Introduction

Since 1993 there has been a steady increase in the prison population, hitting a record highest of 87,000 inmates in 2012. While the rate of crime and other injustices on the fall, it is evident that the influx of the prison population results from longer sentences passed by the courts for criminal activities. The legislature has enacted strict legislative actions to curb crime and injustice to peaceful co-existence among the citizens and the government. Compared to other European nations, the UK alone and wales have the highest prison rate per square population, with the figures at 139 per 1000 population (Ministry of Justice, 2022; MacDonald, 2018; McLeod et al., 2020). However, these figures are more miniature when contrasted with countries like the USA.

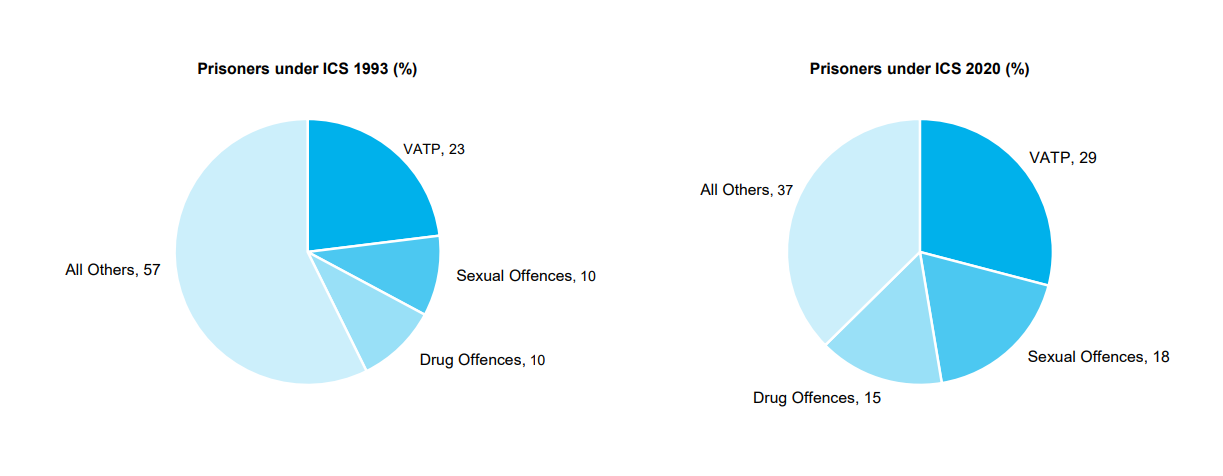

Since the record high figures in 2012, the population has significantly reduced regarding the number in 2012, 87,000 noted particularly in 2017. Uncertainties like the covid-19 pandemic also led to a decrease in the figures amid calls from the health department to decongest the prisons to lower the chances of attracting or spreading the virus (Hewson, Green, Shepherd, Hard & Shaw, 2020; Kinman, & Clements, 2021). Since the lockdown of 2020/2021, the prison population has reduced significantly by 6%, with approximately 5,500 inmates within the UK and Wales. Among the reasons that have led to increasing inmates are; increases in Immediate Custodial Sentences, increment of more serious criminal activities that necessitate longer sentences, and an increase in the length of jail terms for a specific crime. Sexual assaults and drug offences, to be precise, have their sentences increased significantly to above four years (Ministry of Justice, 2022). Moreover, life sentences mean that convicted offenders would serve the rest of their prison time. Since 2002, the number of whole life prisoners has risen by 40%; the figure recorded as of 2016 was 7,361 inmates serving life imprisonment.

Factors Leading to Rising Prison Population

The rising number of prisoners since 1993 has been influenced by several factors, among them stiffer judicial rulings and amendments that have necessitated longer jail terms for specific offences, recalls and the increased speed at which judgments were made by the courts (MacDonald, 2018). Discussed below are the reasons that have resulted in the influx of inmates in the UK and wales since 1993. There are fears that despite the reduction in crime rates in recent years, the number of inmates will rise by another 24% by March 2026 (Pakes, 2022; Allen, 2020). The government will be looking to expand prisons as penitentiaries among other correctional centres to match the numbers then.

