Introduction

Escherichia coli (or simply E. coli) is one of several types of bacteria found in the intestines of healthy people and most warm-blooded animals. E. coli bacteria aid in the maintenance of appropriate intestinal flora (bacteria) balance and the synthesis or production of specific vitamins. A strain of E. coli known as E. coli O157:H7 causes a severe intestinal illness in humans. First isolated in 1982, it is the most frequent strain that causes human sickness. It differs from other E. coli by producing a solid toxin that destroys the lining of the intestinal wall, resulting in bloody diarrhea (Ameer & Wasey, 2022). It’s also referred to as enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection.

Description of the Microorganism

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is a pathogenic bacterium that is mesophilic and Gram-negative rod-shaped (Bacilli). Despite having an incredibly minimal cell structure, with only one chromosomal DNA and a plasmid, it can undertake complex metabolism to support cell growth and division (Ameer & Wasey, 2022). It has adhesive fimbriae and a cell wall of an exterior lipopolysaccharide-containing membrane, a periplasmic gap with a peptidoglycan layer, and an inner cytoplasmic membrane. Fluorescence microscopy can be used to observe E. coli O157:H7 cells after a 10-minute incubation with GFP-labeled PP01 phage at a multiplicity of infection of 1,000 at 4°C.

Virulence Factors

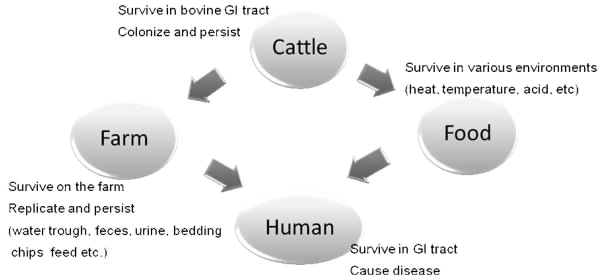

The synthesis of Shiga toxin two and the adhesin intimin are the most critical factors for E. coli O157. Some additional virulence factors, such as enterohemolysin, a serine protease (EspP), and a catalase/peroxidase (Katp), may play a minor role in infection. Unknown virulence qualities, such as a clostridial-like toxin and hemoglobin absorption, require more investigation, and new virulence properties are expected to be revealed. This pathogen thrives in various conditions, including its quiet reservoir in healthy cattle and the agricultural environment. Bacterial adhesion to eukaryotic cells, bovine colonization, and acid tolerance are all influenced by genes encoded on the pO157 (Escherichia coli O157:H7, 2019). Through Tir-mediated and cAMP-independent activation of protein kinase A, Escherichia coli O157:H7 reduces host autophagy and enhances epithelial adhesion. However, the bacteria secrete NleH1, a protein that instructs the host immunological enzyme IKK-beta to change specific immune responses. This procedure not only assists the bacteria in evading immune system destruction but also acts to extend the survival of the infected host, allowing the pathogen to remain and eventually spread to unaffected persons.

Immunity

Escherichia coli O157:H7 Shiga toxins increase the chemokine production of intestinal epithelial cells. This boosts host mucosal inflammatory responses by releasing interleukins, including IL-8 and IL-1, as well as Tumor Necrosis Factor (Escherichia coli O157:H7, 2019). TNF or IL-1 activation of human endothelial cells causes an increase in toxin receptor production and hence greater cell sensitivity, resulting in higher cell death following exposure to the toxins.

Infectious Disease Information

An E. coli infection can cause severe illness. Symptoms often appear two to five days after consuming infected foods or liquids and can persist for up to eight days. It can affect many organs, usually the colon and the kidney. Some of the most prevalent symptoms related to E. coli O157 are as follows: H7 symptoms include stomach pains, diarrhea, exhaustion, nausea, fever, and hemolytic uremic syndrome, which can result in kidney failure and death (Ameer & Wasey, 2022). However, each person may feel them to varying degrees. Long-term follow-up of patients with acute infection would be necessary to determine. E. coli is often considered an opportunistic pathogen because it infects whenever it has the opportunity.

