Background

Homelessness exists in almost all countries, including democratic, economically developed states. According to Dobrovic et al. (2021), Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane are among the cities in Australia affected by homelessness, amounting to more than 100 000 people with no secure place to live or sleep a day. Poverty, alcoholism, and mental illness are significant causes of voluntary homelessness in these cities. 18% is accounted for spousal violence and cruelty, flight from drunken brawlers; illness, senile incapacity, and dementia; an extract from the living space of one spouse to another, their relatives after filing a divorce; deception during a related exchange.

Homeless crisis support has been in place for years to help homeless people acquire a stable and secure shelter. The problem of homelessness is one of the most acute social problems in modern Australia, but at present, it cannot be objectively assessed in full (Dobrovic et al., 2021). The reason for this is the lack of accurate and timely statistics on the total number of homeless people and the effectiveness of the homeless crisis support. Such indicators as the number, experience of homelessness and the quality of life of the homeless, the availability, development, and effectiveness of mechanisms for adaptation and rehabilitation, and the attitude of the authorities and society towards the homeless are a kind of indicators by which one can judge how acute and neglected the homeless are (Dobrovic et al., 2021). Thus, the study will study the impacts and effectiveness of homeless crisis support in Australia.

Research Questions and Aims

The study aims to research home crisis support, its effectiveness, and its impacts on reducing homelessness in Australia. An important step can be recognized as an attempt at the local level to discuss the possibilities of helping the homeless with several stakeholders’ participation, highlighting the difficulties that arise and finding a joint solution (Young & Petty, 2019). The following questions will assist the research on the focal study on homeless crisis support.

- What are the main activities of Homeless Crisis support?

- How practical is homeless crisis support in reducing the effects of homelessness

- What are the impacts of Home Crisis support in reducing the homeless rates in Australia?

Literature Review and Background to the Issue

Background

Homelessness has many facets. For some, it is far away. For others, it is an inevitable part of life; another chooses it out of conviction, and the next fights against it. Centers for Social Adaptation of Homeless People have been active since the number of homeless people began to grow in the city. The institution’s activities are aimed at the social rehabilitation of the lost and their integration into society to create conditions for overcoming adverse life situations and reducing social inequality. Of every 10,000 Australian residents, 108 require help that qualifies for homelessness status. 1.1 % of the Australian population are deprived of a clean bed, free lunch, medical care, and sanitizing their living conditions. Around 20,000 children and young people live on the streets, 9,000 of them. People living on the streets are a subgroup of homeless people, whereby the number of homeless people living in Australia is assumed to be 254,000, of which around 76 percent are single people. These people need help to solve the issues of employment, pension provision, medical care in the hospital, and financial assistance.

Initiative groups of citizens and social movements organize feeding the homeless, and when establishing interaction with state and municipal services, the homeless are sent to them (Young & Petty, 2019). Social movements and commercial and non-profit organizations are the essential links in helping people who find themselves in a difficult life situation associated with homelessness receive the necessary public services. Often the mediation and intercession of NGOs is the only way to get a response from the state system (d’Abrera, 2018). In the absence of a state program for the social rehabilitation of the homeless, the efficiency of social assistance depends solely on personal qualities.

Literature Review

Various studies have dedicated their effort to studying the changes in homelessness and the evolution of homeless support capabilities. According to Batterham et al. (2021), various homeless crisis supports organizations such as the red cross and ACT community services are prevalent among people without a fixed place of residence and occupation. According to d’Abrera (2018), people quickly get used to cleanliness and warmth and, for the most part, try to get out of the difficult situation they find themselves in. In case of violation of the rules of residence, mainly alcohol abuse, preventive conversations are held with them by medical workers of the institution.

Overall, there is little empirically verified knowledge about the effectiveness of homeless crisis support. This decline mainly results from investigations within the psychosocial area under the aspect of poverty. (Sadler & Mongoo, 2021) investigated life without one’s own living space to record homeless people’s living conditions, including health prospects. With hermeneutic, descriptive methods, and methods of empirical social research, homelessness as a ‘phenomenon’ in its actual existence is investigated, administrative consequences are worked out, and homelessness as a social phenomenon is theoretically explained by sociology. Tedmanson et al. (2022) ascribe an essential task to helping the homeless in their studies context. He points to an extremely high proportion of special needs in homeless residential areas and describes the unstimulated environment as a causal factor for poor living standards.

Homeless people examined are people who live in shelters, including emergency shelters and modest apartments, which is why the information should be carefully considered for relevance to people living on the streets. Batterham et al. (2021) interviewed homeless people living on the streets in 117 homeless and drug help facilities in Sydney to obtain basic information about this group. This quantitative study involved women-specific questions raised qualitatively through expert interviews. The focus of the study was on the factors affecting homeless people and the help they get without much concern for the effectiveness and the impacts. He sees the cause as “that life on the street requires a high degree of anonymity and flexibility on the part of those affected so that the daily routine and the selection of sleeping places by homeless people is hardly transparent to external viewers” and therefore describes these people as an elusive social ‘phantom.’

