Introduction

Human health is one of the world’s most important fundamental human rights. The World Health Organization (WHO) is continually working towards promoting the health of individuals. According to Alzahrani et al. (2019, p.2), health-promoting lifestyle behaviors are actions and beliefs that individuals enforce to stay healthy and prevent themselves from diseases.

Physicians play an essential role in health protection and improvement. They work as caregivers to enhance society’s healthcare and are considered role models in adopting healthy living. As a result, medical experts are influencing the lifestyles of individuals. They are expected to have the relevant information for health-developing concepts and can apply the knowledge in practice.

Medical facilities providing learning environments for students play an informative role in promoting healthy lifestyles in society. The facilities should educate the students on how to protect their health and exhibit an exemplary role in society (Al-Qahtani, 2019, p. 509). In this regard, testing medical students’ knowledge and practicing healthy lifestyles as they continue learning is essential. This report aimed to establish changes in healthy living behaviors and factors affecting such behaviors among medical students from the University of Pretoria over two years.

Literature Review

Many studies examine the awareness and adoption of healthy living habits by medical students. Medical students reported having the most excellent eating habits, according to a study comparing the healthiest lifestyles of senior physicians, residents, and medical students (Wilf-Miron, Kagan, and Saban, 2021, p. 1). Similarly, the medical students had the least emotional stress compared to the two other groups.

Study results revealed that healthy lifestyles among medical students deteriorated as they approached residency. The curriculum of medical schools is effectively integrated to encourage students to lead healthier lifestyles and improve the healthcare system’s effectiveness. The current work provides additional insight into the knowledge and practice differences in healthy living as medical students transition from the first to the second year in college.

Students at medical colleges are prospective doctors and are actively involved in promoting healthy lifestyles. A study by Rahmadhani, Simamora, and Sahadewa (2023, p. 14) showed a significant relationship between healthy living knowledge and healthy living behavior patterns among medical students. The study reported that 78.1% of the students had knowledge of healthy living, and 54.7% had positive attitudes towards healthy living. Among other things not looked at in this study, a healthy attitude is one of the elements that influence healthy living, in addition to knowledge. This study looked at the association between demographic traits and patterns of healthy behavior.

Problem Statement

College students represent a significant proportion of the youth population. Most students in colleges are more prone to unhealthy behaviors because they have more choices in health-related behaviors, including smoking, unhealthy sleeping and eating, increased stress, and failure to exercise, among others. Medical students, as future physicians, study in a risky environment that exposes them to unhealthy living despite receiving training on the importance of health-related behavior patterns.

Medical students’ ill health negatively affects efficiency, quality of patient care, and production. There is limited research on the relationship between knowledge and practice of healthy lifestyle behaviors among medical students. This report established the differences in healthy living among students over two years.

Objectives of the Coursework

The objectives of the report were;

- To establish the relationship between the health behavior of medical students and their demographic characteristics.

- To compare the health-related habits between first- and second-year medical students.

Methods

Dataset

The dataset used in this report was obtained from a Google Dataset search. Luyanda Masilela authors the dataset and represents the wellness practices followed by University of Pretoria medical students. The data was collected over two years and contains baseline health behavior characteristics (in the first year), demographic characteristics, and second-year health behavior patterns.

Lifestyle choices have a critical role in health outcomes. Research establishes a significant association between examining healthy lifestyle factors and health promotion. For example, a study by Hoying et al. (2020, p. 50) showed a significant correlation between healthy lifestyle behavior among college students and depression and anxiety.

Though individual healthy behaviors have been studied extensively within many disciplines, researchers have recently begun to harness empirical insights from multiple health behaviors simultaneously (Mollborn, Lawrence, and Saint Onge, 2021, p. 396). Health lifestyle datasets provide a perspective on understanding social behavior among individuals. There is a shortage of evidence concerning healthy lifestyle behavior patterns among college students. Therefore, this report used the medical students’ healthy behavior dataset to establish empirical evidence in healthy living improvement among medical students with additional knowledge acquisition.

Table 1: Health Behavior Dataset for Medical Students from the University of Pretoria

Table 1 shows different variables in the dataset, including demographic features such as age, race, and body mass index (BMI). The health behavior variables include smoking, alcohol score, physical activity index (KazariFitIndex), diet quality score (Reap), sleep quality score (PSQscore), and the rest as clustered risk factors.

Analysis and Results

Dataset Preparation

The dataset was downloaded from the Google Dataset search in a comma-separated values (CSV) file, uploaded to Google Drive, and then imported to Google Colab, running on Python 3.9 for analysis. After uploading the data and viewing it in Colab, the dataset did not have missing values, and thus, no cleaning was needed.

