Abstract

This study examines what facets of green logistics delivery practices have been studied to highlight the sustainable logistics practices reviewed, their efficacy, and the challenges that have been encountered. The paper was segmented into five parts to achieve its goals. For instance, the paper begins with an introduction that gives an overview of how sustainable practices influence contemporary supply chain management, specifically logistics (Klumpp, and Zijm, 2019, p. 213). The second segment provides the literature review where a critical review of the past papers was performed to determine the study’s status on green logistics delivery methods. The third section of the report presented the research methodology used for gathering the information.

Conversely, the research results are presented in section four, followed by the conclusion based on the findings. According to the reports, environmentally sustainable distribution systems have fewer movements, less processing, shorter transit times, more direct delivery paths, and improved truck usage. Modal transition, hybrid fuel innovation, path planning, appropriate network architecture, reverse logistics, and sustainable transportation procurement have all been listed as viable options. However, the costs of using electric cars, purchasing them, and technical issues have all been described as significant roadblocks.

Introduction

Transportation, construction, and electricity production are also examples of environmental emissions. It is generally accepted that logistics and shipping processes have a substantial adverse effect on the natural world due to these practices (Banihashemi, Fei, and Chen, 2019, p. 19). Furthermore, transport is one of the leading causes of environmental issues (García‐Dastugue, and Eroglu, 2019, p. 47). It is projected to rise much higher than the gross domestic product’s overall development in the developed world. Transportation leads to ecological problems primarily through air emissions and noise (Russo and Comi, 2020, p. 125; Jermsittiparsert, Siriattakul and Wattanapongphasuk, 2019, p. 23).

Organizations, transportation service suppliers, and policymakers have taken numerous measures to reduce the environmental effects of transportation and logistics-related practices due to the increased emphasis on transportation operations’ ecological emissions (Smith, Park and Liu, 2019, p. 4). As a result of several initiatives, cars have been more environmentally sustainable than before, but environmental measures have not kept up with increasing transportation volumes (Karaman, Kilic, and Uyar, 2020, p. 231). This suggests that simply considering steps to render cars more environmentally sustainable is inadequate and that a broadening of options for minimizing environmental impact is needed.

Concerns regarding environmental degradation triggered by numerous practices have risen in recent years, with transportation and logistics activities playing a significant role. To combat this detrimental impact, a variety of approaches have been used (Zowada, 2020 p. 34; Rantala et al., 2018, p. 6). The idea of going towards green logistics is a way of decreasing an institution’s environmental effects. Green logistics is described as “efforts to quantify and reduce the environmental effect of logistics operations.”

Consequently, it’s essential to recognize the sustainable logistics delivery activities that scholars have taken into account. Also, the efficacy of these practices and the problems encountered during execution should be determined (Centobelli, Cerchione and Esposito, 2017, p. 65). Only then will further studies be done to include answers to specific issues and consider potential research avenues. This research centered on the study query, “On what dimensions has research on sustainable logistics delivery practices been done,” with the goals of identifying the green logistics distribution practices that have been studied, determining their feasibility, and determining the problems and challenges associated with the activities.

Literature Review

This section will assist in establishing the connection between works in line with the research topic. This demonstrates how logistics is critical in maintaining a robust supply chain as an essential part of supply chain management. It schedules, executes, and monitors the movement and handling of products and services to ensure that consumer needs are met. As such, it is worthwhile to examine sustainability practices in the supply chain, especially in logistics.

Conception and Scope of Logistics

As per Khan et al. (2020, p. 111), logistics is the monitoring of the movement of products from the production and demand points to satisfy conditions, like those of consumers or companies. Physical products like food, equipment, livestock, machinery, and fluids, and abstract products like time, knowledge, particles, and energy, are among the resources handled in logistics. Information processing, material storage, manufacturing, shipping, procurement, transport, warehousing, and, in some instances, protection is all part of the logistics of specific goods (García‐Dastugue and Eroglu, 2019, p. 63) Dedicated modeling tools can simulate, interpret, visualize, and maximize the complexities of logistics. Exports and imports logistics are guided by a need to consume as little capital as possible (Lim, and Jones, 2017, p. 69; Wijethilake, 2017, p. 39). However, as can be seen, the idea of logistics is based on product movement, it also emphasizes stock management practices such as product storage, shipping, delivery, manufacturing, and refining (Kayikci, 2018, p. 88). Despite the fact that company logistics encompasses a wide range of practices, conventional facilities management analysis on logistics focuses mostly on the areas of logistics service, storage, and inventory preparation.