Immediate Custodial Sentences (ICS)

An increase in ICS has significantly influenced the rise in the prison population since 1993 in immediate custody sentencing. Of the sentenced from ICS, prisoners were expected to serve four years or more, accounting for the increase in the prison population (Jones, 2019). ICS reduced the amount of time spent for courts hearings making judges and magistrates give their rulings or verdicts on the first hearing. There has been a significant fall in the population of the remanded population due to the rise in immediate custodial sentences. Compared to those in remand in 1999, the numbers have dropped by 1000 people since being sentenced and serving their time. ICS alone has led to an increase in the prison population by 20% since 1993. Those convicted from verdicts of ICS account for 46% of the increment of the prison population (Ministry of Justice, 2022). This has led to an increase in inmates from increased speed of sentencing.

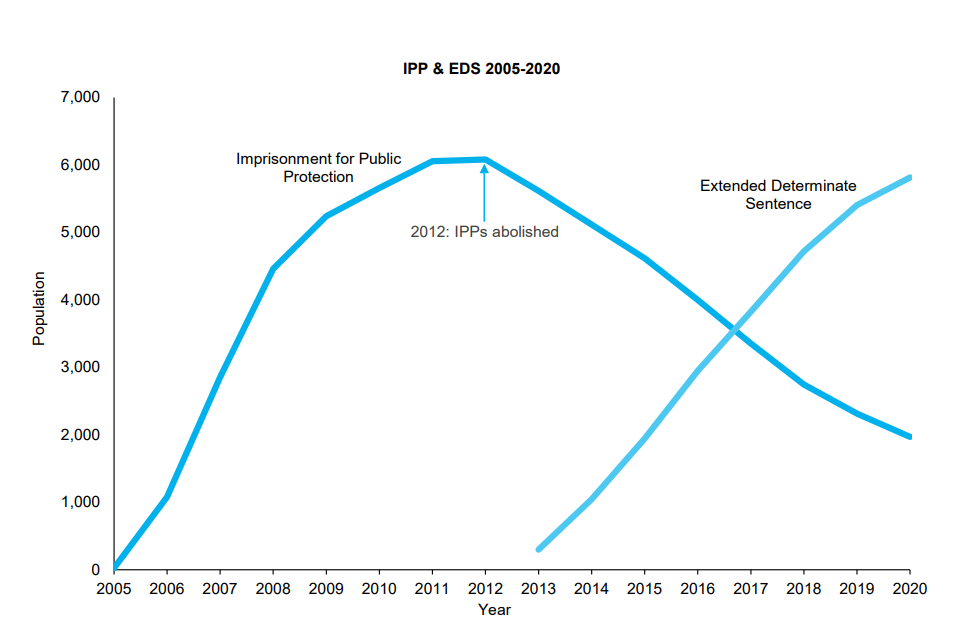

Extended Determinate Sentences (EDS)

With the rise of Violence Against the Person (VATP) sexual and drug offenses, the Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) was replaced with Extended Determinate Sentences (EDS) in 2012 (Lee & Walker, 2022). The EDS meant that prisoners would spend longer terms in licensing periods besides their initial convicted period. There was a significant increase in the population of prison inmates between 2015 and 2016 after the enactment of the EDS. The number of inmates serving under the EDS rose by 50%, equivalent to 2949 from 1476 in the previous year (2015). Prisoners serving under the EDS act are not to be released until at least they do two-thirds of their terms. Should the correctional centers fail to perceive change, the convicts will have to serve their full jail terms, often four years.

Average Custodial Sentence Length (ACSL)

The period between 1993 to 2010 saw a steady average custodial sentence duration for immediate determinate offenses at approximately two months and two days. The number of have, however, risen drastically and doubled to around five months and two days in 2019. The average has increased due to the rise in serious offences and hence more convicted offenders (Jones, 2019). Due to the nature of the violations, longer jail terms have been imposed on such offenders leading to prolonged stay at correctional institutions and increasing the prison population henceforth. Moreover, the introduction of the EDS in 2012 also contributed to the increase in ACSL since inmates spent a more prolonged period than were sentenced to jail time to conduct probation and monitoring before being released back to society (Lee & Walker, 2022). On average, inmates released in 2019 had spent five months and 19 days more than those released for similar offences in 1999.

Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP)

The Criminal Justice Act (2003) saw the introduction of Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP), a type of sentence where serious criminal offenders were held for indefinite periods while monitoring change (Vanstone & Priestley, 2022; King & Crisp, 2021). Despite the previous acts, the courts did not deem them to warrant life sentences. The first convict under the act was handed in 2005. The numbers then rose steadily throughout the period up until 2012, when the EDS was introduced in lieu of the IPP. Cases whose verdicts were IPPs accounted for 77% of the increase in the prison population for the period between 2005 to 2012. Despite the act being dropped in 2012, convicts already serving under the IPP had to complete their terms (Barrister, 2022). There was a notable drop in the population of inmates serving IPP after the enactment of the EDS in 2012.

