Introduction

By state time series (RAW), this study will give data on COVID-19 and its claimed influence on patients and hospital capacity. The data in question are published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and are from the archived source Healthdata.gov. COVID-19 is a potentially fatal respiratory illness produced by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Vaccination and commitment to infection prevention methods (e.g., wearing face masks, hand washing, social distancing, isolation of infected individuals) constitute preventive measures. Antigen testing of upper or lower respiratory tract secretions is used to make a diagnosis. Maintenance therapy, antiviral medications, and corticosteroids are all options for treatment.

COVID-19 was identified in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has since spread rapidly worldwide (Li et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 infection produces a variety of disorders ranging from asymptomatic to abrupt respiratory collapse and death. Older age, immunodeficiency, comorbidities, and pregnancy are all risk factors for severe illness. Vaccines have shown some efficacy in preventing transmission and significant efficacy in avoiding severe illness and death. The COVID-19 and U.S. population and hospital workload data under consideration will help bring the issue to the public’s attention.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is easily transmitted between humans. The transmission probability is proportional to the amount of virus to which a person is exposed. The closer and longer the interaction with an infected individual, the greater the danger of viral transmission. Both asymptomatic and sick persons can transmit the virus, making management challenging.

A person with symptoms is most contagious in the days preceding and following their onset, when the virus load in respiratory secretions is highest. The length from the individual who is infected, the number of infected people in the room, the amount of time utilized with infected people, the dimensions of the atmosphere, aerosol-generating movement (such as singing, yelling, or exercise), ventilation in that place of residence, and the velocity and direction of airflow may all contribute the risk mentioned above (Li et al., 2021). All this information adds to the value of the pandemic data. The data on the effects of COVID-19 on patients and hospital occupancy draws attention to the problem and helps to see the actual situation.

Data Description

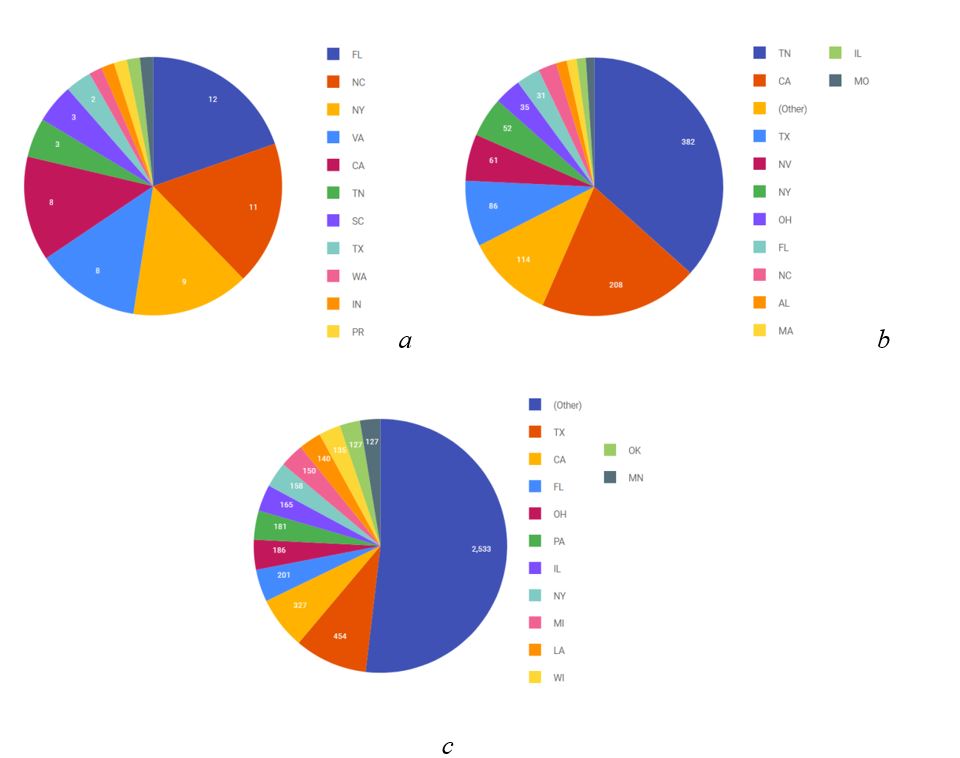

Data collected by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services on health conditions during the pandemic were collected for each state using more than 100 criteria. These include data such as staff shortage, number of beds before and after the pandemic, number of confirmed COVID cases, total number of hospitalizations, number of deaths, and other indicators. Figure 1 shows an example of several criteria for states that were analyzed.