Exploratory Data Analysis

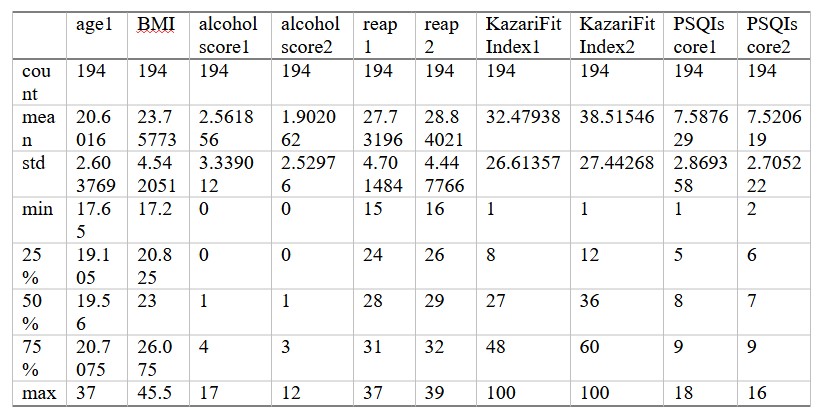

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows a significant decline in the mean alcohol score between year one (23.757732) and year two (2.561856). This implies that medical students reduced alcohol intake in their second year in college. However, the mean diet quality score increased from 1.902062 in the first year to 27.731959 in year two.

There was a vast improvement in dieting among the medical students as they progressed from their first year to their second year of learning. Similarly, there was an improvement in physical activity among the students from 28.840206 in year one to 38.51546 in year two. The medical students registered a slight fall in mean sleep quality score (PSQ) from 7.587629 in the first year to 7.520619 in year two.

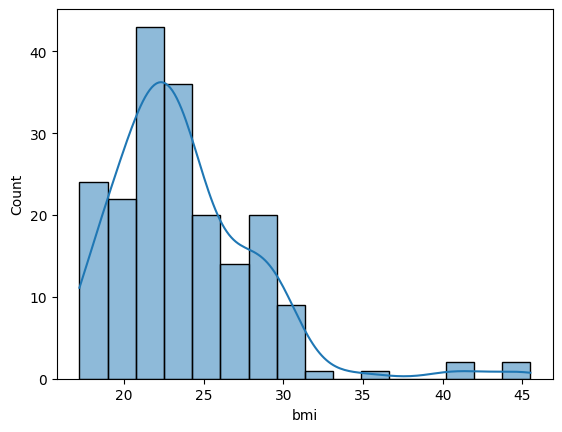

Figure 1 shows that BMI data from medical students are not normally distributed. The data points are skewed to the left. The data contains several outliers, including 35, 40, and 45, represented by the bars far from the rest (Figure 1).

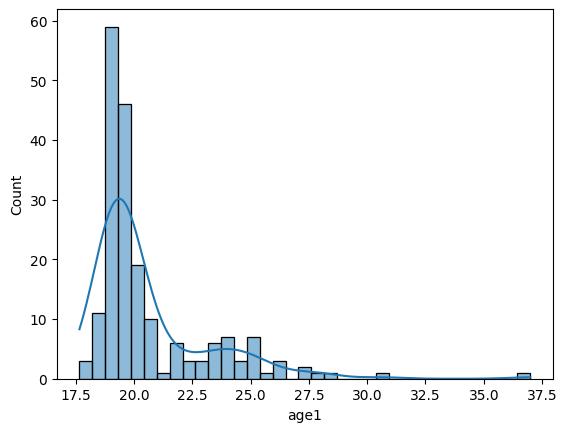

Figure 2 shows that the age dataset has outliers such as 30, 32.5, 25, and 37.5. The data is skewed to the right and non-normal.

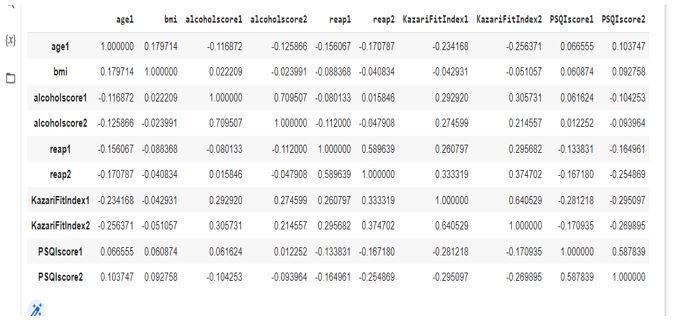

Table 3: Correlation Analysis

Table 3 shows the relationship between health behavior and demographic variables. For instance, a weak negative correlation exists between age and physical activity index (-0.234168, -0.256371) among year-one and year-two medical students, respectively. Physical activity and diet quality show a weak positive relationship for year-one (0.260797) and year-two (0.374702) students. Sleep quality (PSQscore1) is negatively related to diet quality (reap1) (-0.133831).

