Introduction

Acromegaly is a medical complication characterized by excess secretion of a Growth Hormone. Growth in human beings is facilitated by this hormone. Acromegaly term is borrowed from Greek word akros– implying extremities and megas- meaning enlarged or big. The term was introduced by Pierre Marie, a neurologist from France in 1886 (Cahynur et al. 2011). The following diagrams show the effect of acromegaly (Acromegaly 2011).

After puberty, excess secretion of the hormone results in enlarged soft tissues and other related medical complications. The common etiology is the pituitary adenoma which increases Growth Hormone production and increased IGF-I concentration in serum. Acromegaly, patients are described by overgrowth in soft tissue and in the limbs. Other complications include headache, visual defects, asthenia and sweating. During the later stages, the condition is characterized by the increased size of the head and limbs. Acromegaly patients’ facial appearance is coarse and thickened (Chason, Leselbaum, Blumberg & Schaison 2000). They have an enlarged nose, protruded mandible, skin thickening and may have splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and enlarged kidneys. When untreated, acromegaly may turn deadly. It is a treatable condition for most patients, especially when diagnosed early. Due to its sneaky onset, it is often either misdiagnosed or not be diagnosed early. The condition is approximated to affect over eighty five thousands adults in US and Europe (Antisense Therapeutics, 2011).

This paper delineates acromegaly, its epidemiology and aetiology, diagnosis, treatment management and lastly, presents the current implications about acromegaly.

Epidemiology and Aetiology

Acromegaly is described as a rare condition. Its prevalence is approximated to be 60 cases per million with incidences of approximately 4 cases per million. 99% acromegaly condition is a consequence of benign adenoma in the pituitary gland caused by monoclonal expansion of somatroph cells. Statistics approximate that 40% of somatotrophinomas are due to mutation in the GNASI gene (gsp oncogene) (Cahynur et al. 2011).

Other causes of acromegaly in adults may be due to ectopic secretion of GH- releasing hormone or GH from carcinoid tumors or tumors of the hypothalamus, pancreas, lung and adrenal glands. Macroadenomas prevalence is higher than Microadenomas. Recent research indicated a prevalence rate of up to 130 cases per million to 1000 cases per million for biochemical acromegaly (Murray & Melmed 2008). However, the prevalence appears to be distributed equally among both sexes with a mean age approximated to be 44 years. More so, the condition has been recorded in all stages of life; starting from infancy through childhood to old age. The average delay in diagnosis is due to the duration symptoms take to manifest, and it is said to be around 8 years (Holdaway, Rajasoorya, Gamble, & Gamble 1999).

Pathology

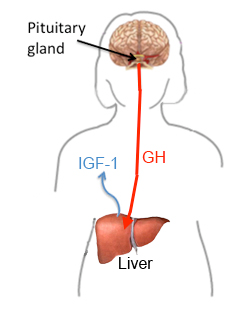

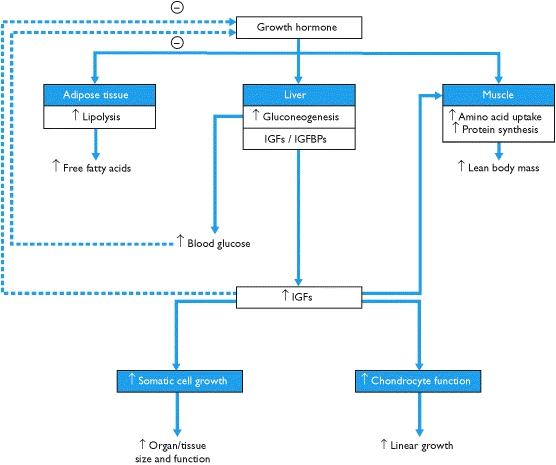

Acromegaly condition as mentioned above occurs due to over secretion of GH in the pituitary. The pituitary gland also secretes other important hormones in the body. Such hormones include those involved in reproduction, metabolism and growth and development. GH regulates growth of the body. Metabolic pathway involved in the secretion of GH hormone begins from the brain in the hypothalamus. Hypothalamus secretes hormones, which regulate the pituitary. This hormone is referred to as Growth Hormone releasing Hormone (GHRH). The hormone stimulates the pituitary gland to secret GH: “secretion of GH by the pituitary into the bloodstream, in turn, stimulates the liver to secrete an insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)” (National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Services, 2006, p.1&2). This hormone is responsible for tissue growth in the body.

