Introduction

Income inequality based on gender is the dissimilarity between male and female earnings usually expressed in part by male earnings (Miller, 2014). In other scales, it has been fondly described as the average divide between men and women, in terms of hourly earnings. These are also seen to be in popular practice because men generally go for high demanding jobs, which attract high remuneration. On the other hand, women tend to evade high paying jobs. Moreover, other scholars view this tendency as a representation of the amount of work experience, as well as breaks in employments, which in most cases go against women’s competitiveness (Miller, 2014).

Debates on income inequality continue to be a key issue in most circles. So debatable has the topic to the point of seeking whether both women and men should make specific choices due to socio-economic pressures. The most amiable standpoint from which to view the inequalities in the income structure between the genders is to approach it from the median wages that men and women take home at the end of the month. According to Miller (2014), this model of comparison between men and women is somewhat limited or outright illogical given that both genders exhibit totally different characteristics, which eventually shape the scope of their assignment and affect their pay as well. Men in their nature tend to be engaged in fields that offer the utmost average pay, and have a culture of working more hours per day (Sullivan, Sheffrin, & Perez, 2013).

Women, on the other hand, have a tendency of working the least hours, as most have to leave work places much earlier to attend to various household chores, thereby delimiting their chances for higher pay. It is also not lost, however, that women record the highest frequency for absenteeism and experiences many breaks in employment.

Income Inequality Case

Given the differences that characterize men and women in their individual capacities, it would be imprudent to explore the differences that inform the various career choices that men and women have to make. The averaging wages of rewarding both men and women at work have been misrepresentative ways used to inform public policy without necessarily giving an explanation to all that appertains to this commonplace income inequality (Hill, 2014).

According to Miller (2014), observable differences exist between men and women, thus affecting their delivery at work; this accounts for the difference of income inequality. Available statistical analysis that explores this situation often provides variables that account for these inequalities (Hill, 2014). Much of the work done by researchers in this field show that gender inequality is at the forefront in shaping the income inequality while tilting these advantage to men. Many researchers, as Miller (2014) notes, have attested to the fact that the difference that exists between men and women when it comes to making career choices is in part because of the inequalities or social pressures that the society dictates on the female gender. As women continue to be discouraged from lucrative jobs, men, on the other hand, continue to be discouraged from committing to choices at work, especially by way of prioritizing on job satisfaction against pay.

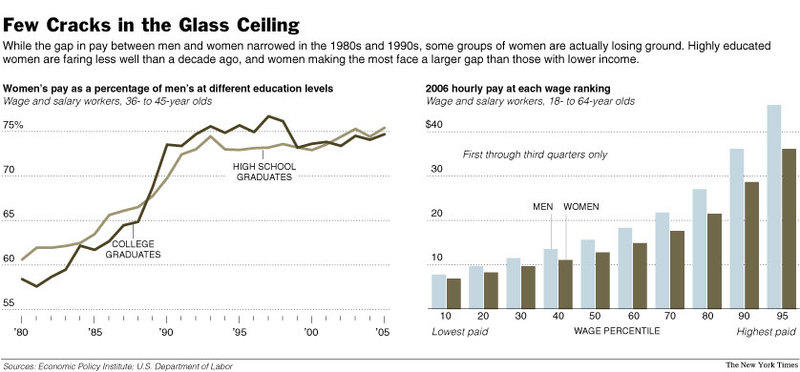

The wholesome fact about gender-based income inequality addresses these issues succinctly by offering archetypical case scenarios within the report entailed in the Gender Pay Gap (GPP). The report explores the gender pay gap in the service sector in the US (Hill, 2014). Under these considerations, the report explains how the gender factor affects women of all walks, all ages, education levels yet no much can be done to shut this gap (Worstall, 2014).

