Introduction

In today’s technology ridden world, computer crime and other related criminal activities are a booming business. Criminals, fraudsters, and even revolutionary terrorists seem to strike at every opportunity, leading either to financial losses, or loss in important data and information. In January of 2005, the United States federal government alerted people of a variety of scams that were being perpetuated through the internet, involving the solicitation of additional relief funds from unsuspecting victims affected by the tsunami hurricane disaster. This was typically discovered through the use of sophisticated digital forensics technology by the computer crime inter-agency, which was coordinated with the assistance of the various internet service providers within the country. By definition, computer forensics and digital forensics is described as the “preservation, recovery and analysis of information stored on computers or electronic media” (Ringhof, 2005). The technique often embraces all the factors about the surrounding technologies and digital evidence, paying significant respect to the legal aspects of whatever is collected, and is in most times viewed as a four step process that involves:

- Acquire: identifying and preserving data

- Analyze: carrying out technical analysis of the collected data

- Evaluate: Evaluating the legal aspects of the evidence collected

- Present: present the digital evidence as collected in a manner that is technologically and legally acceptable in a court of law.

Thus, though computer forensics is related to the digital recovery of information and data lost from within a computer, it presents a broader ideology which is mainly related to the investigation of criminal activities taking place through the use of computer technology. According to George Kessler (2005), computer forensics has seen the creation of various laws and regulations that have been imposed in order to check out the occurrence of crimes taking place through the use of computer technology, though they have been faced by the absence of evidence. Thus the maxim of the computer forensics scientist is not only to find the criminals carrying out the heinous activities, but also to find the evidence and present it in a manner that leads to the execution of legal actions against the culprits. According to Simon Racine (2007), the primary reasons for the rise in technological crimes are:

- Unauthorized use of computers without permission from the legal owners of the equipment through stealing of the username and password

- Accessing an unsuspecting user’s computer through the internet

- Releasing malicious software, either manually or through the internet, into an unsuspecting users’ computer

- Cyber bullying, stalking and harassment

- Email fraud

- Theft of information and data from a company through computer technology

Admissibility of Electronic Evidence

Disputed facts that have been collected during the course of an investigation can only be proven through the use of admissible evidence. According to Racine (2007), admissible evidence can be tentatively defined as that evidence which can, with enough proof be shown to hold sufficient facts that pertain to the case at hand, without calling on other questions as to why it has been submitted as evidence. However, if any part of the collected evidence is deemed irrelevant, then, this makes the entire evidence collected inadmissible. Electronic evidence is an important means of offering proof of issues that are otherwise un-resolvable by other trademark means in any court proceedings (Racine, 2007). This evidence is in most times relevant and probative with regards to its use, the strength of the mark, its priority, the manner in which it offers description, as well as the relevant class to which the consumer belongs. In the case study report of the FCC vs. Jack Brown, the Discovery Practices & Procedures Subcommittee of the Enforcement Committee carried out extensive research on the evidence and surrounding, creating a consistent and analytical report of the evidence collected. However, it is important to note that different courts and different judges/attorneys handle the cases and evidence submitted differently. The court in this case, for example, required authentication from the owners of the website, while others would have simply gotten the authentication from the Information Communication and Technology wings of the Cyber-Criminal Investigation department. Consequently, the subcommittee felt that the evidence that had been collected should be authenticated by any impartial observer with reasonable computing kills, averting to its veracity and accuracy. According to Racine (2007), a forensic scientist with the NYPD Crime Lab, the evidence that is collected by the team should be treated with the same level of examination and analysis as any of the conventional forms of evidence, promoting the predictability of the proceedings and thereby being beneficial to all parties involved (Galorath and Evans, 2006). All in all, the weight that is assigned to any piece of evidence that is forensically collected is to be determined by the court of law or legal tribunals, regardless of whether the evidence if electronic or not.