Hypothalamus also secretes the somatostatin hormone. This hormone inhibits GH production and releases: “GHRH, somatostatin, GH and IGF-I levels regulate each other through certain conditions such as sleep, exercise, stress, dietary and blood sugars levels” (Levy, 2004, p. 52). If one of the systems malfunctions; it alters the other mechanisms resulting in an increased level of GH, subsequently, IGF-I. As described above, Secretion of growth hormone is regulated by factors involving the interaction of somatroph- cells. Any genetic changes in somatroph cells bring about chromosomal instability and epigenetic alterations (Levy 2004).

Over 90 % of acromegaly patients are diagnosed with a benign monoclonal GH- secreting pituitary adenoma. This adenoma is surrounded by non-hyperplastic pituitary tissue. Clinical manifestations depend often, on the location of the tumor. For example, a tumor in the upward, will put pressure on the optic nerves causing visual complications. It is important to note that pituitary tumors only happen self-generated and are inherited from ancestors (Reid 2009). They only arise due to mutation change in a sole pituitary cell resulting in increased “cell division and tumor formation” (Reid et al., 2009). Most of the mutations are post-birth and mainly on the gene that controls chemical signals’ transmission in the pituitary cells. The alteration permanently switches on the cell, making it divide and secrete GH. Research is being carried out on the events that lead to disordered pituitary cell growth and the overproduction of GH (Hurley & Ho 2004).

Rarely is acromegaly caused by non-pituitary tumors. Non-pituitary tumors include tumors in the lungs, abdomen, pancreas and other parts of the brain. Research has indicated that the tumors can also result in high GH levels either through secretion of the hormone themselves, or produces GHRH hormone responsible for pituitary stimulation to release GH. Surgical removal of these tumors causes a decrease in GH levels, and so, improved acromegaly symptoms. It is common for patients with non-pituitary tumors to have enlarged pituitary. This can be mistaken for a tumor. Therefore, physicians should analyze carefully pituitary before performing any surgery (Melmend 2006).

The clinical manifestations of acromegaly include are acrawl overgrowth, jaw prognathism, swelling of the soft tissue, and arthralgias. Other symptoms include pituitary enlargement, visual defects, headache, visceromegaly of the tongue, salivary glands, liver, kidney, spleen, thyroid gland and prostrate (Gordon, n.d.). It may also affect somatic systems including the thickness of soft tissue, gigantism, and proximal myopathy (Chanson et al. 2009). The condition may also affect the endocrine and metabolic systems such as menstrual abnormalities, galactorrhea, hyperparathyroidism, pancreatic islet cell tumors and thickened skin, deepening of the voice due to enlarged sinuses and vocal cords, Fatigue and weakness, decreased libido and erectile dysfunction (Antisense Therapeutics, 2011). Other common problems associated with acromegaly include diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases, colon polyps, and arthritis (National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Services, 2006, p. 3).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is done mainly through recognition of the somatic features. Blood tests include measuring GH level to check whether it is elevated. The test must be repeated since GH secretion in the pituitary is known to be in impulses because its secretion varies from time to time. It is common to diagnose a healthy person with increased GH or acromegaly patients with normal GH levels. Accurate results are obtained only when GH tests are done under conditions known to suppress GH secretion (Melmed et al. 2009).

The most common method used by physicians is an oral glucose tolerance test. Normally, intake of 75-100g of glucose solution should lower blood GH levels to less than 1ng/nm in healthy individuals. Those with GH overproduction have shown this suppression. This method is highly reliable in confirming acromegaly diagnosis (Levy 2004).

After diagnosing using measuring GH or IGF-I levels, the condition is confirmed using a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pituitary. This is mainly to locate and check the size of the tumor responsible for GH overproduction. This method is a very sensitive imaging technique. Computerized tomography (CT) scans can also be used in the absence of MRI. A perfect example is for acromegaly patients with implants containing metals such as pacemakers. Such patients may not use MRI scans due to the powerful magnets contained in the scan. Where the head scan indicates no presence of such tumors, the physician should check for pituitary ectopic tumors in the abdomen, pelvis, or in chest using a CT scan and examining GHRH I levels in the blood. It is rare to find a tumor secreting GH that cannot be detected even with sensitive MRI scans (National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Services, 2006).