Logistics and supply chain management

The Council of Logistics Management defines logistics as the aspect of supply chain management that schedules, manages, and monitors the reliable, productive forward and reverse movement and storage of products resources, and related details between origin and the consumption points to satisfy consumers’ needs (Tavasszy, 2020, p. 65; Teixeira et al., 2018, p. 62). Even though the words “logistics” and “supply chain management” are frequently interchanged, they apply to two different facets of the operation (Rodríguez et al., 2016, p. 6). As explained, logistics corresponds to what occurs within a single organization, one of the several supply chain operations. Supply chain management, besides, refers to a broader range of activities carried out by a more significant network of companies to supply products to consumers and handle returns and pollution.

Order processing, warehouse control, materials preparation, storage of goods, network design, inbound or outbound shipping, fleet administration, procurement, and to various degrees manufacturing and acquisition, data management, production scheduling, storage, and consumer care are all examples of logistics management. As per Fettke et al. (2010, p. 67), the key goal of logistics is to plan these operations in such a manner that they satisfy consumer needs while being as cost effective as possible.

Defining sustainable logistics

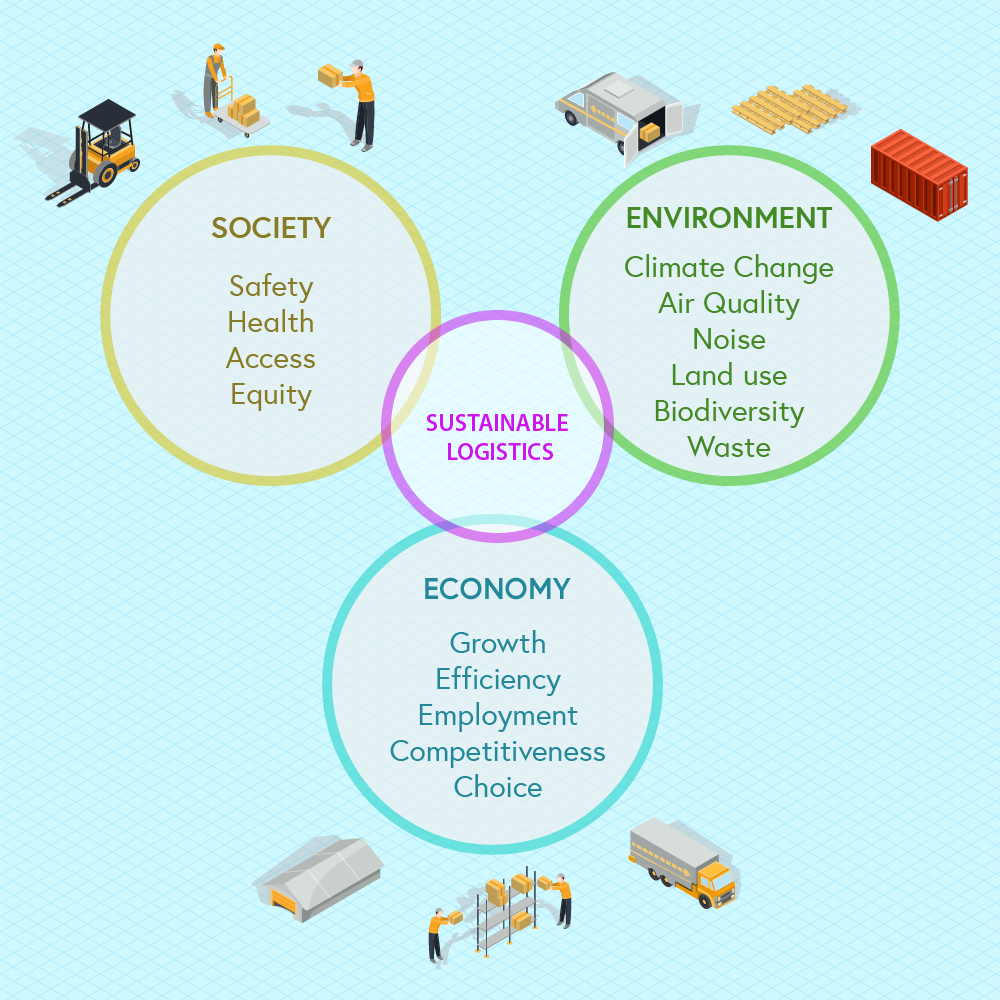

With the rising value of green supply chains, the emphasis has increasingly shifted to greening logistics operations, intending to meet consumer needs not only by lowering costs involved but rather by lowering expenses related to climate change, air quality, vibration, noise, and incidents. Greener logistics, according to the Brundtland study from 1987, can be described as the production and distribution of merchandise in an environmentally friendly manner, taking into account environmental, monetary, and social aspects (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020, p. 54). Organizations must make choices on their logistics activities that include the financial, technical, and social components of the Triple Bottom Line to reach a more balanced equilibrium between environmental, economic, and social goals (see figure 1).

The economic and Social Dimensions

The economic viability of logistics is essential for two reasons: to maximize the value contributed to the enterprise (for example, sales, properties, and consumer support levels) and to minimize associated logistics expenses by using existing services more efficiently. Companies must spend in both quantity and standard of service and promote the production of new and reliable logistics systems to accomplish this (Zhao et al., 2020, p. 42). Similarly, there are some dimensions