A complete table of 136 indicators can be analyzed in Health Data. According to the database, hospitals in various U.S. states were overburdened with COVID-19 coronavirus illness patients and faced staff shortages. Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Oregon reported a record number of COVID-19 hospitalizations in 2021, resulting in more critical care units and forcing states to seek medical assistance from the federal government. On August 13, 2021, Southern Alabama Governor Kay Ivey issued a state of emergency after local health authorities proclaimed a splash of COVID-19 infections, putting tremendous strain on hospitals (Mock & Kisska-Schulze, 2021). The state of emergency would assist in reducing the workload of healthcare personnel, but he would not impose a lockdown or require the use of masks.

COVID-19 levels in Florida, Mississippi, and Oregon have been reported to be unprecedented. The number of daily cases in the United States more than quadrupled during August 2021, hitting a six-month high, while the average daily mortality rate has surged by 85% in the last 14 days (Wang et al., 2021). Several other states, including Hawaii, have warned about the increased occurrence. Approximately 1,170 additional cases were discovered during the day on August 13, he revealed during a press briefing (Wang et al., 2021).

This is the state’s highest daily rate during the epidemic. The number of hospitalizations in Florida increased by 13% from the previous peak on July 23, 2020 (Wang et al., 2021). According to the state administration, 60% of hospitals will experience “critical staffing shortages” (Wang et al., 2021). Vaccinations offer better protection against reinfection than spontaneous immunity in those who have previously been infected with Covid-19 (Wang et al., 2021). Those infected with COVID-19 but not vaccinated were more than twice as likely to be re-infected as those who were similarly infected but were later wholly vaccinated.

Patients infected with the coronavirus have clogged so many hospital beds in Florida that hospitals and emergency services cannot respond to crises. The number of hospitalizations attributable to COVID-19 in Florida topped the previous pandemic spike, reaching a record of 13,600 cases (Wang et al., 2021). At the peak of last summer’s outbreak, there were about 10,170 daily hospitalizations due to COVID-19. According to the Associated Press, some patients had to wait more than an hour in ambulances for hospitalization instead of the usual 15 minutes (Jánošíková et al., 2021). Nurses in Florida are being poached to work in other states for double and triple pay. State hospitals have been required to pay bonuses to nurses who agree to work with them for a set amount of time.

Nonetheless, Sunshine State hospitals must rely on staffing companies to fill vacancies. According to the Florida Hospital Association, approximately 70% of Florida hospitals anticipate severe staffing shortages the following week. The United States now sees more than 116,000 new coronavirus infections daily, with around 50,000 hospitalizations, a level not seen since the winter COVID-19 outbreak (Wang et al., 2021). This has become an even more significant burden for nurses, who are sick of seeing patients die and incidents of illness.

Changes That Will Increase the Efficiency and Quality of Hospitalization

The advent of COVID-19 and its global dissemination have faced health professionals with problems in the early detection of infection caused by the novel coronavirus, specialized medical care, rehabilitation, and secondary prevention. There is a scarcity of knowledge on primary, secondary, and medical rehabilitation for this condition. Bilateral pneumonia is the most prevalent clinical symptom of the coronavirus infection, with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) developing in 3-4% of patients (Placik et al., 2020). Considering the distinctive nature of the pandemic scenario and the peculiarities of disease pathogenesis induced by SARS-CoV-2, standard procedures may be dangerous or inefficient.

Since the growth of COVID-19 morbidity in the population, the load on the medical system is growing. If the hospital’s workload and the number of patients grow, the institution can increase the number of medical teams and get additional financing. As a result, some hospitals are overcrowded, while others in the area are nearly empty. One cause of this scenario is misaligned patient pathways on a local level, as well as a need for more cooperation between emergency centers and hospitals. Local governments must actively streamline patient routes and ensure an equitable workload for all medical institutions in the region selected to serve COVID-19 patients.

