Introduction

Notification Date and Time

On the morning of March 11, the Texas Department of Health (TDH) in Austin received a telephone call from a student at a university in south-central Texas. The student reported that he and his roommate, a fraternity brother, were suffering from nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Both had become ill during the night. The roommate had taken an over-the-counter medication with some relief of his symptoms. Neither the student nor his roommate had seen a physician or gone to the emergency room. The students believed their illness was due to food they had eaten at a local pizzeria the previous night. They asked if they should attend classes and take a mid-term biology exam that was scheduled that afternoon.

Outbreak’s Context

Any student who attends University X in south-central Texas, who ate at the university’s main cafeteria between March 5th and 10th, and presents with gastrointestinal signs and symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, headache, muscle ache, abdominal cramps, and high temperature would be considered a case. The university is in south-central Texas, in a small town with a population of 27,354. For the spring semester, during which the incident took place, the university had an enrollment of approximately 12,000 students; 2,386 students live on campus.

Date and Time Investigation Was Initiated by the Agency

TDH initiated investigations immediately, that is, on March 11, despite being skeptical of the student’s report. They began by making a few telephone calls to establish the facts and determine if other persons were similarly affected. The pizzeria where the student and his roommate had eaten was closed until 11:00 A.M. There was no answer at the University Student Health Center, so a message was left on its answering machine. A call to the emergency room at a local hospital (Hospital A) revealed that 23 university students had been seen for acute gastroenteritis in the last 24 hours. In contrast, only three patients had been seen at the emergency room for similar symptoms from March 5-9, none of whom were associated with the university. At 10:30 A.M., the physician from the University Student Health Center returned the call from TDH and reported that 20 students with vomiting and diarrhea had been seen the previous day. He believed only 1-2 students typically would have been seen for these symptoms in a week. The Health Center had not collected stool specimens from any of the ill students.

The Primary Objective(s) of the Investigation

The investigation’s primary aim was to determine whether the reported case implied a foodborne infection and the possible source of the pathogen. The move comes from the agency’s determination to remain proactive on matters of health promotion. Vomiting and diarrhea constitute part of significantly dangerous communicable health conditions worth immediate attention.

Background

Human norovirus, previously known as Norwalk virus, was first identified in stool specimens collected during an outbreak of gastroenteritis in Norwalk, OH, and was the first viral agent shown to cause gastroenteritis (Bozkurt et al., 2021). Illness due to this virus was initially described in 1929 as “winter vomiting disease” due to its seasonal predilection and the frequent preponderance of patients with vomiting as a primary symptom (Bhatta et al., 2020). While no pathogen could be identified in the Norwalk outbreak, oral administration of filtrates prepared from rectal swabs from affected individuals to healthy adult male prisoners at the Maryland House of Correction in Jessup, MD, resulted in symptoms (Bozkurt et al., 2021).The Caliciviridae family of small, nonenveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses is now comprised of five genera: Norovirus, Sapovirus, Lagovirus, Nebovirus, and Vesivirus (Bhatta et al., 2020). The human norovirus genome is composed of a linear, positive-sense RNA that is ∼7.6 kb in length. Clinical identification of this unique linear, positive-sense RNA thus confirms the infection’s presence.

Investigation Methods

Epidemiologic

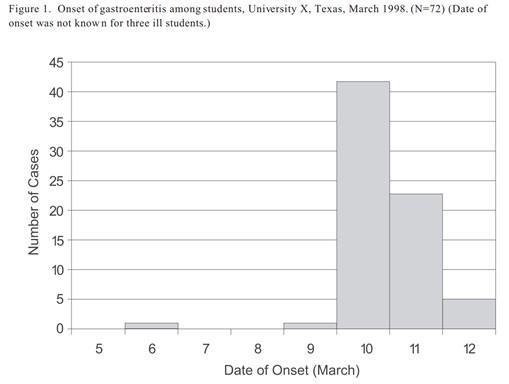

Thirty-one staff members were employed at the cafeteria of whom 24 (77%) were foodhandlers. Except for one employee who worked at the deli bar and declined to be interviewed, all dining service personnel were interviewed. By March 12, seventy-five persons with vomiting or diarrhea had been reported to TDH. All were students who lived on the university campus. No cases were identified among university faculty or staff or from the local community. Except for one case, the dates of illness onset were March 9-12. (Figure 1) The median age of patients was 19 years (range: 18-22 years), 69% were freshmen, and 62% were female.

Microbiological/Toxicological

TDH utilized its labs, the University Student Health Center, Hospital A, and CDC laboratories to investigate the case. On the afternoon of March 11, TDH staff visited the emergency room at Hospital A and reviewed the medical records of patients seen at the facility for vomiting and/or diarrhea since March 5. Based on these records, symptoms among the 23 students included vomiting (91%), diarrhea (85%), abdominal cramping (68%), headache (66%), muscle aches (49%), and bloody diarrhea (5%). Oral temperatures ranged from 98.8/F (37.1/C) to 102.4/F (39.1/C) (median: 100/F [37.8/C]). Complete blood counts, performed on 10 students, showed an increase in white blood cells (median count: 13.7 per cubic mm with 82% polymorphonuclear cells, 6% lymphocytes, and 7% bands). Stool specimens had been submitted for routine bacterial pathogens, but no results were available.

