Introduction

In the contemporary setting, different sport competitions are considered as a method to demonstrate competitiveness civilly, whether they are on the local or the national level. Additionally, they are frequently linked to a special event giving the competition a certain symbolic nature. In that regard, the rewards bear not only the nature of financial incentives but sometimes a symbolic aspect as well. Tracing the tradition of rewarding the winners of such events, it can be seen that during various historical periods, different prizes were considered that had a relevant context in their corresponding time.

In that regard, this paper takes an approach toward analyzing the context of the Panathenaic amphorae, prizes given in the Panathenaic Games in ancient Athens, in terms of their historical background, the images on the amphorae, and the way they expressed the ideology of the polis, the Greek city-state.

The Festival of Games

The Panathenaic Games were one of the main parts of Panathenaia, a large festival dedicated to Gods in ancient Greece. Although there were many festivals dedicated to gods, it can be said that Panathenaia is one of the best known. The festival was incepted around the eighth or seventh century B.C., where the competitions were always a part of the festival. Major changes to the festival were implemented with the institution of the Great Panathenaia in about 566 B.C., where the games were reorganized, to include new competitions, particularly athletic games. Around the same time, the amphorae were introduced as prizes for the games, where “potters created a special type of vase to hold the valuable olive oil awarded to the victor in each contest” (Moore 37). The changes included the change from the annual nature of the festival to be performed every four years, while the duration assumingly remained the same, with the Panathenaia lasting several days. The festival was “held at Athens on the birthday of the goddess Athena, which was celebrated on the twenty-eighth day of the first month in the Athenian calendar, Hekatombeion (in July or August) (Dietrich von 52).

Panathenaia was one of two festivals solely dedicate to Athena, with the second festival being the cleansing festival (Plynteria and Kallynteria). Additionally, there was the festival of the threshing (Skira), in which Athena shared with grain goddess Demeter. However, despite the similarity in another festival through the dedication to Athena, the Panathenaia festival was distinguished through its inclusion of games. As all Athena’s festivals are projected in myth, the Panathenaia festival is no different in that matter. The festival symbolized in its rituals and actions a repetition of the great events of the past, and accordingly taking the dedication to Athena as a context, they all reflected the role of Athena in such events, which is to be stated was had a large part in them. In that regard, the festival of games “commemorates her role in the war between the gods and the primordial Giants” (Neils 28). The list of the events and competition, although was subject to changes during centuries, commonly included torch race, athletic contests, divided into gymnastic events and pentathlon events, heavy events such as boxing and wrestling, and finally team events. (Neils 97)

The Amphorae

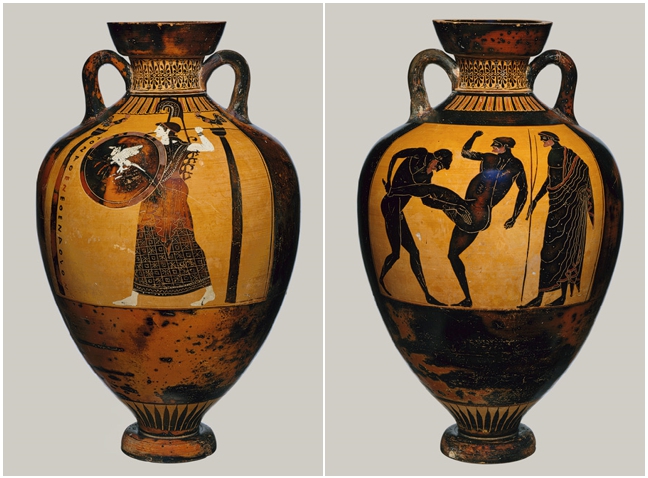

The Panathenaic amphorae, given as prizes in the Panathenaia festival to the winner of the games, can be described according to the canonical example held in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art 14.130.12., dated about 520 B.C. The amphora represents a vase with a very wide body, a short neck, and a narrow echinus foot. The standard liquid measure held by the vase is around 38 and 39 liters, decorated in the Attic black-figure technique. The vase has two sides representing two different drawings, where on one side there is always depicting Athena, while the other side depicts the sporting event for which this amphora was given as a prize (see figure 1).

It should be stated that the canonical Panathenaic prize looked the same from 530 B.C. until the end of the fifth century (Moore). Accordingly, the shape of the vase, although an important indication, given the name Panathenaic shape, it was argued that the prizes were only the vases which have the inscription “(one) of the prizes from Athens” (Neils 137) additionally, according to the constitution of Athenians, these vases were filled with olive oil, which was considered as part of the prize as well.

