Background of the Study

In recent years, a global surge in the number of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occasioned by motor vehicle accidents have been witnessed in the United States of America. PTSD generally refers to an anxiety disorder witnessed in people who have undergone through a series of trauma, through seeing or experiencing events that had the capacity to cause serious harm or even death. The major symptoms include nightmares, uncontrolled worry and increased angry outbursts, and the condition is treatable through psychotherapy and medications (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009). PTSD brought about by motor vehicle accidents has gained prominence due to the propensity of its occurrence for all accident victims regardless of whether they sustained injuries or not.

Problem Statement

PTSD is usually aggravated if proper screening fails at first contact between the victim and the medical practitioners. An increased number of chronic PTSD occasioned by motor vehicle accidents has become a big problem mainly due to ineffectiveness in the screening for conditions such as anxiety and stress in accident victims.

Conceptual Framework

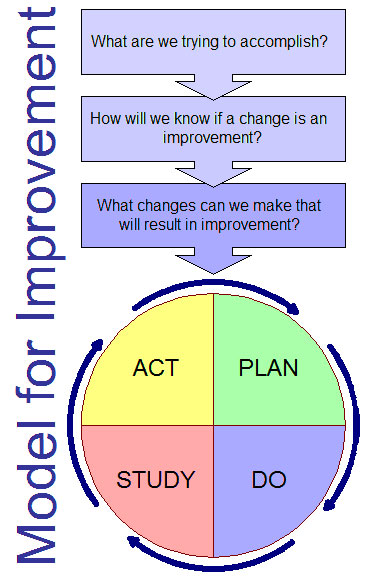

The conceptual framework describing this project is a model for improvement. The aim of the model is to improve stress assessment in post MVA victims. Through the introduction of a number of changes to the stress assessment approaches, stress levels can be monitored at an early stage so as to minimize incidences of PTSD. Incorporation of a stress thermometer in the early stage of stress assessment helps in tracking the stressors thereby by tackling these stressors, the changes introduced above may lead to improvements in stress assessment. This model has four components (planning, doing, studying and, acting). Firstly, we start by planning for the incorporation of the stress thermometer in stress assessment and collection of data (Shawn et al., p.83). This also entails the formulation/ reviewing of objectives, followed by the predictions or questions that need to be addressed by the model, in addition to a plan to carry out the cycle (that is, who, what, where and when), finally the plan for data collection is laid down. This will aid in the definition of the project, assessment of the current situation and analyzing how the victims react to stressful situations and thus the cause of chronic PTSD.

Secondly, the doing component is comprised of three tasks. We start by carrying out the plan, followed by documentation of observations made, and finally recording of the relevant data which sets the beginning of data analysis. In this case, stress tracking charts can be employed in recording and documenting the locations, situations and activities that can be regarded by the victims as being stressful. This charts help in creating worksheets that can be employed by the health providers in helping the victim to recognize the symptoms of personal stress and therefore increasing self awareness and decreased incidences of PTSD (Shawn et al., p.84).This will also help in the setting up of an appropriate methodology and recording of the observed data.

Thirdly, the study will entail the analysis of data through comparing the collected data, followed by a comparison of the results obtained from the study and other previous studies. The comparison will help us to verify the hypothesis or refute them relative to the results of the study.

Fourthly, acting looks into the changes that needs to be made and, whether to proceed to the next cycle (that is) planning a continuous improvement approach after the hypothesis has been accepted. According to the results we will be able to ascertain the necessary changes that were proposed and set the way forward in the improvement approach.

This model is appropriate for this project because it helps the planner to establish the current situation, and at the same time asses the prospective improvements that may change the situation as it is. From the study that will be conducted, data will be recorded for the assessment of the changes that needs to be implemented and at what stages. Again, comparison is made easily between the current study and the expectations that are predicted as the hypothesis/ objectives of the project. Finally, the model helps in setting a continuous path for the continuation of the cycle, which continuously improves the situation (SA Health Manager Wiki, 2007, par.28).

Background

Awareness levels on the psychological reactions that occur after involvement in accidents have continually increased in the past few years (O’ Donnell, 2003, p. 583). Several studies carried out have indicated that the psychiatry incidences and symptoms occasioned by car accidents have the propensity of plummeting after the first month. However, persistence of the symptoms beyond the first two or three months likely leads to the development of chronic PTSD. According to NIMH (2009), about 3.6 of the adults in the United States between the ages of 18 to 54 experience episodes of PTSD annually, with war veterans and car accidents victims forming the largest proportion. More than 5.2 million people suffer from the posttraumatic distress disorder with new cases reported to approximate about 9 million each year (NIMH, 2009). The number of women affected and the risk of suffering was more than thrice that of men in the United States.

Prospective studies have indicated that psychological factors play a major role in influencing the persistence of the PTSD at two or three years. Negative interpretations particularly of intrusions and rumination cause the persistence of PTSD in accidents (Harvey & Bryant, 1998, p.234). More importantly, gender, perceived threat, legal process, acute health and financial difficulties and the length of the hospital admission have all contributed to the persistence of PTSD (Mayou, Ehlers & Byrant, 2002, p.665). According to Fullerton et al. (2001, p.1485), women have greater chances of developing PTSD due to the propensity that they experience more intense feelings and higher risk of achieving the overall avoidance criterion and to a larger extent the overall arousal criterion. This is due to the increased risk of sustaining heightened sensitivity in terms of contextual and the common memory linked arousal that has the capability of sustaining high arousal states thereby leading to chronic avoidance (Fullerton et al (2001, p.1485). The understanding of the statistics and predisposing factors is imperative in the development of psychological assessment and aids in the psychotherapeutic treatment (Hepp et al., 2008, p.373).

Conclusion

The study is significant since it provides crucial information that is imperative in designing mitigation, prevention and control measures aimed at reducing the occurrence of chronic PTSD in car accident victims, taking into consideration the ever-increasing incidences.

Reference List

Fullerton, C., Ursano, R., Epstein, R., Crowley, B., Vance, K., Kao, T., Dougall, A. & Baum, A. (2001). Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(9), 1486-91.

Harvey, A. & Bryant, R. (1998). The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective evaluation of motor vehicle accident survivors. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 66(3), 507-12.

Hepp,U. Moergeli, F., Buchi, S., Bruchhaus-Steinert, H., Kraemer, B., Sensky, T. & Schnyder, U. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder in serious accidental injury: 3-year follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(5):376-83.

Mayou, R., Ehlers, A. & Bryant, R. (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents: 3-year follow-up of a prospective longitudinal study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(6), 665-675.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2009). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Web.

O’Donnell, M,, Creamer, M,, Bryant, R., Schnyder, U. & Shalev, A. (2003). Posttraumatic disorders following injury: an empirical and methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 587 –603.

SA Health Manager Wiki. (2007). Model for Improvement. Web.

Shawn, H. and Myles, B. S. (2007). The comprehensive Autism planning system (CAPS) for individuals with Asperger Syndrome, Autism and related disabilities: integrating best practices throughout the student’s day. Kansas: Autism Asperger Pub. Co.