Epidemiology

Prevention

To reduce infectious transmission, isolating potentially infected contacts inside institutions is necessary to prevent the spread of E. coli 0157:H7. A substantial body of research demonstrates that personal hygiene, especially handwashing, significantly reduces the acquisition and transmission of E. coli 0157:H7 infections among the population, changing the risk of HUS. Public health education, standards, and laws to protect food and water against Shiga toxin enterohemorrhagic E. coli can also guarantee safe food production, preparation, and storage which could benefit society (Escherichia coli O157:H7, 2019). The creation of a vaccine that prevents enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection may give herd immunity, protect against HUS, and benefit low-income, high-risk dysentery settings in the future. There are still trials conducted on developing the vaccine (Rahal & Kazzi, 2012). However, in natural exposure situations, vaccination success depends on how the products are employed to limit environmental transmission across groups of cattle and throughout the production chain.

Treatment

The therapy of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) infection is undefined, and whether antimicrobial drugs should be used is debatable. Chemotherapy for EHEC is not widely used in the United States, and the general consensus is that antimicrobial drugs aggravate rather than improve the clinical course of EHEC infection. Antimicrobial drugs have been indicated as a potential risk factor for the development of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in patients with EHEC diarrhea [1-8]. This is because antimicrobial therapy promotes bacterial cell lysis and the consequent release of verotoxins (VTs) (Rahal & Kazzi, 2012). Antimicrobial treatment of E. coli O157:H7 infection is related to an increased risk of serious sequelae such as HUS. The difficulties in treating this bacteria with traditional antimicrobial and chemotherapeutic agent delivery modalities have generated interest in researching novel treatment approaches to this bacterium. These methods have included using probiotic agents and natural items with varying degrees of effectiveness (Rahal & Kazzi, 2012). Usually, scientists test fosfomycin (FOM), minocycline (MINO), kanamycin (KM), and norfloxacin (NFLX) for therapeutic effect because it is suggested that chemotherapy at the early stage of EHEC infection removes the bacteria and lowers the VT level in the colon.

Clinical Relevance

Many earlier investigations have demonstrated the frequency of multidrug-resistant isolates in E. coli O157:H7, with around (33.2% to 100%) of isolates showing multidrug resistance. The incidence of multidrug resistance may be connected to indiscriminate use of antimicrobial drugs or genetic mutation, which the current study methodology could not reveal. Furthermore, meat products have been mentioned as a potential source of multidrug resistance bacteria in Africa. Although E. coli O157:H7 is the most common type of STEC in the U.S., many other types of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli provoke illness in people, frequently referred to as “non-O157 STEC”. These bacteria are dangerous to people of all ages, but the immunocompromised, elderly, and small children are more vulnerable. In addition, currently, the antibiotics used against the MDR strains are polymyxins, aminoglycosides, tigecycline, and many others.

Conclusion

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a gram-negative bacteria found in both human and animal intestines. Most E. coli strains are innocuous, but O157:H7 is a notable exception because it causes severe diarrhea, kidney damage, and other serious problems, including death. E. coli O157: H7 may also cause illness at extremely low doses, persist at low temperatures, and thrive in acidic environments. Further study to understand the mechanisms of E. coli O157:H7 pathogenesis and persistence in the environment will lead to effective interventions to prevent human disease.

References

Ameer M., & Wasey A (2022). Escherichia Coli (E Coli 0157 H7). National Library of Medicine. Web.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 (2019). Johns Hopkins Medicine. Web.

Lim J. & Yoon J. (2020). A brief overview of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its plasmid O157. Web.

Rahal E. & Kazzi N. (2012). Escherichia coli O157:H7—Clinical aspects and novel treatment approaches. National Library of Medicine, 2(138), 106-118, Web.