The supply chain incorporates processes aimed at meeting customer requirements and demands. The activities are associated with the flow of goods and transformation from the raw materials stage to point of end-use. Additionally, it entails the flow of information and funds (Terry and Hau 43). The stages involved include the supply network, the internal chain of supply, the distribution networks, and finally the end-consumers.

Management approaches and strategies used in supply chains are vital in the determination of manufacturers’ successes. Until recently, planning and execution were based on ad hoc methods. Recently developed methods have however been able to accommodate all stakeholders involved and hence ensure that the right amount of products are manufactured and distributed to desired locations. Additionally, it involves meeting service requirements and keeping staff happy.

It is the expectation of every corporation that procurement and supply processes are kept in line by ensuring that materials are availed on time to meet the demands and requirements of consumers. Poor market forecasts often result in unnecessary raw material purchases and hence excessive inventories. Inventory management decisions have the ability to make or break a firm (Terry and Hau 49). Push and pull systems are one of the management approaches employed in supply chain management.

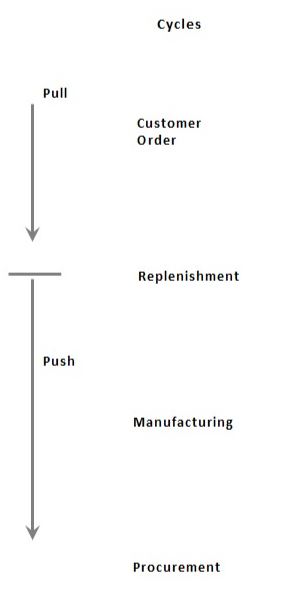

Push and pull are business terms widely used in the management of supply chains for a long time. They describe product/information movement amongst chain participants. Presumably, the consumers “pull” the goods/information to meet their demand while the supplies “push” the products to the consumers. Simultaneous operation of push and pull systems in supply and chain management is not a new concept (Cecere and Hofman 67). The point of intersection of the two marks the push-pull boundary also referred to as the decoupling point.

However, in purely push-based supply chain systems, products are pushed through the distribution channel from the point of manufacture to the retailer. Production targets are set based on the historical ordering patterns recorded from the clients (Hagel and Brown 51). Such systems take a longer time to respond to demand variations and hence commonly experienced bottlenecks and delays in addition to compromise on quality and product obsolescence. In purely pull supply systems, all processes including procurement, manufacture, and product distribution are driven by consumer demands (Terry and Hau 56). Process coordination is dependent on customer records and not forecasts. The case presented on the processing of “chicken sandwich salad” is a direct presentation of a pull system. The stringent schedule and perishability of products make it almost impossible for the producer to work by inventories. Instead, the manufacturer largely relies on consumer demand (Cecere and Hofman 67). Procurements for raw materials are done in relation to the intended output. Te outputs are dependent on the demand of that particular day. For instance, the demand is highest on Tuesday through to Thursday and begins to decline on Friday.

While part of the process is pulling, not the whole chain is based on the pull. To some extent, the procurement and the manufacturing cycles are purely pushed whereby products are pushed to the supply cycle continuously. The management has structured operations in such a way that staff is more relaxed and not overstressed with work. Scheduling of tasks is based on time scales and demands associated with the time. Production scheduling is based on demand capacity, balancing of shift durations, minimization of work during unsocial hours, customization of off days along with staff conditions, accommodation of time offs and vacations, and schedule flexibility (Cecere and Hofman 67). The system at this point is purely reflective of the pull management philosophy.

Cycle view of its supply chain operations

Supply chain models are meant to fulfill customer requirements and hence keep the firm in business. Failure to meet customer demand increases the likelihood of a firm’s failure. The main actors in supply chains often include suppliers, sub-contractors, manufacturers, transporters, warehouses, retailers, and customers. Its functions include product, development, marketing, procurement, manufacturing, operations, distribution, finance, and customer service. However, its primary focus is often to maximize the value generated through customer satisfaction. Decisions involved in the formulation of supply chains are illustrated in the table below:

Decision Phases

The cycle relates the link between the push and pull system employed in the supply chain. The chain begins with the procurement cycle where raw materials are obtained in preparation for manufacturing. While procurement is based on customer demand, manufacturing cycle is unconcerned about demands; it instead focuses on processing the raw materials presented to it. At this stage, the process is purely a push system where materials are processed and pushed to the next stage regardless of the constraints. From the manufacturing cycle, the next is the replenishment cycle which is an interface of push and pulls system. While pushing the material to the consumers, the push relies on the pull by the clients whereby order request are fulfilled and requested products dispatched.

Generalized illustration of the cycle

Push-Pull view of S.C.

Supply Models

There are two things that make supply processes great:

- Alignment: How well strategy and performance of supply operations fit with the company and the overall business strategy.

- Agility: The speed at which supply operations can respond to opportunities and requirements

Alignment means that strategic trade-offs are cascaded down to individual activities. Alignment introduces an end-to-end perspective and helps in avoiding local optimizations at the expense of the overall result. Can we draw a direct line between line between supply activities and those of the CEO and the board? CEOs don’t really care about the details of Go-to-Market or deployment. DCOR, CCOR, SCOR and PLCOR supports interaction at the level of discussion where they want to understand supply operations (Supply Chain Council 23): Top line (revenue), bottom line (margin), and long-term potential (adoption).

DCOR defines the design chain which include a number of processes namely; research design, integration and amendment, and aligning the same with operational strategy, product, work and flow of information. It generally facilitates management of a product life cycle. A number of metrics are used in its evaluation including reliability, of designed products, responsiveness to the needs of the clients, flexibility of manufacturing operations to changing needs, management of production assets, and innovativeness (Supply Chain Council 24).

CCOR on the other hand defines the consumer chain as the integrated process of planning, relate, sell, contract, and assists, spanning consumer demands and aligning them to operational strategies, consumers, products, work, and flow of information. Basically, it focuses on consumer lifecycle management. DCOR takes consideration of a number of factors including reliability of the corporations, consumer views, client responsiveness, flexibility to customer needs, costs associated with product sale, management of customers as assets to the corporation, and profitability as per the revenue generated from clients (Supply Chain Council 31). The table below summarizes the reference models and theire relation.

Generally, the supply chain operations in the discussed case presents two important categories with regard to SCOR Level 1 metrics. These include the customer oriented category and the internal oriented category. As much as the producer would want to satisfy consumer requirements, it must do so within sustainable limits. It is on this basis that internal oriented category is developed whereby; costs and assets available are put into consideration (Supply Chain Council 33). On the other hand, customer oriented category includes reliability, responsiveness and flexibility to demand fluctuations. This is best summarized by the table below:

SCOR Model:

Works cited

Cecere, Lora. and Hofman, Debra. The Handbook for Becoming Demand Driven. London: AMR Research, 2005.

Hagel, John. and Brown, John. From Push to Pull- Emerging Models for Mobilizing Resources. Working Paper, No. 3, 2005.

Supply Chain Council. Supply Chain Operations Reference Model. s.l. : The Supply Chain Council, Inc., 2008.

Terry, Harrison and Hau Lee. Neale The Practice of Supply Chain Management. Springerlink, 2003. Web.