A monopoly can take advantage of its market power by using price discrimination. In terms of this statement, list and discuss the various categories of price discrimination. For each category, substantiate your answer with the aid of examples.

A monopoly is a market situation in which a single company holds the majority of or the whole customer base of a certain item or service. Merchants in this type of market structure can set the price of products and services in the marketplace. Learning how they handle their pricing structure will help an individual understand their differential pricing. In a monopoly, unfair charges for offering various rates for much of the same commodity are evident (Long, 2018). Price discrimination is a marketing method in which a seller charges variable rates for the same service or product reliant on what they think the customer would agree to.

Varied marketplaces all over the world have different levels of price discrimination. First-degree value discernment is where a corporate charges each client the maximum they are ready to pay. This pricing varies from client to customer since the company charges the highest possible price for the customer to buy their items. As a result, the company can collect the entire consumer surplus and turn it into economic profit. This is a common pricing approach for companies with a lot of fixed costs. Clients who do not check their contracts, for example, are frequently charged greater fees by telecoms and energy companies. After a year or two, most businesses frequently raise the cost to a greater ‘variable interest rate.’ They only offer cheaper charges to more price-sensitive clients when they engage them.

All those who do not choose to call and enroll at a reduced fixed rate will wind up paying more. Those who are dissatisfied with their fees will call to negotiate a cheaper payment. As an outcome, the enterprise can charge a greater rate from those that are willing to pay while simultaneously gaining business from others who are looking for a lesser price. Because the cost of providing a service to an extra consumer is essentially non-existent, this functions well for businesses with significant fixed expenses. Whether the consumer chooses that business or another, the infrastructure and elevated expenditures will be paid. As a result, they are capable of extracting the most profit from each consumer by giving a lower price.

When a company engages in first-degree differential pricing, it consumes all of the excess generated by its customers. In a regular market, customers would pay a heavy price that is generally lower than what they would be prepared to pay otherwise. The consumer surplus is the gap between what they are prepared to pay and what they ultimately pay. Thus, there is no quantity demanded in price discrimination since each customer pays the greatest amount they are prepared to spend. This implies that the producer now owns the consumer excess, which is reflected in earnings.

Utility companies, for instance, frequently provide fixed-term contracts lasting a year or two, in which the client receives a cheaper rate. Consumers are switched to a greater variable interest rate after the contract ends. Nonetheless, a sizable portion of customers will continue on the variable interest rate, charging a huge monthly price. More price-conscious consumers will contact you and either transfer providers or switch to a lesser tariff. Customers that are less sensitive to prices, on the other hand, may stick with much the same utility supplier and variable rate, resulting in a higher bill for the same provision.

This link between customers and companies is depicted in the graph underneath. For instance, at $900, desire is zero, but it begins to rise as the quantity demanded signs of progress. It depicts the relationship of the overall market overall, rather than the relationship of a single client. As a result, at $800, demand begins to rise. This might indicate that 100 buyers are prepared to pay this amount, even though the cost of production for these is roughly $300, implying a $500 quantity supplied.

As the quantity demand curve goes down and approaches the equilibrium condition at $500, the price steadily rises, allowing for much more surpluses. It is worth noting that after this level, the cost buyers are prepared to pay lower than the cost of producing new things, and that is why the company ceases production. Millions and thousands of customers are buying at different price points between $900 and $500 across the market. The company produces a profit for each consumer, which is termed the total surplus. Based on how much they spend, it will differ from one consumer to the next.

Utility companies, for instance, frequently provide fixed-term contracts lasting a year or two, in which the client receives a cheaper rate. Consumers are switched to a greater variable interest rate after the contract ends. Nonetheless, a sizable portion of customers will continue on the variable interest rate, charging a huge monthly price. More price-conscious consumers will contact you and either transfer providers or switch to a lesser tariff. Customers that are less sensitive to prices, on the other hand, may stick with much the same utility supplier and variable rate, resulting in a higher bill for the same provision.

Second-degree price gouging, unlike all the other types of differential pricing, needs very little effort to separate clients. First-degree pricing discrimination, for example, necessitates the company to calculate each customer’s maximum willingness to spend. Third-degree pricing discrimination, on the other hand, necessitates the firm’s segmentation into categories such as age or wealth. Second-degree pricing discrimination, on the other hand, just needs the company to divide its customers between those who need to purchase in bulk and those who do not. Owing to the ease with which groups may be separated, it is possibly the most successful of all sorts of discrimination. Bulk discounting, on the other hand, motivates customers to spend so much. Offers like buy two, get one free, for example, push customers to buy additional so they can receive a third one for unrestricted. Even if they don’t necessarily desire another, the second and third appear to be significantly less expensive.

Because of economies of scale, businesses may engage in this form of pricing discrimination. Because operating margins for a single unit sold are typically relatively substantial, they can lower margins for future units to promote more consumption. While the second department’s gross margin may not have been as great as in the first, the net revenue is greater than if only one was sold. Many consumers, for example, obtain coupons in the mail or at the shop as a strategy to entice recurring customers to spend extra. The corporation can generate repeat business and improve sales by giving a discount to those customers. Vendors often use them, generally in assembly with a rewards card. Customers are tempted to come back to the corporate and buy more effects – though at a lower price – by issuing tokens.