Equal Pay for Equal Work

According to The Gender Wage Gap and a Solution to Income Inequality (2014), in the event that the leave has to be granted to a woman, the same should be extended to their spouses. The author opines that it is high time the term maternity leave be eradicated to stop the stigmatization of women at the workplace; the author opines that in place of maternity leave, a phrase like parental leave should be effected so that both the father and the mother of the unborn can be treated equally. Over the past few weeks, debate has been heightened in Washington with President Obama categorically calling to attention what he referred to as an embarrassment in the US – the fact that the American womenfolk continue to earn just below what their male counterparts were doing in most service sectors in America was the main theme (Shear & Lowrey, 2014).

According to Shear and Lowrey (2014), women, on average, make a paltry 76 cents against a dollar earned by men. According to Kollipara (2014), this case scenario means that for the women in America to rival their male counterparts, they will have to work an extra 60 days to match the already tilted women-biased economy. New empirical study also shows that technological changes have contributed largely to the current increase in income disparity among full-time workers. The impact on income disparity also could be a mirror reflection that changes in technology might shape the demand for medium skilled income earners by reducing their demand in the labor market; statistics has shown that women have scored lowly in this area. In addition, in a scenario where there are shifts in demand and labor fails to reciprocate, it is evident that technological progresses reduce the earning of medium-skilled personnel (Sullivan et al., 2013).

In trying to achieve the ideals of gender equality, women have to be trained in production, management, technological improvements, and systems assuring safety and quality in manufacturing in order to augment their pay.

Gender Pay Gaps

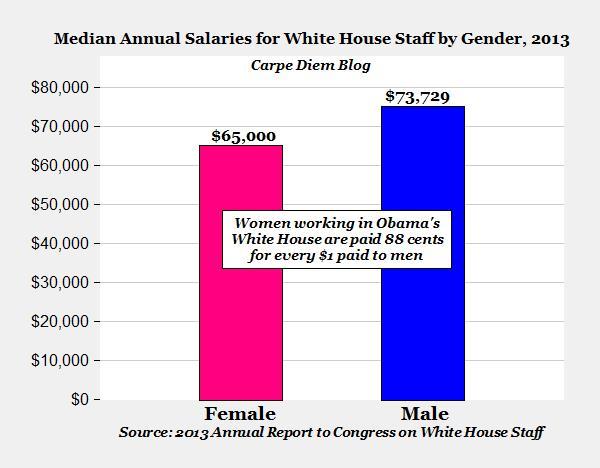

Recently, President Obama made a shockwave across America when he hatched a plan aimed at cutting down the wage gap between men and women (Perry, 2014). Proponents of these developments note that the idea of ordering the federal contractors to give their employees the information regarding the salary structure would be a positive aimed at solving the pay gap, as many workers would be willing to share their experiences, thereby making it easy to have a unified workforce (Kollipara, 2014).

According to Kollipara (2014), the presidential decree to ensure shared salary information is part of the broader effort by the Obama administration to address the numerous challenges women face in the service sector in America. The senate has further sounded this call to decency in the American service sector as the Democrats continue to push for a popular vote on the PayCheck Fairness Act (Kollipara, 2014). Accordingly, these developments are part of a larger scheme that aims to fast track the reforms in the United States’ service sector.

The Obama administration has continued to push for the application of this lease on federal contractors across America (Perry, 2014). In order to realize gender impartiality, it is imperative to build a society in which both women and men share all things equally in the distribution of power and influence in order to have equal access to decent work, health, and education and above all an equal pay as their male counterparts. How the society is going to approach these challenges is essentially, what will close down gender-based income disparities (Kollipara, 2014).

Women Education

Despite the tremendous expansion of educational opportunities globally, women not only in America, but also in various developing countries continue to receive compromised schooling as compared to men (Miller, 2014). Yet there is fascinating evidence that girl child education promotes the welfare of the society in general. A living example is the strong link between a woman’s education, subsequent employment, and income. It is no doubt that well-educated women bear few children, who have higher chances of surviving infancy, thereby assuming a healthy life, with the likelihood of acquiring better education, securing a better job and a better pay. Whenever women are deprived of education, families, children, as well as the societies suffer the consequences, as this replicates in their salary scales (Miller, 2014).