of the social aspect of logistics. First, logistics companies must adopt strategies and management processes to safeguard workers’ interests in compliance with current legislation. Second, companies must adapt to the market understanding of sustainable practices by importing eco-materials, using green energy sources, and minimizing logistics operations’ environmental effects. Third, steps like switching to more environmentally friendly forms of transportation or reducing road congestion necessitate consumer acceptance (Klumpp et al., 2016).

The Environmental Dimension

Finally, the environmentally friendly handling of reverse and forward commodity and knowledge flows between the point of production and consumption is referred to as logistics’ environmental component. According to Feichtinger and Gronalt (2021, p. 12), green logistics is defined as business practices that consider ecological problems and integrate them into logistics administration to improve vendors’ and buyers’ environmental efficiency (Goswami et al., 2020, p. 211; Rad and Nahavandi, 2018, p. 41). According to Hallikas, Lintukangas and Kähkönen, (2020, p. 63), the assessment of the environmental effects of transportation and collection methods, the elimination of energy consumption of logistics operations, the minimization of waste outputs, and the regulation of their disposal are all examples of green logistics operations.

Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate social responsibility is a term that refers to a company’s social responsibilities (CSR). Apart from charitable work, Li et al. (2021, p. 65), Zaman and Shamsuddin (2017, p. 28), Gupta et al. (2020, p. 2) identify two other ‘auditoriums’ for CSR: organizational development and innovative market models. The effect of CSR policies on sourcing and supply chain management and how supply chain administrators integrate or execute CSR initiatives are topics of concern in the OM literature (Stekelorum et al., 2021, p. 36; Goswami et al. 2020, p. 89; Macchion et al., 2018, p. 104). Alagarsamy (2021, p. 12) and Bortolini et al. (2019, p. 81) look at how social ventures create profit, while Alexandrova et al. (2021, p. 45) and Indrianingsih and Agustina (2020, p. 20) look at them from a supply-chain viewpoint.

In essence, there is skepticism regarding whether or not a modern organization will or should fulfil its social responsibilities (Chowdhury and Quaddus, 2021, p. 9). This skepticism can clarify why studies on “socially conscious activities” focus on social entrepreneurs, small farmers, foundations, and other non-profit organizations. A few articles in the supply chain and operations publication concentrate on large-company projects such as ITC’s e-choupal, a digital portal that provides peasants with the corporation’s buying price a day ahead of time.

