Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my supervisor…………..for his encouragement and useful suggestions thought out my project.

I also wish to thank various construction industry professionals and insiders who graciously shared their experiences and opinions with me on this study.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge the support of my colleagues and family in our academic journey.

Abstract

Negotiation is gaining popularity as a means of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanism within the UAE’s construction industry. However, the method is not well understood within the industry. In this context, this study aimed at examining the prevalence of negotiation used in the UAE construction industry in contrast to other available dispute resolution mechanisms. The paper also examined the various obstacles in terms of legal implications or attitude issues about negotiation use in the UAE. Both primary and secondary data were used in this study. Secondary research was undertaken through an examination of various relevant literature on the subject from diverse sources. Such sources included books, journals, and credible websites among others. Primary research was undertaken using interviews and questionnaires. The study found that the level of awareness on the availability of negotiation as a dispute resolution mechanism stood at 80%. However, only a paltry 38% of the construction practitioners considered negotiation as the most ideal dispute resolution mechanism. Nevertheless, a relatively large percentage (92%) would consider using negotiation for solving simple and non-technical disputes.

Glossary

- ADCCAC Abu Dhabi Commercial Conciliation and Arbitration Centre.

- ADR Alternative Dispute Resolution.

- CPL Civil Procedure Law.

- CTL Commercial Transactions Law.

- DAB Dispute Adjudication Board.

- DCCI Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- DCCI Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- DIAC Dubai International Arbitration Centre.

- DIFC Dubai International Financial Centre.

- DIFC Dubai International Financial Centre.

- FIDIC Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils.

- FMCS Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service.

- GDP Gross Domestic Product.

- ICE Institute of Civil Engineering.

- JCT Joint Contract Tribunal.

- JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency.

- LCI Law Commission of Ireland.

- LCIA London Court of International Arbitration.

- NADRAC National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council.

- NEC New Engineering Contract.

- SFCCs Standard Forms Construction Contracts.

- UAE United Arab Emirates.

- UNCITL United Nations Commissions on International Trade Law.

- UNCITRAL United Nations Commission on International Trade.

- UNCTD United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Introduction

It is no doubt that the construction industry constitutes one of the largest sectors of any given economy. The critical contribution of the construction sector to the economies of various geographical entities can be measured through two variables. One of the variables is the contribution of the construction sector towards the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of various countries. The other variable is the contribution of the sector as an industrial employer (Malty & Dillon 2007). The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has a robust industry that competes favorably with the construction industries in different geographical entities. This is attested by the scope of the various construction projects undertaken in recent years. In this context, the UAE’s construction industry accounted for a fifth of the construction industry in the Arab world (RNCOS 2011: Gulf News 2011). It was also the second-largest contributor to the UAE’s GDP (Gulf News 2011).

The current study will look at negotiation as a dispute resolution mechanism in the context of the UAE construction industry. It is noted that conflicts a common feature in the construction industry. The aim is to look at how stakeholders make use of negotiations to resolve them. The use of negotiation will be compared to the use of other dispute resolution mechanisms such as litigation, arbitration among others. Data will be collected from clients, PCM consultants, contractors, consultants, and claim consultants in the industry. Questionnaires and phone interviews will be used to collect data.

Problem Statement

Despite the relatively positive outlook of the construction industry, disputes among various stakeholders have the potential to derail any economic gains made in the industry. The construction industry in the UAE has seen an increase in construction disputes (Mansoor 2010). The growing demand for lawyers versed with construction disputes attests to the increasing construction disputes within the UAE (Bin Shabib & Associate 2009). Construction disputes affect the industry in several negative ways. There is a loss of economic value through the engagement of lawyers in litigation processes and failure to complete the projects in the projected deadlines. This failure may result in the construction projects being completed at significantly higher costs than initially budgeted for. Construction disputes may also make given projects unprofitable which may make future investors reluctant to invest in the industry.

There are several causes of disputes within the UAE’s construction industry. These are classified into three broad categories. The three categories include economic factors, legal factors, and human factors. Economic factors as a cause of disputes within the construction industry can be analyzed within the context of the wider global economic crisis. The recent economic crisis resulted in cash strapped developers (Haddad 2009). The developers had limited cash liquidity to settle their debts from lenders and to pay their contractors, subcontractors, and employees resulting in disputes. Human factors can be understood from the three dimensions; disputes attributed to the contractor, disputes attributed to clients, and finally disputes attributed to the designer (Motsa 2006). These are construction disputes that can be directly associated with a given party’s failure to accomplish its part of the agreement. Such failure may be for example inadequate design drawings by the designer amongst other factors.

According to Motsa (2006), disputes attributed to the legal factors often occur due to inadequate understanding or compliance with set legal provisions. In agreement with Motsa, Haddad (2009) adds that disputes may also occur because of abuse of powers or provisions of the construction laws. Sometimes the disputes may occur due to loopholes inherent in the construction laws utilized. Negotiation is increasingly becoming a preferred mode of settling construction-related disputes in the UAE (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). Negotiation as a means of dispute resolution involves the disputing parties agreeing on an amicable solution to their problem. It often works best in instances where there is a provision of the same in the construction contract or where the conflicting parties mutually settle on the negotiation process. Some of the construction issues that can be negotiated include project completion dates, arbitration dates, and special work item compensation amongst other issues (Fleming 2003).

Rationale of the Study

There several reasons justifying the need for this research within the context of the UAE’s construction industry. In regards to dispute resolution methods, there are often limitations or obstacles that limit the utilization of a given dispute resolution method. These limitations may be in the form of construction industry players’ attitudes, lack of awareness of the process or procedures of the given method, and the inadequacy of the legal framework for the given method.

For example, Mansoor (2010) notes the inadequate legal framework for the negotiation dispute mechanism within the UAE. In this context, the UAE’s laws only implicitly provide for the negotiation method as a platform for dispute resolution within the UAE’s construction industry. These obstacles are not unique to the negotiation method but are generally applicable to many ADR methods. A deeper understanding of the negotiation method in terms of procedures, benefits, limitations, and legal framework will contribute towards increasing the body of knowledge on the method. This awareness is critical in expanding the available options for the disputing parties. The awareness will also guide the industry experts and players on any needed legal reforms towards strengthening the use of negotiation in the UAE’s construction industry (Motsa 2006).

While there are different dispute resolution methods for the disputing parties to pick from, each of the methods has its level of success within the UAE’s construction industry. These methods also have a diverse impact on the relationship of the various parties in the disputes. This paper seeks to find the level of the acceptance of negotiation as a means of dispute resolution mechanism in the UAE in comparison to other ADR methods. Mansoor (2010) has studied negotiation as a means of dispute resolution mechanism has often been studied within the context of the broader and more general ADR methods. In this context, several studies focus on the ADR methods and generally discuss negotiation from the sidelines. However, there is a shortage of studies exhaustively focusing on the negotiation as a means of dispute resolution mechanism within the UAE’s construction industry. This paper seeks to address this gap.

Aim of the research

The research aims to access the use of negotiation as a means of dispute resolution mechanism within the context of the UAE’s construction industry.

Objectives

- To find out the obstacles towards utilization of negotiation as the preferred mode of dispute resolution mechanism within the UAE’s construction industry.

- To access the prevalence of the negotiation dispute resolution method in comparison to other ADR methods in the UAE’s construction industry.

- To analyze the structure, form, and context in which negotiation is used within the UAE’s construction industry.

- To discuss the legal and institutional framework of negotiation within the UAE’s construction industry.

- To examine how the negotiation process and outcomes impact the relationship between various stakeholders within the UAE’s construction industry.