Whenever women are adequately educated, everyone in the vast society benefit. Why then do womenfolk in the American society continue to lag behind men in terms of payments? Our concern at the moment should begin to address this puzzle by examining how educational decisions are made across the board. This should be done by exploring the costs and benefits that determine how much the government invest in educating the girl child. A subsidized fee in secondary schooling and college education for girls can increase their future employability, by about 10% to 20%. In addition, evidence demonstrations that those resources that are under the watch of women go into household consumption that benefits children and the society by large. Previously we have witnessed situations where our women folk have excelled exceedingly if they are given a chance to partake similar opportunities that men hold so passionately.

In 2012, for example, over 80 percent of the new loaning and grants embraced gender in their project operations and received tremendous positivity – a proof that women have come of age, and can always put chances into good use whenever considered (Miller, 2014).

Entrepreneurship

The participation of women in the productive sectors, especially as entrepreneurs, can be nurtured through policy assimilation, capacity building, and institutional support amongst other initiatives (Worstall, 2014). It is undeniably that in the current society, poverty has often been synonymous with women. Women and girls, according to United Nations, constitute three-fifths of the poor population globally; their poverty rating is worse than that of men because of clear gender disparities in various areas including remuneration aspects. Women empowerment response seeks to foster active participation of women in income generating activities, with a robust focus on entrepreneurship. This effort should aim at delivering women to a sustained income and equitable salary to their male counterparts in the service sectors.

According to Hatt (2014), this can be achieved amicably through enterprise development programs that address the inequalities faced by women at various workplaces. Enhancing women’s access to credit facilities, business financing, as well as the capacity to be accorded equitable salary pay, can adequately unlock the untapped human capital in women. Research indicates that global progress in achieving gender equality is lagging behind because most women are technically locked out on free enterprise (Sullivan et al., 2013).

Conclusion

Empowering women is perhaps one of the most frequently cited social objectives in achieving gender equality. The impact of gender equality on women empowerment, however, is equal to societal growth. It is clear that achieving gender-based income equality will not be feasible without closing the gap between women and men in terms of capacities, access to resources and opportunities, and reduced vulnerability to discrimination, especially in terms of job placement and payment scales. Gender-based income equality is a multi-faceted concept and an enduring process. Therefore, embracing it is in itself such a noble duty that all the service sectors in America must adopt.

As the definition of women empowerment indicates, the women empowerment process is a force to anticipate. Even though women empowerment is a complex initiative, it is a multi-dimensional process, which is expected to deliver humanity to economic freedom. A comprehensive intervention that embodies different domains of this process is essential in empowering women on a substantial scale.

References

Hatt, K. (2014). Why the New York Times ‘richest middle class’ title may not be all good news.

Hill, C. (2014). The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap (2014). Web.

Kollipara, P. (2014). Wonkbook: What you need to know about the gender pay gap. The Washington Post. Web.

Miller, C. (2014). Pay Gap Is Because of Gender, Not Jobs. The New York Times. Web.

Perry, M. J. (2014). Team Obama struggles to explain, defend the 12% gender pay gap at the White House, first reported here seven months ago. Web.

Shear, M. D., & Lowrey, A. (2014). As Obama Spotlights Gender Gap in Wages, His Own Payroll Draws Scrutiny. The New York Times. Web.

Sullivan, A., Sheffrin, S. M., & Perez, S. J. (2013). Economics: principles, applications, and tools (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. Web.

The Gender Wage Gap and a Solution to Income Inequality. (2014). Web.

Worstall, T. (2014). I Declare The Gender Pay Gap To Be A Truly Dead And Gone Issue. Forbes Magazine. Web.