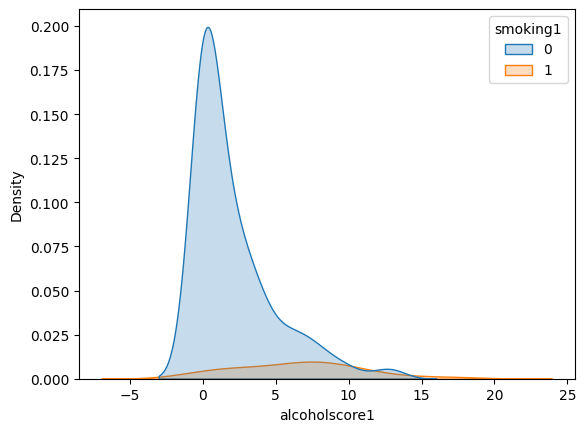

Figure 3 shows a kernel density that shows the alcohol scores for the smokers were distributed normally. However, the scores for the non-smokers are slightly skewed to the right and are sharply pointed.

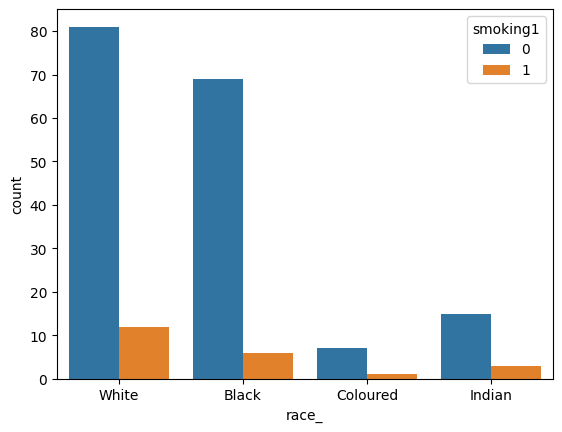

Figure 4 shows that the highest number of smokers and non-smokers was among the white medical students. However, the non-smokers outnumbered the smokers across all races. Black students had the second largest number of smokers, followed by Indian students, with colored students having the lowest number of both smokers and non-smokers.

