Introduction

Transitional nursing in oncology is an under-researched theme, which, nevertheless, needs to be addressed. While some of the researches are primarily focused on transitional nursing practices with no specifics, others provide an insight into the transitional care of cancer patients and cancer survivors. For example, McCorkle et al. (2009) conducted a research to address the poor quality of life linked to gynecological cancers. The results demonstrated that specialized care that was provided for participants by an oncology Advanced Practice Nurse had improved their life.

Although the quality of life was not affected, participants experienced less uncertainty and were less stressed compared to the control group (McCorkle et al., 2009). National Research Council (2005) presents another strategy, named the shared-care model, that is somewhat similar to the one mentioned above. As stated in the research, primary care physicians or professionals in end-of-life care have the potential to provide the needed transition; the model depends on professional training and appropriate remuneration, state the authors.

Yarbro, Wujcik, and Gobel (2016) discuss several models of survivorship care: disease-specific, consultative, collaborative practice, and transition to primary care. For transitional nursing, two of them are eligible: consultative model suggests that the patient remains under the care of their oncologist, but the nurse provides a one-time consultation to create a survivorship care plan; transition to primary care model suggests transitioning survivors to their PCP after the treatment is completed (Yarbro et al., 2016).

Bleyer, Barr, Ries, Whelan, and Ferrari (2016) provide different transitional care models for nurses that care for adolescent cancer patients: adult practitioner model (patient education and health promotion – in adult care facilities), resource model, switch model, and comfort model. Schwartz, Hobbie, Constine, and Ruccione (2016) point out that the transitional period is especially difficult for adolescents because young adult survivors “encounter a greater difficulty obtaining [health insurance]” (p. 422). As can be seen, some progress is made in nursing transition in oncology, but it needs further investigation to understand what strategies are the most efficient both for patients and for nurses.

Methodology and Design of the Study

A descriptive, applied, quantitative, empirical research was designed to evaluate the problem. The research design was based on random sampling, whereby both oncology nurses and patients were randomly selected from several local hospitals or other clinical units. It was decided that random selection from different medical facilities has more potential to provide valid and interesting findings: first, it was most likely that nurses and patients from different medical facilities would not interact with each other, which can lead to distorted results. Second, transitional strategies in oncology can be seen and implemented differently at different facilities.

A nursing professional, who is not among the authors of the study, were recruited to ensure that the number of potential bias could be reduced.

It was decided that a questionnaire method is not suitable for the study because questionnaire answers can provide poor response rates. Therefore, qualitative research interviews (personal, face-to-face interviews) were used in the study as a method of data collection. There are several reasons why this method was chosen:

- personal interviews cover the factual and the meaning level

- the study must evaluate participants’ experiences and suggestions

- interviews can provide more detailed information compared to questionnaires

- interviews allow the author to work with the participant directly

- interviews are resource-intensive

- interviews ensure that participants of the study are not influenced by other parties during their response (compared to questionnaires and phone/mail interviews)

- interviews allow the author to notice behavioral changes in the participant that might indicate the validity or the invalidity of the response

- unlike questionnaires, interviews require the participant to be attentive to all questions (enhances comparability because questions cannot be overseen)

- face-to-face interviews are more appealing to interested participants than questionnaires

All units and patients were contacted after the administration of the medical facilities had agreed to give us access to them. The potential participants received a personal letter with an explanation of the study and some information about its author. Contact numbers (e-mail/phone number/skype/Viber) were given to the participants included in the sample. Before the interviews, all participants who agreed to take part in the study provided written consent. Underage participants consulted with their parents who provided written consent as well.

Each member of the sample size was approached by the author for a personal interview. Those participants who refused to take part in the study were approached as well to collect data and understand the reason behind their refusal.

Unstructured informal interviews were chosen as tools to conduct the study. During these interviews, participants have the time to reflect upon the questions and explain their feelings and answers to the interviewer. This type of interview can help the author understand what opinions the participants have on a specific issue (transitional care and transitional strategies in oncology), if they are satisfied with the existing strategies, what changes they would suggest.

It should be noted that personal interviews are time-consuming and costly (compared to questionnaires).

Sampling Methodology

Simple random sampling was used to create the sample size. The advantage of this approach is that it is an unbiased selection where all units of the sample size have the chance to be selected (Gerrish & Lathlean, 2015). A random sample can be selected via a statistical software package. Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that the bigger the sample size is, the better the sample representativeness (Gerrish & Lathlean, 2015).

In this study, two samples were used: oncology nurses that work with transitional patients and patients that have experienced a transition from one unit to another (or from a medical facility to their dwelling unit). Cancer survivors were also included as participants who have experienced several transitions during their treatment.

