Abstract

Optimism indicates the extent to which individuals associate favorable expectations with future events. Higher levels of optimism are associated with greater subjective resilience in the face of adversity. Many psychologists measure optimism using questionnaires to analyze hypothetical situations and gain insight into participants’ views of life.

The purpose of this study was to investigate sex differences in optimism and the relationship between age and optimism. One hundred fifty undergraduate psychology majors completed the Revised Life Orientation Test. Analysis revealed that age was not a significant predictor of optimism, as indicated by the Two-Sample t-Test, which reported that women, on average, were more optimistic than men.

Introduction

Optimism is an individual’s cognitive ability to be confident in a positive future and easily overcome any obstacle. Optimistic people have a positive attitude toward the world, are significantly less likely than pessimists to experience stress, and are more motivated to achieve results (Scott, 2022). Given the binary classification between optimism and pessimism, it is of research interest to determine potential sex differences in individuals’ optimism.

It was necessary to determine whether there were more optimists among men than among women. In addition, the relationship between optimism and age proves to be intriguing, and it is essential to examine and determine whether an individual’s optimism changes with age. These findings may be beneficial for psychologists and the medical community to fine-tune the patient interaction experience. In psychological practice, optimism, a human mental trait, is measured using questionnaires that allow one to determine, based on the number of points scored, the respondent’s overall level of optimism (Scheier et al., 1994; Hinz et al., 2022).

Examining academic discourse to identify current knowledge about the research question yields mixed findings. Regarding perceptions of the economic environment, it has been shown that men were more optimistic than women (Bjuggren & Elert, 2019). In other circumstances, when examining the impact of the pandemic, researchers reported that men appeared to be less optimistic than women, with no sex differences found for the financial impact of the virus (Barseghyan, 2020).

Regarding age, it was found that middle-aged individuals were the most optimistic, with younger and older participants exhibiting significantly lower levels of optimism (Bharti & Rangnekar, 2018). At the same time, younger people were shown to be more optimistic than respondents of other ages (van Hekken et al., 2022). The findings suggest that universal inferences about the relationship between optimism and gender and age are not possible, and that context must be considered. The lack of universal conclusions motivates additional statistical research to determine gender and age patterns.

Two research hypotheses were formulated for the two independent variables for this laboratory report. The first null hypothesis was based on the assumption that men are more optimistic or similar to women, and the alternative hypothesis indicates that men are less optimistic than women. The second null hypothesis postulates that age is not related to optimism; that is, it cannot be argued that people of a certain age are more optimistic. Accordingly, the alternative hypothesis suggests that age is correlated with optimism.

Method

Participants

The respondents for this research project were 150 undergraduate students from Brunel University London. Participants of both sexes and various ages were invited to participate in the study as part of an academic assignment, and they completed a questionnaire to measure their personal levels of optimism. The total number of males and females was equal, with 75 of each gender.

In the context of the age, the mean age of the sample was 34.4 years (SD = 10.7), with participants ranging in age from 21 to 63. The mean age of males was 35.6 years (SD = 10.0), and the mean age of females was 35.3 years (SD = 11.4). Consequently, the sex and age distributions in the generated sample did not show significant differences.

Design

This study used a Likert scale questionnaire to collect data, where the participant’s level of optimism was defined as a quantitative value. Statistical analysis was conducted to identify differences within the sample between the two groups, specifically to determine if there were differences in the mean values of optimism between males and females. The sex variable was classified as a nominal dichotomous variable, whereas the age variable was a ratio variable. For the relationship between age and optimism, a Pearson correlation analysis was appropriate because both variables were measured at a quantitative level. The analysis would show whether a relationship existed between the variables and would also indicate the strength and direction of that relationship.

Materials

The Revised Life Orientation Test, consisting of demographic questions (age and gender) and ten questions measured on a five-point Likert scale, was used to collect data in this study (Scheier et al., 1994). The reliability of the questionnaire, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, reached .75 in previous studies, indicating moderate reliability (Hinz et al., 2022). Each response value was assigned a numerical score for both direct (strongly disagree = 0, strongly agree = 4) and reverse (strongly disagree = 4, strongly agree = 0) scoring, after which the scores were summed. In the structure of The Revised Life Orientation Test, three questions were scored by direct scoring, and the same number by reverse scoring. Four questions in the questionnaire were filler questions, so they were not scored in the overall scoring; thus, the maximum number of points a respondent could score was 24.

Procedure

To complete this research project, the university obtained ethical approval, and respondents signed an informed consent form. Each of the 150 respondents filled out a questionnaire, after which all data was recorded in a spreadsheet and analyzed using Jamovi. The results were copied and processed in this laboratory report.

