The Ancient Middle East had produced many great civilizations, each with its own contributions to the region’s history and culture. Mesopotamia was one of the earliest centers of civilization in the Near East and the world in general, and its cities were among the most developed ones in terms of art and architecture. Yet none of the Mesopotamian urban centers came close to the glory and splendor of Babylon – the ancient and powerful city that had served as a capital to many empires throughout its history. One of the high points of the city’s development was the Neo-Babylonian kingdom that reached its peak in the late 7th – early 6th centuries BCE under the rule of Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II. The latter of these two undertook a massive renovation of the city, including the so-called processional way – the ritual passage from the Ishtar gate dedicated to Babylon’s goddess of love and war to the city’s center. Among other images decorating the passage, there were numerous panels depicting striding lions. Serving to promote the king’s legitimacy and Babylon’s splendor, the majestic beasts warded off evil and epitomized royal power.

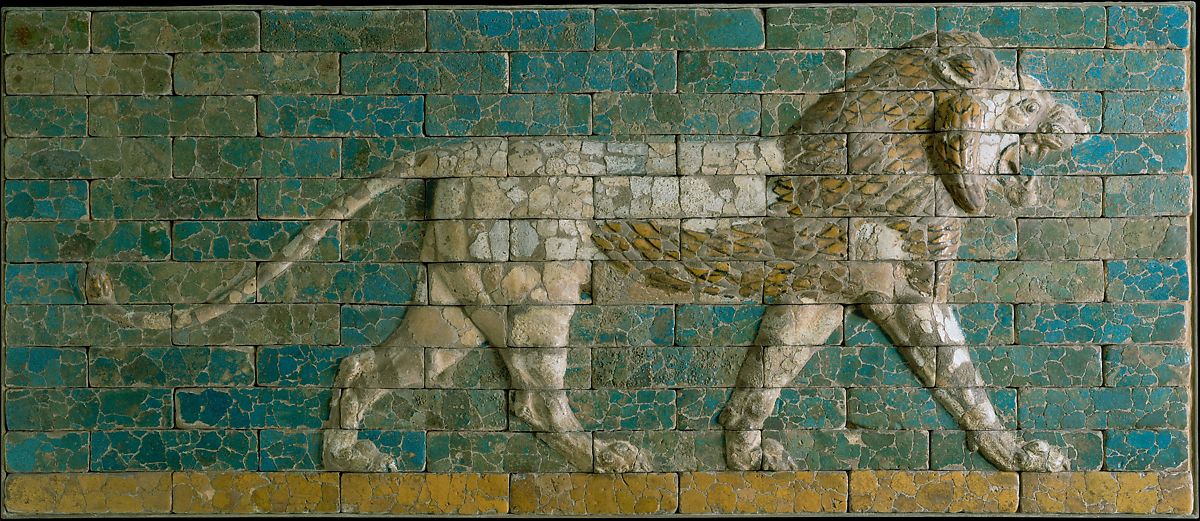

An example of the panel characteristic for Babylon’s Processional Way can be found in the Metropolitan Museum. The panel is 39 1/4 per 90 3/4 inches, and the titular lion occupies most of the pictorial space, meaning it is depicted close or lightly superior to its natural size (see fig. 1). Since Mesopotamia was not rich in stone, the panel is composed of glazed clay bricks. The background is in dark blue, while the lion itself is painted gold, inevitably catching the viewer’s eye due to sheer contrast (see fig. 1). The panel depicts the animal moving forward at a deliberate pace, providing a sense of self-assured might, and flashing its fangs as if warning a potential enemy (see fig. 1). The panel’s relief follows the contour of the lion’s body, flashing out the bones and muscles and adding to the impression of graceful feline power (see fig. 1). Thanks to this relief, the lighting also emphasizes the muscular curves of the striding predator (see fig. 1). Overall, the piece combines scale, color, relief, and light to provide an awe-inspiring image of a powerful beast.

