Introduction

Indigenous peoples continue to experience greater rates of sickness and death, food insecurity, subpar living conditions, and poor mental health on a global scale. Communities responsible for their health, medical systems, and services are key to effective outcomes. These control discourses contain ideas such as indigenous participation, involvement in health programs, policy-making, economic restructuring, and culturally acceptable healthcare acknowledged as a political right. Without authority over healthcare, it is unclear what special viewpoints, passions, backgrounds, and settings are. Indigenous people contribute to their healthcare treatments and how they best shape the treatment they get for themselves and their families.

Increasing attention to the issues of persistent racism towards Indigenous peoples, inequality, the background of institutionalized healthcare, and a lack of knowledge of their distinctive life experiences are also discernible. Thus, the paper aims to investigate a certain feature, piece of law, or child welfare program, particularly service shortages or other relevant issue areas related to the course’s focus.

Child Welfare Policies

Categorizing Indigenous health and well-being is part of a larger conversation about decolonizing the medical system. Research and policy efforts domestically and abroad have centered on giving Indigenous governments control over the healthcare system. Repositioning expertise as part of decolonization means empowering Indigenous peoples to speak up for and participate in health efforts. In addition, there has to be a systematic change away from the currently dominating linear approach to health. Indigenous communities’ current knowledge emphasizes perspectives on health and illness that are more inclusive and comprehensive.

They try to align with traditional perspectives and recognize the full range of factors influencing wellness across life courses. It includes access to and participation in producing nutritious foods, activity level, spiritual appearance, and community empowerment, among numerous levels of human existence, such as social, political, and economic ones.

Discussions in the community about the fundamental problems with healthcare delivery and transformation initiatives in on-reserve populations with successfully created community-based primary care models gave rise to a focus on decolonization. The study program’s active First Nation participation and leadership provided insight into aspects of healthcare delivery that make up First Nation government (Carneiro, 2018). Ample consideration was given to neighborhood direction and interests, socioeconomic factors influencing health, integrative programming, folk medicines, and jurisdictional bridging in well-created, community-based healthcare models (Carneiro, 2018). Through their engagement and involvement, complicated and enduring problems appeared to be easily addressed.

Decolonization tackles the many reasons why medicine and Indigenous health results do not align and the source of enduring inequality itself. It is a process of reclaiming political, cultural, economic, and social independence, as well as the reinvention of positive identities at the individual, familial, communal, and national levels. Decolonization uses pre-colonial, “traditional” knowledge and practices to build on colonial legacies. Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples must actively participate in these endeavors. With its revolutionary potential, decolonization calls for the destruction of colonialism as the guiding paradigm for Canadian society in general and healthcare in particular.

However, First Nations leaders in Canada continue to strive for control over their social programs without guaranteeing that localized government will be recognized. Contrary to popular belief, the economic development of indigenous tribes on both sides of the frontier has not come at the price of maintaining their historical and cultural traditions (Zhao, 2021). Indian nations always use the riches they accumulate via economic growth to benefit their citizens. In addition, economic progress is linked to children using their native tongue at higher rates than their parents, suggesting that language is passed down through generations and that traditional cultural components are becoming more commonplace.

This can create a positive feedback loop where increased native language usage percentages signal better corporate performance. Tribes with more native language usage had better native tribal management of the forests. Tribal cohesiveness promotes superior economic performance and responsibility, which feeds the cycle of culture and economy (Zhao, 2021). On the other hand, the repression of cultural identity can have devastating effects beyond economic output or even cultural thriving. Youth suicide rates were higher among Canadian First Nations, with fewer cultural hubs, land claims, or independent control of their educational and medical facilities, according to key research published in the Journal of Experimental Psychiatry (Zhao, 2021). This association demonstrates the fundamental need for self-identity and group membership.

Seven Grandfather Teachings

An important indigenous story determines the principles of natives and their welfare about a creator who charged the seven Grandfather spirits with keeping a watchful eye over the Anishinaabe population. The Anishinaabe values needed to be transmitted; therefore, the Grandfathers dispatched a Messenger to earth to locate a representative (Seven grandfather teachings, 2021).

The Messenger looked in every direction before discovering a baby. The infant was to travel with the Messenger for seven years to comprehend the Anishinaabe way of life, as directed by the Seven Grandfathers. The infant, who was now a young boy, was given seven precepts by the Grandfathers once they returned: love, respect, courage, truth, honesty, modesty, and wisdom (Seven grandfather teachings, 2021). The Anishinaabe are instructed to live a decent life in peace and harmony by the Seven Grandfather teachings, a collection of key principles carried from one generation to the next.

