SME lending policies of the British banks before and after the financial crisis

The financial crisis that almost brought the world’s economy to its knees in 2008/2009 has left many economies struggling and led to radical changes in the financial sector (Dullien et al. 2010, p. 113). As countries take precautions not to land in a similar situation in the future, their target has been a financial institution, which, according to economists, were responsible for the economic downturn (House of Commons Treasury Committee 2009, p. 13). As a result, many stringent measures have been imposed on financial institutions by various governments to guard against any future economic meltdown resulting from financial institutions’ missteps. The British government has not been left behind in this, as it bailed out many banks after making mistakes many critics have considered a result of poor managerial decisions and greed. The introduction of these stringent measures has been met with criticism and support in an almost equal measure. However, given the extent of the damage caused by the 2008/2009 financial meltdown, the action was necessary. To find out if the financial crisis actually changed commercial banks’ lending policies to SMEs, a simple econometric analysis of the commercial banks’ collateral requirement, debt rejection, and even arrangement fees will be analyzed for the period preceding the crisis and after the crisis and conclusions drawn from the findings.

Before the financial crisis, SME lending policies were both relaxed and easily attainable. Many financial institutions operated as though they were not being regulated. Consequently, many SMEs got access to capital for expanding operations, overdrafts for meeting short-term financial obligations, hire purchase and leasing arrangements for acquiring the services of large equipment and machinery, which are expensive to acquire, venture capital for exploiting newly found avenues considered viable, and equity bonds to further operational activities. This ease of access to loans was enabled by several factors. Before the crisis, many financial institutions flexed and eased their loan issuing requirements to attract more SMEs to their pools of funds for lending (Hardie & Maxfield 2010, p. 9). A few years that preceded the financial crisis saw a sharp increase in money in circulation in the world. Nations that were poor now had money from sales of oil and other petroleum products and had to seek investment opportunities. Property investment became the most viable option, pushing property prices in western countries and America extremely high. With the excess money, banks could satisfy all eligible loan applicants, and still be left with excess cash. This excess fund made banks lower their lending rates and regulations to attract people who would have been otherwise left out due to a lack of securities. For instance, collateral requirements were significantly lowered to attract many small and medium-sized enterprises that lacked sufficient collateral, property, or equipment, to enable them to access the loan facilities. Mortgages were issued overnight and investigations that are traditionally carried out to ascertain eligibility became irrelevant. In fact, it has been reported that there were incidences where people with no stable jobs could walk into a banking hall and walk out with a mortgage. No financial background checks were made.

The boom in mortgages contributed to a tremendous growth in SMEs operating in complementary sectors. Financing for these emerging and existing SMEs was not a challenge as banks had vast amounts of money that had to be issued out to earn at least something than lie in the banking halls. SMEs’ balance sheets and credit worthiness mattered little, as banks feared that if they denied applicants loans, competitors could advance the loans anyway. Arrangement fees were also tremendously reduced and in some cases even canceled. The desire to make loan packages attractive made banks reduce these fees to beat their competition on customers. Further, they employed more people to sell their loans and mortgages.

Serious negative effects followed these activities almost immediately. Those who took loans began defaulting, many small and medium businesses crashed with funds pumped into them and banks started experiencing liquidity problems. Interbank funding dropped, as banks were not sure of how prepared their competitors were to remedy the emerging crisis. Then came the full-blown crisis, and with it, any banks went under. Institutions that survived the scare had to change policies and strategies.

Today, however, regulations set by the government requiring banks to comply with tougher guidelines on liquidity are being felt heavily by SMEs. According to Hurley (2010), small firms “…bear the brunt of regulation forcing banks to meet tougher capital and liquidity requirements.” Below is the analysis of changes witnessed in the financial sector lending requirements after the crisis.

Rejection rates

According to Fraser (2012, p. 5), the level of rejecting loan applicants was lower before 2007-2008. However, after the crisis, the rejection rate is higher even for those small businesses with risk levels initially considered tolerable before the crisis. It is no longer business as usual for banks. In this process, however, the small and medium business owners face rejections, thereby denying them the much-needed funds to expand their operations. It is also ironic that banks have increased lending to businesses, but SME’s are literally starved of cash.