Life Sentences

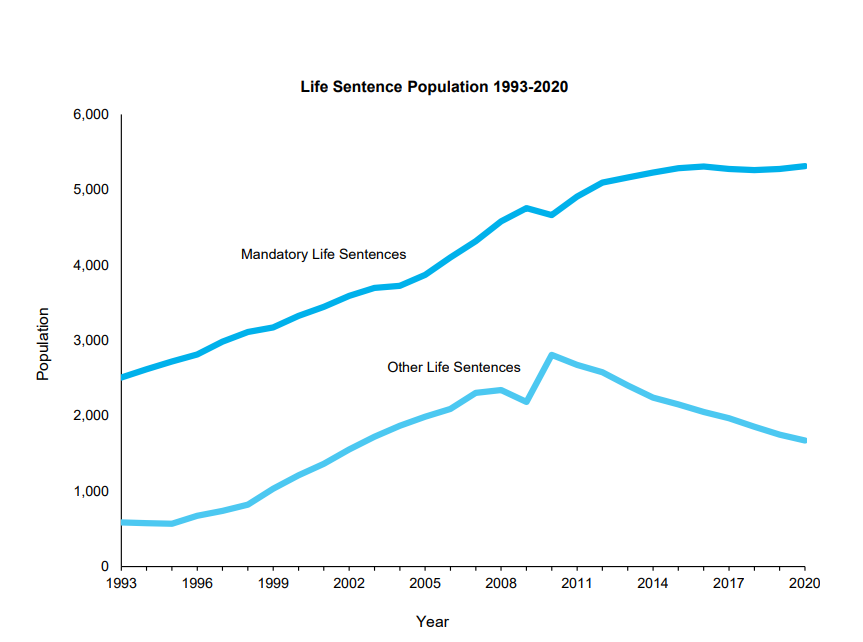

Life sentences mean that convicts will spend the rest of their time in prisons. Prisoners can be locked for a lifetime behind bars or placed on parole; for the latter, prisoners may be released by the parole board where significant change is observed from the prisoner, but a lifetime license is issued that warrants their arrest if breached (GOV.UK, 2022; Seeds, 2021).). The court may hand a maximum life sentence to those found guilty of rape and armed robbery. The decision by the court to pass a lifetime sentence depends on the extent of the offence as presented by prosecutors and the potential risk that the public might be exposed to at the expense of releasing the convict (Council, 2022; Coffey, 2021). Life sentences come in different ways as detailed in this paper.

Mandatory life sentences are passed by judges where suspects are found guilty of committing the grievous crime of murder; then, they must spend the rest of their time in jail (Coffey, 2021; Heard & Jacobson, 2021). The judge has the mandate to sentence these suspects to life imprisonment. For whole life order, those found guilty will serve the rest of their time in prisons. Discretionary (other) life sentences on the other hand are passed for these cases, that despite warranting life imprisonment, the judges or magistrates may consider the severity of the case and decide to alter their rulings.

The number of prisoners serving mandatory lifetime sentences has increased by 50% compared to 1993. In 1993, prisoners serving lifetimes tallied to 2,400, figures doubled 2020 to approximately 5,000. On the contrary, the population of those serving other life sentences has reduced, despite a spike in 2011 (about 2500) due to introducing alternative sentencing options, EDS, and IPPs precisely. The numbers have increased the population in prisons around the UK and wales. Furthermore, second-time offenders of Violence and sexually related offences are automatically sentenced to life imprisonment. The increases in diversity in terms of lifetime sentencing have led to more lifetime judgements, meaning more time spent in jails, increasing the prison population.