Research methodology

Desk work

The information for the research was obtained through primary and secondary sources. Secondary sources of information included credible websites, construction journals, construction electronic magazines, and various academic papers. The academic papers on the construction industry disputes were sourced from both local and foreign scholars. These secondary sources of information were critical in constructing the background information on the negotiation structure, methods, and types. The information was also critical in understanding the use of negotiation in the construction industry disputes from both the UAE’s and global context.

Fieldwork

Two primary sources of information were used that is interviews and questionnaires. These sources of information were critical in contextualizing the use of negotiation within the UAE’s construction industry, the prevalence of its use within the UAE, and the attitudes among the industry professionals on its relevance in modern times.

Hypothesis

Since of objectives is to study the obstacles that limit effective utilization of the negotiation method in dispute resolution the following hypothesis was formulated for testing.

“Negotiation method as a means of dispute resolution mechanism could be put to more use if there was adequate legal framework and if there was adequate awareness on its use”

Conclusion

The chapter has successfully set up the framework of the research as well as contextualized the dispute resolution mechanisms within the UAE. This chapter sets the platform for the ensuing chapters that discuss in detail dispute resolution mechanisms.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Introduction

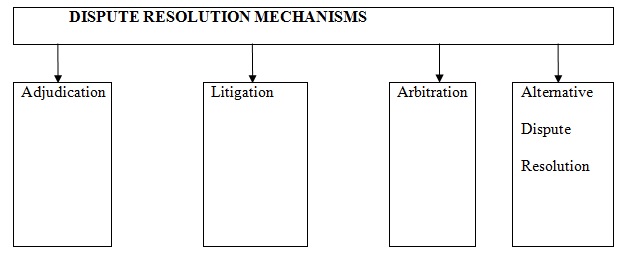

Dispute resolution methods used in the UAE’s construction industry include arbitration, adjudication, litigation, and ADR methods amongst others. The chapter discusses these methods within the context of the UAE’s construction industry.

Adjudication

According to Habib Al Mulla & Co (2011) adjudication is defined as a process that ‘…allows parties to resolve their disputes on an interim basis thus allowing work on the project to continue pending the outcome of litigation or arbitration proceedings’(p.1). Smith (2007) agrees with the inherent characteristics of adjudication as outlined by Habib Al Mulla & Co (2011). He notes that adjudication ‘…consists of an abbreviated court-like procedure under the direction of the Adjudicator, in which disclosure and/or rules of evidence may be applied flexibly or dispended with altogether’ (p.5).

Smith (2007) notes that the adjudication method saves on the cost involved in dispute resolution. Construction Week (2012) determines that this cost-saving is a result of the fact that work continues even as disputing parties look for a more permanent solution to their problem. However, Habib Al Mulla & Co (2011) notes that this method may be perceived to be technical and there can be infighting on the control of the process.

Habib Al Mulla & Co (2011) opines that the introduction of Dispute Adjudication Boards (DABs) in construction contracts is a major milestone towards the utilization of adjudication in the UAE’s construction industry. Hibbert (2012) emphasizes this point by stressing DABs are by default the first option in dispute resolution involving government projects in Abu Dhabi.

Litigation

The litigation method is a method that involves the use of courts to settle disputes (Kirchhoff et al. 2006). While decisions arrived through litigation method may be easy to enforce, the method is costly and time-consuming (Lew et al. 2003; Rau et al. 2006). Sanders (2004) further notes that the disputing parties also lose privacy about the content and form of their dispute. This is because litigation cases are often published in law journals for reference

Arbitration

There is a lack of consensus among scholars and institutional authorities on the definition of arbitration. Bridge Mediation LLC (2004) views arbitration as an ADR mechanism where the disputing parties present their disputes to a third person versed with the nature of their dispute who determines the outcome of the case. On the other hand, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTD] (2005) proposes a set of conditions that it claims constitutes arbitration and from which a definition can be implicitly derived. These conditions propose that arbitration is a private and consensual settlement of disputes in which it ‘leads to a final and binding determination of the rights and obligations of the parties’ (UNCTD 2005, p.5).

Mansoor (2010) opines there are several advantages of using the arbitration method in dispute resolution. There is flexibility in the choice of the arbitrator and this gives the disputing parties the psychological confidence of being in control of the process. Lew et al. (2003) and Rau et al. (2006) attribute this confidence to the acceptance of the arbitration outcomes by both parties in contrast to the litigation method. Kirchhoff et al. (2006) further cite privacy as another major advantage of the arbitration method.

Despite the advantages of arbitration, there are several disadvantages associated with the method. While arbitration may be perceived as cost-effective when compared with the litigation method, the same does not hold when compared with other ADR methods such as mediation and conciliation (Mansoor, 2010). In the same spirit, arbitration decisions and awards may take time to effect as compared to alternative ADR methods. The role of the third party has often been perceived as the greatest disadvantage of the method. In some contexts, one party may view the arbitrator’s decision as imposing and insensitive to its interests (Lew et al. 2003).In such a scenario, the arbitration decision and settlement may affect the business relationship between the two parties. The business relationship may be on future business prospects and the continuing or work in progress.

Dispute Resolution Boards

Some of the significant milestones within the UAE about dispute resolution mechanisms and arbitration, in general, include the adoption of the New York Convention in 2006 (Mansoor,2010). The New York Convention has two major functions. According to the New York Convention (2012), the convention applies to the ‘recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards and the referral by a court to arbitration’ (p.1). The adoption of the convention has boosted the UAE as a significant player in the international economy. This is based on the notion that international contractors feel safe as they are covered by the convention in case of disputes. In this context, the convention obliges the contracting state (in this case UAE) ‘to recognise such awards (foreign arbitral awards) as binding and to enforce them in accordance with their rules of procedures…’ (New York Convention 2012, p.1). In this context, the recipient of a foreign arbitral award needs only to provide the arbitral award as well as the agreement supporting the same to the courts for enforcement (New York Convention 2012, p.1).

Since these early milestones, the UAE has grown through the establishment of Abu Dhabi Commercial Conciliation and Arbitration Centre (ADCCAC) in Abu Dhabi by the Abu Dhabi Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Dubai International Arbitration Centre (DIAC), Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and Dubai International Financial Centre – London Court of International Arbitration (DIFC- LCIA) (Mansoor 2010; Rau et al. 2006).

Conclusion

The establishment of the arbitration centers goes a long way in availing arbitration services in the UAE. This is expected to expand the dispute resolution options in the UAE’S construction industry. Such an expansion would be critical in making the UAE’s construction industry to be more competitive.

Negotiation

Introduction

Scholars from diverse backgrounds have advanced several definitions of negotiations. Gulliver as cited in Moor & Weigand (2004, p.4) defines negotiation as

‘…a process in the public domain in which two parties, with supporters of various kinds, attempt to reach a joint decision on issues under dispute’. On the other hand, Robinson & Volkov (1998) defined negotiation as ‘…a process in which the participants bring their goals on the bargaining table, strategically share information , and search for alternatives that are mutually beneficial ‘ (p. 1). In the context of dispute resolution, the ultimate aim of negotiations is to reach ‘…a joint decision on issues under dispute’ or ‘…a joint decision on their common concerns’ or ‘…a mutually acceptable agreement’. Reaching a consensus on the way forward is thus a critical component of a successful negotiation process. The need to arrive at these joint decisions or agreements is based on the notion that negotiations involve two or more participants. These participants have their viewpoints or interests.