Data Modeling and Visualization

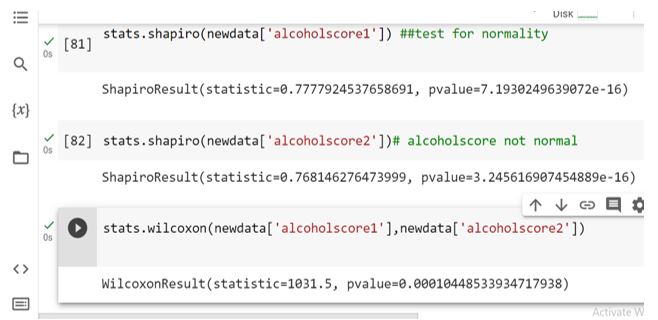

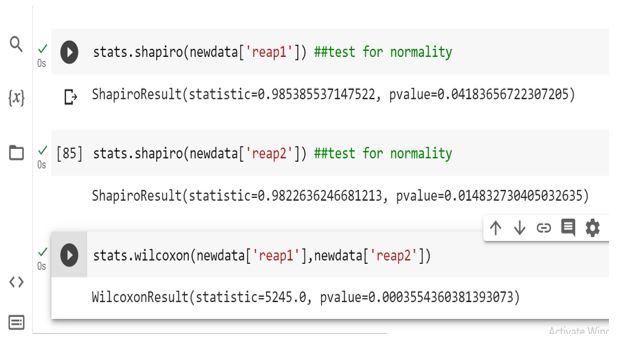

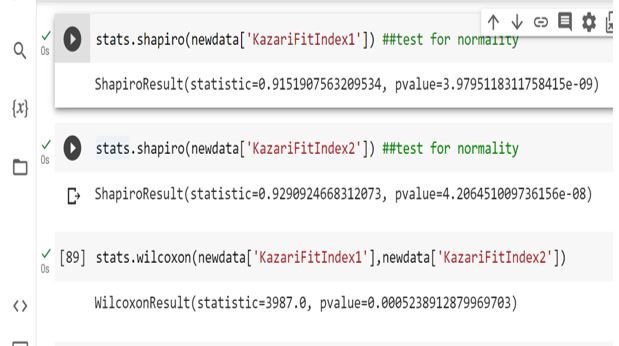

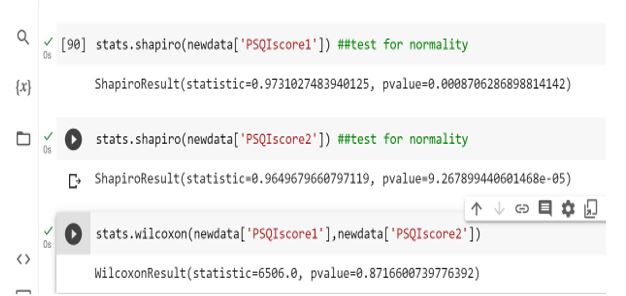

The report employed the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test for significant mean differences between different variables when the medical students were in the first and second years of their training. The univariate statistical test is a non-parametric version of the dependent sample t-test. The variables tested for mean score differences over the two years included alcohol score, reap, KazariFitIndex, and PSQScore.

The four pairs of variables violated the normality assumption required to perform a t-test (p-value<0.05) (Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8). As a result, a non-parametric test was used. Results show a statistically significant means score difference for alcohol, reap, and KazariFitIndex for the two years (Figures 5, 6, and 7). However, PSQScore was statistically not different when the medical students were in the first year and the second year (Figure 8).

Evaluation

The findings in this report show that students are responsible for improving their health within two years at the university. The improvement in alcohol use, physical activity, and diet quality among these students could be attributed to increased awareness about their health and health responsibilities over the two years. In their study, Rieder et al. (2021, p. 1) support these findings by stating that exposing students to structured health lifestyle programming or an education framework may positively improve their behaviors. The study used a logistic mixed-effect model for the analysis.

However, a study by Dörtkol and Özdemir (2021, p. 20) among medical students to evaluate the trend in healthy lifestyle behaviors showed that the behaviors did not improve with the education received. The results showed that the first-year students had significantly higher physical activity scores, interpersonal relationships, and spiritual growth than their counterparts in the sixth year. They used the Chi-Square test, the Bonferroni test for group comparison, and the Shapiro-Wilk Test for normality. Borillo, Tamanal, and Kim (2020, p. 999) argue that school education and peer support are critical factors that help students develop positive behaviors and enhance adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle factors. This report shows that Pretoria University medical students reported a significant improvement in healthy living for two years.

Limitations and Challenges

The major challenge was obtaining a dataset that would provide a current health-related problem for the data analytics report. However, significant research on different data sites helped overcome the challenge and obtain a downloadable dataset on health behavior. The health lifestyle scores from the data are self-reported and susceptible to social desirability bias. The lifestyle screening tool makes these scores meaningful by converting them to a measurable format for analysis.

Conclusion

A data science report comprises various sections, making it progressive. The report should start by defining the problem and identifying some of the objectives under study. Providing background information about the research problem is critical in such a report. It is essential to assess past research and existing gaps in the problem under study. I have learned that exploratory data analysis provides significant insight into the analysis and results of the problem. There are many modeling methods to choose from, but they all depend on the distribution of your dependent variable and the scale of the variables under investigation.

Reference List

Al-Qahtani, M.F. (2019). ‘Comparison of health-promoting lifestyle behaviors between female students majoring in healthcare and non-healthcare fields in KSA’, Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 14(6), pp.508-514. Web.

Alzahrani, S.H. et al. (2019). ‘Health-promoting lifestyle profile and associated factors among medical students in a Saudi university’, SAGE open medicine, 7(1), pp. 1-7. Web.

Borillo, C.J., Tamanal, J.M. and Kim, C.H. (2020). ‘Determining the cut off score of the healthy lifestyle screening tool among high school students’. Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 10(2), p.92-101. Web.

Dörtkol, A. and Özdemir, L. (2021). ‘Evaluation of healthy lifestyle behaviors and related factors in medical students’, Cumhuriyet Medical Journal, 43(1), pp.20-30. Web.

Rieder, J. et al. (2021). ‘Trends in health behavior and weight outcomes following enhanced afterschool programming participation’, BMC public health, 21, pp.1-12. Web.

Wilf-Miron, R., Kagan, I. and Saban, M. (2021). ‘Health behaviors of medical students decline towards residency: how could we maintain and enhance these behaviors throughout their training’, Israel Journal of health policy research, 10(1), pp.1-8. Web.