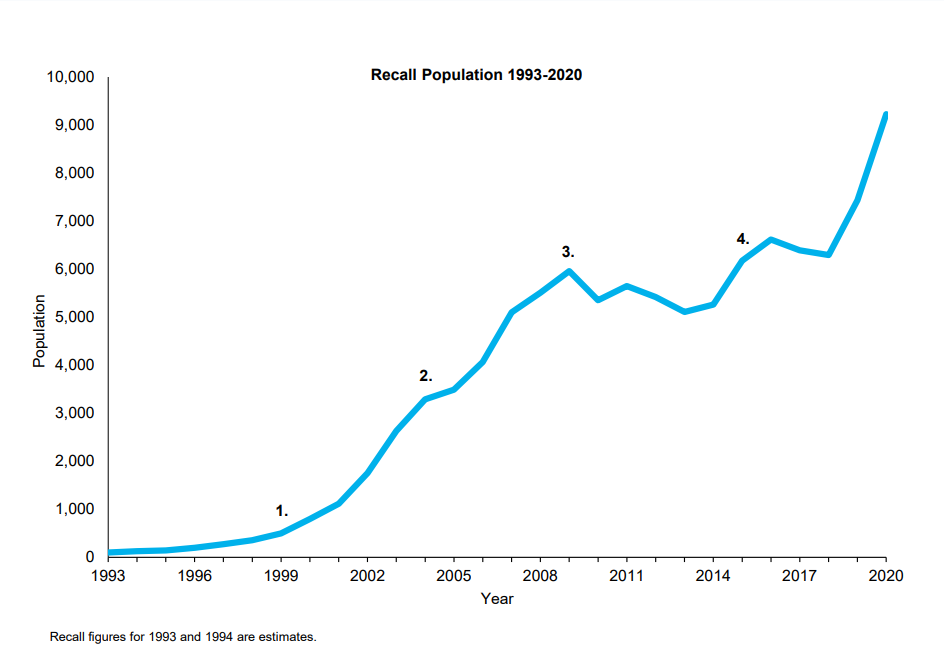

Recall

Even after release from jail, acts like the EDS require continued monitoring of ex-convicts to assure that their being in society does not put the life or wellbeing of the public in any form of danger. Failure to oblige to license terms, prisoners serving under such licenses are returned to prisons immediately upon violation of the license terms (Marcinkowski, 2018). The recalled population has increased tremendously from a meagre 100 people in 1993 to 9000 people in 2020. Since the periods for sentences are more extended, recalls in case of their existence would also take longer. Recall periods for sentences shorter than 12 months and those over 12 months take 14 days and 28 days, respectively. The average time spent for recalls at correctional centres is 28 days for most recall acts. The population of recalled prisoners has been rising from 1993 to 2020 despite decreasing the overall prison population, raising alarms on the impact of correctional institutions (Marcinkowski, 2018; Jones, 2021). Various Acts regulate the duration and conditions for recalls; the Crime & Disorder Act of 1998, the Criminal Justice & Immigration Act of 2008 and the Offender Rehabilitation Act of 2014. All factoring in the length and weight of the initial sentence and the license terms breached. Recalled prisoners eventually i ncreased the number of inmates.

Demographic Changes

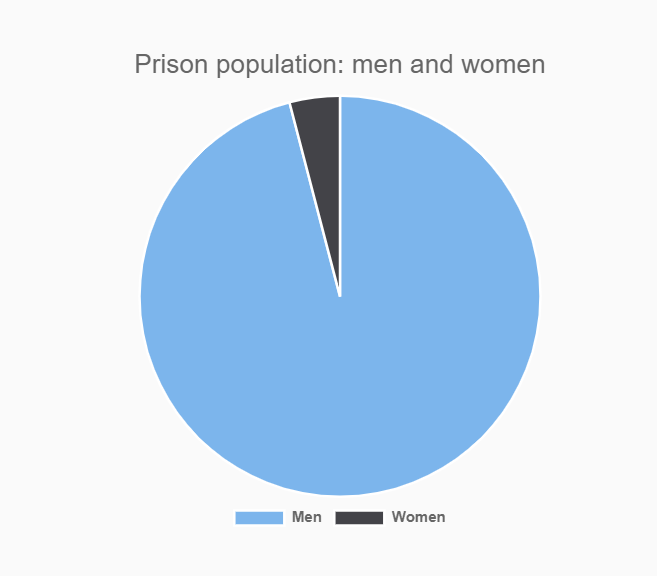

The change in demography UK and wales over time has led to an increase in the prison population. People from the new-age brackets are involved in crime and criminal activities, leading to sentences. Between 1993 and 2012, there was an increase in prisoners falling in ages between 30-49. From 2012 however, there has been an increase of offenders aged between 20-29, and those between 50-69, that was not observed earlier. This has resulted in the influx of prisons, with sentences taking longer. An increase in male prisoners also impacted the influx of the prison population in the UK and Wales. Males reserve a higher percentage of crime involvement, 3.9%, than women at 3.4%. Moreover, males are more likely to commit domestic violence and abuse than women on the receiving (Statista, 2022). The population of males involved in crime and criminal activities is steadily rising, impacting the population of males in prisons; this is also evident in the number of male penitentiaries compared to female correctional centers.