Several Indigenous groups and communities have embraced the Seven Grandfather Teachings as a moral compass, and cultural cornerstone and communities have modified the teachings to fit their ideals. The same principles of moral regard for all living creatures are present in all teachings, regardless of where they originated. Since they are accessible and include the kinds of ideals that humanity may aim to live by, the Seven Grandfather Teachings are one of the Anishinaabe concepts that are almost universally accepted. They provide strategies for enhancing lives while residing in harmony and peace with the entire created order.

Importance of Indigenous Language

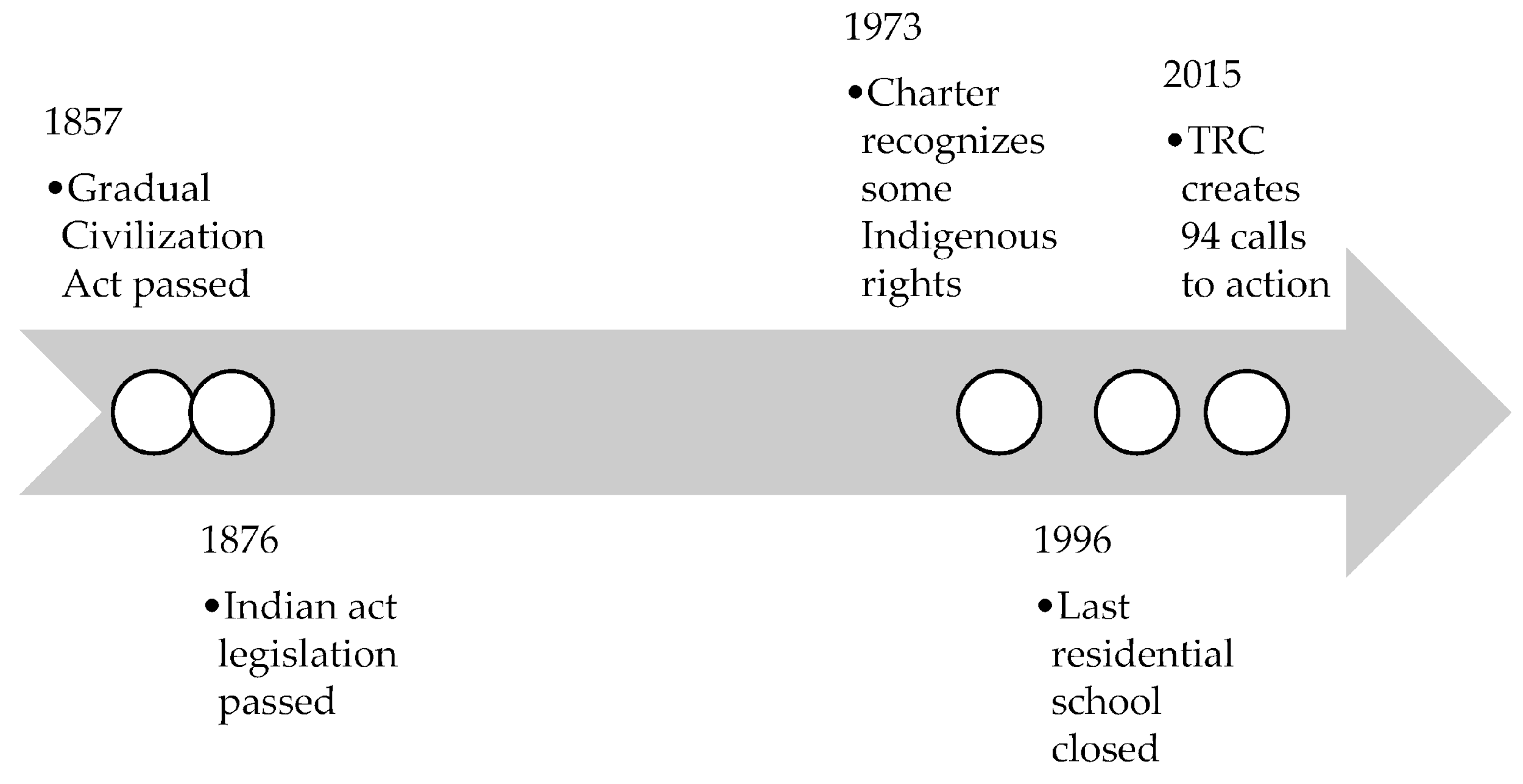

The disappearance of many native languages in Canada is a serious concern. While some languages are still alive and well, others have vanished entirely. In order to stop additional language loss, decisive action must be taken. Indigenous cultures and dialects have been attempted to be eradicated during Canada’s deplorable history of eradicating First Nations’ ways of existence through institutionalized techniques like residential schools. The Indigenous language and tradition suffered tremendously as a result of these attempts, which were not effective. Language loss harms the transmission of knowledge between generations in indigenous groups and jeopardizes individual identity. In addition, assimilation’s cumulative consequences have made it harder for Indigenous people to maintain good physical and mental health (Khawaja, 2021). However, it has been discovered that language reclamation enhances well-being and a sense of community.