Over the last few decades, the United States government has pushed the treatment transition from inpatient to outpatient settings to save money. Medicaid (for low-income people) and Medicare (for older people) have been essential tools in this quest. Most hospitalizations or continuing medical education are covered by program financing, and the expenses of treating uninsured patients are reimbursed. As a result, even minor changes in payment criteria harm hospitals, which run at a profit of 1-2% each year (Lacik et al., 2020).

According to experts, one of the primary causes of hospital closures in the United States was implementing the Medicare prospective payment system for reimbursing hospital care in 1983 (Lacik et al., 2020). Previously, the government compensated the cost of a patient’s treatment by paying for each medical operation separately; however, the government has since begun to allocate a predetermined sum for treating a patient with a specific diagnosis.

Hospitals had the incentive to treat with the fewest treatments possible, but severe cases needing a significant number of manipulations had an immediate financial impact. Rural hospitals have more challenges than metropolitan ones. As a result, emphasis must be directed to these issues to improve the situation.

The United States has a very unfavorable coronavirus infection status for two reasons: the recent focus on outpatient treatment in the United States and too much disparity in society. The Gini coefficient, the most generally cited measure of inequality, in the “leader” countries in terms of mortality is 35 in Italy, 24 in the Czech Republic, 34 in the United Kingdom, and 41 in the United States (Ghodsee & Orenstein, p. 39, 2021). The coefficient for the world’s “leaders” in the number of new daily infections is Montenegro – 24, the United Kingdom – 34, and the United States – 41 (Ghodsee & Orenstein, 2021). Consider now in more detail the two causes above of the high COVID-19 death toll in the United States.

The statistics analyzed point to two possible explanations for the terrible situation caused by the novel coronavirus infection in the United States, one of the world’s wealthiest countries. First, government policies in the United States closed one-fifth of the hospitals in 1985 (Ghodsee & Orenstein, 2021). The United States government has attempted to shift most medical treatments from inpatient to outpatient care via the Medicare and Medicaid programs to save money.

Conclusion

As a result, when the United States faced a pandemic of a novel coronavirus illness, a lack of hospital beds became an urgent issue. Second, there is a great deal of inequality in America. This gap is predominantly racial in origin, with racial minorities seeing more significant rates of COVID-19 hospitalization and fatality. The found discrepancy among vaccinees is particularly alarming.

While white and Asian Americans get immunized in proportion to their demographic share, African Americans and Hispanic Americans trail significantly behind. At the same time, they compose the majority of professional representatives who supply essential societal functions (Mock & Kisska-Schulze, 2021). Recent events have highlighted its unique characteristics and issues. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the country’s healthcare system’s flaws, such as the consequences of exaggerated outpatient care development at the cost of hospital complexes, excessive commercialization, and the dominance of private healthcare. The pandemic’s “lessons” are anticipated to be implemented in the United States and worldwide.

References

Ghodsee, K. R., & Orenstein, M. A. (2021). Taking stock of shock: Social consequences of the 1989 revolutions. Oxford University Press.

Jánošíková, Ľ., Jankovič, P., Kvet, M., & Zajacová, F. (2021). Coverage versus response time objectives in ambulance location. International Journal of Health Geographics, 20(1), 1-16. Web.

Li, J., Lai, S., Gao, G. F., & Shi, W. (2021). The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature, 600(7889), 408-418. Web.

Mock, R. P., & Kisska-Schulze, K. (2021). Saving the nonessential with radical tax policy. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 90, 197.

Placik, D. A., Taylor, W. L., & Wnuk, N. M. (2020). Bronchopleural fistula development in the setting of novel therapies for acute respiratory distress syndrome in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Radiology Case Reports, 15(11), 2378-2381. Web.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2023). Covid-19 reported patient impact and hospital capacity by state timeseries (RAW). HealthData. Web.

Wang, Y., Hao, H., & Platt, L. S. (2021). Examining risk and crisis communications of government agencies and stakeholders during early-stages of COVID-19 on Twitter. Computers in Human Behavior, 114. Web.