Environmental

All dining service personnel were interviewed, but for one staff who worked at the deli bar and declined to be interviewed. Sanitation procedures were established, including handwashing measures at the eateries. Eventual investigations showed that the employee who declined the initial investigations had a sick toddler. Investigators collected water and ice samples from the cafeteria on March 12, the results of which turned negative for fecal coliforms. Stool cultures and rectal swabs from the 23 food handlers were also negative for bacteria.

Results

Epidemiology Results’ Description

Case

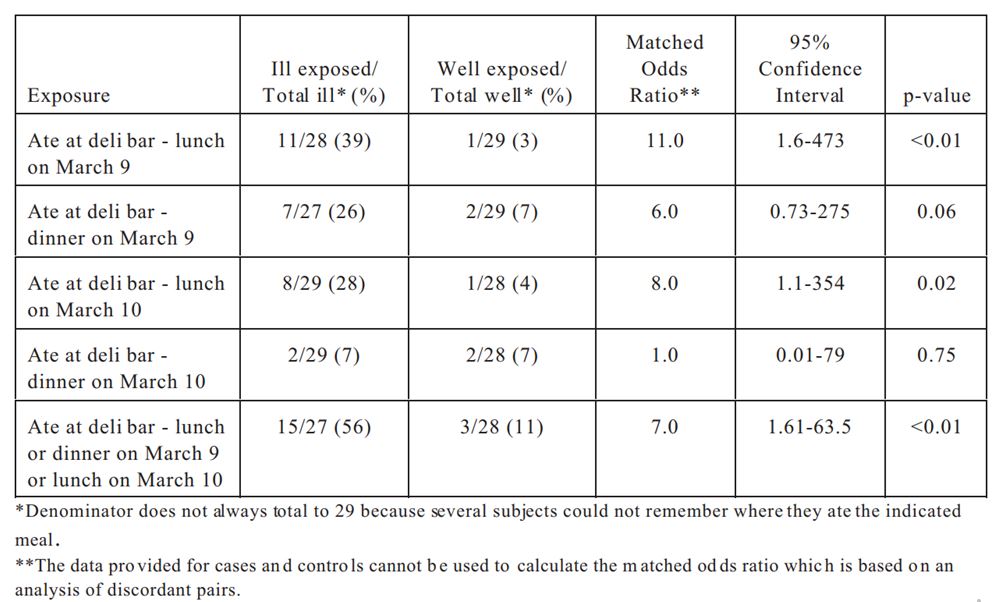

On the evening of March 12, about 36 hours after the initial call to the health department, TDH staff conducted a matched case-control study among students at the university. Ill students (reported from emergency rooms and the Student Health Center) who could be reached at their dormitory rooms were enrolled as cases. Dormitory roommates who had not become ill were asked to serve as matched control subjects. Investigators inquired about meals the students might have eaten during March 5-12 and where the foods were eaten. All information was collected over the telephone. Twenty-nine cases and controls were interviewed over the telephone. Investigators tabulated the most notable results in Table 1.

Table 1: Risk factors for illness, matched case-control study, main cafeteria, University X, Texas, March 2022

Demographic Data

By March 13, one hundred and twenty-five persons with vomiting or diarrhea had been reported to TDH. TDH invited staff from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to participate in the ongoing investigation. CDC staff suggested the submission of fresh stool specimens from ill students for viral studies, including reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). TDH and CDC staff decided to undertake an unmatched case-control study to further explore the source of the outbreak.

Clinical Data

The Deli bar was the focus because, during the past week, all but one student had eaten food from the establishment. This aspect makes the Deli bar in the main cafeteria the most likely source of the illness. The norovirus incubation period is likely 12-48 hours or 72 hours before the report of illness. Norovirus can be foodborne and spreads via direct contact. The main symptoms are vomiting and diarrhea; thus, symptoms align with those reported by the ill students.

Outcome of Illness

Ill students attending University X in south-central Texas, who ate at the university’s main cafeteria between March 5th and 10th, presented gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, such as vomiting, diarrhea, headache, muscle aches, abdominal cramps, and high temperature. The population provided the case for the investigations and the case-control procedure. Presenting these signs made students unable to attend classes or sit for continuous assessment tests. Some students got hospitalized, as indicated by the various consulted hospitals in the area. Fortunately, no death case was reported concerning the infection, while further observations are necessary to identify chronic effects related to the viral infection among the study population.