Results

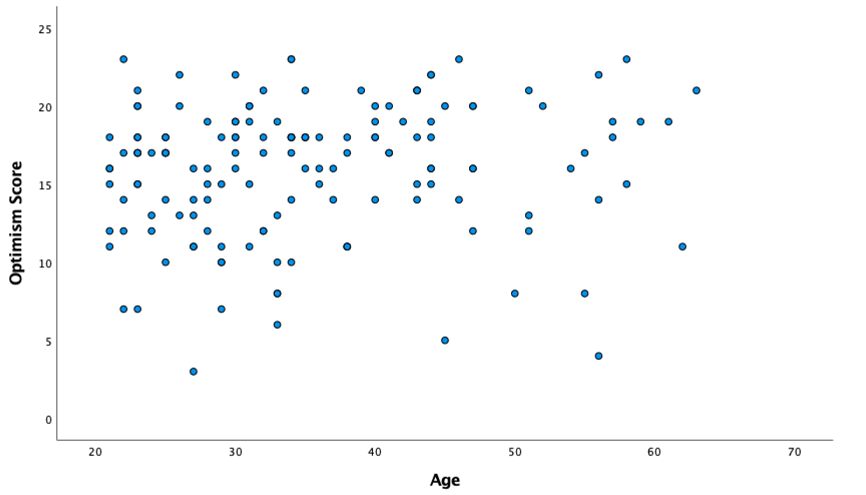

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between age and level of optimism, and to determine the strength and direction of this relationship. The information on the results of this test is as follows: there was no significant relationship between the variables because the p-value was significantly above the critical level of.05, r =.124, p =.131. The lack of a significant trend is also confirmed by the representation in Figure 1, which shows that no linear trend was observed for dispersion. Consequently, the null hypothesis could not be rejected, indicating that age was unrelated to the level of optimism.

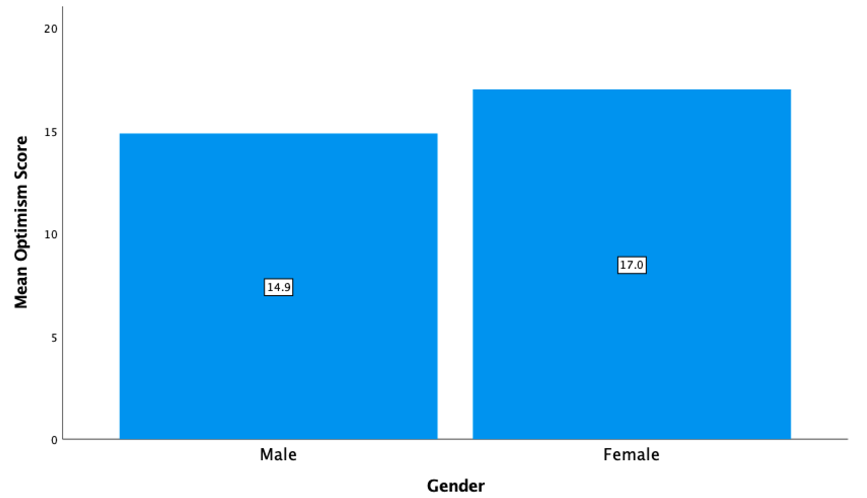

To examine gender differences in optimism, a Two-Sample t-test was administered to determine the significance of differences in the mean scores scored by each gender. The primary concern was determining the mean values; as shown in Figure 2, females scored higher than males.

The results of this test: t(148) = -3.19, p <.001. The null hypothesis was rejected because the calculated p-value was below the critical level. The implication is that statistically significant differences in mean optimism values were found between males and females, indicating that the study demonstrated females were more optimistic than males.

Discussion

This laboratory report aims to investigate gender differences in levels of optimism and the relationship between optimism and age. Statistical analysis revealed no statistically significant relationship between age and optimism, with women being identified as more optimistic. The data are consistent with some studies showing women as more optimistic than men (Barseghyan, 2020).

Other academic discourse data demonstrate opposite trends (Bjuggren & Elert, 2019). It follows that the present project supports only some academic work. Scientific evidence, including that based on the Revised Life Orientation Test (Hinz et al., 2022), supports the lack of age-related effects.

The present laboratory study’s strengths include a large sample size (N = 150) and a high representation of ages. Weaknesses include the narrowing of the sample’s range of gender identities and the lack of testing for a potential Hawthorne effect, which can lead to skewed results. Addressing the limitations is part of the project’s ongoing development. In addition, a substantial sample expansion is proposed, and differences in pessimism are assessed to determine whether men are more pessimistic than women. Current limitations could be addressed by conducting a preliminary focus group and evaluating the questionnaire’s validity.

Conclusion

In this lab project, I had the opportunity to practice using statistical tests to re-evaluate hypotheses. I found that optimism is more prevalent among women than men among Brunel University London graduate students. In addition, there was no correlation between age and optimism, indicating that both adult and young students could be equally optimistic.

References

Barseghyan, G. (2020). Gender differences in optimism during the coronavirus outbreak [PDF document]. Web.

Bharti, T., & Rangnekar, S. (2018). When life gives you lemons, make lemonade: Cross-sectional age and gender differences in optimism. Evidence-Based HRM, 7(2), 213-218. Web.

Bjuggren, C. M., & Elert, N. (2019). Gender differences in optimism. Applied Economics, 51(47), 5160-5173. Web.

Hinz, A., Schulte, T., Fink, C., Gómez, Y., Brähler, E., Zenger, M., & Tibubos, A. N. (2022). Psychometric evaluations of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R), based on nine samples. Psychology & Health, 37(6), 767-779. Web.

Scheier M., Carver C., & Bridges M. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063-1078. Web.

Scott, E. (2022). What is optimism? Very Well Mind. Web.

van Hekken, A., Hoofs, J., & Brüggen, E. C. (2022). Pension participants’ attitudes, beliefs, and emotional responses to the new Dutch pension system. De Economist, 170(1), 173-194. Web.