Why an ethical supply chain is important

Organizations must have access to evidence when it comes to sustainable working processes, sharing and partnering with collaborators and clients. Providing reliable and complete insight into data from all facets of the supply chain allows businesses to satisfy customer demands. It also allows them to demonstrate how they do so (Demirel and Eskin, 2021, p. 93). Consumers expect businesses to have ethical standards, show honesty, and take a stance on existing and broadly relevant topics such as openness, equal work, and conservation, as per Accenture. Approximately half of the consumers believe that one of a brand’s most appealing characteristics is honesty (Schiehll and Kolahgar, 2021, p. 59). Customers speak up to protest and avoid doing business with a company when they struggle in these ways. Today, 65 per cent of shoppers claim to have a meaningful impact through their daily transactions. According to Nwoba, Boso and Robson (2021, 92), DiVito and Bohnsack (2017, 23), clients are more educated and demanding than ever before, with studies indicating that nine out of ten millennials would switch products if they think it is more ethical. There may be a $633 billion market for companies who prioritize honorable work conditions.

Supply Chain Sustainability to Suppliers

The dyadic viewpoint of supply chains provokes the attention of the current research on the standing point of vendors in SCSI. The research on supply chain management shows that vendors and focal firms have different perspectives on supply chain characteristics, including knowledge exchange, partnership quality, and efficiency enhancement (Fan, Lo and Zhou, 2021, p. 2). This discovery is also helpful in the analysis of Sustainable development. The dyadic outlook of the supply chain means that manufacturers and focal firms have varying perspectives on SCSI. Whereas focal corporations anticipate successful performance enhancement, as Fernández and Ceacero-Moreno (2021, p. 98) say, suppliers see SCSI as a means of compliance with focal corporations in the supply chain. This difference would affect SCSI vendors’ financial and operating efficiency.

Rimin et al., (2021, p. 6) define focal organizations as those that control or administer the supply chain, have direct consumer interaction and plan the product or service provided. As environmental and social issues arise in the supply chains, they are more likely to face legislative demands, regulations, or opposition from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Zowada, 2021, p. 44; Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020, p. 67; Pérez-Mesa et al., 2021, p. 88). Furthermore, benefits and strategic advantages gained by the establishment of a sustainable supply chain, like credibility benefit and premium costs, cause them. Vendors, besides, have little incentive to incorporate environmental or social issues into their business activities (Rjoub et al., 2021, p. 13). NGOs and government legislation less closely monitor suppliers in the supply chain than focal businesses. In some instances, they are not in charge of environmental and social matters. Focal companies seldom state how they would compensate vendors for their contributions to supply chain efficiency.

As a result, since supply chain sustainable development implementation expenses are borne mainly through vendors, suppliers will believe that they would not be paid for participating in SCSI to offset the costs. As a result, vendors are also hesitant to participate in supply chain sustainable development (Alexandrova et al., 2021, p. 30; Sonia and Khafid, 2020, 261). Whenever the focal business is under strain, it usually transfers the burden to its vendors (Rimin et al., 2021, p. 108; Hardiningsih et al., 2020, p. 77). To secure the sourcing partnership, focal organizations compel vendors to enter supply chain sustainability efforts. As a result, the most common reason for manufacturers to join a sustainable supply chain is to satisfy the demands of focal firms. As a result, supply chain sustainable development is typically implemented by focal firms, with retailers acting as passive participants.

Methodology

A qualitative approach is the most appropriate approach for this form of study, as described in the literature review. As a result, this study was carried out as a material survey. A total of sixty research articles were considered since a lack of research directly focused on sustainable logistics delivery activities. The keywords ‘sustainable logistics delivery methods’ were used to scan the internet archive for related research papers. A critical review of the documents was conducted to determine the status of the study on green logistics delivery methods. Following that, the feasibility of green logistics delivery activities was investigated, and the problems and challenges associated with the practices.

Results

As per the study’s conclusions, modal change and the usage of intermodal transportation is a technique that has been explored in the literature. Since transportation activities account for a significant portion of every logistics system’s pollution (Feichtinger and Gronalt, 2021, p. 34; Baah, Jin and Tang, 2020, p. 11), much of the previous logistics research has concentrated on its long-term sustainability. In a European sense, shifting transportation types from quicker, more environmentally harmful modes like road and air to sluggish, less carbon-emitting modes like train or marine transport is a widely proposed step to reduce the ecological effects of transportation (Sousa et al., 2021; Reche et al., 2020, p. 45).