Margins

Marginal requirements were higher during the crisis, whereas during the periods when there were no financial threats, the margins were quite low. For instance, the period 2003-2006 was characterized by very low margins. In fact, some economists have argued that the period was characterized by the lowest marginal requirements in decades.

Arrangement fees

Before the crisis, arrangement fees were lowered to attract more loan intake. However, during the crisis, arrangement fees were very high to sieve only highly qualified applicants. This ensured that those who applied and consequently got loans were those who were highly qualified and capable of repayments.

Collateral

Collateral was seriously lowered before the 2008/2009 period to attract loan applications. However, in the period 2001-2005 small businesses were required to provide collateral to gain access to financial services. After the crisis, businesses with the same level of risk are required to provide collateral for any financing. This is also an indication of drastic policy changes, as those who could have qualified for loans in years preceding 2008/2009 are now considered unqualified for the same.

Collateral ratio

Small businesses that applied for loans during the crisis were required to provide collateral with a higher value as compared to the loan they wanted. Before the crisis, collateral required as a proportion of loans applied for was lower.

These policy changes have led to a diminishing amount of money available for SMEs, which led to the signing of an agreement involving four established banks Barclays, HSBC, LBG, and RBS, to advance loans to SMEs at affordable rates and more easily. According to the agreement, the banks are committed to assisting SMEs with their balance sheet equations to enable them to attract more loans. They are also working closely with alternative lending firms to assist collateral deficient SMEs (Goff 2012).

The comparison and contrast the last five years balance sheet and Income statement between Barclays and HSBC groups

Barclays PLC balance sheet attached in Appendix 1 reveals varied results for the five years running 2007-2011. These results are an indication of the company’s policy changes. Since the banks pursue different economic decisions they consider favorable to them, there must be differences in their operations and end-of-year results. Provided in Appendix 2 is the HSBC group’s balance sheet. It will also be used to provide information on how the bank’s management has been making operation decisions, advancing funds to borrowers, generating revenues, and meeting its financial obligations. In brief, the balance sheets of the two companies provide a lot of information regarding the decisions, strategic and operational, adopted by the top management of the two financial institutions. Knowing the effects of the managements’ decisions is only possible by using balance sheet and income statement results. Below is a discussion and analysis of the various components of the two firms’ balance sheet and income statement for the last 5 years.

Balance sheets analysis

Information obtained from a balance sheet is of great importance to shareholders since it indicates the financial strength of a company. The information, together with the cash flow statement and P & L, indicates the performance, strength, and profitability of a firm in a given period. In analyzing the balance sheet of the two companies, important metrics will be used to establish both companies’ strengths and stability. These metrics will be used to determine how the two firms use their assets to generate wealth, their ability to pay their debts, and liquidity. As such, leverage, current assets ratios, and quick assets ratios, will be analyzed.

Gearing/ Leverage

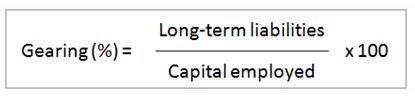

This ratio focuses on a firm’s financial structure. It shows the proportion of a firm’s total finance financed through debt relative to that provided by shareholders’ equity capital. Its results can also indicate the long-term liquidity of a firm. Gearing is calculated as,

Table 1: Barclays PLC Gearing

Barclays PLC is highly geared. This indicates that the company has very high fixed charge capital. However, this value has been reducing, which is an indication that the company is now opting for equity financing as opposed to debt financing. This is evidenced in a reduction from 57.16% in 2008, to 50.75% in 2009, 49.34% in 2010, and 46.81% in 2011.

Table 2: HSBC Holdings PLC Gearing

The capital gearing of HSBC Holdings is significantly lower than that of Barclays PLC. In the latest annual reports, the gearing of HSBC Holdings was 24.85% in 2011 as opposed to 46.81% posted by Barclays PLC during the same period. This is almost half the gearing posted by Barclays. This means that Barclays’ capital structure is significantly dependent on borrowed funds as opposed to equity finance; whereas HSBC Holdings, though financed by debt capital, debt is low and safe for the bank’s operations. The two institutions have, however, shown a decreasing trend in their gearing ratio. For instance, HSBC Holdings PLC recorded a gearing of 46.68% in 2009, the highest in a decade, which later dropped to 26.34%, and dropped further to 24.85% in 2011. This means that they are pursuing equity capital to finance most of their operations instead of debt. The high gearing levels in 2008/2009 can also be attributed to high loan failures in both institutions.

