Introduction

Laboratory methods of chemical analysis are widely used to investigate the chemical nature of substances, describe their interactions, and study the processes involved. Strictly speaking, heat is a form of energy transferred between bodies following the thermodynamic heat transfer laws (LT, 2023). One such law is the postulation of the existence of enthalpy, which is the sum of the internal energy of a body and the work done; in physical terms, the change in enthalpy determines the amount of heat that is released in a process at constant pressure (LT, 2023).

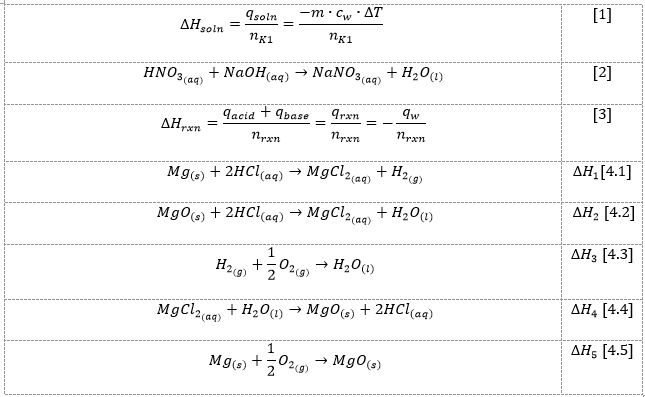

In the present work, the focus was set on the study of thermochemical processes: the work consisted of three consecutive parts in which the heat of solution, the heat of reaction, and the applicability of Hess’s laws to the study of thermochemical reactions were studied. The first part was the study of the enthalpy of solution using the formula shown in [1]. In the work’s second part, the enthalpy was calculated not for an isolated solution but for the chemical process shown in [2]. The formulas of [3] were used to calculate the enthalpy of the reaction. Finally, in the third part of the study, the heat of reactions [4.1]-[4.5] was analyzed using Hess’s law as a guide. Thus, the unified aim of the present work was to practice thermochemical knowledge and calculate the enthalpy and heat of solutions and reactions with increasing complexity in the experiment conducted.

The present laboratory study was based on performing a series of sequential experiments using LabQuest as a key tool for visualizing thermal data. The study consisted of three parts, each differentially investigating heat and enthalpies. The procedure allowed changes from the original methodology guides, including changing the substance from KBr to KI and increasing the time to record the final temperature.

In the first part, it was necessary to prepare the solution initially and then determine the enthalpy of the solution from the temperature difference. Specifically, the calculated amount of potassium iodide (33.2 g) was transferred after exactly four minutes into 100 mL of DI water previously placed in a calorimetric beaker and subjected to initial temperature measurement. Thus, after four minutes, the dry salt was added to the DI water, and the final temperature (horizontal plateau temperature) was measured using LabQuest and recorded in Table 1.

In the second part of the experiment, 50.0 mL of 2.2M nitric acid was transferred to the calorimetric beaker, for which the initial temperature was measured. Four minutes later, a sudden temperature spike was observed when 50.0 mL of 1.9M sodium hydroxide was added to the acid to initiate the neutralization reaction; ten minutes from the start of the process, an increase in the initial temperature was recorded — the final temperature was recorded in Table 2.

The third part of the experiment was of increased complexity and involved a series of sequential reactions. Thus, 30.0 mL of 2M hydrochloric acid was added to the calorimeter beaker, for which the initial temperature was measured. Then, 0.009 g of solid magnesium was added to the acid after ten minutes, allowing the final temperature to be determined using LabQuest and recorded in Table 3. After carefully cleaning the calorimeter beaker, 30.0 mL of 2M hydrochloric acid was transferred back into the beaker, and ten minutes after the initial temperature was measured, 0.0336 g of magnesium oxide was added to the acid, which initiated the chemical process and allowed the final temperature of the reaction to be determined, recorded in Table 3.

Data and Results

In the first part of this work, 33.1903 g of potassium iodide salt was added to 100.0 mL DI water, increasing the temperature from 20.0 °C to 30.0 °C. As shown by the results in Table 1, as well as the demonstration of the calculations in equations [5]-[8], the heat of the reaction was determined to be -5405.5 J, and the enthalpy was determined to be -26.1 kJ/mol.

Table 1: Results of direct measurements and indirect calculations for enthalpy of KI solution.

This table contains the results of direct measurements (first three columns) and the results of calculations (last three columns) to determine the enthalpy of the KI solution.