Intermodal road-rail options, which combine road and rail transportation, have been proposed as a potential route to minimize CO2 pollution from logistics sector transportation operations (Adedoyin, Bekun and Alola, 2021; Larson, 2021, p. 71). On 19 European routes, a new report looked into how CO2 pollution improved due to a transition from unimodal truck shipping to intermodal road-rail transport (Stojanović, Ivetić, and Veličković, 2021, p. 67). According to the report, the modal change reduced CO2 pollution by 20 to 50 percent for these 19 pathways.

According to environmental process management practices, modal transition, which refers to converting less environmentally sustainable transportation models to more environmentally friendly models, may have a significant effect on the global climate. Tesco, for example, uses rail instead of vehicles to transport goods between the Midlands and central Scotland, saving about seven million road miles and 6,000 tonnes of CO2 each year (Larson, 2021, p. 73; Mosteanu et al., 2020, p. 4; Jia et al., 2020, p. 18). The European Commission claimed in their White paper that logistics would help achieve sustainable transportation goals by assisting with mode change (Justavino-Castillo, 20020, p. 14; Richnák, and Gubová, 2021, p. 90).

Conclusion and Discussion

When looking at the numerous solutions that have been explored in the study, it is evident that several different green logistics strategies have been discussed. The techniques have also been debated at various stages. As seen by many studies and since pollutants are directly linked to the form of transportation used, modal shift and intermodal transport can be inferred as techniques that lead significantly to sustainable logistics. The configuration of transportation handling and the logical selection of shipping routes to efficiently increase vehicles’ real load rate and round-trip loading rate is a technique that has been considered in many articles. Several similar sustainable logistics solutions have been widely explored, including using environmentally safe fabrics, improving resource use, developing foldable packs to increase vehicle capacity utilization rate, enhancing packaging designs (eco-design). Also, approaches to minimize the amount of packaging and protective product by lightweight design.

On the other side, little study has been done on using tactics and technology such as speed control, left-hand turn decreases, GPS units, and automated engine shut down equipment. However, some businesses have limited the number of left turns in practice, and organizations utilize GPS to monitor vehicle travel. While not explicitly linked, including preparation, environmental knowledge exchange, and collaborative analysis is an important technique that has been established. Although a bit of study has been conducted on this method, it may be claimed that it is an essential strategy because human resources are a significant part of an organization’s operation. Training and education in green logistics activities would affect everybody from upper management, making business choices to middle management and lower-level management to make more environmentally sustainable practices. The fact that reverse logistics techniques have been studied less in emerging nations and more in industrialized countries is a notable result.

The results indicate that eco-sustainable logistics systems are distinguished by fewer moves, fewer handling, short trips, more direct delivery paths, and more significant usage of vehicles. Efficient solutions were established for modal shifting, dual fuel innovation, road optimization, good network architecture, reverse logistics, and sustainable transportation procurement. Moreover, via this research, many hurdles were found. The barriers to the use of such cars, investment in procurement, and organizational challenges were found in general. Alternative energy use is limited by energy supply, car finance, repair, and market feasibility. Consequently, it should be proposed as a guideline for more study that efficient yet lightly explored techniques be investigated to render them more achievable. It may also be advised to research successful techniques that can make them more economically competitive since most large organizations already use these strategies.

References List

Adedoyin, F., F., Bekun, F., V., and Alola, A., A., 2021. ‘Roadmap for climate alliance economies to vision 2030: retrospect and lessons’, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 8(3), pp.1-12, Web.

Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., Ahenkorah, E., Afum, E., Dacosta, E., and Tian, Z., (2020), ‘Green warehousing, logistics optimization, social values and ethics and economic performance: the role of supply chain sustainability’, The International Journal of Logistics Management, 31(3), pp. 549-574, Web.

Alagarsamy, S., Mehrolia, S. and Mathew, S., 2021. ‘How Green Consumption Value Affects Green Consumer Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Consumer Attitudes Towards Sustainable Food Logistics Practices’, Vision, 25(1), pp.65-76.

Alexandrova, L.Y., Kireeva, O.F., Krasilnikova, E.V., Munshi, A.Y. and Timofeev, S.V., 2021. ‘Approaches to Solving the Existing Problems in Green Logistics’, In Frontier Information Technology and Systems Research in Cooperative Economics 3(1), pp. 857-868.

