Recession

A “recession” is the period during which economic activity is declining. A recession is said to occur when “real gross national product declines for two or more consecutive quarters”. Although there is no political or economic benchmark for assessing the recessionary trend, the National Bureau of Economic Research declares the recession, and the major test in this connection is historical. As production declines during a recession, business profits drop and unemployment rises. The increase in unemployment generally lags behind the change in output; most businesses are reluctant to lay off or fire workers. The recession ends with the trough that is the month when economic activity is at the lowest (Wonnacott & Wonnacott, 1979).

45° Line

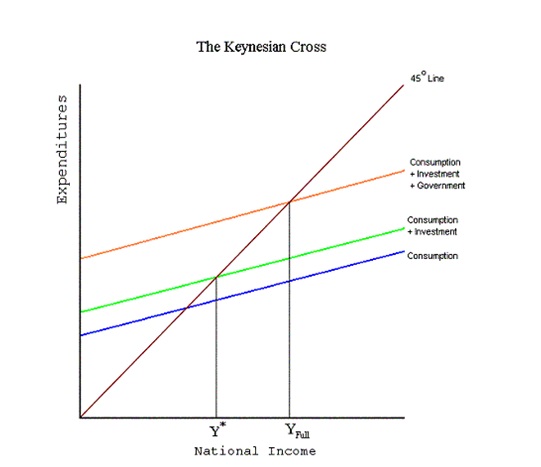

In order to understand the short-run economic equilibrium, it is essential to know the factors, which influence the economy. According to Keynes the marginal propensity to consume, autonomous and unstable investment and liquidity traps have a significant influence on an economy. The Keynesian cross or the 45° graph shown above will illustrate this point. While national expenditure is represented in the vertical axis, the horizontal axis represents the national income. The 45° line contains points at which national income equals national expenditure. Therefore, the assumption is that the long-run economic equilibrium will lie along this line. The consumption function is indicated by the curve sloping upwards.

Even when there is no income, people tend to spend out of their savings. With the increase in their income, people tend to spend more and the spending will be directly proportional to the increase in income. This makes the consumption function intersect the 45° line at some point. At a certain point, which will lie right to this intersection with more income, people will save more than what they spend and the savings will be converted into investments in businesses. The point to note here is that the amount of investment will not depend on the interest rates or even on the amount of savings. As a result, it can be stated that the shift in consumption upwards decided by the autonomous amount of investments by the businesses determines the functions of consumption and investment. The economy reaches equilibrium when the consumption and investment functions intersect at some point in the 45° line (Sherk, 2002).

Macroeconomic Theory

During a period of recession, it is for the government to step in and increase the effective demand. The additional spending by the government would result in an increase in the national income and a full-employment level. In the graph, it is shown as consumption + investment + government. The action of the government would mean freeing the unspent savings and putting them back into the economy. This would raise the output and income levels. This is identified by Keynes, that demand would create its own supply.

The government intervention for increasing the aggregate demand may take the form of changes in the fiscal policy or amendments to monetary policy. For adopting a changed fiscal policy, the government may have to involve itself in large spending without any corresponding increase in taxes. This is called “deficit spending”. The government can resort to the issue of bonds, tap the unspent savings, and put them back into the economy. The alternative is to use the monetary policy to give stimulus to the economy. It amounts to print the money for generating increased demand. However, Keynes believed that monetary policy might not be as effective as fiscal policy. This is due to the reason that with the fiscal policy the government can expect the people to spend the money introduced in the economy, whereas printing and circulating new money would encourage some individuals to hoard the new cash and the banks would tend to keep excess reserves without circulating it in the economy. This would make the new money also be stuck in the liquidity trap. When the government decides to stimulate demand by increasing the government expenditure, the economy would get a boost more than the initial government expenditure due to the “multiplier effect”.

Thus, Keynesian economics supports the theory that the aggregate output in an open economy is comprised of aggregate private-sector consumption. The output is also influenced by the increase in the private sector investment and aggregate government consumption. The investment and aggregate trade balance play a large role in determining the output of the economy. An increase in the government consumption and investment would increase the output, which is more than the investment and consumption of the government and this phenomenon is known as the multiplier effect. “The basic concept of the Keynesian multiplier is that an increase in fiscal expenditure contributes to multiple rounds of spending which could finance itself thereby ensuring higher output and increased employment”(American Chronicle, 2009).

Stimulus Plan and the Impact on the Recession

The stimulus packages appear to depend on the Keynesian macroeconomic analysis, which has been proved an indispensable tool of economic policy. The utility of this economic model has been increasingly felt after Hicks (1937) has developed the IS-LM model, which represents investment saving and liquidity-money supply relations respectively. The specialty of this model is that it combines equilibriums in the goods and services market (IS) and financial markets (LM). This leads to the establishment of an equilibrium level for demand in the economy during the long run although some positive impact can be expected in the short run.

Following the Keynesian theory, the stimulus packages are expected to have short-run macroeconomic impacts of stimulating the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employment by adding to aggregate demand. The increase in aggregate demand will boost the utilization of labor and capital, which would otherwise remain unused due to recessionary trends of the economy (Economist’s View, 2009). This follows the macroeconomic theory explained using the 45° line were due to shifting in the consumption upwards due to the autonomous investments from the stimulus packages would result in the consumption and investment meeting the 45° line at a certain point to bring the economic equilibrium. The increased government expenditure with the stimulus packages under the changed fiscal policy would increase the output and income levels in the short run and bring the economy back from the recession. However, in the short run, there are uncertainties surrounding the expectations that the stimulus plans would result in positive improvements in the economic situation, though some relief can be expected due to increased aggregate demand. Therefore, there are criticisms leveled against the real utility of stimulus packages in arriving at a short-run economic equilibrium.

References

AmericanChronicle, 2009. The Global Economic Crisis and the Resurgence of Keynesian Economics. Web.

Economist’sView, 2009. Estimated Macroeconomic Impacts of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Web.

Sherk, J., 2002. The Fall of Keynes. Web.

Wonnacott, P. & Wonnacott, R., 1979. Economics. Tokyo: McGrawhil Kogakusha Ltd.