Necessary Tools

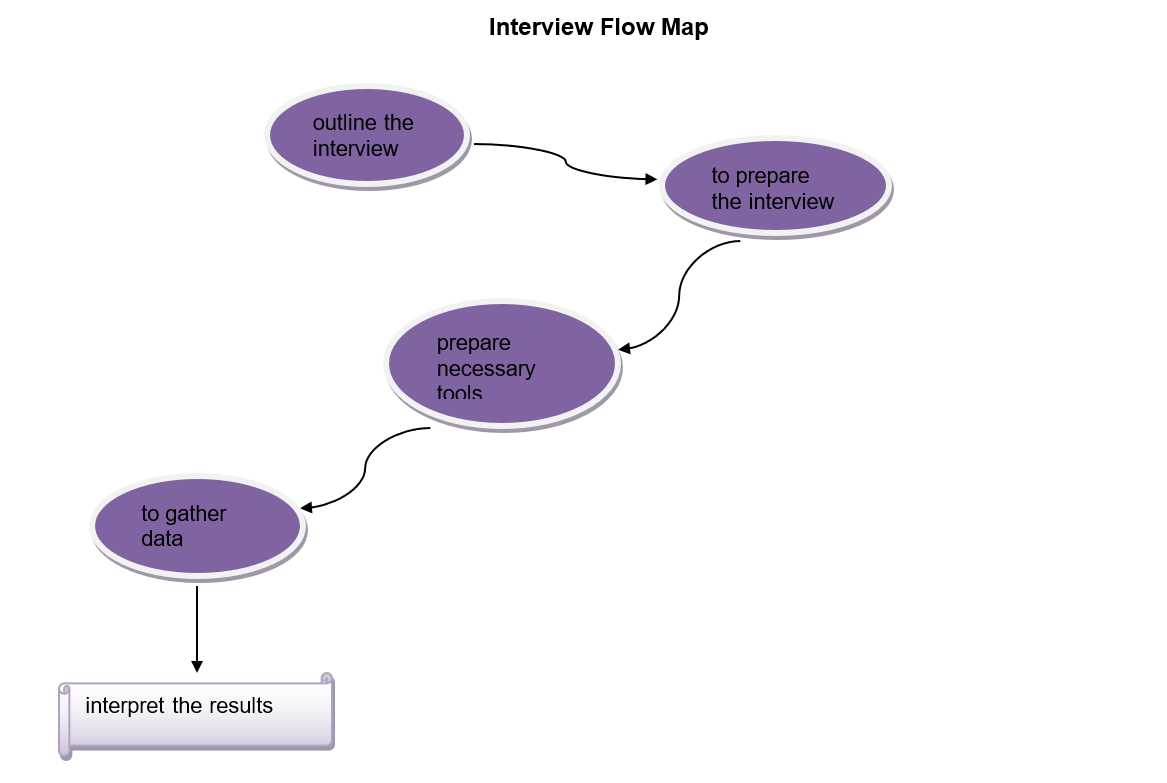

Various tools are needed to conduct valid personal interviews. First, the interviewer needs to be qualified for the interview (should be familiar with the issue, tolerant, critical, and reflective). Second, the interview should be outlined at least partially to understand what questions and topics need to be discussed (e.g. feelings, behavior, opinions, other issues linked to the main one, etc.). Controversial matters should be avoided if not crucial for the research.

Once an outline of or a guide to the interview is completed, the interviewer will need transcribing tools as well (notes, audio recorder, video camera, etc.). If audio recorded is used, it needs to be checked during the interviews to ensure that it is working. Any observations made during the interview are written down as well. After all the data is gathered, the researcher can interpret it.

Interview Flow Map

References

Barr, R., Ries, L., Ferrari, A., Whelan, J., & Bleyer, A. (2016). Adolescent and young adult oncology: Historical and global perspectives. New York, NY: Springer.

Gerrish, K., & Lathlean, J. (2015). The research process in nursing. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

McCorkle, R., Dowd, M., Ercolano, E., Schulman‐Green, D., Williams, A. L., Siefert, M. L., & Schwartz, P. (2009). Effects of a nursing intervention on quality of life outcomes in post‐surgical women with gynecological cancers. Psycho‐Oncology, 18(1), 62-70.

National Research Council. (2005). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Schwartz, C. L., Hobbie, W. L., Constine, L. S., & Ruccione, K. S. (2016). Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. New York, NY: Springer.

Yarbro, C. H., Wujcik, D., & Gobel, B. H. (2016). Cancer symptom management. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.