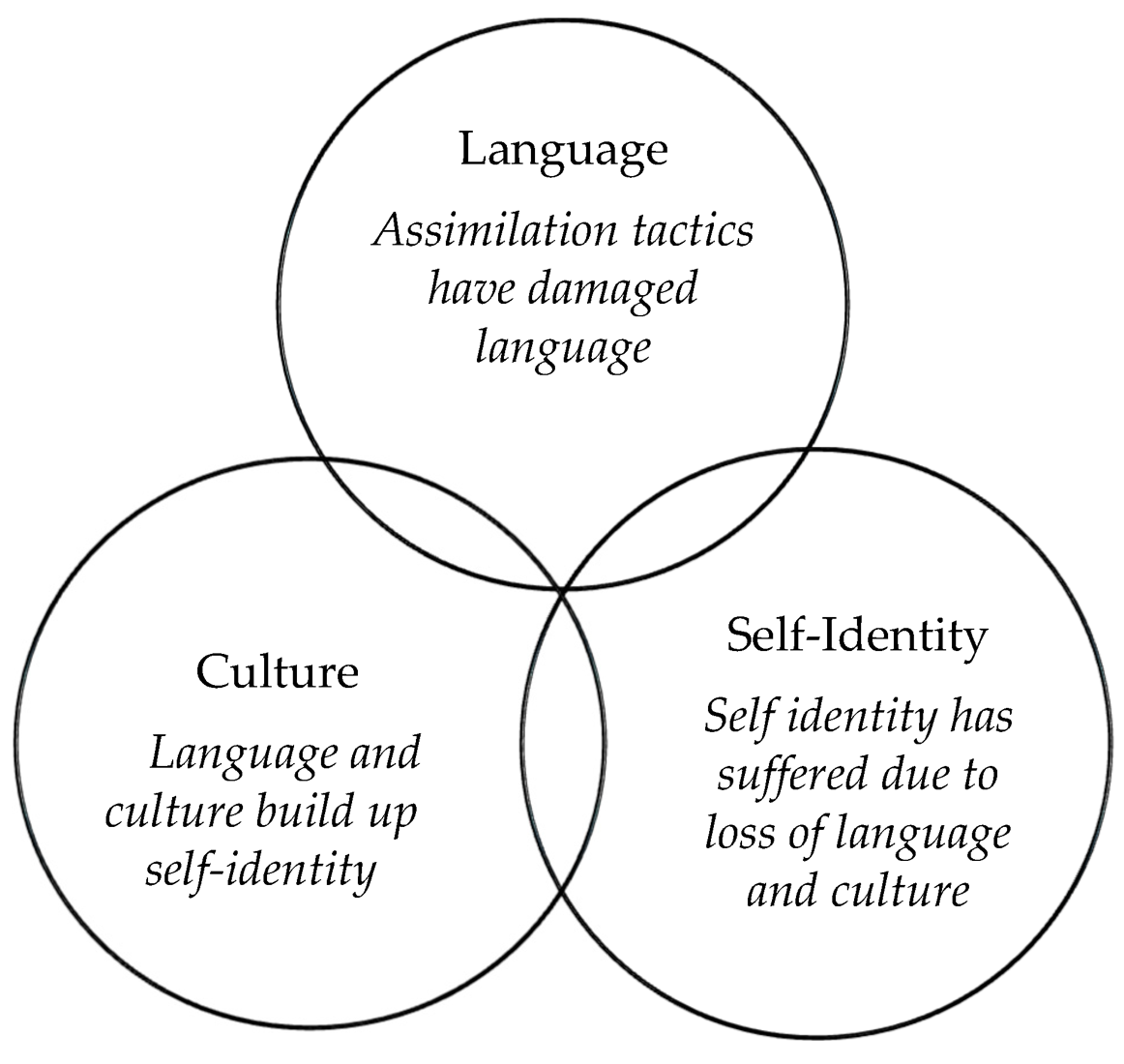

Many Indigenous cultures understand that the loss of a language results in the loss of a culture, which significantly influences a person’s sense of self-identity. Given the undeniable interdependence between language, cultural heritage, and society, the decline of any of these factors frequently results in the decline of all three (Khawaja, 2021). People who experience this are frequently caught between two cultures and feel lost when they cannot fit easily into either. Furthermore, for Indigenous groups, a strong sense of cultural identity is a key and significant psychosocial driver of health and well-being. In order to enhance the livelihoods of Indigenous people, the triangle of language, culture, identity, and self-identification must be developed.

Older generations still feel the effects of previous measures designed to eradicate language and culture. Although residential schools have been closed for more than twenty years, the effects of the institutions still influence older Indigenous individuals in numerous ways, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Khawaja, 2021). The trauma was delivered from parent to kid, so even people who did not personally witness the forceful integration may feel it later in life. Elders are the main users of Indigenous languages, and they frequently encourage new generations to learn their language (Khawaja, 2021).

Unfortunately, families were deprived of the chance to communicate more deeply across generations by utilizing their native languages due to residential schools. As a result of the pupils’ inability to speak their native tongues, linguistic barriers grew, and communities became more fractured as they began to lose inherited relationships with family members. For residential school kids, this resulted in unavoidable isolation even after they left this institution.

Supporting Indigenous communities while they recover from historical injustices is a duty shared by all of society. Particularly, significant institutions must take the lead in rehabilitation initiatives. As a result, colleges and governments should take the lead in revitalizing Canadian languages. Universities are a symbol of society’s ongoing learning and creativity, and they are frequently the first organizations to modify their operations in response to shifting social norms. Because of this, universities are the perfect places to encourage creativity and collaborative learning. Although students are unlikely to become fluent, post-secondary courses offer a chance to reconnect with one’s cultural roots and aid in the constructive conceptualization of one’s self. The government, which has long been the main culprit of heinous crimes against Indigenous people, also plays a significant part. In order to conserve endangered Indigenous languages, hurdles must be quickly recognized and removed at several levels.