Liquidity

Investors prefer investing in assets that can easily be converted to cash. This makes it easier for them to get their money out of the investment easily in case of need. Therefore, the more liquid a firm’s assets are, the likelier it is for investors to invest in the firm and vice versa. To establish the liquidity level of a firm, two ratios are analyzed current ratio and quick ratio.

Quick Ratio

This ratio is an indicator of a firm’s short-term liquidity. It gauges a firm’s financial ability to pay its short-term financial obligations using its available liquid assets. When a firm’s quick ratio is high, it is considered to be in a good financial position. However, a firm with a low quick ratio is considered unfavorable to invest in because of its inability to pay off its financial obligations especially short term.

Current Ratio

The ratio measures a firm’s financial ability to meet its short-term financial obligations by using its assets (short-term). A higher value is an indication of the ability to pay short-term obligations easily. Usually, any ratio below 1 is considered unfavorable and assigned to the inability to meet short-term obligations.

Earnings per share

From the companies’ income statement, earnings per share can be found. This value shows what inventors have been able to earn from their invested money and, hence very important to potential and existing clients. Firms with high earnings per share attract more investors and vice versa.

The nature of balance sheet assets and liabilities also signifies a lot. The company’s loan structure, for instance, has fluctuated significantly over the period. Just before the financial crisis, the company issued consumer, private, and SME loans to the tune of 173.9 Billion. This value peaked in 2008 to hit 188.47 Billion. However, after the crisis, the value declined to 25.1 Billion. During the same period, HSBC’s loans to these groups showed a similar trend. The bank advanced 116.43 Billion for the category in 2007, 136.94 Billion in 2008, which dropped to 107.46 Billion in 2009, further to 100.05 Billion in 2010, and significantly to 73.78 Billion in 2011. Evidently, the measures have affected loan advancement to households and SMEs. On the other side, mortgage loans have shown a steady increase, an indication that the firms are shifting to issue their excess funds for mortgages. For instance, HSBC funded mortgages to a tune of 135.17 Billion in 2007, 169.25 Billion, 2008, 161.42 Billion in 2010, 171.61 in 2010, and 179.5 Billion in 2011(MarketWatch).

The two firms have shown contrasting trends in terms of debts. HSBC has been reducing its debt level over the last five years. In 2007, its debts stood at 214.43 Billion, which increased to 253.52 in 2008, after which it has been on a steady decline registering 201.93 in 2009, 201.54 in 2010, and 195.98 in 2011. Barclay’s debts, on the other hand, have been on the rise. In 2007, its debts stood at 400.23 Billion, which increased to 481.98 in 2008, before peaking at 490.04 Billion (Appendix 2).

From the balance sheet, we can also establish that the two banks have different asset and liability components. Barclay’s, assets have shown distinct behavior between the period 2008-2009, and the years immediately after. Intangible assets that fluctuated almost freely majorly affected the company’s total assets. In 2007, its total assets, in dollars, were 1.18T, which later increased to 2.052T in 2008. However, 2009 saw a significant decline of 0.674T to a record 1.378T. HSBC has shown a slightly different trend in its asset trend. In 2007, its assets stood at 1.18T, which dropped to 1.76 in 2008, 1.46T in 2009, before showing a slight improvement to attain 1.57T in 2010 and staying on the recovery track by posting 1.64T in 2011.

Assorted Average Ratios

From the two companies’ balance sheets and income statement postings over the last five years, many ratios can be calculated.

Table 3: 5-Year Averages for Barclays and HSBC Holdings

For the five-year period shown in table 3, the two firms have posted mixed results. For the period, the return on invested capital for Barclays has averaged 4.4%, while that of HSBC is 3.5%. This shows that for every dollar invested in Barclays by shareholders, the company has been able to generate an income of 4.4%. This is considered favorable. A higher rate of return on investment is a sign of good performance and therefore, using this matrix, Barclays is more attractive.

Return on assets (ROA), on the other hand, favors HSBC. Whereas HSBCs average for the five years is 0.5%, Barclays’ is as low as 0.4%. This shows that for all the assets HSBC has under its acumen, it generates 0.5% of its value in real income. Barclays’ ability to use its assets to generate income is, however, lower. ROA is an efficiency ratio and therefore, HSBC, using the ratio, can be considered more efficient in using its assets.

