Introduction

A common perception in society, when looking at what it means for a company to be successful, is that it should be looking to globalize to achieve greater market growth (Rossum, 2015). It is suggested that a business should be scanning opportunities across the globe in order to respond and ultimately expand into that space (Verbeke and Asmusson, 2016).

A global firm is defined by Rugman and Verbeke (2004) as one which has more than 20% of its sales in each of the triad regions and no more than 50% in one region. Whereas a home region-oriented firm will have more than 50% of its sales take place in the home region (Rugman and Verbeke (2004).

A region in this context is a collection of countries, often in close geographic proximity to one another, that are most commonly connected by political agreements created following large-scale shifts in global political power that create a regional trading bloc (Barbieri, 2019). Some examples of regional trading blocs include the European Union (EU), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). A regional strategy, therefore, is one in which a business undertakes expansion into its own region, as opposed to expanding globally – outside of its home region.

The Regional vs. Global debate is the discussion regarding which of these strategies is preferred as a way for a business to expand outside of its home nation. This report will therefore aim to understand the different approaches to regional and global expansion through strategy, and how they can be implemented by multi-national enterprises (MNEs) dependent on the company structure and how they wish to operate internationally. The report will conclude by recommending one strategy as being superior for companies looking to expand out of their home country.

Global vs. Regional Strategies for International Expansion

Globalization, it is argued, has been somewhat stalled by the introduction of the regional bloc, and regionalization has therefore become seen as a viable alternative to globalization according to academics (Ghemawat, 2005). However, there are still clear reasons that globalization could work for a firm, in the form of three common benefits identified by Rugman and Verbeke (2004). The first benefit is economies of scale – where a business concentrates specific activities in one location in order to bring the cost of these activities down. The second, is economies of scope, where resources are shared across borders, especially knowledge-related resources such as shared accounting and ICT. And third, economies of exploiting national differences – which sees the distribution of the value chain across borders, and then coordination of the geographically dispersed activities. However, these 3 benefits are not always simple to gain in reality (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016).

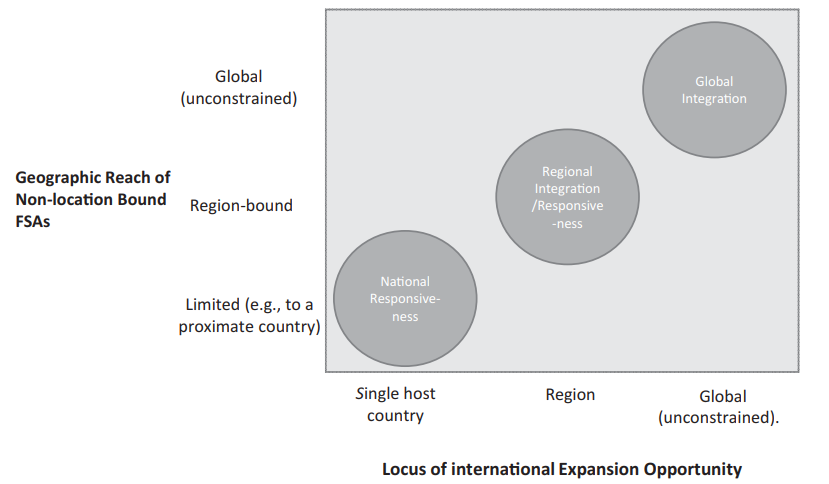

Existing and mainstream research on international strategy has focused on the bottom left and top right of Fig.1, namely the National Responsiveness framework, which emphasizes the importance of remembering that distance between countries still matters (Ghemawat, 2001), and Global Integration, which draws attention to the opportunity and needs to create global strategies (Tallman and Yip, 2001). It is argued that understanding opportunities and therefore careful identification and selection of how and where a business should expand, is integral to profitable growth (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016).

Further research has therefore developed to understand the middle section of the matrix, identified as Regional integration (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016), which has been designated as the sphere of semi-globalization (Ghemawat, 2007) as being a potential avenue for firms to expand without encountering potential disadvantages that come from globalization (Ghemawat, 2005). Hence, according to Verbeke and Asmussen (2016), the region should be a distinct third geographic level of analysis, therefore untied from the national level and the global one.

This conclusion is underpinned by the experience of big corporations such as Nestle, which efficiently addressed the need to balance the needs of the home market and issues stemming from the ongoing expansion of the business. On the one hand, the intended decentralization required reorientating the manufacturing process due to the differing tastes of their customers in the countries of operation (“Nestle case study in international business strategies,” n.d.).

Initially, its failure to do so led to significant losses in most markets. On the other hand, the idea to minimize the role of information technology did not correspond to the actual production needs and contributed to the emerged problem (“Nestle case study in international business strategies,” n.d.). Nevertheless, it was solved through the development of a resource planning system, the GLOBE (Global Business Excellence), which helped to standardize the activities and thereby regain control over the outcomes (“Nestle case study in international business strategies,” n.d.). Hence, this solution can be viewed as an example of an appropriate policy.