For a variety of businesses, second-degree price gouging can be an effective pricing approach. It is mainly employed by businesses with strong profitability on the first unit of sales, which may then lower the price for future units to encourage more consumption. The pricing of ice cream bathtubs is seen in the graph below. The typical selling price for these tubs is $5. At this pricing, there is a market for 100 of them, bringing in $500 in income. However, if a bulk reduction is implemented and the cost is cut to $3.50, demand increases to 200, resulting in $700 in income (Roach, 2019). The company also has to build an additional 100 units, but because of scale economies, it can do so at a lower price than the first. This is owing to substantially lower costs, which arise as a result of warehouse merchants’ ability to deal with large orders. As a result, the firm’s overall earnings may be larger than those of comparable merchants.

Third-degree price fixing occurs when a company charges a different price depending on which customer category they belong to. Adults, the elderly, and youths pay varying costs at the movies, for example, while taxi drivers frequently pay a higher rate during rush hours. The most prevalent sort of differential pricing is third-degree differential pricing. Restaurants, movies, taxis, railway tickets, and merchants, among others, all utilize it. This is because it is quite simple to adopt and is far more successful than first and second-degree predatory pricing in terms of promoting customer loyalty. Charges are more closely related to the flexibility of expectations of the client – that is, prices are modified to the ability to pay the client.

Whereas first price discrimination optimizes income by obtaining the customer’s maximal willingness to spend, it is difficult to put into practice in the real world. As a result, it is more of an abstract notion that corporations strive for. Third-degree pricing discrimination is as near as most businesses can get to optimizing the desire to pay off their customers. The company must fulfill certain conditions to use third-degree pricing discrimination. First and foremost, the company must be able to recognize and split customers into several categories. Cinemas, for example, can recognize that the elderly and kids have different demand elasticity than adults and hence charge cheaper costs. Second, the company must be capable of preventing reselling. A senior consumer, for example, should not be allowed to purchase a low-cost ticket and then resell it to an adult. To go around it, businesses utilize ID regulations, which require customers to submit proof that they belong to a specific market category.

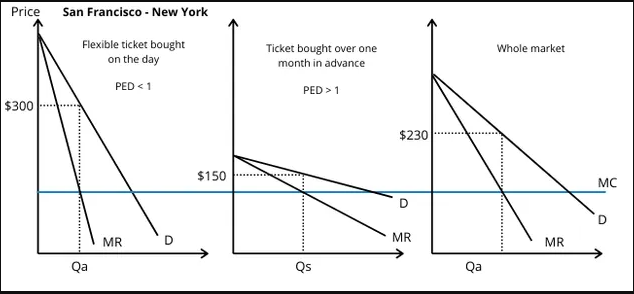

Third-degree price gouging entails dividing people into groups with differing explores effects. When it comes to plane tickets, for instance, some are highly sensitive to prices (flexible demand), and others are less price sensitive. When it comes to plane tickets, business travelers are more highly likely to be willing to pay extra. At the very same moment, they are the ones that frequently book last minute, allowing airlines to bill them a greater fare. Highly price-conscious people are more inclined to book well ahead of time to secure the best discounts. This is why so many flights give discounts to customers who book up or even a year ahead of time. The airline gains from greater cash flow, while the passenger benefits from a lower ticket price.

The division between both two groups is seen in the graph above. For starters, there are business clients that are capable of paying a higher ticket price. They have lower price sensitivity. As a result, the company will sell tickets until marginal income equals marginal cost. This is because the company is no longer profitable. Based on the demand curve of the business people, the ticket would cost $300 at this time. Profit is defined as the difference between it and the variable costs.

There are many more price-sensitive customers in the second scenario. This could also include, for instance, students. Their quantity demand is more flexible, which means they are more responsive to price fluctuations. As a result, the price hits $150 when marginal cost = marginal income. Anything below this represents profit for the company, but the operating margins for them are noticeably reduced. Finally, there’s the entire market, which would be a mix of business people’s price elasticity and learners’ elastic desire.

Some hotels, for example, provide discounts to clients who arrive at a specified hour. This may offer a less expensive ‘lunch-time’ selection or an ‘early-bird’ menu for consumers who visit during quasi-hours. This attracts more price-conscious clients while also boosting productivity in the company by allowing it to use its resources during certain busy hours. Veterans and healthcare professionals may be eligible for discounts at several establishments.

Reference List

Adachi, T. and Fabinger, M., 2017 ‘Output and welfare implications of oligopolistic third-degree price discrimination’, SSRN Electronic Journal, 35(3), pp.69-73.

Long, T., 2018 ‘Anti-Competitive Behaviour of State Monopolies from the Economics Approach concerning Vietnam’s State Monopolies’, Asian Journal of Law and Economics, 10(1), pp.31-73.

Michael Köhler, J., 2017 ‘A shift of nucleon mass could substitute the idea of an accelerated expansion’, International Journal of High Energy Physics, 4(2), pp.19-25.

Okada, T., 2019 ‘Third-degree price discrimination with fairness-concerned consumers’, The Manchester School, 82(6), pp.701-715.

Roach, T., 2019 ‘Market power and second-degree price discrimination in retail gasoline markets’, Energy Economics, 84(7)’, pp.104-514.

Yoo, S., 2021 ‘Spatial competition and price discrimination in theaters: The price dispersion of second- and third-degree price discrimination’, The Korean Journal of Industrial Organization, 29(3), pp.1-31.