Casey and Stazen’s (2021) study, in connection with the censuses from a different year, was a pioneer in knowledge acquisition. At that time, there were only very few empirical studies on people living on the streets that were representative of the entire cities (Gaetz, 2018). It was impossible to reach people who did not take advantage of institutional help, had no contact with the institution concerned during the survey, or declined an interview (Gaetz, 2018). It is an area where only rudimentary, reliable empirical information is available, given the pluralism of terms within the shelter or homeless system (Casey & Stazen, 2021). Thus, the study finds a gap in the literature that provides crucial information on the effectiveness and impact of Homeless crisis support from the view of the homeless.

Methods

Various methods will be used to attain the needed information to answer the study questions. The study will use a qualitative research design meaning a non-numerical approach will be applied. Qualitative research is crucial in such a social-related study as the researcher is free to use methods such as observation and interaction with participants to understand them more (Kuskoff, 2018). Another rationale for using the qualitative design is the adaptability factor, such that the author can change the research flow to accommodate new findings (Kuskoff, 2018). The data gathered will therefore fall in the category of primary qualitative. According to Akinyode and Khan (2018), primary qualitative data is oriented socially with the interconnectedness of social phenomena rather than a discrete orientation.

To collect the data, a primary method will be used. Primary survey tools are methods applied in research that contain a set of open questions that the participants can fill freely. Ten questions will be set connecting the aim of the study and the research questions. The content of the survey is to be examined on the subject of accommodation of the homeless and the social and economic support given to the homeless (Clarke et al., 2020). Since the background of the homeless support can be offered from a different social and economic point of view and appears relatively similar in terms of the situation, the questions will be diverse to cover more areas (Akinyode & Khan 2018). The questions will collect the participant’s views, emotions, and feelings towards the homeless crisis support. Additionally, interviews will utilize interviewer and interviewee contact and avoid missing crucial information (Clarke et al., 2020). The researcher will travel to different locations in Sydney with homeless participants and ask them the intended questions.

The participants of the study will be the homeless community in Sydney city. Since this is a qualitative study, a minimum of 50 participants will be valid in getting the needed information. Most homeless people are very protective and do not engage in questions; thus, snowball sampling is a qualitative method where referrals with the same characteristics or conditions refer their fellows to the study. Purposive sampling is a method used by researchers to sample non-probability samples and judge which participants qualify to be in the study. An observation will be done to identify the homeless in the city before approaching. A reward will be used to ensure that the researcher can get enough participants. Most studies rely on information from support groups and leave vital information from the affected population.

In addition to the methods mentioned above, the secondary data collection method will be applied to facilitate integrating the research into this study. In this method, the researcher will be required to analyze data from sources such as magazines, newspapers, books, and journals. For instance, the Parity Journal, one of the famous journals for social science articles, can be a helpful source of information based on Australia’s state of homelessness. Besides, secondary data is crucial in saving time and money needed for the research as a significant proportion of the study is already done and only requires analysis. Additionally, secondary data facilitates building upon the current research, which typically translates to better results (MacKenzie, 2018). Therefore, this study will analyze sources such as journals, public records, and government publications, among others, using the secondary data method.

The Data analysis method to be used will be thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a qualitative method that finds themes and meanings in qualitative data. SPSS will be used in analyzing the thematic relationship of the participant’s response (MacKenzie, 2018). The researcher, understanding the laid objectives, will set themes such as “Effective homeless crisis support” and “helpful homeless crisis support” to find the conclusive meaning of the interviews.

Ethics

Ethics are Ethical considerations that form a background of reliable and valid research, and thus the study will consider them.

- The study will use interviews, and contact with human participants will be done. Thus, formations of questions will be considerate of emotions intruding on questions that could affect the psychological well-being of the participants. Too personal questions will be avoided any potential harm.

- The study participants’ consent will also be sought to uphold voluntary participation. According to Dobrovic et al. (2021), it is against ethics to use people’s information without their consent.

- Data protection and privacy will also be considered in the study. Data information should only be used for the intended study. It will be protected from external use—termination of the data after the study period as accorded by research ethics. In data protection and privacy, the anonymity of the participants will also be upheld by not asking for or distributing personal information.

- The results of the research will also be communicated without bias. It is ethical to disclose the study’s findings to the relevant people, including the participants, without altering them.