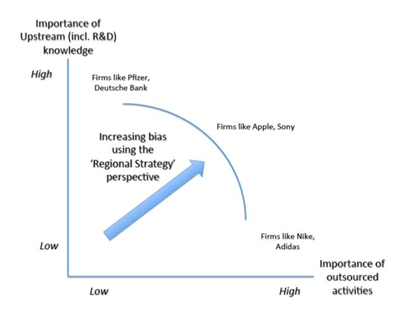

However, the greater research community does not totally agree on the way MNEs are assessed for their strategy. In fact, the regional vs. global debate consists of the fact that the ‘regional strategy’ literature lacks a holistic approach to assessing MNEs’ activities which express the degree of globalization, thus Mudambi and Puck (2016) argue that while sales and production activities of the MNE are regionally structured, as shown by the literature, this conclusion is biased for two reasons: firstly, the focus should not be solely on the geographic location of downstream activities and secondly this approach does not capture the value created from outsourcing activities (Mudambi and Puck, 2016).

If on one hand, the world is ‘flat’ theory believes in a decrease of differences between national and regional dimensions (Friedman, 2006), on the other hand, it has been demonstrated how in fact the world is ‘spiky’ on many dimensions: form innovation to local economic outcomes. Therefore, the general belief is that MNEs can overcome these differences and operate in a fully global fashion (Barlett and Ghoshal, 1993).

Furthermore, the debate takes place also because there is not a commonly agreed definition of the term ‘global operations’, therefore the literature developed by Verbeke and Asmussen (2016) and Rugman and Verbeke (2008) does not take into account the global value chains (GVCs), inside and outside a firm’s boundaries (Mudambi and Puck, 2016).

Hence as anticipated earlier, the contribution to this discussion made by Mudambi and Puck (2016) is twofold:

- It questions the traditional sales-based approach to measure a firm’s diversification, therefore the focus on just downstream activities do not consider the upstream one such as knowledge creation. This argument is made assuming that the current global economy is increasingly dominated by GVCs and that it is required to analyze all the components of the activities. Hence, just considering the sales, it is missed the real ‘global footprint’ of the firm, therefore is important to give to knowledge-based approach a fair weight while assessing the strategy (Mudambi and Puck, 2016).

- It questions the inability to consider the whole range of activities outside the firm’s boundaries that contribute to value creation, for instance, outsourcing. Since most of these external activities take place in regions other than the home region, it comes licit to question whether the externalization should contribute to the firm’s global strategy assessment (Mudambi and Puck, 2016).

In other words, value chain components taken individually can be local or regional, however, if considered as a whole might increase the degree of globalization of the firm. Furthermore, this concept can be also applied to the firm activities, including support one (R&D, HR) and external one. Therefore, as shown in figure 2, the bias while using just a ‘regional strategy’ perspective, increases depending on the Importance of Upstream knowledge and the Importance of outsourced activities (Mudambi and Puck, 2016).

There are dangers presented when a business becomes global. The MNE can encounter liability of foreignness when it ventures outside of its home country (Asmussen, 2009). There is a discussion that liability of foreignness exists also in the home region – except in the home country, but that it is significantly higher outside of it (Asmussen, 2009).

There is also a significant danger of overstretching – overstretching would occur when managers have wrongly judged the extent of the ability of a firm to transfer and deploy its goods and services, or relied too heavily on the incorrect belief that the business would be profitable overseas, perhaps in wrongly assuming the product is fit for more markets than is realistic (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016).

There are other ways that a business can overstretch, Verbeke and Asmussen (2016) also identify overstretching to potentially mean that the geographic scope of the firm’s activities is too broad for efficient control over all aspects, as initially, control would have only been set up for a small geographic area, namely the home country of the business; or, the business is actually location bound in some aspects, and those aspects were overlooked when planning expansion.

A region can be defined as a group of countries that are relatively similar to each other and relatively dissimilar to countries in other regions (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016). As identified by Ghemawat (2007), Regional Integration shown in Fig.1 can also be considered semi-globalization. To assess semi-globalization, two approaches can be taken, the first is that Foreign Strategic Advantages (FSAs) are region bound, in that the potential of moving outside of the region and exploiting advantages is limited and the second, which is similar to the first approach, but focuses on how firms that have already expanded outside of their home country, adapt to the barriers that still exist between regional and global integration in their host region (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016).

An MNE considers distinct geographical scope options with the purpose of achieving the most effective operational process and recognizes that it is necessary to distinguish local, regional and global options to create a comprehensive insight (Asmussen, 2009). It is possible to outline the classification of firms as host or region oriented, which indicated the direction, enterprises tend to move to and explain their representation as mostly belonging to one or another of the mentioned levels.