Prerequisites for negotiations as a dispute resolution mechanism

In a view supported by World Bank (2006), Robinson & Volkov (2004) opine that there are several conditions, behavioral and legal requirements necessary for effective negotiations to take place. In the context of the UAE’s construction industry, for the disputing parties to use the negotiation method there must be provisions for it in the dispute resolution clauses (Mansoor 2010). Moor & Weigand (2004) cites several such conditions e.g. the willingness of the disputing parties to negotiate, and the demonstration of good faith towards each other. The availability of several viable options to a dispute resolution is another major component that makes negotiation a viable means of dispute resolution. In the absence of viable options to a dispute, there would be no incentive to the disputing parties to enter into a negotiation process.

Negotiation approaches; Integrative versus distributive approaches

Integrative negotiation seeks to benefit each of the disputing parties in a win-win scenario (Moor & Weigand 2004). The essence of integrative negotiation is for each of the parties to walk away with something. On the other hand, the distributive negotiation process assumes a finite number of solutions to a dispute or limited gains to be made from dispute resolution (World Bank 2006). The essence of distributive negotiation strategy is to try to maximize one’s gain from limited resources or fixed pie.

The use of negotiations in the UAE’s construction industry: A review of past studies

Negotiation as a means of dispute resolution in the UAE’s construction industry has been discussed within the wider context of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods. The ADR methods include negotiation, mediation, and adjudication (Al-Tamimi & Company 2011). Mansoor (2010) notes that in the recent past ADR methods are favorably competing with traditional dispute resolution mechanisms as the preferred mode of dispute resolution mechanism. It is now a current practice to make provisions for dispute resolution clauses in construction contracts. In terms of an order of hierarchy, such contracts provide for negotiation as the starting point in dispute resolution (Motsa 2006). There are also provisions for mediation, adjudication, arbitration and litigation should negotiation fail.

In the recent past, negotiation has become popular as a means of dispute resolution mechanism in the UAE’s construction industry. In this context, negotiation is often used as the primary mechanism of construction industry disputes within the context of the UAE’s construction industry (Al-Tamimi & Company 2011; Motsa 2006). This is because of the several advantages associated with the method.

There are several advantages associated with the use of negotiation as a means of dispute resolution in comparison with the other methods. Negotiation saves on time that would have otherwise been used in the lengthy litigation process (Mansoor 2010; Al-Tamimi & Company 2011). It is also not a costly method as the disputing parties often negotiate without the involvement of paid third parties. World Bank (2006) cites that the integrative negotiation maintains the business relationship between the disputing parties. The integrative negotiation process also encourages examination of causes of disputes in-depth and thus establishes long-term solutions that may forestall a reoccurrence of the same problem. Overall, the negotiation method is an efficient way of resolving conflict-related disputes.

Disputing parties often use the negotiation method to strike a balance between completing the construction works and resolving the conflict (World Bank 2006; Moor & Weigand 2004). In this context, there is a mutual aim of completing the work with minimal delays and costs. However, in contexts where there are little trust and goodwill among disputing parties the negotiation process is likely to fail. In the context of the construction industry, negotiation is often a voluntary pre-hearing session or a mandatory pre-trial session among the disputing parties (Mansoor 2010).In this sense, negotiation may precede other forms of dispute resolution mechanism. Motsa (2006) notes negotiations in the pre-trial stage may proceed under the direction of a judge. At this stage, the disputing parties may appoint attorneys or representatives to negotiate on their behalf. These representatives must consult the disputing parties before agreeing.

Several factors determine the outcome of the negotiations in the UAE’s construction industry. Despite the negotiation being an ideal way of avoiding trial, the expertise and the attitudes of the attorneys or representatives may influence the outcome of the negotiations (Mansoor, 2010).In agreement with Mansoor, Motsa (2006) states that the negotiation strategies adopted which are integrative versus distributive negotiation strategies also determines the success of the negotiations. The success of the negotiation method is often achieved when any decision to initiate any dispute resolution process is arrived at as a rational and imperative inference (Al-Tamimi & Company 2011). Such an inference can only be achieved through a thorough and principled negotiation process. In this context, negotiation is not approached from a hostile perspective.

Within the construction industry in UAE, mediation is often used in contexts where negotiations fail. World Bank (2006) cites that mediation is a method closely related to the negotiation method and falls within the ADR framework of dispute resolution mechanism. However, mediation involves the use of a third-party mediator to resolve the dispute between the parties (Motsa 2006). The disputing parties often jointly appoint the mediator. In this context, the mediator is expected to be a neutral person. The mediator thus often works as a facilitator to the dispute resolution process (Mansoor 2010). While mediation has similar benefits to the negotiation method, it can be especially useful in solving disputes with advanced technical and legal issues. Despite the advantages of utilizing the negotiation method in the UAE’s construction disputes, there are several shortcomings associated with the method. The method may prove inadequate in the interpretation of controversial and complex issues. In this context, a legal authority such as a court or arbitral tribunal may facilitate negotiations.

Institutional and Legal framework for negotiating in the UAE’s construction industry

In the context of construction, there are two broad types of construction contracts: bespoke construction contracts and the Standard Forms Construction Contracts (SFCCs) (Shnookal & Charret, 2010). Bespoke construction contracts are construction contracts drafted primarily to focus on the project at hand. These kinds of contracts can be tedious and costly to draft (Kerur, 2011). This is based on the need for legal expertise to factor all the project specifics in the contract. On the other hand, the bespoke contracts offer a more suited draft of legal provisions specific to the project at hand.

The second type of construction contract is the Standard Forms Construction Contracts (SFCCs). Various professional bodies have developed these generic construction contracts over time. There are several SFCCs used in the construction industry include Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC), New Engineering Contract (NEC), and the Institute of Civil Engineering (ICE) contracts (Shnookal & Charret, 2010; Mansoor 2010). Other standard forms of contracts include Joint Contract Tribunal (JCT) contract amongst others. The UAE’s construction industry uses the FIDIC SFCC as well as appropriate local UAE federal laws. In a global context, the NEC published by the United Kingdom’s Institute of Civil Engineers is the next major competitor to the FIDIC laws (Motsa 2006).

There are several advantages associated with the SFCC in comparison to the bespoke contracts. One of the major advantages of the SFCCs is the element of certainty in the execution of the contract (Kerur 2011; Mansoor 2010). The legal provisions in the SFCCs have been tried and tested in litigation in various legal jurisdictions. In this context, the parties can have some insights into how various clauses have been interpreted in a litigation environment (Motsa 2006). This gives the parties a sense of meaning and intent of the various clauses in the SFCC.

In contexts where the SFCC is not heavily amended to suit the project into consideration, the legal clauses are easy to adapt quickly and flexibly. This saves the time and costs involved in the procurement of the legal provisions to adapt to the given project (Kerur 2011; Shnookal & Charret, 2010). It is also far much easier and cheaper to amend SFCC to suit the project as opposed to constructing a fresh bespoke contract. SFCCs generally have a wide scope on issues that may arise in the construction work (Moor & Weigand 2004)). In this context, parties do not necessarily have to think about all the legal provisions that they need in their contracts.

Despite the advantages associated with the SFCCs, they also have several disadvantages associated with its use. Complex projects may require contracts that address the unique risks involved in the construction project. In such contexts, the generic SFCCs may not be adequate to cater and provide for the risks involved (Shnookal & Charret 2010). On the other hand, inadequately amended SFCC may pose an even greater risk should a dispute arise. This often occurs in scenarios where clauses are amended and the related clauses are not appropriately amended. In this context, it is critical to ensure that whenever amendments are carried out then other related clauses must be also appropriately amended. This prevents a scenario wherein in case of a dispute there is a lack of consistency in the intent and the meaning of the various clauses (Kerur 2011).