Despite females recording low figures overall on the prison population, they recorded the highest increase in several convicted prisoners between 1993 and 2012, with a positive average growth rate of +5.2% per year compared to that of males that were at +3.5% annual growth rate up until 2012 (Wild et al., 2021; Stürup-Toft, O’Moore & Plugge, 2018). Since 1993, the Foreign National Offender (FNO) population has been on the rise with an approximated average of +6.2% annual growth rate, compared to that of UK and Wales nationals at +3.5% annually (League, 2022; Collinson, 2021). The increase was also spiked between December 2019 to mid-2021, when FNOs could not be released from prisons amid covid-19 pandemic turmoil.

Finding

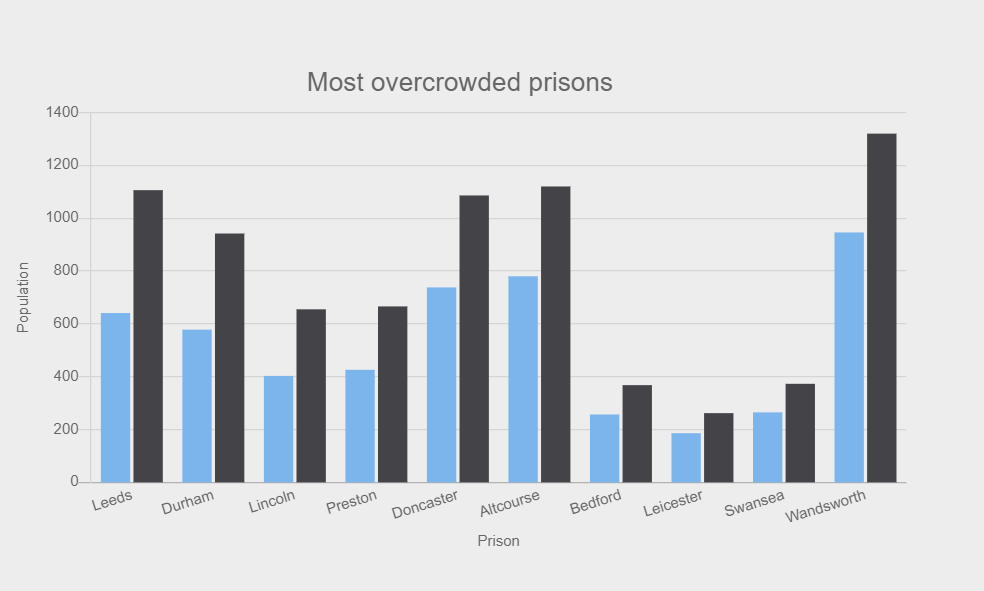

The rising prison population has impacted negatively on the sole mandate for prisons: rehabilitation and character rectification. The problems arising from crowded prisons are; health, security, staffing, classification, sanitization, restoration, and sociability (Piper, Forrester & Shaw 2019; Franke et al., 2019; Moran, Jones, Jordaan & Porter, 2021). Increased prison population also forces the government to allocate more to prison facilitation (McLeod et al., 2020). The number of recalls has been growing since 2012. This is despite a decrease in the number of prisoners since that period (MacDonald, M. 2018). The government should also invest in staffing to improve the quality of rehabilitation activities and the number of rehabilitators (Bolger, 2019). Despite being held behind bars, inmates have the right to meet their families through visitations (conjugal, compassionate), which are equal measures to effective rehabilitation (Moran, Jones, Jordaan & Porter, 2021). Overcrowded prisons are not only a threat to humanity by violation of prisoners’ human rights but to lives of prison wardens and attendants. The rise in ICS is the leading cause of the influx in the prison population in the UK and wales.

Conclusion

The Certified Normal Accommodation (CNA) recommends that the total number of inmates in the UK be less than or equal to 76,332 people. The numbers are currently above that required population evidencing the crowded prison population in the UK and Wales. With the prison population projected to rise by 2026, the government should focus on improving prison facilities and increasing staff. Covid-19 has also impacted the people of the prisons and has raised alarms on the need for prisons decongestion.