First, the difference between the final and initial temperatures was calculated:

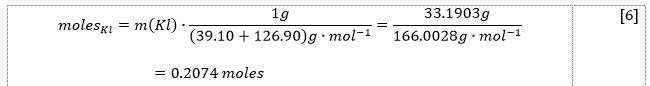

Then, the number of moles of potassium iodide was calculated:

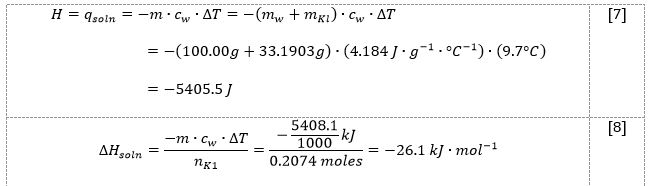

Now, using the formula [1], it was possible to determine both the heat of reaction [7] and enthalpy [8], viz:

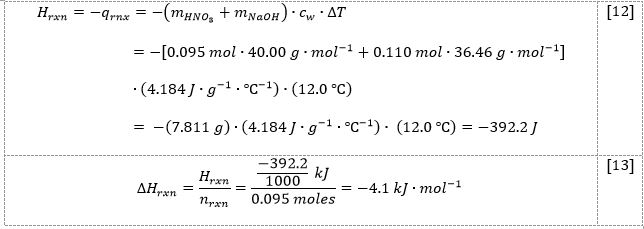

In the second part of this work, 50.0 mL of nitric acid was mixed with 50.0 mL of sodium hydroxide, increasing the temperature from 22.1 °C to 34.1 °C. The limiting reactant of this process was alkali. As shown by the results in Table 2 and the demonstration of the calculations in equations [9]-[13], the heat of the reaction was determined to be -392.2 J, and the enthalpy was determined to be -1.9 kJ.mol-1.

Table 2: Outcomes of indirect calculations and direct observations for the enthalpy of reaction between HNO3 and NaOH.

This table contains the results of direct measurements (first four columns) and calculations (last three columns) to determine the enthalpy of the neutralization reaction between nitric acid and sodium hydroxide.

The first step was to compute the difference between the starting and final temperatures:

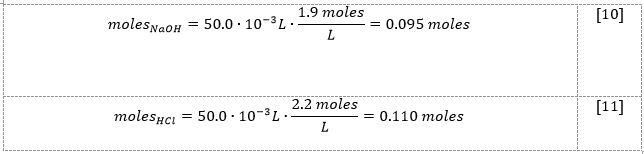

Then, calculations of the number of moles for the base [10] and acid [11] were performed:

From the reaction of [2] stoichiometrically, the number of sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid moles should be equal. Considering the results from [10] and [11], it can be seen that NaOH is the limiting reactant, and hence, this number of moles should be used in the enthalpy change calculation. Then, using the formula [3], it was possible to determine the heat of the reaction [12] and enthalpy of the reaction [13]:

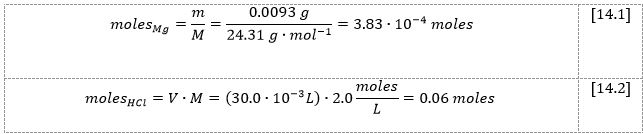

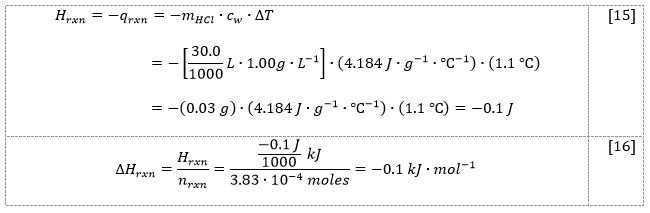

In the third part of the experiment, 0.0093 g of solid magnesium was mixed with 30.0 mL of 2M hydrochloric acid, which caused the temperature to increase from 21.5 °C to 22.6 °C. This process released 0.1 J of thermal energy, equivalent to an enthalpy change of 0.1 kJ/mol. The second procedure raised the temperature from 21.9 °C to 24.5 °C by combining 0.0336 g of solid magnesium oxide with 30.0 mL of 2M hydrochloric acid. During this process, 0.3 J of thermal energy was released, equivalent to an enthalpy change of -0.4 kJ/mol.

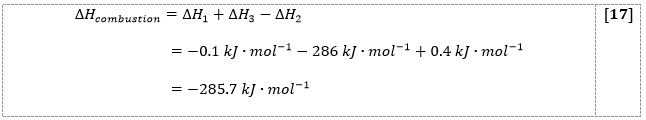

To calculate the entire combustion process, the enthalpy change for the process [4.2] (∆H1 + ∆H3) was subtracted from the sum of the enthalpy change for the reactions [4.1] and [4.3] (∆H1 + ∆H3 – ∆H2), which, given the enthalpy change for water formation equal to (∆H3 = -286 kJ/mol), yielded a magnesium combustion enthalpy change of -285.7 kJ/mol.

