The increased consumption of energy drinks by young people makes health care practitioners and researchers focus on studying the effects of these beverages on the people’s health (Rath, 2012). Much attention is paid to discussing the effects of energy drinks on changes in the heart rate because of threats of increasing blood pressure and developing cardiovascular conditions (Pennington, Johnson, Delaney, & Blankenship, 2010).

According to Pennington et al. (2010), the U.S. scientists found that these beverages “contain enough stimulant ingredients to cause anxiety, insomnia, dehydration, gastrointestinal upset, nervousness, flushed face, diuresis, and accelerated heart rates” (p. 353). However, the previous research in the field demonstrates that there is no single conclusion regarding energy drinks’ effects on changes in heart rate. According to Giles, Mahoney, Brunye, Gardony, and Taylor (2012), there are no exact effects of consuming energy drinks on the pulse rate.

In their turn, Grasser, Yepuri, Dulloo, and Montani (2014) found that components of energy drinks could provoke the increase in heart rate. They found that consumption of energy drinks “led to increases in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure … associated with increased heart rate and cardiac output” (Grasser et al., 2014, p. 1561). Still, in their study, Hajsadeghi, Mohammadpour, Manteghi, Kordshakeri, and Tokazebani (2016) found that the consumption of energy drinks could lead to decreasing the heart rate in young persons.

It is also important to focus on the findings by Wiklund, Karlsson, Ostrom, and Messner (2009) who studied the effects of energy drinks on heart rate associated with exercising. They stated that “post-exercise recovery in heart rate and heart rate variability was slower after the subjects consumed energy drink and alcohol before exercise, than after exercise alone” (Wiklund et al., 2009, p. 74). Significant decreases or increases in heart rate and arrhythmia were not observed, but certain changes were reported.

The purpose of this study is to examine possible effects of the regular consumption of energy drinks on people’s heart rate associated with exercising. For this study, null and working hypotheses are proposed. H0: μ1 = μ2, H0: The heart rate after exercising will be the same for regular consumers of energy drinks and non-consumers. H1: μ1 ≠ μ2, H1: The heart rate after exercising will be different for regular consumers of energy drinks and non-consumers.

It is possible to predict the increase in the heart rate that is typical of most consumers of energy drinks. The reason is that these drinks include stimulants, such as caffeine, guarana, and ginseng among others. Caffeine and other stimulants have specific effects on the organism that are similar to effects of adenosine and adrenaline on the heart rate. Thus, the heart rate increases, and a person can feel anxiety (Grasser et al., 2014; Pennington et al., 2010).

Materials and Methods

For this study, 60 students who consume energy drinks and those who do not consume these beverages were randomly selected from the population of 828 students who had participated in the survey and answered questions regarding their habits. Females represent 62% of all participants, and the participants’ ages range from 18 to 33. Thus, 30 participants who reported that they consume energy drinks and 30 participants who stated that they do not consume these beverages were assigned to two groups.

The experiment was conducted in the controlled environment, an exercise bike was prepared in advance, and the participants were informed about the date and duration of the experiment beforehand. The representatives of each group were asked to measure their resting pulse before the exercise (in beats per minute), ride an exercise bike during five minutes under the researcher’s control, and measure the pulse to conclude about the heart rate again. The results for two groups were compared with the focus on the average heart rate (the mean) before and after exercising. The statistical significance of the received results was checked with the help of a t-test.

Results

The mean in relation to the resting pulse (heart rate) was determined for consumers of energy drinks and non-consumers. Figure 1 demonstrates that the resting heart rate of non-consumers is higher than the rate of energy drinks consumers in about 3.5 beats per minute.

The mean heart rate was also calculated after riding an exercise bike. Figure 2 demonstrates that the rate of non-consumers is higher than the rate of energy drinks consumers in about 4.5 beats per minute.

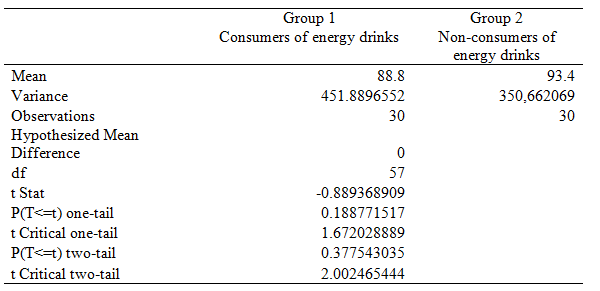

In order to measure the statistical significance of the received results, it was important to conduct a t-test. Table 1 presents the results of the t-test for two groups of participants. It was found that -t Critical two-tail (-2.002) < t Stat (-0.889) < t Critical two-tail (2.002). In this case, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected with reference to the results, and the determined difference in the pulse is not significant to speak about possible effects of energy drink consumption on changes in the heart rate. Hypothesis 1 is not supported.

Conclusion

The purpose of the study was to conduct an experiment in order to measure changes in the heart rate of consumers and non-consumers of energy drinks. The problem is in the fact that the existing literature reports both presence and absence of relationships between consumption of energy drinks and changes in heart rate. The stated hypothesis was not supported, and the results of the study were not predicted.

There was an idea supported by the evidence in some studies that consumption of energy drinks would lead to increasing the heart rate. However, it was found that the average heart rate in non-consumers of energy drinks could be higher than it was in consumers, but there is no statistical significance in the determined differences. Therefore, the results of the experiment indicate that the regular consumption of energy drinks cannot be regarded as the only factor to influence differences in the heart rate and provoke its increase. Other factors, including sex, health, habits, and the way of living should be taken into account.

References

Giles, G. E., Mahoney, C. R., Brunye, T. T., Gardony, A. L., & Taylor, H. A. (2012). Differential cognitive effects of energy drink ingredients: Caffeine, taurine, and glucose. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 102(4), 569-577.

Grasser, E. K., Yepuri, G., Dulloo, A. G., & Montani, J. P. (2014). Cardio-and cerebrovascular responses to the energy drink Red Bull in young adults: A randomized cross-over study. European Journal of Nutrition, 53(7), 1561-1571.

Hajsadeghi, S., Mohammadpour, F., Manteghi, M. J., Kordshakeri, K., & Tokazebani, M. (2016). Effects of energy drinks on blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiographic parameters: An experimental study on healthy young adults. Anatolian Journal of Cardiology, 16(2), 94-99.

Pennington, N., Johnson, M., Delaney, E., & Blankenship, M. B. (2010). Energy drinks: A new health hazard for adolescents. Journal of School Nursing, 26(5), 352-359.

Rath, M. (2012). Energy drinks: What is all the hype? The dangers of energy drink consumption. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 24(2), 70-76.

Wiklund, U., Karlsson, M., Ostrom, M., & Messner, T. (2009). Influence of energy drinks and alcohol on post-exercise heart rate recovery and heart rate variability. Clinical Physiology & Functional Imaging, 29(1), 74-80.