In the context of the UAE’s construction industry legal framework, we will address the framework from two dimensions: Fédération Internationale des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC) legal provisions and the UAE federal laws (Kerur 2011). It is important to note that the construction laws can only be studied from a holistic perspective as opposed to laws that specifically support negotiation as a means of dispute resolution in the UAE’s construction industry (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). This perspective is based on the provisions of FIDIC contracts that form the backbone of the UAE’s construction laws. According to Mansoor (2010), FIDIC contracts put provisions for dispute resolution mechanisms. However, the contracts contain ‘…undefined amicable settlement process…’ before the parties initiate adjudication and litigation (Mansoor 2010, p.21). This means that FIDIC contracts in the context of the UAE’s construction industry contain provisions for the undefined process of harmonious settlement and arbitration clauses. There is therefore provided for ADR means of dispute resolution implicitly in the FIDIC type of contracts.

The general implication of these FIDIC provisions is that arbitration or litigation process will only start when attempts at cordial settlements fail. Therefore, the undefined amicable dispute settlement processes in the FIDIC contracts have a significant influence on the contemporary dispute resolution practices (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). This entails dispute resolution through the informal settlement discourses (Mansoor 2010). Therefore, negotiation as a mechanism of dispute resolution is founded on the efforts towards amicable settlement of differences. It is now mandatory for all the parties to comply with Federal law No.4 of 2001 before filing an action in a federal court. This obligation is only exceptional in Dubai and Ras Al Khaimah.

The federal law No.4 of 2001 was passed on the 3rd of January 2001. It provides for the appointment of one or more reconciliation committees of the first instance by the ministry of justice. A judge presides over the committees that constitute two members of the judicial authority. The main objective of these committees is to encourage and facilitate the amicable settlement of commercial and civil disputes of whatever value (Mansoor 2010). Nonetheless, any party has an entitlement of applying for a letter of no-objection from the relevant reconciliation committee if they so wish not to resolve their dispute in an amicable manner (Al Tamimi & Company 2011).On the other hand, the UAE’s Civil Procedure Law does not expressly recognize Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods such as negotiations, mediations, and conciliation. The UAE’s Civil Procedure Law only provides for arbitration and litigation methods. In this context, it is sometimes difficult to enforce agreements arising from the ADR methods.

FIDIC construction contract provisions as used in the UAE’s construction industry

The International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) standard is a major legal framework used in the UAE’s construction industry (Mansoor 2010). FIDIC is a French acronym for the Federation of consulting engineers that is Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC 2011). FIDIC contracts are the most commonly used standard construction contracts worldwide (Shnookal & Charret 2010). In a global context, FIDIC laws are widely used by development agencies such as the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) amongst others. In this context, the FIDIC laws are published in thirteen languages for global usage.

The central pillar of FIDIC laws is the engineer’s role. In the FIDIC standard form of contract, the engineer plays a supervisory role otherwise performed by the architect in other standard forms of contracts. In this context, the engineer is a central figure in the certification of progress and quality of the construction work. However, some scholars have argued that the role of an engineer in the FIDIC standard form of contract is perhaps its greatest weakness (Shnookal & Charret 2010). Perhaps the central role of the engineer is can best be understood from the historical context in which the FIDIC laws conceptualized. First published in 1957 under the title’…Conditions of Contract (International) for Works of Civil Engineering Construction…’ (FIDIC 2011). In this context, the laws were primarily designed for civil engineers in construction works where an independent engineer had designed the work on the employer’s behalf (Mansoor 2010).

According to FIDIC (2011), there are four basic contracts covered by the FIDIC legal framework. These contracts include the red book, the yellow book, the silver book, and the Green Book. The scope of the red book includes the legal conditions for both engineering and construction works (Mansoor 2010). It is worth noting that the employer designs these works. While there are several versions of the red book such as 1973, 1977, and the 1992 editions, the 1987 and 1999 editions are the most commonly used in the UAE’s construction industry (Kerur 2011).

Kerur (2011) notes that the 1987 red book is considered employer-friendly and as such is widely used in private construction work. On the other hand, the construction contracts between the government and the private sector are generally covered by the 1999 version of the red book (Mansoor 2010). This was a result of Abu Dhabi’s government decision in 2008 to adopt this version (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). This decision was contained in the new contract titled ‘The 2007 Abu Dhabi Government Conditions of Contracts’ (Bin Shabib & Associates 2009, p.2). This new contract contains derivatives of the 1999 version of the red book. Law number 21 of 2006 and the executive decision number 1 of 2007 brought these laws into force. However, the limited use of the edition by the private sector has hampered its use and acceptance in the construction industry.

The introduction of the modified version of the 1999 FIDIC laws was because of several shortcomings of the 1987 FIDIC laws. In this context, the 1999 FIDIC laws contained provisions for dispute adjudication boards and diluted some engineer’s powers (Mansoor 2010). These laws contain clauses allowing the contractor to make claims in the event of an escalation of the price. Also, there are several amendments about variations and design amongst other aspects. However, there are several disadvantages to the modified 1999 FIDIC laws. The most notable is the erosion of the checks and balances that attempted to distribute the risks in an even manner between the contractor and the employer (Bin Shabib & Associates 2009).

Dispute resolution mechanism in the context of FIDIC laws

In the context of dispute resolution, the 1987 and 1999 FIDIC construction contracts have several points of convergence and divergence. Under the 1999 FIDIC laws, the disputes are primarily resolved by the Dispute Adjudication Board (DAB) as a neutral decision-maker (FIDIC 2011). This contrasts sharply with the 1987 FIDIC laws where the engineer who is hired and paid by the employer undertakes the decision-making role. In the latter form, the engineer is expected to portray impartiality. However, this expectation has generally aroused criticism based on the background that the engineer is paid by the employer and thus has a high probability of being biased (FIDIC 2011; Motsa 2006). This reality has made many participants in the construction process, especially contractors not consider the engineer as a neutral decision-maker. Lee as cited in Mansoor (2010) argues that the engineer’s neutrality can only be resolved when the engineer is under the joint selection and payment of the contractor and the employer.

Mansoor (2010) opines that there are significant changes in the 1999 FIDIC laws about the engineer’s role. The 1999 FIDIC laws assume that the engineer acts for the employer. This contrasts the role of the engineer in the 1987 FIDIC in which the engineer is not considered friendly or impartial (FIDIC 2011; Motsa 2006). However, 1999 FIDIC laws impose conditions on the engineer who is under contractual obligation to exercise fair determination. Therefore, Al Tamimi & Company (2011) infers that the 1999 FIDIC laws bestow dispute resolution mechanism with more clarity than the 1987 FIDIC laws.

In the procedural set-up of claims and disputes under the 1987 FIDIC laws, clause 67 stipulates that the process of dispute resolution commences with the referral of the dispute to the engineer (Motsa 2006; Mansoor 2010). This can overflow to arbitration, whose failure can result in litigation. However, this legal framework provides room for an amicable dispute resolution mechanism. This is the provision that gives room for ADR providing alternatives to arbitration and litigation process under the 1987 FIDIC laws (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). However, failure of negotiation and other amicable dispute resolution methods often result in arbitration as the end resort. Further to Mansoor’s observations, Bin Shabib & Associate (2009) state that the 2007’s Abu Dhabi Government Condition of Contracts contains arbitration clauses if the appointed dispute adjudication board (DAB) cannot resolve the dispute. This evidences the open willingness to arbitrate by the UAE’s government agencies.

