Famine is a global problem affected developing countries. The main causes of famine are low income and low developed economies. It is known that among the developed countries, increases in per-capita food production since the 1950s have generally moved upward in tandem with increases in total food production. Among the developing countries, per-capita food production has generally lagged behind.

Moreover, even in countries of the South where the Green Revolution has produced spectacular production gains, the distribution of its rewards has often been quite uneven (Fluehr-Lobban and Lobban 6). Recent decades the problem of famine has been examined more as a result of overpopulation than a crisis of entitlement.

Such authors as P. R Ehrlich and Mike Davis pay a special attention to the problem of overpopulation and its impact on famine. Researchers claim that population growth has a great influence on food shortage. Famine affects countries with the high average population growth rate.

They prove the fact that famine affects many countries with high average population growth rate. Countries on African continent belong to less developed countries which resulted in economic and social disasters influenced native population. The statistical date gives the facts that in Africa most people are seriously affected by famine and different diseases.

Researchers examine the general impact of overpopulation on the planet statistics. According to statistical results, every day 86,400 persons die because of famine. “On average, 62 million people die each year, of whom probably 36 million (58 per cent) directly or indirectly as a result of nutritional deficiencies, infections, epidemics or diseases which attack the body when its resistance and immunity have been weakened by undernourishment and hunger” (Ziegler 2001, p. 5).

The researchers explain that the environmental toll of population growth and rising affluence seemingly binds humanity in a common fate, but, as the tragedy of the commons suggests, countries do not share the costs and benefits associated with the exploitation equally. For instance, Sudan is one of the countries populations of which died of widespread famine and destitution (Alemu 279).

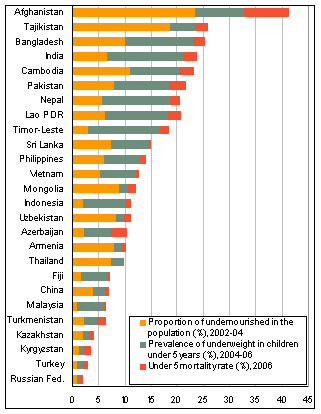

The latest US estimate says up to 1.2 million people now face starvation in the south of the country – many more than previously thought. The dramatic increase has prompted the humanitarian aid to call for an unprecedented relief operation to target those most at risk in several areas it describes as famine zones (Ziegler 7, See Appendix Table 1).

Famine is a direct result of the decreased world’s food particularly impressive after World War II. In the thirty-five years from 1950 to 1985, world grain harvests increased from less than 750 million tons to 1.7 billion tons.

Even though the world experienced unprecedented population growth during this period, the growth in food production was so spectacular that it permitted a 25 percent increase in per-capita food supplies and a corresponding increase in meeting minimum nutritional standards.

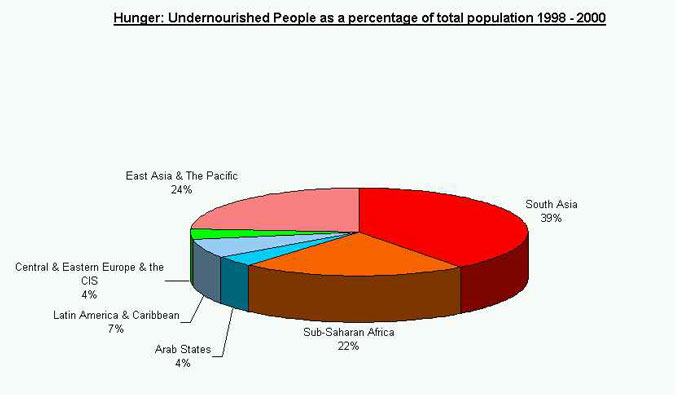

Primarily, these studies concern European countries and the USA but do not take into account Asian and African countries where population growth has a direct impact on famine (Ziegler 7).

As a generalization, population growth accounts for the difference between total and per-capita production of food in developed and developing countries. Africa stands in stark contrast. It was predicted that the population growth would outstrip food production appear more apt than here.

During the 1970s, Africa’s food production increased by only 1.8 percent annually, but its population grew at a rate of 2.8 percent. Starvation and death became daily occurrences in broad stretches of the Sahel, ranging from Ethiopia in the east to Mauritania in the west.

The situation was repeated a decade later when, in Ethiopia in particular, world consciousness was awakened by the tragic specter of tens of thousands suffering from malnutrition and dying of famine at a time of unprecedented food surpluses worldwide.

As population growth has moved hand in hand with desecration of the environment, sub-Saharan Africa has experienced the tragedy of the commons in all of its most remorseless manifestations (David 32; Alemu 279; See Appendix Table 2, 3).

It should be mentioned that the problem of famine as a crisis of entitlement was also examined. Such researchers as David (31) tried to prove that famine has social roots and does nothing with overpopulation. It is possible to agree that soil erosion, desertification, and deforestation are worldwide phenomena, but they are often most acute where population growth and poverty are most evident.

The search for fuelwood is a major source of deforestation and a primary occupation in developing countries (Ziegler 5). Deforestation and soil erosion also occur when growing populations without access to farmland push cultivation into hillsides and tropical forests ill-suited to farming.