Reference List

Allen, J. (2020). Embedding user-centred design in policymaking at the UK Ministry of Justice.

Barrister, D., 2022. Release from Custodial Sentences — Defence-Barrister.co.uk. [online] Defence-Barrister.co.uk. Web.

Bolger, M. (2019). End of Life in Prison. Winston Churchill Memorial Trust: London, UK.

Coffey, G. (2021). An exploration of ECtHR jurisprudence governing the administration of release processes for life and long-term sentence prisoners: Perspectives from the United Kingdom. New Journal of European Criminal Law, 12(4), 594-621.

Coffey, G. (2021). Perspectives from the United Kingdom. New Journal of European Criminal Law, 12(4), 594-621.

Collinson, J. (2021). Deporting EU national offenders from the UK after Brexit: Moving from a system that recognizes individuals to one that sees only offenders. New Journal of European Criminal Law, 12(4), 575-593.

Cornwell, D. Prisons, Politics and Practices in England and Wales 1945-2020.

Council, S., 2022. Sentencing – Sentencing Council. [online] Sentencingcouncil.org.uk. Web.

Franke, I., Vogel, T., Eher, R., & Dudeck, M. (2019). Prison mental healthcare: recent developments and future challenges. Current opinion in psychiatry, 32(4), 342-347.

GOV.UK, 2022. Types of prison sentences. [online] GOV.UK. Web.

Heard, C., & Jacobson, J. (2021). Sentencing burglary, drug importation and murder: evidence from ten countries.

Hewson, T., Green, R., Shepherd, A., Hard, J. and Shaw, J., 2020. The effects of COVID-19 on self-harm in UK prisons. BJPsych Bulletin, [online] 45(3), pp.131-133. Web.

Jones, R. (2019). Sentencing and immediate custody in Wales: a fact file.

King, N., & Crisp, B. (2021). Conceptualizing ‘success’ among Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentenced offenders with personality-related difficulties. Probation Journal, 68(1), 85-106.

Kinman, G., & Clements, A. J. (2021). New psychoactive substances, safety and mental health in prison officers. Occupational Medicine, 71(8), 346-350.

League, H., 2022. The Howard League | Prison watch. [online] The Howard League. Web.

Lee, F. and Walker, C., 2022. The sentencing of precursor terrorism crimes in the United Kingdom. [online] Elgar Online: The online content platform for Edward Elgar Publishing. Web.

MacDonald, M. (2018). Overcrowding and its impact on prison conditions and health. International journal of prisoner health.

Marcinkowski, W. (2018). The structure of English judiciary from the perspective of continental legal system. Internetowy Przegląd Prawniczy TBSP UJ, (2 (42)).

McLeod, K. E., Butler, A., Young, J. T., Southalan, L., Borschmann, R., Sturup-Toft, S.,… & Kinner, S. A. (2020). Global prison health care governance and health equity: a critical lack of evidence. American journal of public health, 110(3), 303-308.

Ministry of Justice, 2022. Story of the Prison Population 1993 – 2020 England & Wales. [online] Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. Web.

Moran, D., Jones, P., Jordaan, J. and Porter, A., 2021. Does Nature Contact in Prison Improve Well-Being? Mapping Land Cover to Identify the Effect of Greenspace on Self-Harm and Violence in Prisons in England and Wales. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, [online] pp.1-17. Web.

Pakes, F., 2022. Prison numbers set to rise 24% in England and Wales — it will make society less safe, not more. [online] The Conversation. Web.

Piper, M., Forrester, A., & Shaw, J. (2019). Prison healthcare services: the need for political courage. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(4), 579-581.

Seeds, C. (2021). Life sentences and perpetual confinement. Annual Review of Criminology, 4, 287-309.

Statista, 2022. UK: man vs female prison population 2019 | Statista. [online] Statista. Web.

Stürup-Toft, S., O’Moore, E. J., & Plugge, E. H. (2018). Looking behind bars: emerging health issues for people in prison. British Medical Bulletin, 125(1), 15-23.

Vanstone, M., & Priestley, P. (2022). Reducing the use of imprisonment. Lessons from Probation Day Centres in England and Wales: 1970–2000. Probation Journal, 02645505211070085.

Wild, G., Alder, R., Weich, S., McKinnon, I., & Keown, P. (2021). The Penrose hypothesis in the second half of the 20th century: investigating the relationship between psychiatric bed numbers and the prison population in England between 1960 and 2018–2019. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1-7.