Two major differences are evident from the utility of 1987 FIDIC laws or 1999 FIDIC laws in dispute resolution. Firstly, there is the issue of impartiality. Seppala as cited in Mansoor (2010) determines that the decisions that will emanate from the DAB have a higher likelihood of fairness and neutrality as compared to those deliberated by the engineer by clause 67 of the 1987 FIDIC laws (Motsa 2006). This is due to several factors. In most cases, the DAB will be constituted of lawyers and construction professionals who will often portray independence since both parties select them. Moreover, the deliberations of the DAB are likely to provide a lot of assistance in court if the parties choose to proceed with arbitration as opposed to the engineer’s decisions. This is founded on sub-clause 20.6 of the 1999 FIDIC laws that stipulate that ‘…any decision of the DAB shall be admissible in evidence in the arbitration’ (FIDIC 2011, p.1).

There is also no provision in the 1999 FIDIC laws that the DAB will be called upon to provide evidence in the arbitration process. This is because they do not possess any authentic firsthand knowledge of the work under dispute. This is based on the background that their role is primarily that of deciding on disputes presented to them (Mansoor 2010). However, 1987 FIDIC laws provide that the engineer may be called upon to give proof before the arbitrators in an arbitration proceeding.

Construction laws in the context of the UAE’s Federal and Local laws

The legal and institutional framework for negotiating in the UAE construction industries is also contained in several parts of the UAE’s federal laws. The UAE is a civil law country whose primary source of law is statutory code. Thus, the foundation of law in the UAE is the Civil Code whose provisions are applicable in instances where there is no specific legislation to the contrary and where specific legislation is silent on a specific issue (Brendel, Barrette & El-Riachi 2010). The civic code must be reviewed to the UAE Federal Law No. 18 of 1993. This federal law issues the Commercial Transactions Code of the UAE, as amended, which encompasses specific contracts that meet the condition of a commercial contract (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). In the context of court procedures, the UAE courts are under the governance of the UAE Federal Law No. 11 of 1992, which issues the Code of Civil Procedure of the UAE as amended (the Civil Procedure Code).

In the context of the UAE’s construction laws, there are several relevant portions of the UAE federal laws. These laws include the UAE’s federal laws number 2 of 1987, number 11 of 1992, number 18 of 1993, and number 6 of 1997(Al Tamimi & Company 2011). The UAE’s federal law number 11 of 1992 contains UAE’s Civil Procedure Law (CPL) (Brendel et al. 2010).On the other hand, the UAE’s federal law number 18 of 1993 contains the Commercial Transactions Law (CTL). The number 2 law of 1987 contains the UAE’s Civil Code. The CPL and in particular articles 203 to 219 set the arbitration laws framework (Al Tamimi & Company 2011). On the other hand, articles 6 and 11 of the federal law 18 of 1993 (CTL) examines the construction contracts within the context of commercial contracts. In this sense, the construction contract must meet the requirements of a commercial contract as outlined in UAE’s federal laws. Federal law number 6 of 1997 covers contracts between the government and the contractors in Dubai.

Several stringent mechanisms have been formulated in the UAE to enhance the dispute resolution process. In the context of negotiation as a mode of dispute resolution, Motsa (2006) opines that settlement is achieved through the agreement of the parties. However, although this method can be effective and efficient in averting trial, its success is solely dependent on the attitude and expertise of the representatives. In a situation where the involved individuals are opposing attorneys, they ought to be dedicated towards the successful accomplishment of their mission, failure to which they might as well be in court (Mansoor 2010)

Mansoor (2010) cites the recent introduction of the DIFC-LCIA arbitration center as a major step undertaken in the UAE’s construction industry. This center is governed by its mediation and arbitration rules. The center is governed by the DIFC arbitration rules that are founded on the United Nations Commission on International Trade (UNCITRAL) Model Law. One of the imperative steps towards avoiding the courts by this center is that DIFC courts encourage the parties in dispute to consider alternative channels of seeking justice such as conciliation and mediation in their process of dispute resolution. However, unlike the ADR law (Centre of amicable settlement), the DIFC court does not make it mandatory for parties to engage in justice through reconciliation before litigation (Motsa 2006). This is based on the background of Law number 16 of 2009 (the ADR Law) where Dubai formed a center of amicable settlement of both civil and commercial disputes in the area under its jurisdiction aimed at resolving the disputes during their early stages. In this context, any dispute that falls within the provisions of law number 16 of 2009 must first be tried by the center for amicable settlement (Brendel et al. 2010).

Mansoor (2010) discovered that in a move aimed at encouraging parties to reach dispute settlements in early stages, the center has put forth a mechanism whereby half of the registration fee that is payable for registration is refunded to the parties upon reaching a settlement. This is to act as an incentive in encouraging other parties to follow similar steps in resolving their disputes. The formation of ADR Law can thus be perceived as an act of good faith by the Dubai government geared towards encouraging and enhancing the utility of negotiation amongst other ADR methods in dispute resolution without ending in courts or arbitration proceedings in the UAE and specifically in Dubai (Brendel et al. 2010). ).

There has been a negative perception of the mandatory engagement of the ADR process before proceeding to the courts (Motsa 2006). However, there is some optimism as this process limits the number of disputes ending in the courts. Consequently, the amount of time and costs involved in dispute resolutions among the involved parties is minimized. Besides, players in the construction industry in the UAE still have a certain degree of uncertainty concerning the applicability of the ADR law. This is because its utility is excluded from certain types of cases. This includes cases where there is the involvement of the government as well as in the disputes that are under the jurisdiction of the DIFC courts (Mansoor 2010).

Nonetheless, despite adjudication being an effective and paramount mechanism in resolving disputes in the UAE, Mansoor (2010) notes that this recent development is yet to be fully embraced. This can be attributed to the fact that in regions like Abu Dhabi, there is still limited knowledge and familiarity concerning the 1999 FIDIC laws amongst the construction participants. This is due to its low utilization in the private sector. Al Tamimi & Company (2011) attributes this phenomenon to the lack of a statutory force that will be integral as the enforcement of adjudication award. Consequently, this deficiency continues to curtail the success of adjudication. As a result, there is a projected ineffectiveness of adjudication in the UAE as long as it does not have the much-needed statutory support.

However, some optimists like Taylor as cited in Mansoor (2010) infer that the sole adoption of 1999 FIDIC laws by the government of Abu Dhabi is an imperative step towards enforcing the ADR practice in the UAE. Therefore, the early involvement of the adjudication board in dispute resolution limits the development of potential disputes (Motsa 2006)

About the economic advancement, there is a widespread feeling that if the process of adjudication is made effective, there is bound to be an improvement in terms of the cash flow in the industry. This is because the most predominant dispute resolution mechanism in the UAE, mainly arbitration and litigation, is perceived as slow and prohibitively expensive (Motsa 2006). This is concurrent with the view by the Dubai Chamber of Commerce and industry that the practice of ADR in the UAE will be fundamental in supporting business growth and positive results (Mansoor 2010). This is combined with the disadvantage of the arbitration and litigation processes being disfavoured since they strain the working relationships between the employers and the contractors in the construction industry. Therefore, ADR methods like negotiation can be ideal in dispute resolution mechanisms, mostly if they enjoy the backing of high levels of technical and legal knowledge.

Mansoor (2010) infers that the effective use of ADR methods like negotiation in dispute resolution in the UAE is paramount to the much-needed development in the construction industry. This is because their utility will ensure that both parties in the dispute will be in a position to concentrate on the projects and thus meet their goals. Some of these goals are to finish the projects within the required timeframe and budget while meeting the required quality (Motsa 2006).