The Role of Research Approaches

Indigenous populations continue to experience health inequities due to colonial processes and an inaccurate and insufficient collection of data about themselves. Researchers in colonized nations have advocated for an Indigenous-specific approach to epidemiology for the past 20 years (Hayward et al., 2021). This approach would acknowledge the limitations of Western epidemiological techniques, incorporate more Indigenous research methods and culture-participatory research techniques, build capacity by coaching more Indigenous medical experts, and support Indigenous self-determination (Hayward et al., 2021).

Indigenous epidemiology can take several different approaches, such as: adapting standards, like age standardization, to Indigenous populations in order to give their experiences the proper weight; carefully setting hiring targets and using effective hiring methods in order to meet numerical standards for stratification; serving as a bridge among Indigenous and Western order to achieve good results perspectives; and change and improve appropriate data collection tools.

Indigeous Family Services: Tikinagan

One example of the indigenous organization of child and family welfare is Tikinagan. The Chiefs established Tikinagan to uphold and build families, communities, and youth. The children are the communities’ future, and their communities and families must provide for them. As a result, a crucial component of Indigenous self-government is communal responsibility for child safety. Tikinagan Child and Family Services are one of the 53 Children’s Aid Societies in Ontario required to safeguard children by the Child, Youth, and Family Services Act (Governance, n.d.).

Workers must consult with Elders for their knowledge, direction, teachings, and wisdom in all aspects of service delivery. Tikinagan employees are obligated to cooperate with First Nations on any case managerial decisions since one of the model’s basic values is a responsibility to the First Nations. All situations involving the well-being of children involve First Nations, and they collaborate with Tikinagan to create service plans for families, placement choices, and care plans for children in foster care. Services are sensitive to cultural differences and supportive of enduring beliefs and traditions.

Welfare Reforms in Canada

Canadians have been shocked by the discovery that hundreds of native children are interred in grave sites at the locations of defunct residential schools. Demands for improvements to the nation’s child welfare system, where native children are disproportionately overrepresented, have also intensified. A native organization offering culture-based programs, child welfare officials should aim to provide indigenous families with the support they need to keep their children despite any difficulties they may experience.