Arsić, M., Jovanović, Z., Tomić, R., Tomović, N., Arsić, S. and Bodolo, I., 2020. ‘Impact of logistics capacity on economic sustainability of SMEs’, Sustainability, 12(5), pp. 19-11.

Baah, C., Jin, Z. and Tang, L., 2020. Organizational and regulatory stakeholder pressures friends or foes to green logistics practices and financial performance: investigating corporate reputation as a missing link. Journal of cleaner production, 247(61), pp. 119-125.

Banihashemi, T., A., Fei, J., and Chen, P., S., (2019). ‘Exploring the relationship between reverse logistics and sustainability performance: A literature review’, Modern Supply Chain Research and Applications, 1(1), pp. 2-27, Web.

Bortolini, M., Galizia, F.G., Gamberi, M., Mora, C. and Pilati, F., 2019. ‘Enhancing stock efficiency and environmental sustainability goals in direct distribution logistic networks’, International Journal of Advanced Operations Management, 11(1-2), pp.8-25.

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., and Esposito, E., 2017. ‘Developing the WH2 framework for environmental sustainability in logistics service providers: A taxonomy of green initiatives’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 165(13), pp. 1063-1077.

Chowdhury, M., M., H., and Quaddus, M., A., 2021. ‘Supply chain sustainability practices and governance for mitigating sustainability risk and improving market performance: A dynamic capability perspective’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 278(32), pp.123- 130.

‘Demirel E., Eskin İ., (2021) ‘Investigation of the Effects of Environment on Financial Reporting. In: Çalıyurt K. T. (eds) Ethics and Sustainability in Accounting and Finance, Volume II. Accounting, Finance, Sustainability, Governance & Fraud: Theory and Application’, Springer, Singapore, 6(3), pp. 19-38, Web.

DiVito, L. and Bohnsack, R., 2017. ‘Entrepreneurial orientation and its effect on sustainability decision tradeoffs: The case of sustainable fashion firms’, Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), pp.569-587.

Fan, D., Lo, C., K., and Zhou, Y., 2021. ‘Sustainability risk in supply bases: The role of complexity and coupling’, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 145, p. 102-175.

Feichtinger, S., and Gronalt, M., 2021. ‘The Environmental Impact of Transport Activities for Online and In-Store Shopping: A Systematic Literature Review to Identify Relevant Factors for Quantitative Assessments’, Sustainability, 214(13), pp. 29-34.

Fernandez, P., and Ceacero-Moreno, M., 2021. Urban Sustainability and Natural Hazards Management; Designs Using Simulations. Sustainability, 13(2), pp. 639-649.

García‐Dastugue, S., and Eroglu, C., 2019. ‘Operating performance effects of service quality and environmental sustainability capabilities in logistics’, Journal of Supply Chain Management, 55(3), pp. 68-87.

Goswami, M., De, A., Habibi, M., K., K., and Daultani, Y., 2020. ‘Examining freight performance of third-party logistics providers within the automotive industry in India: An environmental sustainability perspective’, International Journal of Production Research, 58(24), pp. 7565-7592.

Gupta, H., Kusi-Sarpong, S., and Rezaei, J., 2020. ‘Barriers and overcoming strategies to supply chain sustainability innovation’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 161(5), pp. 104-119.

Hallikas, J., Lintukangas, K., and Kähkönen, A., K., 2020. ‘The effects of sustainability practices on the performance of risk management and purchasing’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 263(12), pp. 121-129.

Hardiningsih, P., Januarti, I., Yuyetta, E.N.A., ‘Srimindarti, C. and Udin, U., 2020. The effect of sustainability information disclosure on financial and market performance: Empirical evidence from Indonesia and Malaysia’, International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 10(2), pp. 12-18.

Indrianingsih, I. and Agustina, L., 2020. ‘The Effect of Company Size, Financial Performance, and Corporate Governance on the Disclosure of Sustainability Report’, Accounting Analysis Journal, 9(2), pp. 116-122.

Jermsittiparsert, K., Siriattakul, P. and Wattanapongphasuk, S., 2019. ‘Determining the environmental performance of Indonesian SMEs influence by green supply chain practices with moderating role of green HR practices’, International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(3), pp. 59-70.