As Motsa (2006) suggests, it is necessary to manage disputes to improve production in the industry without major delays and cost overruns. However, there is often a dilemma on whether to commence a dispute resolution process, either arbitration or litigation before the completion of the work at hand. Al Tamimi (2011) cites several reasons concerning this quandary. Firstly, the dispute resolution process may affect the progress of works. This is because quality work progress is dependent upon a good relationship between the employer and the contractor. In this regard, the offended party may be reluctant to commence dispute resolution processes in fear of denting the most imperative relationship with the employer (Mansoor 2010)

Also, commencing the dispute resolution process is not a guarantee that the dispute will be successfully resolved to the satisfaction of both parties. If the latter objective is not achieved, it can result in strained relationships to the extent that termination of the contract may be projected shortly (Mansoor 2010; Motsa 2006).

Moreover, substantial damaging of the relationship between the employer and the contractor which can emanate from the commencement of arbitration or litigation before the work completion and without principled negotiation and principled negotiations will adversely affect the cash flow into the project at hand (Motsa 2006). This is based on the fact that more monies will be used in pursuit of the claims rather than being recovered through the work in progress (Mansoor 2010).

The second predicament is that the quantification of claims may be difficult to finalize before the completion of works. This is in terms of cost assessment, man-hours, and material/bills of quantities which need to be measured and adjusted (Al Tamimi 2011). A combined consideration of these factors calls for deliberation and rational decision on the most ideal time to commence dispute resolution processes, not as an act of aggression but as a well-reasoned inference arrived at after a principled negotiation process (Mansoor 2010). This will aid in the identification of issues that are best suited for an amicable settlement, those that require the presence of a mediator/arbitrator or the intervention of the courts

Many disputes can easily be avoided through simple precautionary steps. Such precautionary steps include proper supervision of the construction work and proper management of construction work amongst other steps. However, there is a major need to re-evaluate the construction laws to be equally fair to the various parties in a construction contract. Two editions of the FIDIC red books contain the construction laws used in UAE. In particular, the 1987 and 1999 versions are used in the construction industry. Sections of the FIDIC red books that need re-evaluation include sub-clauses 40.1, 46.1, 69.4 of 1987 FIDIC red book, and sub-clauses 8.6, 7.6, and 13.1(d) of 1999 FIDIC red book amongst other sections (Mansoor 2010; Motsa 2006). Some of the problems associated with these clauses include the authority of the engineer in the construction process, the right of the client in the subcontracting of the third party, and the back-to-back legal provisions

Conclusion

There is a need for legal reforms if negotiation is successful in the UAE’s construction industry. This is because legal issues remain the most challenging aspect of implementing negotiation within the UAE’s construction industry. Such legal reforms are critical if the UAE’s construction is to compete favorably in the global context.

Forms of Negotiation

Introduction

In chapter three, the researcher provided the reader with information regarding negotiation as an ADR mechanism. The researcher covered negotiation in broad and general terms by looking at the various weaknesses and strengths of the dispute resolution mechanism. Given that negotiation is the topic around which this study revolves, the chapter aimed to give the reader an idea of what the general topic is all about. The researcher covered negotiation as an ADR with a bias towards its application in the UAE’s construction industry.

In chapter four, the information will be provided regarding the various forms of negotiation. To this end, the information will be provided regarding distributive and integrative negotiations among others.

Negotiation vs. other Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Mediation and conciliation are increasingly being used in the context of the UAE’s construction industry. The utility of these methods in resolving disputes has undergone massive evolution over time (Mitchell 2000; Heron 1997). Scholars have subjected this literature to diverse reviews and criticisms. This paper is an effort to explore and comprehensively understand their definitions, current practice, suitability, and applicability in the dispute resolution process.

Mediation and conciliation methods are often studied within the context of the broader Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) methods (Stitt 2004; Boserup 2007). According to the Law Commission of Ireland (2010), ADR is a broad spectrum of structured processes. This broad spectrum of structured processes, in which there is the involvement of a neutral third party, and which empowers the parties to resolve their disputes. The spectrum includes mediation and conciliation but excludes litigation although it may be linked to or integrated with litigation in certain specific contexts.

Definitions of Mediation and Conciliation

Much Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) terms enjoy diverse definitions in different academic contexts and usage (Monk & Winslade 2008; Weinstein 2001; Motsa 2006). However, the terms ‘conciliation’ and ‘mediation’ continue to have several definitions that at times fail to portray any differences in their meaning and usage (Smok & Smith 2008; Gartner & Bercovitch 2008). Dowling Hussey as cited by the Law Commission of Ireland (LCI) (2010) captures this dilemma’…the conflicting and contradictory definitions which are used in these two distinct areas tend to create some degree of uncertainty as to what is precisely meant by the phrase’ (p.17).

Some international bodies and academic authorities on ADR methods have sometimes given broad definitions of mediations and conciliation that portray the former as a subset of the latter (Smok & Smith 2008). For example, the 2008 European Council directive on mediation issues one such definition. The council defines mediation as “…a structured process, however named or referred to, whereby two or more parties to a dispute attempt by themselves, on a voluntary basis, to reach an agreement on the settlement of their dispute with the assistance of a mediator” (LCI 2010, p.18). However, the directive later seeks to implicitly distinguish between conciliation and mediation through a caveat in recital 11 of 2008. The recital states that the definition does not apply in contexts where “…processes administered by persons or bodies issuing a formal recommendation, whether or not it be legally binding as to the resolution of the dispute” (Gartner & Bercovitch 2008, p.18).

The above definition of mediation subtly or implicitly implies that mediation is a subset of conciliation from the conceptual definition of the term. However, there are times where one term is used in the definition of the other term (Monk & Winslade 2008). This further fuels the viewpoints that are no distinction between the two terms. One such definition is offered by the United Nations Commissions on International Trade Law (UNCITL) that defines conciliation as:

“… a process, whether referred to by the expression conciliation, mediation or an expression of similar import, whereby parties request a third person or persons (“the conciliator”) to assist them in their attempt to reach an amicable settlement of their dispute arising out of or relating to a contractual or other legal relationship. The conciliator does not have the authority to impose upon the parties a solution to the dispute” (UNCITL 2002, p.1).

This viewpoint is further emphasized in a different UNTIL session in 2007: the Modern Law for Global Commerce in Vienna. Wiwen-Nilsson (2007) in a paper presented for the UNCITIL session the Modern Law for Global Commerce states “…proceedings in which the parties are assisted by a third person to settle a dispute are referred to by expressions such as conciliation, mediation, neutral evaluation, mini-trial or similar terms”(p.2). Several scholars and international bodies continue to define the two terms in a manner that it is difficult to distinguish the differences between them. The National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (NADRAC) (2007), defines mediation as”… a process in which the parties to a dispute, with the assistance of a dispute resolution practitioner (the mediator), identify the disputed issue, develop options, consider alternatives and endeavour to reach an agreement” (p.1). On the other hand, International Labour Organization as cited by Rao (2007) defined conciliation as the practice by which the services of a neutral third party are used in a dispute as a means of helping the disputing parties to reduce the extent of their differences and to arrive at an amicable settlement or agreed solution.

It is critical to note that the UNCITL, Wiwen-Nilsson, NADRAC, and ILO seem to emphasize the existence of a third party in helping the disputing parties reach an agreement. In this context, UNCITL (2002) states the definition of conciliation “…applies irrespective of the name given to the process…there is no intention distinguish among procedural styles or approaches to mediation” (p.21). UNCITL propagates the idea that the difference in procedural styles or approaches does not constitute a distinct dispute resolution method from conciliation. It rather seems to hold the view that any such differences may be different ways of executing the conciliation process. In this context, (Monk & Winslade 2008) state “…conciliation proceeding may differ in procedural details depending on what is considered the best method to foster a settlement between the parties” (p.13). However, UNCITL seems to elaborate on the role of the conciliator in the process in a manner that may be construed to distinguish the term from mediation. UNCITL as cited by Wiwen-Nilsson (2007) states, “The conciliator may, at any stage of the conciliation proceedings, make proposals for a settlement of the dispute” (p.23).