One of the MNE’s geographical scope options is the subsidiary level, which complements the global option and forms an additional layer of complexity filled with the regional approach. This method is an essential method of spatial coordination, which also links the local to the global. The regional level is considered the most valuable and comprehensive due to its significance in connecting subsidiaries to headquarters and the general impact of the provided within this dimension of service and goods. (Asmussen, 2009).

International Strategies of British Airways

Careful planning of international business expansion for recovery from different crises is an important stage allowing companies to benefit from globalization in the long run. As can be seen from the experience of large enterprises such as British Airways, it can be extremely advantageous in terms of providing solid grounds for growth while increasing the scope of activity. In this way, the opportunities across the globe are efficiently used for the specified objective (Verbeke & Asmussen, 2016). Meanwhile, there are specific risks deriving from the possibility of decreasing the performance of regular operations in this case. In order to avoid them, it is critical to adequately assess the threats accompanying these initiatives, which were also considered by this company while expanding its activities abroad.

Thus, British Airways, which has been seriously affected by the global financial crisis and the subsequent economic recession, managed to adopt effective tactics to overcome the mentioned obstacles to successful work. It developed the Global Premium Airline strategy in order to maintain its leadership position in the markets. This initiative implied enhanced cooperation with partners around the world and conducting a cost-reducing policy (“International business strategies project report,” 2020). In other words, the elaborated measures were aimed at both external and internal conditions, which should be improved for the future promotion of realized services.

The attempts of British Airways to combat the challenges deriving from the crisis circumstances were complemented by planning for the future. The overall strategy in this regard included the need to work with competitors while performing international operations and readjusting the costs in accordance with economic trends (“International business strategies project report,” 2020). This decision allowed the carrier to drop £597 million in fuel costs in collaboration with Iberia and American Airlines (“International business strategies project report,” 2020). Therefore, it was beneficial for both the company and its partners in the long run.

Conclusion

It can be suggested that the view that globalization is the best path for a firm is not entirely supported by the evidence, and the emergence of the Regional Approach provides some doubt as to whether we are living in an increasingly globalized world at all. The experience of large corporations such as Nestle and British Airways proves that the globalized approach can be advantageous only if particular conditions are met. More specifically, this policy should be complemented by measures intended to improve the position in the home markets in the first place. In this situation, the similarity between the measures taken by the companies is connected to the focus of both enterprises on the need to improve internal procedures while addressing external threats and creating opportunities for promotion.

Internationalization is mostly unconstrained within the home region of the firm as regional integration is strong enough to allow it (Asmussen, 2009). Therefore, it can be suggested that it would seem important for firms to introduce a regional strategy to take advantage of this somewhat, easier approach to expansion. Furthermore, regions work well internally but are less homogenous with other regions (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016). So, for example, the countries within the EU are likely to work well together but working then with countries within NAFTA would be much more difficult – due to cost and the liability of foreignness that comes with expanding globally (Asmussen, 2009).

Rugman and Hodgetts (2001) argue simply that regional firms will perform better than global firms, however, it can be suggested that there are limitations to the Regional approach. Firstly, within the literature. Mudambi and Puck (2016) argue that the literature does not capture all of the MNE activities, focusing too much on downstream activities, and not enough on knowledge creation and other upstream activities. Also, the regional approach only looks at internally created value, and not value created by the external activity.

Whilst Verbeke and Asmussen (2016) state that MNEs have a stronger home region bias when they are expanding, Rugman and Verbeke (2008) originally state that this differs depending on the type of business – with services having a stronger home-region orientation than businesses that are primarily manufacturers for example.

Furthermore, if the world is becoming increasingly flat, then it would still be the best option for a business to initiate a global strategy with a product that is able to be standardized, which is particularly relevant for manufacturing firms where economies of scale are already exhausted at the national level, but to be successful, the international strategy needs to combine already held resources with new resources in a host country to then create a new, location bound FSA (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016).

In conclusion, it can be suggested that different approaches would work better for different types of firms, however, to decrease the chance of encountering the dangers of globalization, taking a regional approach may be beneficial for firms that wish to create more locally specific products (Verbeke and Asmussen, 2016).

It is recommended however that further research should seek to address the limitations of regional strategy literature as identified in this report and through the work of Mudambi and Puck (2016), showing that there may be bias shown towards regional strategy through different approaches, namely a knowledge/resource-based view, internalization theory, or simply transaction cost economics when it comes to a business’s international expansion.

References

Asmussen, C. G. (2009). Local, regional, or global? Quantifying MNE geographic scope. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1192-1205. Web.

Ghemawat, P. (2003). Semiglobalization and international business strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(2), 138-152. Web.

International business strategies project report. (2020). Ivy Panda. Web.

Nestle case study in international business strategies. (n.d.).

Verbeke, A., & Asmussen, C. G. (2016). Global, local, or regional? The locus of MNE strategies. Journal of Management Studies, 53(6), 1051-1075. Web.