Jia, F., Peng, S., Green, J., Koh, L., and Chen, X., 2020. ‘Soybean supply chain management and sustainability: A systematic literature review’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 255(9), pp. 120-254.

Justavino-Castillo, M.E., Gil-Saura, I. and Fuentes-Blasco, M., 2020. ‘Effects of sustainability and logistic value in the relationship between ocean shipping companies’, Estudios Gerenciales, 36(157), pp. 377-390.

Karaman, A.S., Kilic, M. and Uyar, A., 2020. ‘Green logistics performance and sustainability reporting practices of the logistics sector: The moderating effect of corporate governance’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 258(56), pp.171-188.

Kayikci, Y., 2018. ‘Sustainability impact of digitization in logistics’, Procedia manufacturing, 21(8), pp. 782-789.

Khan, S.A.R. and Zhang, Y., (2021). ‘Development of Green Logistics and Circular Economy Theory. In 2020 3rd International Seminar on Education Research and Social Science, 5(4), pp. 121-127.

Khan, S., A., R., Zhang, Y., and Nathaniel, S., 2020. ‘Green supply chain performance and environmental sustainability: a panel study’, LogForum, 16(1), pp. 56-71.

Khan, S., A., R., Zhang, Y., Kumar, A., Zavadskas, E., and Streimikiene, D., 2020. ‘Measuring the impact of renewable energy, public health expenditure, logistics, and environmental performance on sustainable economic growth’, Sustainable development, 28(4), pp. 833-843.

Klumpp, M. and Zijm, H., 2019. ‘Logistics innovation and social sustainability: How to prevent an artificial divide in Human–Computer Interaction’, Journal of Business Logistics, 40(3), pp. 265-278.

Larson, P., D., 2021. ‘Relationships between Logistics Performance and Aspects of Sustainability: A Cross-Country Analysis’, Sustainability, 13(2), p.623.

Li, X., Sohail, S., Majeed, M.T. and Ahmad, W., 2021. ‘Green logistics, economic growth, and environmental quality: evidence from one belt and road initiative economies’, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1(2), pp.1-11.

Lim, M., K., and Jones, C., 2017. ‘Resource efficiency and sustainability in logistics and supply chain management’, International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 20(1), pp.20-21.

Macchion, L., Da Giau, A., Caniato, F., Caridi, M., Danese, P., Rinaldi, R. and Vinelli, A., 2018. ‘Strategic approaches to sustainability in fashion supply chain management’, Production Planning & Control, 29(1), pp.9-28.

Melkonyan, A., Gruchmann, T., Lohmar, F., Kamath, V. and Spinler, S., 2020. ‘Sustainability assessment of last-mile logistics and distribution strategies: The case of local food networks’, International Journal of Production Economics, 228(26), pp.107-116.

Mosteanu, N.R., Faccia, A., Ansari, A., Shamout, M.D. and Capitanio, F., 2020. ‘Sustainability Integration in Supply Chain Management through Systematic Literature Review’, Calitatea, 21(176), pp. 117-123.

Navarro-Galera, A., Rodríguez-Bolívar, M.P., Alcaide-Muñoz, L. and López-Subires, M.D., 2016. ‘Measuring the financial sustainability and its influential factors in local governments’, Applied Economics, 48(41), pp. 3961-3975.

Nwoba, A.C., Boso, N. and Robson, M.J., 2021. ‘Corporate sustainability strategies in institutional adversity: Antecedent, outcome, and contingency effects’, Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), pp.787-807.

Pérez-Mesa, J.C., Piedra-Muñoz, L., Galdeano-Gómez, E. and Giagnocavo, C., 2021. ‘Management Strategies and Collaborative Relationships for Sustainability in the Agrifood Supply Chain’, Sustainability, 13(2), pp.731-749.

Rad, R.S. and Nahavandi, N., 2018. ‘A novel multi-objective optimization model for integrated problem of green closed loop supply chain network design and quantity discount’, Journal of cleaner production, 196(73), pp.1549-1565.

Rantala, T., Ukko, J., Saunila, M. and Havukainen, J., 2018. ‘The effect of sustainability in the adoption of technological, service, and business model innovations’, Journal of cleaner production, 172(4), pp. 46-55.

