local SMEs could enjoy from its implementation (Müller & Voigt, 2018). The difference in outcomes is associated with strategies adopted by both China and Germany to achieve their economic objectives. For example, both countries have chosen to use state subsidies to support local businesses but the scope and scale varies. Germany’s state subsidies plan is smaller in scope compared to China’s (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Additionally, Germany’s state subsidies are dedicated to basic research but China’s subsidies are aimed at supporting fundamental business processes (Matt et al., 2020; McBride & Chatzky, 2019). At the same time, Germany does not pursue a local-centric government policy as China does. For example, unlike China, Germany does not intend to replace import quotas to benefit indigenous production (Matt et al., 2020), but the “Made in China 2025” plan has such provisions (McBride & Chatzky, 2019). Additionally, Germany’s economy is liberalized, unlike China’s. This makes it possible for Chinese firms to openly trade with German companies but firms from the latter encounter difficulties navigating China’s investment and market development laws.