The Law Commission of Ireland (2010) has tried to emphasize subtle differences in the meaning, form, and context of the two terms. LCI (2010) defines mediation as ‘…a facilitative, consensual and confidential process, in which parties to the dispute select a neutral and interdependent third party to assist them in reaching a mutually acceptable negotiated agreement’ (p.17). This definition is supported by Brown & Marriot as cited by Rao (2007). They perceived mediation as a facilitative process in which the disputing parties engage the assistance of an impartial third party, the mediator, who helps them to try to arrive at an agreed resolution of their dispute. On the other hand, Wiwen-Nilsson (2007) defines conciliation as ‘…an advisory, consensual and confidential process, in which parties to the dispute select a neutral and interdependent third party to assist them in reaching a mutually acceptable negotiated agreement’ (p.17).

Differences between mediation and conciliation

The LCI (2010) explained two distinguishing characteristics of mediation and conciliation. The two distinguishing characteristics were the role of the third party in the process and the ‘interest based versus interest based resolutions’ (LCI 2010; (Monk & Winslade 2008). The role and the level of involvement of the third party distinguish mediation from conciliation processes.

The conciliation method allows the third party to make proposals that would lead to the settlement of the dispute (Crawley & Graham 2002). The third party also allows the third party to make formal recommendations to the disputing parties. In this context, the third party is seen to advise on the substantive matter of the dispute issues and dispute resolution process (LCI 2010). Substantive matters infer that the third party may define the rights or duties of the different disputing parties. On the other hand, the third party only addresses the non-substantive matter in the mediation process (Mitchell 2000). In this context, the third party is only interested in the rules of the process by which rights and duties are defined.

In contrast to the conciliation method, the third party in the context of mediation does not define the rights and duties of the disputing parties (LCI 2010; Heron 1997). The views of LCI with respect to the role of the third parties are further emphasized by the NADRAC. NADRAC (2007) views mediation as a purely facilitative process, whereas conciliation may encompass a mixture of processes including facilitation and advice. Consequently, the mediator does not undertake any advisory role in the dispute resolution process, unlike a conciliator who undertakes this role.

It is generally assumed that mediation is an interest-based dispute resolution method in contrast to the conciliation method (Gartner & Bercovitch 2008). In this context, the mediation process addresses the dispute from a holistic perspective. This means that the mediator may be interested in the underlying concerns and interests of the disputing parties. In this context, the mediator may dig deeper into the real motivation of the disputing parties in a bid to create a long-term solution to the problem (Monk & Winslade 2008). On the other hand, the conciliation method is considered more rigid and more interested in the legal rights of the disputing parties. However, all decisions that arrived through the conciliation method may not necessarily be solely based on the legal rights of the parties. Instead, the conciliator when issuing recommendations may also consider the underlying interests of the parties (Weinstein 2001).

Bridge Mediation LLC (2004) introduced another difference between conciliation and mediation. Conciliation is a preventive process and such it is utilized immediately a dispute surfaces (Smok & Smith 2008). The conciliator thus pushes to stop the emerging dispute from escalating into a full-blown dispute. On the other hand, mediation is perceived to be closer to arbitration. This is because it is often used in contexts where the dispute has escalated to a critical level. These are mostly disputes that are almost impossible to resolve without professional assistance. Mediation is thus used in contexts where the dispute has sufficiently developed to its advanced stage that there is a potential of instigation of litigation measures (Heron 1997; Stitt 2004; Boserup 2007). The disputing parties thus resolve to seek an alternative method to intervene in their dispute.

The uptake of mediation and conciliation in the UAE’s construction industry as a means of dispute resolution is not sufficient. There is a preference among the industry stakeholders for the traditional and more established dispute resolution mechanisms such as litigation and arbitration. This may be because these methods offering decisions that are more binding. In this context, the decisions are perceived to be easily enforceable. Within the context of the UAE’s construction industry, there seems to be little attempt to differentiate the two terms. In the context of the UAE’s construction industry, the mediators/conciliators are perceived as neutral parties appointed by both sides to facilitate the negotiations to resolve. The role of the mediator/conciliator is to point out the strengths and the weaknesses of each party’s case and guide the parties in a negotiation process.

Conclusion

The legal provisions in the context of dispute resolution clauses in construction contracts do not differentiate between mediation and conciliation. Mediation/conciliation is the next step towards resolving disputes in the construction industry after negotiation. The mediator/conciliator is expected to be a neutral party. In this context, the mediator/conciliator guides the parties to a negotiation process by pointing out their strengths and weaknesses and strives to promote a win-win situation.

Research Design Methodology

Introduction

In chapter four, the researcher provided the reader with information regarding the various forms of negotiations that are used by stakeholders in the construction industry and even in other industries in the world. The chapter was biased towards the utilization of the various negotiation methods in the UAE’s construction industry.

In chapter five, the researcher will provide the reader with information regarding the steps that were taken in collecting data for the study. To this end, information regarding the research design, the research sample and sampling technique, tools for data collection among others will be provided. The aim here is to give the reader a step by step analysis of the strategy that was used to collect data for the study.

Research Design: Overview

This research is undertaken to gain insights into the negotiation method as a means of dispute resolution mechanism within the context of the UAE’s construction industry. Specifically, the research aims to tackle the research questions earlier discussed in chapter one of this dissertation. To tackle the research questions and fulfill the aims of the research, data must be collected and analyzed in a systematic manner (Golafshani 2003). In this context, research methodologies help the researcher to achieve this.

Three broad types of research methodologies are used in academic research. These methodologies are quantitative research methodology, qualitative research methodologies, and mixed-method research methodology (Ospina 2004; United Nations World Food Programme (2007). Several labels are used to refer to these methodologies in different academic disciplines, contexts, and literature (Ravindran 2008). In this context, several academic terms are used to refer to quantitative research methodology. Such terms include traditional, empiricist, and positivist research methodologies (Golafshani 2003). Another term widely used in this context is the experimental research methodology (Welch & Wood 2010). On the other hand, naturalistic, postmodern, and post-positivist are terms widely associated with qualitative research methodologies (Ravindran 2008). Constructivist and interpretative are also terms associated with qualitative research methodology.

The quantitative research methodology is widely used in researches that involve quantitative data (Ospina 2004). Quantitative data can be loosely perceived as numerical variables. In this context, quantitative research methodology is interested in using numerical variables to probe the stated hypothesis (Ravindran 2008). A wide array of data is collected on the given variables to analyze the trends to gain insights into the research problems and test the hypothesis (Welch & Wood 2010).

The defining characteristic of quantitative research methodology is the existence of variables. In the context of quantitative research methodology, variables can be categorized using two attributes; a level of measurement and the role of the variable in the research (Shaw 1999). Variables can be divided into two categories using the level of measurement as the determinant attribute (Golafshani 2003). These two types of variables are categorical and quantitative variables. The categorical variable takes different values for different categories of the phenomenon under study e.g. gender can only be categories as either male or female (Ospina 2004). On the other hand, a quantitative variable varies in the extent or degree of the phenomenon under study e.g. level of income can vary from zero up to a given finite number.