Table 3: Results of direct measurements and indirect calculations for sequential reactions using Hess’s law.

The table shows the results of measurements and calculations for two parallel processes. The first six columns contain the direct measurement data, and the last three are the results of the calculations below.

To begin, the difference between the final and initial temperatures for each of the two reactions, [4.1] and [4.2], was calculated:

ΔT4.1 = Tf – Ti = (22.6 – 21.5) °C = 1.1 °C

ΔT4.2 = Tf – Ti = (24.5 – 21.9) °C = 2.6 °C

The mole number calculations were then performed for all reactants in the reaction [4.1]:

From the stoichiometry in the reaction [4.1], it can be seen that the number of moles of hydrochloric acid should be twice that of solid magnesium; in fact, the number of moles of hydrochloric acid is even higher, indicating that the acid was taken in excess. Then, given that nrxn is the number of moles of limiting reactant, the heat [15] and enthalpy [16] for the reaction [4.1] might be calculated using the formula [3]:

Similar calculations were carried out for the reaction [4.2] in which magnesium oxide interacted with hydrochloric acid. The acid was again in excess. Once the enthalpy changes were calculated for the two reactions, Hess’s law for five processes, [4.1]-[4.5], could be applied.

Equation [17] shows the logic of the Hess law calculation, namely:

Discussion

Comparison of the results obtained with literature data makes sense to check the reliability of the conclusions. In particular, for KI, according to Efimov et al. (1979), the enthalpy is about 20.15 kJ/mol, whereas the empirically determined absolute value was -26.1 kJ/mol. The result obtained has a percentage error equal to 29.5%. This implied that the experimental result was 29.5% higher than the value accepted in the scientific literature. Some sources of errors that led to this deviation could have been irregularities in the assembly of the calorimetric setup that led to heat escaping outside the isolated zone, including the assumption that the double-walled Styrofoam cup had ideal thermal insulating properties for the experiment.

In the second and third parts of the experiments, moles were counted to determine the limiting agents. This step was important because the processes involved more of the second substance than was required for the reaction (Sawaki et al., 2020). In other words, some of the substance remained unspent in the calorimetric cup, and accounting for this amount could lead to distortions in the results of enthalpy calculations. Enthalpy, i.e., the real change in thermal energy per mole of a substance, takes into account the number of moles of the limiting agent, and thus, accounting for more of them would lead to potentially incorrect results.

It is also important to discuss the application of Hess’s law to the combustion reaction of magnesium. Specifically, the law postulates that the enthalpy of the entire process is independent of the intermediate points but is determined only by subtracting the final enthalpies from the initial enthalpies (CC, 2021). It followed that there was no point in considering all the intermediate phases of the reaction; however, it was necessary to rearrange the reactions so that this could lead to a pure magnesium combustion reaction in oxygen. After adding the reactions [4.1] to [4.3] and subtracting [4.2] from them (i.e., adding the reversible [4.2]), this yielded a pure solid magnesium combustion reaction. In this case, it was important to consider the available coefficients, the compensating substances on either side of the reaction, and the change in the sign of enthalpy for the reversed reaction.

Several methodological changes were used in the laboratory work. The substance for the first process was changed from KBr to KI, but this did not affect the quality of the results as all data were relevant to KI. In addition, ten minutes was used instead of four minutes to record the final temperature for the second and third parts. This decision was because the temperature continued to rise after four minutes and did not reach a plateau. Since time is not a criterion that affects the quality of the results; increasing it by six minutes improved the results because a more accurate end temperature was used.

Conclusion

In the present work, thermochemical studies were carried out in three parts. In the first part, the enthalpy of the KI solution was determined, which showed an error of 29.5% compared to the academically accepted value. In the second part of the work, the enthalpy was calculated for the chemical interaction between acid and base, where the base was the limiting reactant – the use of formulas allowed the calculation of an empirical enthalpy value for this process. Finally, the third part of the experiment was an extension of the second part, for which Hess’s laws were applied. Specifically, Hess’s law was used for the magnesium combustion reaction, and through careful calculations and correct rearrangement of the reactions, the total enthalpy change of magnesium combustion was calculated.

References

CC. (2021). Hess’s law [PDF document]. Web.

Efimov, M. E., Klevaichuk, G. N., Medvedev, V. A., & Kilday, M. V. (1979). Enthalpies of solution of KBr, KI, KIO3, and KIO4 in H2O. Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, 84(4), 273-286. Web.

LT. (2023). Enthalpy. LibreTexts Chemistry. Web.