The authenticity of the materials that are collected by the forensic investigators is guaranteed by requiring that all the legal requirements are “satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the matter in question is what its proponent claims” (Berczuk and Appleton, 2003). However, the supporters of the case do not necessarily have to provide any legitimacy to the collected evidence; they only have to make a preliminary prima facie showing to the respective courtroom. Concerns might be heightened in cases where the data has already been processed rather than being simply stored. As a result of this clause, the extent of the initial showing and presentation is necessary in order to authenticate that the specific piece of evidence that has been offered depends on the nature of the evidence as well as its evidentiary purpose.

Best evidence rule

According to the best evidence rule, no par of the evidence collected in any investigation unless it is “the best that the nature of the case will allow” (Berczuk and Appleton, 2003). In this case, all computer generated evidence that has been copied off of an original print is deemed inadmissible. However, there are situations where the court can accept duplicated copies that can be explained by the fact that:

- The original copy has been lost

- Production of the original copy is impractical or burdensome

- The original evidence is in possession of another party

Furthermore, the best evidence rule can sometimes be used by some judges to reject the admissibility of copies; even they are correctly introduced in evidence. For example, if there exists a document that has been submitted into evidence and stays in storage for an enlonagetd period of time without being submitted to court, a judge can deem it inadmissible claiming that there is not wayu of knowing whether it has been tampered with while in storage (Kessler, 2005).

Acquisition Methods Used

The traditional method used by law enforcement officials during the collection and seizure of computers at a suspected crime scene is simply to unplug the computer and book it into the evidence log (Berczuk and Appleton, 2003). At this point, the forensic scientist requests that the computer be examined by a trained computer forensic examiner, who then makes a “forensically sound” copy of the hard drive contained in the computer, reviewing any evidence collected for contraband and suspicious content. On completion, the investigator writes a report of the findings, which are then presented at the court hearing.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) has issued a document that guides the forensic examination of digital evidence, stating that:

- Any of the actions taken by the forensic investigator to collect and secure digital evidence should not, at any one time, interfere with the integrity of that evidence

- The people conducting the forensic examination of seized digital evidence should be trained and well-qualified to do so

- Any activity relating to the seizure, examination and/or storage of digital evidence should have clear documentation that should be well preserved and made available for review

Data Recovery Notice

This is the process of salvaging whatever data or information is stored in a damaged, failed or corrupted secondary storage media that cannot be accessed through any other normal means (Berczuk and Appleton, 2003). Additionally, the recovery of this data may be required if there exists any logical or physical damages to the hard drives containing the incriminating data and which may keep the forensic examiner from easily accessing it through other ordinary means.

In the case of the FCC vs. Jack Brown, this will involve accessing the information that has been stored in different file formats. By removing the hard drives from the laptop with the Macintosh O/S and the desktop with the Windows operating system and mounting them onto other computer equipment running an operating system that is familiar to the user, the data from these two storage devices can be retrieved and collected as evidence. Additionally, the data from the thumb drive and the Blackberry cellular phone can be retrieved by directly connecting them to already running computers, sometimes necessitating the installation of additional software drivers to assist in accessing the devices. Furthermore, a crackdown on the Linux server that is believed to be hidden in the basement and mounting it on a computer running similar operating system renders any information that has been stored in the machine collectable.

If there have been files that have been deleted from the storage devices, references to them can be found in the directory structure on the hard drive (Bittner and Spence, 2007). By accessing this directory structure of the system volume information, the files can be restored.