Treatment

Acromegaly treatment is very challenging. Most patients fail to achieve normalization of IGF-I serum concentrations even with the multimodality therapy approach. The main goal for treatment is to minimize excess hormone production to a normal range. Secondly, to release pressure the growing tumor could be exerting on the surrounding brain areas. More so, preserve pituitary for its normal functions and to improve acromegaly symptoms. Various consensus statements have been published delineating the best criteria for disease management. Some of the strategies include surgery, pharmacological therapy and radiotherapy (Vasilev, Daly, Zacharieva & Beckers 2010).

The first-line treatment for acromegaly is transsphenoidal surgery for patients with microadenomas and benign macroadenomas. Surgery has been shown to normalize GH levels with approximated efficacy in 56-70% of appropriate patients. Tumor size and invasiveness are the major indicators for surgery outcomes. Well-circumscribed acromegaly patients show about 95% success whilst macroadenomas are controlled by 50 %( Melmed 2006).

Recent technology has developed technological advances. These technologies include endoscope-assisted microsurgery, three-dimensional navigation and intra-operative magnetic resonance imaging. However, more comparative studies on these techniques are insufficiently explored (Nomikos, Buchfelder & Fahlbusch 2005).

Drugs used to manage acromegaly include SRLs, GH receptor antagonists and dopamine agonists. Pharmaceutical therapy is only offered when surgery fails. It is often classified as a primary medical therapy. In the past, pharmacological therapy was prescribed to patients with contraindications or those unwilling to undergo surgery. A recent research has placed SRLs into the same position for surgery as the first-line therapy (Vasilev, Daly, Zacharieva & Beckers 2010).

Somatostatin receptor ligands (SRLs) work in a similar way to natural somatostatin. They bind to somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) on pituitary somatroph cells. This way, they suppress GH secretion. These drugs include Octreotide and Lanreotide. The drugs lower GH levels to less than 1microgram/liter in 57% of the patients and normalize IGF-I levels in approximately 67% of patients. SRLs also lower tumor size (Holdway & Rajasoorya 2004).

However, there are controversies over SRLs being used as pre-operative treatment. Carlsen et al investigation show 50% cure rate to patients treated with pre-operative octreotide in patients with macroadenomas in comparison to 23% non-treated patients. Currently, there are other molecules under clinical trials. These are pasireotide which analogs somatostatin but with a higher binding affinity to SSTR1 [2, 3&5]. Dopastatin is the second SRLs under investigation which acts on SSTR2 and on type2 dopamine receptor ligand (Bevan 2005).

Pegvisomant is a GH receptor antagonist. It acts by blocking GH effects on the periphery and in the serum IGF-I production. Currently, it is only offered when another treatment fails to normalize IGF-I. The drug’s efficiency in suppressing the IGF-I levels is up to 97%. However, the drug’s mechanism has raised a concern about tumor growth. The recent studies on this concern are re-assuring but regular examination of tumor mass should be done. Dopamine antagonist is used for the management of acromegaly for over three decades. However, the drug has low efficacy and its use as monotherapy is highly discouraged (Trainer et al. 2009).

Acromegaly treatment is incomplete without mentioning radiotherapy. It is often employed as a third or second-line treatment of tumor recurrent victims or those who portray intolerance to the pharmacological agents. The disadvantage with this method is that it is associated with hypopituitarism and holds a high risk of developing secondary brain tumors or worse still may cause mortality due to cerebrovascular disease (Castinetti et al. 2009).

Current implications

Significant achievements in acromegaly management have been realized in the past recent years improving the prognosis of the chronic disease. The combined pharmaceutical therapy has facilitated in managing disease control and even achieving a complete cure in a large proportion of acromegaly patients. The vast spectrum of clinical studies has unleashed lots of evidence on the efficacy of the present treatment strategies (Anat & Melmed 2008).

The primary preferred means of treating acromegaly is “transsphenoidal surgery by an experienced neurosurgeon” (Reid et al. 2009, p.208). Adjunctive medical therapy is only employed if the transsphenoidal surgery fails. SRLs are preferred for first-line medical therapy. Pegvisomant is also very efficient in biochemical control. However, its use is restricted by quite high prices. Despite the progress in management, acromegaly is still underdiagnosed and under-recognized. Therefore, physicians should take acromegaly diagnosis circumspectly (Reid et al. 2009).