It is possible to say that the problem of famine as a result of overpopulation is better examined from the historical perspective as well. Historians pay a special attention to the rate of population and food consumption.

As trends in births, deaths, and migration unfold worldwide into the twenty-first century, demographic changes will promote changes in world politics. At issue is how these trends will affect traditional national security considerations, economic development opportunities, and the prospects for achieving global food security (Ehrlich 98).

Many researchers (Davis, 12; Ehrlich, 211) stress the adverse effects of population growth on economic development. What they often ignore, however, is that the world has enjoyed unprecedented levels of economic growth and unparalleled population increases simultaneously.

Even those countries with the highest rates of population increase are arguably better off economically today than they were at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Declining infant mortality and rising life expectancy coincide with improved living standards throughout the world, even if, ironically, these are the very forces that drive population growth. Some researchers examine the role of politics in famine (Healey 101). Nevertheless, this problems is less examined in comparison with population growth and its impact on food shortage.

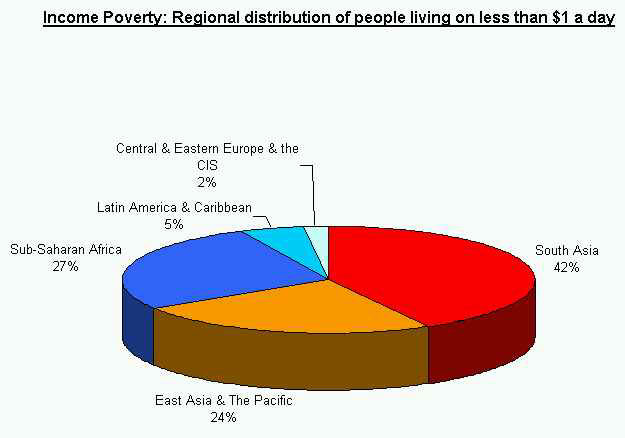

Studies state that population growth contributes to the widening income gap between the world’s rich and poor. It also contributes to lower standards of living for many, as poor people tend to have more children to support than do those who are relatively better off. Furthermore, by depressing wage rates relative to rents and returns to capital. (Osborn 87).

Any of the agricultural products produced in developing countries (such as sugar, tea, coffee, and cocoa) are exported abroad, where they are dietary supplements (with little nutritional value) for the world’s rich.

The problem of overpopulation is possible to illustrate by the fact that there is only about one working-age adult for each child under fifteen in the Third World. It also encourages the immediate consumption of economic resources rather than their reinvestment in social infrastructure to promote future economic growth.

Kenya knows famine. Recorded first in 1884, thereafter in 1928, 1944, 1949, 1981, 1984 and 1997. Each of these years has been severe for our citizens, necessitating the uncertainties and indignity of international food aid. In 1997, close to 5 million tonnes of maize were imported into Kenya. Between 1993 and 1995, maize, wheat, sorghum, millet, rice, beans, beef and milk recorded shortfalls in supply.

Although population growth was, and continues to be, an important factor, a scarcity of pest-free storage facilities, the incidence of crop diseases and the vagaries of weather worsened the level of shortages. The trend will not be easy to reverse. Ireland knew famine.

In the 1850s nearly 1 million emigrated to America. That is not open to Kenyans today—they will not let us in, neither will Europe. Nor would we wish to go. We simply want to be able to eat. It would help if the North ate less and used less energy when they did (Ziegler 8).

To conclude, famine is a complex problem which effects world’s society from ancient time. Researchers point out different causes of this problem, but the problem of famine as a result of overpopulation is better examined. A lot of researchers mention political and social factors but they do not provide deep analysis of these problems and their direct impact on famine around the world.

Excessive population growth doubtless strains the environment and contributes to destruction of the global commons, but excessive consumption is even more damaging. In this respect it is not the South’s disadvantaged four-fifths of humanity who place the greatest strains on the global habitat but the affluent one-fifth in the consumption-oriented North.

Differential fertility rates among various ethnic populations will also have internal and international consequences (Ehrlich 38). In Israel, for example, the Jewish population may one day become the minority, as fertility rates among Arabs and Palestinians within Israel’s borders outstrip those of Israel’s Jews.

Analogous trends are already evident in South Africa, where the white population is expected by the year 2020 to comprise only one-ninth to one-eleventh of the total population compared with the one-fifth it accounted for in the early 1950s.

Works Cited

Alemu, Tadesse “Nutritional Assessment of Two Famine Prone Ethiopian Communities”, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 51 (1997), p. 278-282.

David, A. Famine and the Crisis of Social Order. Blackwell Publishers, 1998.

Ehrlich, P. R. The population bomb. New York: Ballantine Books, 1971.

Fluehr-Lobban, C. and R. Lobban “The Sudan Since 1989: National Islamic Front.” Arab Studies Quarterly 23 (2001), 1-9.

Healey, J. (ed) Foreign Aid and World Debt. The spinney Press, 2000.

Osborn, F. Our Crowded planet. Greenwood Press Reprint, 1998.

Ziegler, J. The Right to Food. 2001.

Appendix