The Context

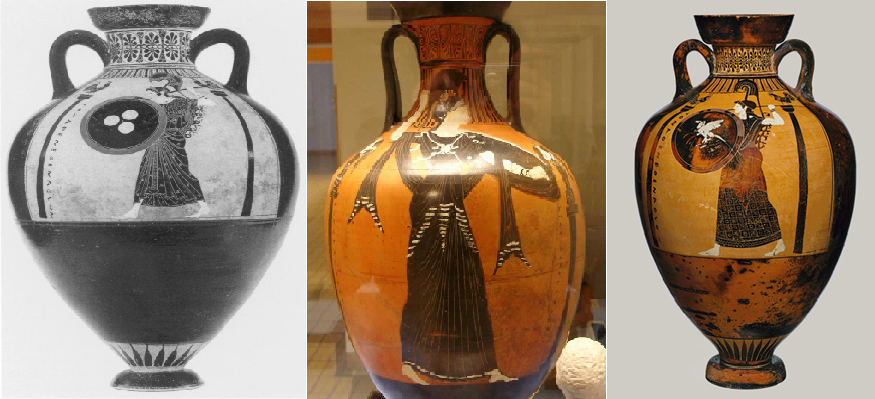

The main context of receiving the Panathenaic prize amphorae can be seen through the definition and the distinction of prizes, as “proofs of prowess, symbols of superiority, and tokens of triumph” (Neils 106). The distinction can be seen through the specific nature of the amphorae themselves, which leave no doubt on the way they were obtained. In that regard, it should be stated that Athenian potters also painted so-called pseudo-Panathenaic amphorae, which were distinguished by the absence of the inscription telling that the amphora is a prize from Athens, and smaller sizes (Neils 122). In that regard, it can be stated that the inscription itself served as an indication that the carrier of such prize is a person with certain qualities, and the other side of the amphora, showing the sporting competition, will indicate in what way.

The significance of the amphorae can be seen on two levels, which can be seen through the cultural impact as well as assumingly a motif for the polis in Athens. On the one hand, the development of the prizes for the sporting competition shows, that initially the rationale for giving the prizes was seen as a sponsorship gesture, where the prizes were valuable items, rather than symbolical. In that regard, prizes were given in gift-giving rituals in funeral games, in return for the prestige of sponsorship. Such stage in prize-giving was followed by symbolic prizes in the form of wreaths, starting in the late eighth century B.C. This was mainly because prize giving was institutionalized by the state, to shift the prestige of giving, which no wealthy aristocrat was willing to let another gain, to the state. Accordingly, the last stage is the subject of the paper, i.e. the Panathenaia games in the 6th century B.C., where the prizes combined the symbolism and the value. The value can be seen through the olive oil filled in the amphorae, which was initially gathered from sacred olive trees (Neils). The symbolism can be seen through linking the prize to worshipping Athena, the drawing of which can be seen as an essential element in prize amphorae (see Figure 2).

On the other hand, the context of the prizes had a particular rational motif for Athens Polis. As the participants of the competition were not only from Athens, the winners were taking their prizes to their homeland. At the same time, the winners might not have needed so much oil and amphorae, and thus, having the right to sell their prizes, the amphorae were spreading through various cities and settlements. In that regard, being filled with the local product, the oil, and inscriptions showing the origin of the prize (see figure 3), the fame of Athens was spreading as well, where the amphorae served as means for advertisements for the city, the festival, the local product, etc (Neils).

In that regard, it can be seen that the nature of the festival, in which the amphorae were given had many context for both receiving and giving the prize. The nature of the event had a symbolic context, which was transferred on the amphorae making them “sacred and civic, symbolic and valuable” (Neils 122)

Works Cited

“Attributed to the Kleophrades Painter: Panathenaic Prize Amphora (16.71)”. New York, 2000. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Web.

Dietrich von, Bothmer. “A Panathenaic Amphora.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 12 2 (1953): 52-56. Print.

Moore, Mary B. “”Nikias Made Me”: An Early Panathenaic Prize Amphora in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 34 (1999): 37-56. Print.

Neils, Jenifer. Worshipping Athena : Panathenaia and Parthenon. Wisconsin Studies in Classics. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996. Print.

Saint, Bibi. “The Goddess Athena on a Panathenaic Prize Amphora”. 2006. The British Museum. Web.