Conclusion

Acromegaly is a serious condition that requires early diagnosis for a complete cure to the patients. Due to its sneaky onset, it is often either misdiagnosed or not be diagnosed early. If left untreated, Acromegaly results in severe complications and often premature death. It is a treatable condition for most patients especially when diagnosed early. Therefore, physicians should take acromegaly diagnosis circumspectly. Clinical guidelines are available delineating the best criteria for disease control. Strategies to aid the physicians to achieve effective treatment have been outlined carefully with surgery, pharmaceutical therapy and radiotherapy being employed to manage the disease.

References

Acomegaly 2011, The Symptoms of Acromegaly. Web.

Anat, B & Melmed, S 2008, ‘Acromegaly’, Endocrinology Metabolism & Clinical, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 101-22.

Antisense Therapeutics 2011, Summary Back ground and development update. Available from: <www.antisense.com.au>. [10 November 2011].

Bevan, J 2005, ‘Clinical Review: The antitumoral effects of somatostatin analog therapy in acromegaly’, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinolology & Metabolism, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 1856-63.

Cahynur et al. 2011, ‘Diagnosis and management of Acromegaly: Giant Invasive Adenoma,’ Acta Med Indones, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 122-128.

Castinetti et al. 2009, ‘Long term results of stereotactic radio surgery in secretory pituitary adenomas,’ Journal of clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 94, no. 9, pp. 3400-7.

Chanson et al. 2009, ‘French consensus on the management of acromegaly,’ Ann Endrocrinology, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 92-106.

Chason, P, Leselbaum, A, Blumberg, J & Schaison, G 2000, ‘Efficacy and Tolerability of the long acting somatostatin analog lanreotide in acromegaly; A 12-month multicenter study of 58 patients’, Pituitary, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 269-276.

Gordon, D n.d., Acromegaly. Web.

Holdaway, I, Rajasoorya, R & Gamble, G 2004, ‘Factors influencing mortality in acromegaly,’ The Journal of Clinical Endocrinolology & Metabolism, vol. 89, no. 2, pp. 667-74.

Holdway, I & Rajasoorya, C 1999, ‘Epidemiology of acromegaly,’ Pituitary, vol. 2, pp. 29-41.

Hurley, D & Ho, K 2004, ‘Pituitary disease in adults,’ The Medical journal of Australia, vol. 180, no. 8, pp. 419-425.

Levy, A 2004, ‘Pituitary disease: Presentation, diagnosis and management,’ Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and psychiatry, vol. 75, no. 1, pp. 47-52. d

Melmed et al. 2009, ‘Guidelines for acromegaly management an update,’ Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 1509-17.

Melmed, S 2006, ‘Medical progress: acromegaly,’ New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 355, no. 24, pp. 2558-2573.

Murray, RD & Melmed, S 2008, ‘A critical analysis of clinically available somatostatin analog formulations for therapy of acromegaly,’ Journal Clinical endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 8, 2975-2968.

National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Services 2006, Acromegaly. Web.

Nomikos, P, Buchfelder, M & Fahlbusch, R 2005, ‘The outcome of surgery in 668 patients with acromegaly using current criteria of biochemical cure,’ European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 152, no. 3, 379-87.

Nussey, S & Whitehead, S 2001, Chapter 7 The Pituitary gland. Web.

Reid et al. 2009, ‘Features at diagnosis of 324 patients with acromegaly did not change from 1981 to 2006; Acromegaly remains under recognized and under-diagnosed,’ Clinical Endocrinol (Oxf), vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 203-208.

Trainer et al. 2009, ‘A randomized, controlled multicentre trial comparing pegvisomant alone with combination therapy of pegvisomant and long acting octreotide in patients with acromegaly,’ Clinical Endocrinol (Oxf), vol. pp. 71, 549-557.

UCLA 2011, Conditions & Treatments. Web.

Vasilev, V, Daly, A, Zacharieva, S & Beckers, A 2010, ‘Management of acromegaly,’ Medicine Reports, vol. 2, no. 54 pp. 1-14.