After decades and decades of systems of residential schools and, subsequently, foster care tearing families apart, it is crucial that were create conditions in which families can stay together and study indigenous culture and language. However, only 3% of the inquiries the organization gets result in separating a child from their parent or legal caregiver (Goffin, 2021). When a kid is taken away, efforts are made to reunite them with other family members or community members.

The government must also address pervasive societal issues resulting in circumstances when children are taken away from their parents. Indigenous leaders cite high child poverty rates, above-average suicide rates, and persistent concerns with reservation housing and water facilities as the main problems. Since Prime Minister assumed office in 2015, the Liberal administration has moved to enhance support for indigenous kids (Goffin, 2021). Although it is not the end of the narrative, it moves a significant departure from the oppressive grip of the law and toward one that elevates preventative approaches.

Other subtle alterations are also occurring. At the grounds of the previous Marieval Indian Residential School, the Cowessess First Nation recently discovered some 750 unmarked graves (Goffin, 2021). It entered into a multimillion-dollar arrangement with the provincial and federal governments to grant the First Nation control over child welfare services, which will be shaped by its goals, values, and culture. Due to a new law established in 2019 affirms indigenous people’s ability to implement control over services to children and families in their communities, making that relationship feasible (Goffin, 2021). Due to the multigenerational trauma of residential schools, spousal violence, drug abuse, inadequate housing, and poverty are the main causes of indigenous children entering foster care.

Gaps in the Indigenous Welfare

There is fiscal discrimination against indigenous people since the accessibility of services and resources depends on whether a person lives on or off a reservation and whether the program is supported by the state or federal government. This is why the government should increase funding for Indigenous child welfare programs and align them with the needs-based funding principles of the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, including community wellness based on cultural values (Cordasco, 2022). In order to switch to the federal financing model, the province must ask for a bigger budget (Cordasco, 2022). Due to a patchwork of financial arrangements, the federal government completely finances Indigenous organizations that operate on reservations but does not fully fund those organizations if they carry out off-reserve service delivery under contract with a province.

Services given off-reserve are the province’s responsibility, but those offered on-reserve and not delivered by Indigenous organizations are partly funded by the federal government. Despite claims from service providers that the provincial system’s flaws are well-known, the state lacks the tools to assess it (Cordasco, 2022). The research advises the ministry to restructure its data collecting and administration systems to address its dysfunctional financial allocation system (Cordasco, 2022). These systems cannot monitor where and how funds are spent or if programs are reaching policy objectives. The government must first gather race-based statistics to comprehend the varied and increased requirements of the First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and urban Indigenous people it serves.

Conclusion

Overall, the broader discussion on decolonizing the medical system includes indigenous health and well-being. The secret to successful results lies in communities that have taken ownership of their healthcare, medical systems, and services. Without control over healthcare, it is unknown what unique perspectives, interests, histories, and environments exist. For Canadian society and the healthcare system, decolonization eradicates colonialism as the dominant paradigm. People from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous backgrounds must take an active role in these initiatives. The passing of information across generations is hampered by language loss. The cumulative effects of assimilation have made it more difficult for Indigenous people to maintain sound mental and physical health. The triangle of language, culture, and identity, as well as self-identification, must be fostered to improve Indigenous people’s lives.

References

Carneiro, S. (2018). Policy, poverty, and indigenous child welfare: Revisiting the sixties scoop (Doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University).

Cordasco, L. (2022). B.C.’s misaligned Indigenous child welfare system causes ‘fiscal discrimination’: report. Vancouver Sun. Web.

Goffin, P (2021). Why Canada is reforming indigenous foster care. BBC. Web.

Governance. (n.d.). Tikinagan Child & Family Services. Web.

Hayward, A., Wodtke, L., Craft, A., Robin, T., Smylie, J., McConkey, S.,… & Cidro, J. (2021). Addressing the need for indigenous and decolonized quantitative research methods in Canada. SSM-Population Health, 15, 100899. Web.

Khawaja, M. (2021). Consequences and remedies of Indigenous language loss in Canada. Societies, 11(3), 89. Web.

Seven grandfather teachings. (2021). Seven Generation Education Institute. Web.

Zhao, S. (2021). A progressive facade: comparing the U.S. and Canada’s treatment of indigenous peoples. Harvard Political Review. Web.