To properly assess this piece of art, one needs to know the historical context that led to its creation. The panel was made during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BCE) as a part of the large-scale renovation of the Processional Way. When Nebuchadnezzar initiated his building projects, the Neo-Babylonian Empire was at the height of its power after its victories against Assyria, Judea, and Egypt. Correspondingly, rebuilding Babylon meant redefining the most powerful city of Mesopotamia to reflect the empire’s splendor. Nebuchadnezzar II reconstructed the Ishtar Gate, where the Processional Way began, and refurbished the entire passage with the aforementioned panels depicting striding lions. Essentially, Nebuchadnezzar II aimed to create a visual image that would fill any visitor with awe. The ancient authors, such as Herodotus, described Babylon’s architectural grandeur as having no rivals. Thus, the panel in question was meant to be not an ordinary artwork but a visible manifestation of Babylon’s glory at the high point of its political might and international renown. The striding lions were to become the symbol of the empire’s capital and one of its defining architectural features.

Naturally, in order to understand the meaning of the artwork for the audiences of its time, one needs to know more about what lions meant in Ancient Mesopotamian cultures. As the symbol of Ishtar, lions were a frequent occurrence in both Assyrian and Babylonian visual imagery. According to Babylonian belief, the lion imagery had the power to ward off evil and bad luck, guarding those around them. This is what Constance Gane means when noting that the lions on the panels, such as the one described above, had an “apotropaic function”. The way the panels framed the Processional Ways aligns perfectly with this assumption. The lions were depicted in continuous processions, as if not to leave any spot on the path unguarded. They were also oriented with their heads toward the city center and their tails toward the Ishtar Gate as if accompanying the ritual processions on both sides. Thus, the lions depicted on the glazed brick panels were not simply there for good looks but performed an essential spiritual function in the minds of Babylonians.

That is not to say that the lion imagery of the city’s Processional Way lacked purely pragmatic applications: apart from guarding the pilgrims against spiritual threats, it also endorsed the ruling monarch’s legitimacy. Aside from its presumed power of warding off evil, the lion in Mesopotamian culture had strong connotations with royal power. As noted by Krzystof Ulanowski, the Neo-Babylonia art consistently employed lions as a symbol of the monarch’s power. Yet the relation was not always symbolically straightforward: kings could assert their power not by associating themselves with felines but by defeating the fearsome beasts. The motive of the lion hunt that epitomized the monarch’s power over the mighty beast was a common one in Babylonian art.5With this in mind, it is feasible to assume that the glazed brick panels with striding lions framing the Processional Way affirmed Nebuchadnezzar II’s legitimacy in a similar way. The fact that the entire processions of lions warded off evils in Nebuchadnezzar’s capital could suggest that he possessed power over people and beasts alike. Considering this, the image of the lion served as a direct confirmation of the ruling monarch’s authority.

As one can see, the striding lion depicted on the Neo-Babylonian glazed brick panel from the 6th century BCE probably served the dual purpose of warding off perceived evils and confirming royal power. The piece uses the contrast between its blue and golden colors, realistic or even larger-than-life scale, and evocative relief to highlight the self-assured might of the large feline. Along with the numerous similar panels, it was created by the order of Nebuchadnezzar II to frame Babylon’s ceremonial Processional Way and impress everyone with the city’s architectural splendor. Apart from their purely visual beauty, lions had important spiritual meaning in Babylonian culture, as they were through to ward off evil and bad luck and, thus, guarded the passage through the city. Moreover, lions had strong and consistent connotations with royal power, especially since their positioning and function suggested that they guarded the Processional Way obeying Nebuchadnezzar II’s will. As a result, the impressive statue of the predatory cats guarding Babylon’s holy places served a twofold purpose of protecting the city from bad luck and affirming the awesome power of its rulers.

Bibliography

Gane, Constance E. “Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art.” PhD diss. University of California, 2012.

Lundbom, Jack P. “Builders of Ancient Babylon: Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II.” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 7, no. 2 (2017): 154-166.

Nielsen, John P. The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory, London: Routledge, 2018. Web.

Ulanowski, Krzystof. “The Metaphor of the Lion in Mesopotamian and Greek Civilization.” In Mesopotamia in the Ancient World: Impact, Continuities, Parallels, edited by Robert Rollinger and Erik van Dongen, 255-284. Münster: Ugarit Verlag, 2013.