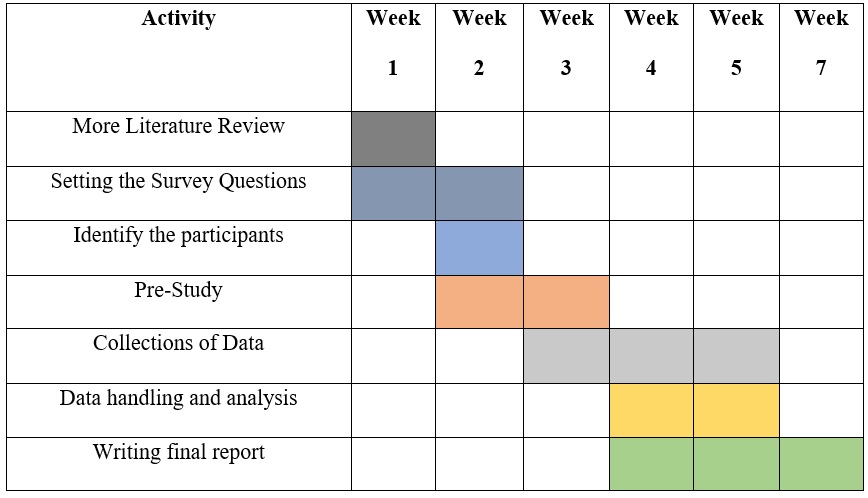

Timetable

A timetable is crucial for the researcher to manage their time and accomplish all the research objectives. The following is the proposed timetable for undertaking the research.

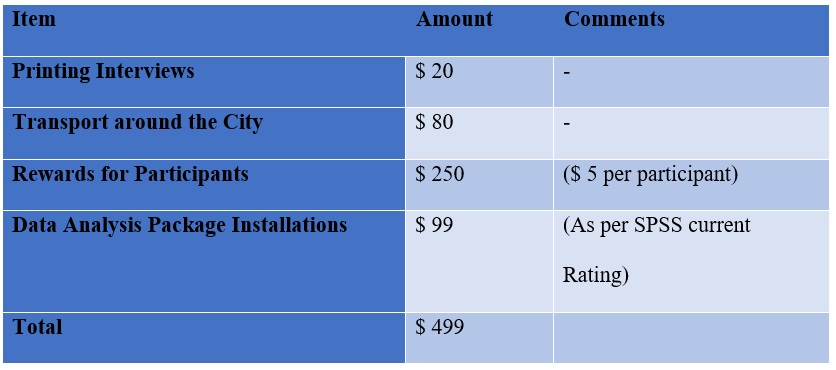

Budget and Resources Required

To carry out a comprehensive study, there are some incurred costs. The costs projected and budgeted by the study are summarized in the table below.

Dissemination of the Results

Dissemination of a study is the process of ensuring that the target audience. According to Dobrovic et al. (2021), one of the most crucial skills for a researcher is disseminating a study’s findings. There are different ways of disseminating research findings, including publication, presenting to the affiliate school, and preparing a presentation for the intended shareholders. The study will research homeless crisis support, which means that its contribution is intended to understand the impacts and effectiveness of homeless crisis support. The study also intends to use the homeless as the data source; thus, most stakeholders will be interested in the report. Findings from studies must be made public for various present-day and future use. After the study results and the structuring of the report, it will be reported to the school and later published for social science use. The stakeholders for the final report will include the homeless crisis support governmental and non-governmental organizations, the social science research webs, and current and future researchers.

References

Akinyode, B. F., & Khan, T. H. (2018). Step-by-step approach for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of built environment and sustainability, 5(3), 1-8.

Batterham, D., Parkinson, S., Wood, G., & Reynolds, M. (2021). Homelessness in Australia’s capital cities. Parity, 34(4), 5-7.

Casey, L., & Stazen, L. (2021). Seeing homelessness through the sustainable development goals. European Journal of Homelessness, 15(3), 34-67.

Clarke, A., Watts, B., & Parsell, C. (2020). Conditionality in the context of housing‐led homelessness policy: Comparing Australia’s Housing First agenda to Scotland’s “rights‐based” approach. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 55(1), 88-100.

d’Abrera, C. (2018). Dying with their rights on the myths and realities of ending homelessness in Australia. Routledge.

Dobrovic, J., Vallesi, S., Hartley, C., & Callis, Z. (2021). Ending homelessness in Australia. Routledge

Gaetz, S. (2018). Reflections from Canada: Can research contribute to better responses to youth homelessness?. Cityscape, 20(3), 139-146.

Kuskoff, E. (2018). The importance of discourse in homelessness policy for young people: an Australian perspective. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(3), 376-390.

MacKenzie, D. (2018). Some reflections on the policy history of youth homelessness in Australia. Cityscape, 20(3), 147-156.

Sadler, J., & Mongoo, N. (2021). Domestic and family violence and homelessness in remote Western Australia. Parity, 34(10), 62-63.

Tedmanson, D., Tually, S., Habibis, D., & Chong, A. (2022). Urban Indigenous homelessness: much more than housing. Routledge.

Young, A., & Petty, J. (2019). Urban conviviality and public homelessness: A new research agenda. Parity, 32(7), 47-48.