The debt to equity ratio is an equally important ratio. From the five-year averages, Barclays has 1.96 debts to equity ratio. This shows that for every invested amount, the bank uses 1.96 borrowed funds. HSBC, on the other hand, uses only 1.69. From these values, it is evident that Barclays funds most of its operations and investments through borrowing. This is not good as the firm may default and be declared bankrupt or overtaken by investors in a hostile manner.

Nothing matters to investors than profits. Investors will only invest their funds in companies that have shown or demonstrated the ability to make profits. A firm may earn a lot of revenue but still end up with little profits or even losses. This is where net profit margin comes in; it shows the margin of a firm’s profits from its earnings. Barclay’s average margin for the five-year period is 3.7% while that of HSBC is 12%. In this case, HSBC has posted impressive results as compared to Barclays. What this means is that HSBC has been able to convert most of its earnings into profits than Barclays does, that is, for any amount of revenue generated by the two firms, a higher percentage of HSBC’s earnings is profits. Barclays, on the other hand, posts a lower percentage of profits from its total annual revenues.

Barclays’ income statement also reveals varying provisions for loan expenses.

Annually, the bank sets aside an amount of money to compensate for bad loans. In 2007, the amount was $8.58B. In 2008, the figure increased to 13.16B, in 2009, 15.98B, before declining to 8.78B in 2010 and 7.18B in 2011. From this trend, it is evident that the 2008/2009 financial crisis affected the bank’s loan repayment as it used the highest amount of money to cover up for bad loans.

Description of the effects of the following on the expected performance of one of the above commercial banks

Regulations requiring the bank to increase its risk-based capital

Regulations requiring banks to retain a certain fixed amount of capital to offset market turbulences, if any, have been exercised for many years. However, in 1988, the risk-based capital standards were introduced following the recommendations of the Basel Committee. This regulation requires banks to hold not just a fixed amount of capital like before, but to do so about its perceived risk level. As such, it links the company’s reserved capital to weighted risks in its portfolio to avert failures arising from taking risky ventures with the little capital reserve that cannot remedy any eventualities. Banks had found a way around existing laws, thereby taking very risky ventures by replacing their share-based capital. According to Mehran, Morrison & Shapiro (2011, p. 16), “In replacing their share-based capital with arguably weaker forms of capital, banks leave themselves open to severe losses in future crisis situations.” These practices called for stricter regulations if the public and other investors were to be adequately protected from risky and careless practices by bank managers. This regulation has changed the way banks operate. However, it is claimed that its effect is minimal on financial institutions that command huge capital. Regardless of the capital base on a financial institution, the regulation’s effect has made operations not like they were before.

Government regulations that lead to escalated risk-based capital could result in numerous challenges to Barclay PLC and its customers. First, as the company is required to save more money to counter risky investments, its level of disposable capital is reduced. This means that the bank will have less money to issue to its clients in terms of loans and overdrafts. This situation could have adverse effects especially when loan applicants are many. With many applicants, the bank could increase the lending rate, thereby making loans expensive to many people and small and medium-sized businesses.

For an established bank like Barclays PLC, it is possible that the firm could take to riskier activities since it has the capital it needs to cushion it from any market risks that may arise. Considering the weaknesses of the regulation, the bank could beat them and venture into risky investments, which even though could promise high return, their failure could lead to the bank’s collapse, consequently leading to investors’ losses.

Increasing risk-based capital also attracts many challenges arising from a reduction in financing. One of the challenges that could arise from reduced financing is a possible rise in mortgages. This could make home acquisition cumbersome for first-time homeowners and thousands of people in middle-class income quarters. The effects of which cannot be overstated. Consequently, home sales could drop, which could cause massive job losses, and loss of income for thousands of families involved in construction and lumbering. When families lose income, they become liable for government assistance, thereby increasing the government’s burden, hence dragging the economy downwards.

Barclays PLC trades on the stock market. The stock market is always sensitive to any activity or decisions that may be seen to affect a firm’s position or profitability (Tambakis 2006, p. 15). Many could view increasing risk-based capital to affect the company’s income negatively; hence, its stock prices may decline, leading to a decline in share capital and ultimately dividends. The action may also force the bank to change the risk distribution of its principal assets. Additionally, the bank may reduce or cut funding to some of its programs to its disadvantage and that of its potential and existing customers. Finally, yet importantly, it is rational and expected of the bank to respond by increasing the charges of its services and activities. This will affect both customers and the bank, resulting in reduced income.

