Introduction

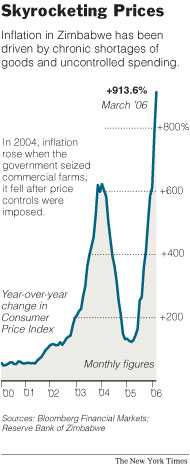

Inflation is one of the main problems in third world countries. The article describe the situations in Zimbabwe and evaluates the impact of inflation on the economy and common citizens. In 2008, Zimbabwe becomes a leading country with an “annual inflation rose this month to 1,063,572 percent” (Shaw 2008, see Figure 1). The situation in Zimbabwe is complex and is caused by different economic factors. On the one hand, the distribution of goods is a vital matter.

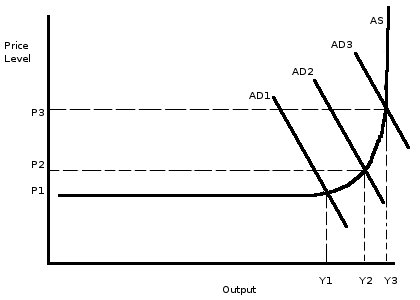

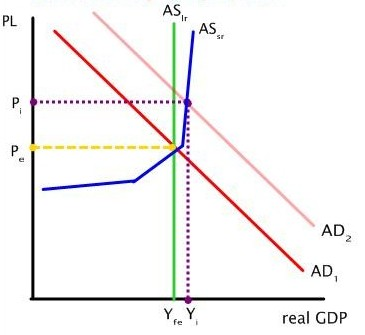

The more inflation grows, the more inequitable becomes the distribution of goods. As prices rise, people with low incomes, or those with fairly rigid incomes which do not respond to higher prices, obtain a declining proportion of the limited supply of the goods made available in the war or postwar period. Inflation also increases the cost of the war and to that extent adds to the burden of the public debt, thus imposing increased sacrifices on taxpayers today and in the future (see Figure 2,3).

Main body

In Zimbabwe, the national-average real wages are raised well above their historical trends, but faster inflation has reduced real wages back to trend levels. Thus the high-wage policy seems not to have brought lasting benefits to employed workers, while it does seem to have reduced employment opportunities for others. Those deprived of access to formal jobs were forced to work in the informal sector and as communal farmers, so the policy actually lowered wages for those activities in which a majority of Zimbabweans are employed.

Taking into account the information discussed in the article, it is evident that a rise of prices induces an expansion of total output. in their turn, production facilities are redistributed and relocated in response to price increase which influences final purchasers. “The economic decline has been blamed on the collapse of the key agriculture sector following the often violent seizures of farmland from whites” (Show 12008). Recent theories of inflation suggest a negative relation between the acceleration of inflation and the output gap: the larger the gap between potential and actual real output, the smaller is the acceleration of inflation (Glanville 43).

Since shortages are unlikely to account for a catastrophic inflation, the great danger lies not in supply but in demand. Once inflation has progressed beyond a certain point, the advance continues not in arithmetic but in geometric progression. When prices rise 5 to 10 per cent per year, the public do not change their buying habits drastically; but once the rise is 25, 50, or 100 per cent per year, they prefer to hold goods rather than money.

Every citizen senses that delay is fatal: the longer he waits the more he will have to pay. Economists generally assume that, as output rises, in the short run costs will rise more and more. At early stages, when unemployment is high, the increase of prices will be moderate. But as output expands, wage rates rise and, in a war economy, taxes increase and bottlenecks begin to appear and to make themselves felt (Glanville 41).

The fiscal variable — government expenditure changes — has a significant positive effect on inflation and nominal income, although this influence is more reduced in some variants, especially when the monetary base or the lagged dependent variables — past inflation and past nominal income changes — are taken into account simultaneously. The theoretical analysis indicates three channels through which world inflation affects domestic inflation: the trade balance multiplier, the balance of payments or monetary effect, and a direct price effect through the supply side.

Zimbabwe is an exceptional case with 165,000 percent inflation a year. he main causes of this inflation are intrusion of the USA and the European Union in national policy of Zimbabwe and its economy. The case of Zimbabwe showst hat tncontrolled prices may well result in the movement of labor and capital to industries which can be dispensed with in wartime. And there is a further reason why, the government should not rely on price movements alone to obtain the optimum allocation of resources: the response to rising prices at best is slow and unpredictable (Glanville 48). In response to higher prices, then, labor, capital, and raw materials are shifted.

Allow the price of taxi fares to rise and more workers will become taxi drivers, even though in wartime it is preferable that workers move into munition industries rather than into luxury trades. it is predicted that “The crunch is going to come when local money is eroded to the point it is no longer acceptable” (show 2008). Society can set up certain social objectives in both wartime and peacetime. It may ask for a war output equal to two-thirds of national output; or, in the postwar period, for expenditures on housing, schooling, and other social services of one-fifth of national income.

Conclusion

In sum, there is a correlation between national policies and international support from other countries which has a great impact on inflation rates and standards of living. Under abnormal war or immediate postwar conditions, freedom in commodity markets will be accompanied by price disturbances, and these in turn will induce a distribution of labor and capital which will interfere with the attainment of these objectives.

Works Cited

- Glanville, A. Economics From a Global Perspective. Glanville Books, 1997.

- Shaw, A. Zimbabwe Inflation now Over 1 million Percent. 2008. Web.