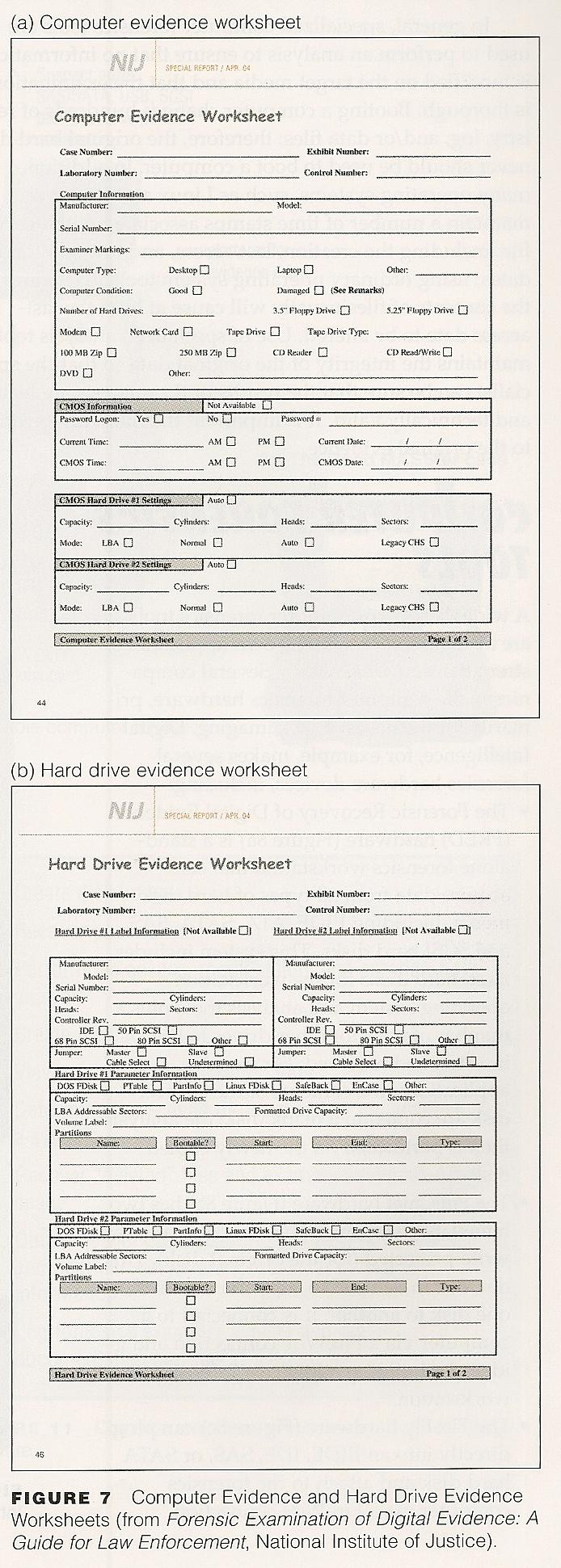

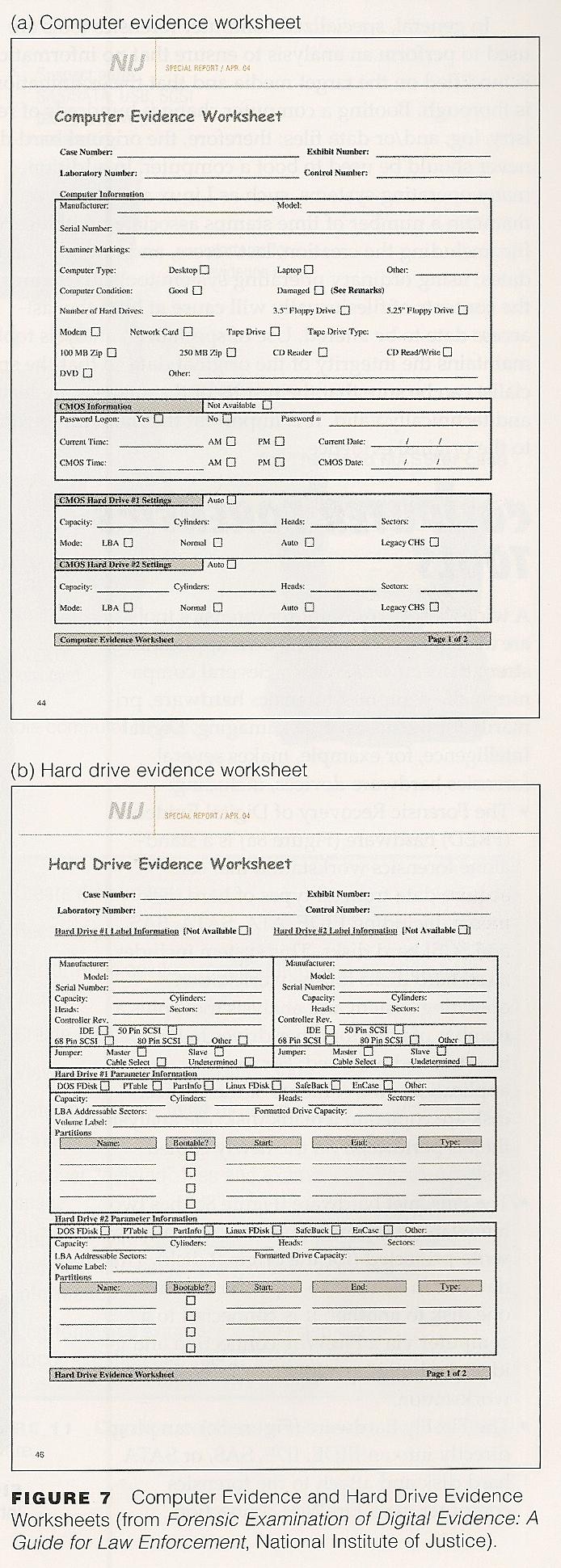

Evidence Form

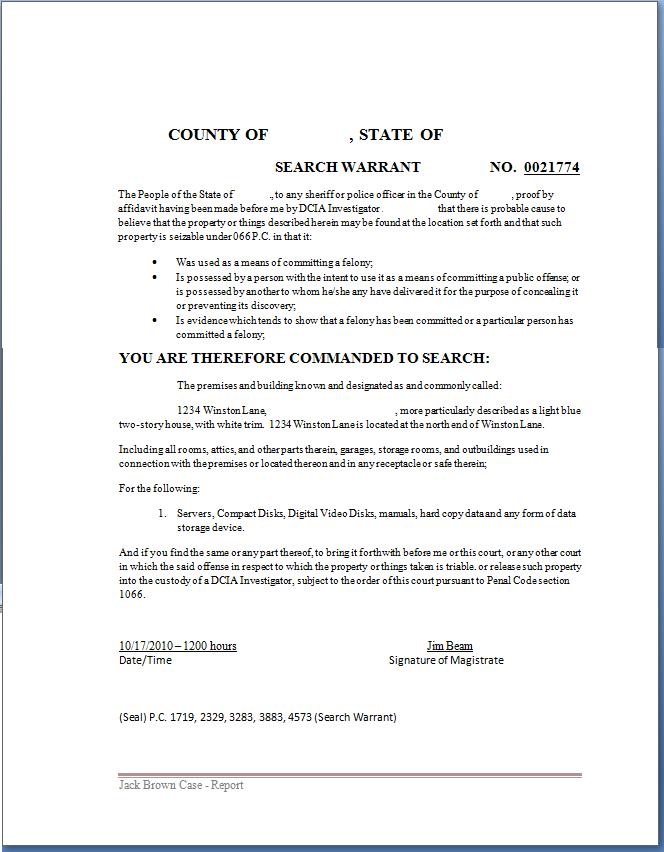

Sample Warrant

References

Berczuk, S.P., and Appleton, B. (2003). Recovering and examining computer forensic evidence. South Carolina, SC: USA Winthrop University.

Bittner, K., and Spence, I. (2007). Forensic Feature Extraction and Cross-Drive Analysis. London, UK: Rutledge.

Galorath, D.D., and Evans, M.W. (2006). Report on digital evidence. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin Publishing Company.

Kessler, G.C. (2005). The case for teaching network protocols to computer forensics examiners. New Jersey, NJ: Wizard Books.

Racine, S. (2007). Analysis of Internet Relay Chat Usage by DDoS Zombies. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin Publishing Co.

Ringhof, A. (2005). United States District Court District of New Jersey. Web.