Reche, A., Y., U., Junior, O., C., Estorilio, C.C.A. and Rudek, M., 2020. ‘Integrated product development process and green supply chain management: Contributions, limitations and applications’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 249(67), pp. 119-429.

Richnák, Patrik; Gubová, Klaudia., (2021). ‘Green and Reverse Logistics in Conditions of Sustainable Development in Enterprises in Slovakia’, Sustainability 13(2), pp. 578-581, Web.

Rimin, F., Bujang, I., Wong Su Chu, A. and Said, J., 2021. ‘The effect of a separate risk management committee (RMC) towards firms’ performances on consumer goods sector in Malaysia’, Business Process Management Journal, 6(1), pp. 17-24.

Rjoub, H., Odugbesan, J.A., Adebayo, T.S. and Wong, W.K., 2021. ‘Sustainability of the moderating role of financial development in the determinants of environmental degradation: evidence from Turkey’, Sustainability, 13(4), pp.1840-1844.

Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P., Navarro Galera, A., Alcaide Munoz, L. and López Subires, M.D., 2016. ‘Analyzing forces to the financial contribution of local governments to sustainable development’, Sustainability, 8(9), p. 911-925.

Russo, F. and Comi, A., 2020. ‘Investigating the effects of city logistics measures on the economy of the city’, Sustainability, 12(4), p. 1400-1439.

Schiehll, E. and Kolahgar, S., 2021. ‘Financial materiality in the informativeness of sustainability reporting’, Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), pp. 840-855.5

Smith, H.J., Park, S. and Liu, L., 2019. ‘Hardening budget constraints: A cross-national study of fiscal sustainability and subnational debt’, International Journal of Public Administration, 42(12), pp. 1055-1067.

Sonia, D. and Khafid, M., 2020. ‘The Effect of Liquidity, Leverage, and Audit Committee on Sustainability Report Disclosure with Profitability as a Mediating Variable’, Accounting Analysis Journal, 9(2), pp. 95-102.

Sousa, P.R.D., Barbosa, M.W., Oliveira, L.K.D., Resende, P.T.V.D., Rodrigues, R.R., Moura, M.T. and Matoso, D., 2021. ‘Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned: Sustainability in Brazilian Omnichannel Retail’, Sustainability, 13(2), p. 659-666.

Stekelorum, R., Laguir, I., Gupta, S. and Kumar, S., 2021. ‘Green supply chain management practices and third-party logistics providers’ performances: A fuzzy-set approach’, International Journal of Production Economics, 6(2) pp.108-113.

Stojanović, Đ., Ivetić, J. and Veličković, M., 2021. ‘Assessment of International Trade-Related Transport CO2 Emissions—A Logistics Responsibility Perspective’, Sustainability, 13(3), pp.11-38.

Tavasszy, L.A., 2020. ‘Predicting the effects of logistics innovations on freight systems: Directions for research’, Transport Policy, 86(5), pp. A1-A6.

Teixeira, C.R.B., Assumpção, A.L., Correa, A.L., Savi, A.F. and Prates, G.A., 2018. ‘The contribution of green logistics and sustainable purchasing for green supply chain management’, Independent Journal of Management & Production, 9(3), pp.1002-1026.

Wijethilake, C., 2017. ‘Proactive sustainability strategy and corporate sustainability performance: The mediating effect of sustainability control systems’, Journal of environmental management, 196, pp. 569-582.

Zaman, K. and Shamsuddin, S., 2017. ‘Green logistics and national scale economic indicators: Evidence from a panel of selected European countries’, Journal of cleaner production, 143, pp. 51-63.

Zhao, Z., Zhang, M., Xu, G., Zhang, D. and Huang, G.Q., 2020. ‘Logistics sustainability practices: an IoT-enabled smart indoor parking system for industrial hazardous chemical vehicles’, International Journal of Production Research, 58(24), pp. 7490-7506.

Zowada, K., 2020. ‘Green Logistics: ‘The Way to Environmental Sustainability of Logistics. Empirical Evidence from Polish SMEs’, European Journal of Sustainable Development, 9(4), pp. 231-231.

Zowada, K., 2021. Going green in logistics: ‘The case of small and medium-sized enterprises in Poland’, Journal of Economics & Management, 43(4), pp. 56-73.