An increase in balance sheet liquidity

Increased balance sheet liquidity for Barclays PLC could pose numerous challenges for the bank. In the banking sector, liquidity is a chief concern (Wei and Tong 2009, p. 3). Sufficient liquid assets can help a firm pay off checks presented by businesses, give borrowers such as credit users funds to meet their financial needs, and to pay the bank’s recurrent bills. The need for liquid assets is majorly for meeting ‘on demand’ cash requirements. However, the main problem banks face in setting aside liquid assets to meet these ‘on demand’ cash requirements is an estimation of how much money can be needed at a time due to the unpredictability of clients’ cash demand; in amounts and timing.

Without sufficient liquid assets, Barclays could encounter off-balance sheet risks. These risks include Letters of credit and loan commitment failures. Letters of credit play a significant role in international trade. When an exporter sends goods to an importer, banks give the assurance that the exporter will be paid by issuing a letter of credit. In this regard, banks can only avoid a crisis by creating sufficient funds to pay the importer his/her cash on demand. However, without sufficient liquid assets, a crisis may arise. Loan credits are also issued on demand, and since banks cannot predict when the amount will be demanded, preparedness is crucial. Avoiding off-balance-sheet risks requires sound asset management practices. This will avert any risks associated with insufficient liquid assets.

The need for liquid assets by banks is evident. However, what is the risks associated with holding excess liquid assets or increasing liquid asset levels? Whereas a shortage of sufficient liquidity is a strong indication of an imminent failure in the banking sector, increasing liquidity could reduce a firm’s income from the held liquid assets (Thismatter). Liquid assets attract funds when in the hand of clients. Holding excess liquid assets is against the principle of maximizing shareholders’ wealth. Therefore, the bank should hold only sufficient liquid assets to meet its customers’ demand to avoid experiencing a bank run (Mankiw 2012, p. 452). Sufficient funds, in this case, are amounts that will satisfy their clients’ withdrawal and overdraft needs. This will ensure that the bank’s operations remain on track and its liquid assets are in the hands of clients earning its interests.

Given the risks of excess liquid assets, what options are available for Barclays PLC to manage its liquid assets? First, the bank can create reserves in a vault or with the Central Bank. However, the shortfall of this decision is that the liquid assets saved with the central bank earn no interest or very little interest. Another available option is to create an account with a competing bank such as HSBC for saving excess liquid assets. The best option, however, is buying British treasuries.

References

Dullien, S, Kotte, J, Marquez, A, & Priewe, J 2010, The Financial and Economic Crisis of 2008-2009 and Developing Countries, United Nations. Web.

Fraser, S 2012, The Impact of the Financial Crisis on Bank Lending to SMEs, Department for Business Innovation & Skills, London.

Goff, S 2012, UK banks eye alternative lending for SMEs. Web.

Hardie, I, & Maxfield, S 2010, What does the global financial crisis tell us about Anglo-Saxon financial capitalism? Edinburgh. Web.

House of Commons Treasury Committee, 2009, Banking Crisis: dealing with the failure of the UK banks, House of Commons, London.

Hurley, J 2012, SME lending warning over shadow banking. Web.

Machlup, F 1940, The stock market, credit and capital formation, Macmillan, New York.

Mankiw, N 2012, Essentials of economics, 6th edn, South-Western Cengage Learning, Australia.

MarketWatch, n.d., BCS Annual Balance Sheet. Web.

MarketWatch, n.d., HBC Annual Balance Sheet. Web.

Mehran, H, Morrison, A, & Shapiro, J 2011, Corporate Governance and Banks: What Have We Learned from the Financial Crisis? Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Web.

Tambakis, D 2006, Endogenous Market Turbulence, Cambridge. Web.

Thismatter.com. n.d., Bank Risks. thisMatter.com: Fundamental Tutorials about Consumer Finance, Investments, and Economics. Web.

Wei, S & Hui, T 2009, The Composition Matters: Capital Inflows and Liquidity Crunch during a Global Economic Crisis, Issues 2009-2164, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Wikinvest. n.d., Quick ratio for Barclays. Barclays BCS. Web.