In the context of the role of the variable in the research, the variable is divided into the independent variable, dependent variable, mediation or intervening variable, and moderator variable (Ospina 2004). The independent variable is the causal variable in the context that it causes a change on another variable. On the other hand, the dependent variable is made to change by an effect of the independent variable (Sprenkle 2005). The mediating variable helps regulate how the independent variable affects the dependent variable.

The quantitative research methodology is divided into experimental research and non-experimental research (Golafshani 2003). Experimental research is often used to study the cause of relationships between variables as well as their effects on each other (Welch & Wood 2010).In this context, the research manipulates the independent variable to understand its effect on the constant characteristic or another variable (Ravindran 2008). On the other hand, non-experimental does not utilize the manipulation of the independent variable; in this context, one cannot conclude on the relationship between variables (Shaw 1999). This is because there may be other factors and issues at play.

The qualitative research methodology is interested in understanding the nature of events as they are in their natural settings (Sprenkle 2005). The qualitative research methodology is often interested in intangible characteristics of a phenomenon under study (Ospina 2004). In this context, the research is interested in understanding beliefs, or experiences. The research may also be interested in understating relationships, ideas, and values.

The major defining characteristic of the qualitative research methodology is the emphasis on studying the phenomenon in its natural settings or environment (Ospina 2004). This characteristic has several implications on the nature and the direction of the research. Qualitative researchers do not set artificial experiments, as is the case of experimental quantitative research (Shaw 1999). However, qualitative researchers may use ‘natural experiments’ in which the researchers change certain aspects or attributes of a natural process in the normal course of its operation (Sprenkle 2005). To the intangible aspects of a phenomenon that is studied, the research tries to be part of the phenomenon in its natural settings in order to gain insights into it.

Qualitative research is divided into ethnography, case study research, grounded theory, phenomenology, historical research, and focus groups amongst others (Ospina 2004). In phenomenology, the researcher is interested in the contexts in which the individuals experience the given phenomenon. On the other hand, ethnography focuses on understanding the culture of the group under study. Case study research involves the study of a given specific case (Ravindran 2008). The specific case is studied to form an understanding of the phenomenon in that sector. In the grounded theory, the researcher collects data from which he extracts a theory (Sprenkle 2005). Focus groups involve the use of panels discussing a given phenomenon under the direction of a facilitator.

Research Approach

This subsection of the chapter will focus on five aspects of the research. The subsection will explain in detail the research methods and data collection techniques utilized for this research. The subsection will also explain the reasons for choosing these methods and data collection techniques. It also explains the advantages and disadvantages of the chosen research methods and data collection techniques. Finally, the subsection will try to explore research methods and data collection methods used by other scholars in the field.

Mansoor (2010) in his study, the application of ADR in the UAE construction industry, uses both qualitative and quantitative research methods. In this context, questionnaire surveys were used to collect quantitative data. Mansoor (2010) justifies the use of quantitative methods in his research as it helps ‘…measure the things that people, events or situation have in common’ (p.37). Mansoor (2010) justifies the use of the qualitative method to gain insights into the subject problem. In the context of primary data collection methods, Mansoor (2010) uses questionnaire surveys and interviews.

In the context of this research, both the quantitative and qualitative research methods were used. There are several reasons why the qualitative research method was used. The qualitative research method is ideal for the subjective insights into a given phenomenon in which there is an emphasis on understanding the intangible aspect of a phenomenon (Ravindran 2008; Rogelberg 2002). In the context of this research, several amorphous and intangible aspects need to be studied. Some of these intangible aspects include insights into several aspects of negotiation as a means of dispute resolution mechanism within the UAE’s construction industry. Such aspects include the obstacles towards utilization of negotiation method, the impact of negotiation outcomes on relationships of various construction industry stakeholders, and the context in which negotiation is utilized within the UAE’s construction industry amongst other aspects.

There are several advantages of utilizing qualitative research in the context of this paper. It enabled the researcher to understand various aspects of the negotiation used in the construction industry as it is perceived and used by the construction stakeholders. In this context, it was easy to have an in-depth study of negotiation as it is practiced in the real world of the construction industry in the UAE. The stakeholders will generate data in terms of how the construction industry stakeholders perceive negotiation. In this context, it was easy to gain unquantifiable data about negotiation in the UAE’s construction industry.

On the other hand, the subjective nature of the information gained through the qualitative method may not be easily generalized across the board. In the context of this research, different stakeholders may give varying responses for the same answer making it difficult to conclude. The degree to which the various answers hold is also difficult to quantify. The quantitative research method was utilized to capture quantifiable data in which the degree to which a certain attribute within the UAE’s construction industry holds is desirable. In this context, the prevalence of the negotiation method as the preferred means of dispute resolution mechanism could be quantified into percentages. There are several advantages associated with the use of quantitative methods in this research (Shaw 1999; Lassonde et al 2009). The quantitative research enabled the researcher to gain quantifiable data on specific attributes of the construction industry in the UAE. It is possible to state to a statistical accuracy the extent to which the studied attribute holds.

Sampling plan

Target population

The target population for this research paper is the construction industry practitioners which include the construction industry workers, construction industry lawyers, consultants, and construction engineers.

Target organization

The target organization for the research includes consultancy firms, engineering firms, and building and construction firms.

Sampling method

A sample is a subset of the target population that enabled the researcher to make conclusions on the use of negotiation in the UAE’s construction industry. Sampling methods are divided into probability sampling and non-probability sampling (Black 1999; Jacobs 2011). The distinguishing characteristic between the two methods is how the sample members are drawn. Probability sampling draws the sample members in a random manner in which each population member has an equal probability of being chosen (Linda 2008). On the other hand, in non-probability sampling, the sample is chosen in a non-random manner(Jacobs 2011; Linda 2008). One of the greatest advantages of probability sampling is that the sample is likely to be representative of the population and as such the research results can be generalized to the whole population(Black 1999). It is also possible to calculate the extent to which the sample differs from the population that is the sampling error (Linda 2008).

Since interviews were used as a means of data collection. It is critical to note that the interviewed persons had to be construction industry insiders and experts in the construction industry (Black 1999). These construction industry insiders and experts are the most knowledgeable members of the population on information relevant to this research. In this context, non-probabilistic convenience sampling methods were used.

In this context convenience sampling methods were used. In particular, the judgment, snowballing, and convenience sampling techniques were used to draw interviewed persons. The snowballing sampling technique relies on asking the construction industry practitioners on persons likely to have a wealth of knowledge on the subject matter (Jacobs 2011). On the other hand, judgment sampling relies on choosing the sample based on the researcher’s judgment on the people likely to know the subject matter (Black 1999). Lastly, convenience sampling relies on picking the most available population member into the sample set (Jacobs 2011).

There are several reasons why the researcher used a combination of three sampling methods to select a sample of the study. The researcher formed an opinion on the construction industry practitioners such as lawyers, construction contractors, and clients that form the ideal sample set. This opinion was formed from media reports on the construction industry stakeholder embroiled in disputes in the recent past. On the other hand, the researcher also asked the construction industry practitioners on the most authoritative figures in the construction industry dispute resolution process. However, having gained the needed names from the snowball and judgment sampling there was a logistical problem of contacting and transporting all the members from the sample list. In this context, convenience sampling was used to pick subjects for interviews from the sample list dependent on their availability, ease of logistical planning to transport them to a central place for the group meeting.

There are several limitations or disadvantages associated with the use of convenience sampling techniques. One of the greatest disadvantages lies in the issue of generalizing results in the whole population. Convenience sampling may not necessarily draw samples that are representative of the population (Black 1999). In this context, the results may not be generalized to the general population.

Time constraints