Microbiological/Toxicological

One hundred and twenty-five persons with vomiting or diarrhea had been reported to TDH by March 13. TDH invited staff from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to participate in the ongoing investigation. CDC staff suggested the submission of fresh stool specimens from ill students for viral studies, including reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Of the 18 fresh stool specimens sent on ill students to CDC, 9 (50%) had evidence of Norwalk-like virus (NLV) by RT-PCR. Of the four deli foods available from the implicated meals, only the ham sample from March 9 was positive by RT-PCR for the presence of NLV RNA. NLV was also detected by RT-PCR in a stool sample from the ill infant of the food handler who prepared the deli sandwiches on March 9. The sequence of the amplified product was identical to those products from the ill students and the deli ham.

Environmental

TDH environmental sanitarians inspected the main cafeteria and interviewed staff on March 12. There were thirty-one employees working at the cafeteria, of whom 24 (77%) were food handlers. In the cafeteria, the deli bar had its own preparation area and refrigerator. During mealtimes, sandwiches were made to order by a food handler. Each day, newly prepared deli meats, cheeses, and condiments were added to partially depleted deli bar items from the day before. Stool cultures were requested from all cafeteria staff. Before dinner on March 12, the City Health Department closed the deli bar.

Limitations of the Study

Investigations exhibited several limitations, including a small sample size and limited resources. Other difficulties included the inability to figure out which meal at the deli bar directly caused the infection. Large CI intervals and the small size of the investigation sample substantially affected the reliability of the acquired results. Equally, reliance on phone interviews implied facing delayed feedback due to inaccessibility among some respondents.

Conclusion / Discussion

The Main Hypothesis

Clinical findings, early cases’ descriptive epidemiology, and hypothesis-generating interview results led to the hypothesis that the source of the outbreak was a viral pathogen spread by a food or beverage served at the main cafeteria at the university between March 5 and 10. A positive correlation between eating and consuming products from the Deli bar between March 5 and 10 and the presentation of the symptoms among consumers justify the supposition.

The Likely Causative Agent and Mode of Transmission

Norwalk-like virus (NLV) is responsible for the infection at the school’s main cafeteria. The pathogen got there through an exposed food handler’s careless handling of ingredients. Of the 18 fresh stool specimens sent on ill students to CDC, 9 (50%) had evidence of Norwalk-like virus (NLV) by RT-PCR. NLV was detected by RT-PCR in a stool sample from the ill infant of the foodhandler who prepared the deli sandwiches on March 9.

Risk Factors

Eating in a place where food is handled by someone with norovirus infection or the food has been in contact with contaminated water or surfaces is a fundamental risk factor for norovirus infection. Other risk factors include attending preschool or a child care center and living in close quarters, such as in nursing homes. Similarly, residing in hotels, resorts, cruise ships, or other destinations with many people in close quarters and having contact with someone who has norovirus infection increases infection risk.

Measures to Control the Outbreak

The City Health Department closed the deli bar before dinner on March 12. The strategy followed preliminary investigations by TDH and the possible connection of the facility to the numerous infection cases. The point that the cafeteria served a substantially large number of students and staff, thus posing more infection risk, informed the decision. Further investigations, including clinical analysis, were undertaken to identify the infection, its specific cause, risk factors, prevention, and treatment.

Conclusions and Actions Taken

The evidence implicates the food handler as the source of the outbreak because of the genetic linkage to the norovirus. The infection caused is the sick infant belonging to the sick food handler, who reported not washing her hands even though she wore gloves. The condition is thus really easy to contaminate and highly communicable. The same genetic was identified, with March 9th being the matching date that most people got the illness; the Infant was ill since March 7th.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Controlling Disease and Mitigating Exposure

Recommendations to Improve Investigation and Management of Such Outbreaks in the Future

Investigations led to several recommendations, including throwing away all leftover deli bar foods and ingredients, cleaning and disinfecting all equipment and surfaces in the deli bar, and educating food handlers on proper food handling procedures. The cafeteria management was to work with the investigators to develop a sick food handlers policy to help the facility pay close attention to the disease in employees.

Measures to Prevent Similar Outbreaks in the Future

The Deli bar remained closed during the investigations to prevent further infections. The investigators worked with the cafeteria management to develop a sick food handlers policy that required the facility to pay close attention to the disease in employees. The policy was to start working immediately since norovirus can survive up to one month. An active communication channel where customers can inform the cafeteria and the college’s health clinic about such occurrences was developed to keep the facility in check.

Educational Message to the Public, Public Health Professionals, and Policy Makers

Functional cooperation among legal experts, major companies, food safety groups, and food safety consultants is necessary for food handlers, especially if one lacks knowledge regarding food safety. Food suppliers operating in colleges can benefit by partnering with the universities’ hospitality departments for proper policies and procedures. The health department can help develop safe food handling plans for secure operations.

References

Bhatta, M. R., Marsh, Z., Newman, K. L., Rebolledo, P. A., Huey, M., Hall, A. J., & Leon, J. S. (2020). Norovirus outbreaks on college and university campuses. Journal of American College Health, 68(7), 688-697. Web.

Bozkurt, H., Phan-Thien, K. Y., van Ogtrop, F., Bell, T., & McConchie, R. (2021). Outbreaks, occurrence, and control of norovirus and hepatitis a virus contamination in berries: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 61(1), 116-138. Web.