ESIA in Public Transportation

Developments in public transportation projects such as rapid mass transit as it is in the Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Project have played an important role in the country’s economy. Many cities, when faced with a threat of ever-increasing traffic-generated pollution and congestion, tend to adopt policies and strategies that would reduce pollution and congestion.

For the case of the Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Project, complex interactions of local and national actors with international aid agencies offer informative lessons on the pitfalls and opportunities related to the displacement of people caused by transportation infrastructure project construction.

According to Environmental Sourcebook published in 1997 by World Bank, Environmental assessments in the context of urban development have revealed that good practice in environmental assessment has at least three benefits beyond the avoidance or mitigation of adverse environmental impacts (World Bank, 1997):

Early identification of potential conflicts

EA can identify or clarify issues early in the project cycle before they develop into full-fledged problems. For example, EA procedures in the Second Solid Waste Management Project in Mexico helped to identify the role and concerns of scavengers and informal waste collectors. These findings led to a change in project design that addresses both the economic and social needs of this informal sector.

Integration of environmental concerns into the project design

The results of an EA can add to, or even change, the objectives of an urban project. As a result of the findings of an EA for the Second Shanghai Metropolitan Transport Project in China, a program for monitoring pollution levels on the new road and development of a city-wide plan to control vehicular emissions were added to the project’s implementation plans.

Increased institutional capacity for environmental management

In countries that had no specific requirements for environmental assessments at the time of the project’s identification, for instance, Egypt and Sri Lanka, EAs for financed projects helped stimulate environmental measures that would otherwise have been absent.

In countries that have instituted environmental regulations, such as Brazil, China, Indonesia, and Mexico, EAs for urban projects have considerably expanded the scope of national environmental assessment procedures. Many new urban projects include capacity-building components to assist and upgrade local agencies that will implement or monitor environmental management plans.

These agencies may include environmental agencies, departments of public works, sanitation or transportation departments, or water and sewer utilities. Ultimately, these benefits result in better projects with a higher likelihood of successfully achieving their economic, social, and environmental objectives.

Well-designed and implemented resettlement programs can, however, turn involuntary resettlement into opportunities of development such as in the Japanese Ikawa Dam project and the NICs. The challenge is not to treat resettlement as an imposed externality but to see it as an integral component of the development process.

In this regard, it requires the devotion of adequate efforts and resources in the preparation and implementation of the entire resettlement program. Treating displaced peoples as project beneficiaries can transform their lives in many ways that are hard to conceive. This is only possible if the victims are viewed as “project-affected people” who have to be assisted for the project to proceed (Cernea, 2000 9; Budiman, 1989 11).

This paper investigates the impacts of urban transportation development projects on involuntary resettlement. It also endeavors to examine the role of international lending agencies such as the world bank and their best practices in making urban transportation development project socially productive such as it was in the Hong Kong and Singapore experiences where the planning of communities provided decent and affordable housing to resettlers located along the public transportation line.

Background of the project

The environmental impact assessment is an analysis of the negative and positive outcomes that will arise in the environment due to a given project. The assessment takes into account the social, economic impact a project will have on the environment and the possible outcomes.

Once the assessment has been conducted, the stakeholders will make decisions on how the given project will continue and any adjustments to be made to ensure that the project adheres to the recommendation of the Environmental Impact assessment agency.

Environmental impact assessment is clearly defined by the Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Project, Feasibility study on MRT 6 Line. This project will vividly draw valuable lessons on appropriate practices to conserve the environment in urban transportation development projects (Dhaka Transport Coordination Board, 2011 22).

Resettlement of population has been a big issue in both the developing and developed countries due to the issue of involuntary resettlement of the population, though the local population agrees to the benefits arising out of developing infrastructural projects, the displacement of them has always been resented.

“Every year, about 10 million people globally are displaced by dams, highways, ports, urban improvements, mines, pipelines, and petrochemical plants industrial and other such development projects” (Cernea 2000).

Involuntary resettlement of persons usually involves two processes that target the socio-economical lifestyles of the subjects. First, resettlement of persons disrupts the socio-economic structure of a given community as production structures, social lifestyles, and in some cases, income is disrupted temporarily or permanently.

Secondly, resettlement results in disruption of the social framework and formation of new ones, which calls for a thorough assessment of the pros and cons of the project and cautious resettlement and rehabilitation of the process.

The Government of Bangladesh and the World Bank intensively participated in the Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Project in Dhaka city over the last two decades. However, the project which was funded by the World Bank was the one and only such project initiated in the city, and it was finally completed in 2005.

Despite the fact that urban development projects ought to be a process in continuance; the city has not experienced any other transport infrastructure development works.

Therefore, in 2005, a Strategic Transport Plan (STP) was established in Dhaka by the Government of Bangladesh (GOB) in conjunction with the World Bank. The Strategic Transport Plan laid out several key strategic issues inclusive of project implementation, rapid mass transit, as well as an organizational framework.

As of 2008, a preparatory study based on Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Phase1 was conducted in this regard by the Government of Bangladesh, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), as well as other pertinent agencies.

This Phase 1 study was completed in March 2010, and thereafter appropriate proposals were made on short, mid and long-term projects for completion. Urban Transport Network Development Study Phase1focused on MRT Line 1as the initial project and GOB, JICA and other significant agencies began a feasibility study on Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Line 6.

The study included a feasible project plan and a project implementation plan that considered technical, financial, environmental, and social aspects (Cernea, 1997 11). The MRT Line 6 is 20.1km in length, and it includes a total of 16 stations. The line starts from Uttara North, and it passes all the way through Pallabi, Mirpur 10, Begum Rokeya Sharani, Bijoy Sharani, Farm Gate, Sonargaon, TSC, Press Club, Paltan, and it ends at Saidabad.

The study, which is taking place at present, will attend to issues on affected homes, property inclusive of government land, and population right through the entire 20.1km in the projected grand MRT. Eighteen railway stations will need to be constructed, and this will require land acquisition in Uttara, Pollabi, IMT, Mirpur10, Kazipara, Taltala, Agargaon, ChandrimaUddan, Farm Gate, Sonargaon, National Museum, Bangla Academy, National Stadium and Bangladesh Bank. In order to compensate for socio-economic loses, the study will give a proposition providing an ample compensation package in a bid to retain pre-project socio-economic standards for the affected individuals.

Impacts and Risks of Losses Caused by an Infrastructure Development Project

Source: Dhaka Transport Coordination Board (2011)

Therefore, the resettlement issue in Dhaka will also take into account other international Environmental Assessment impact analysis on similar projects and how the governments or authorities. By doing so, they will be taking into account the experiences of other Nations and how they overcame their issues.

From the above facts, there should be a resettlement Action plan in order to minimize the negative effects arising out of resettlement.

Methodology

Proposed Research Approach/Methodology

Qualitative research is a field of inquiry that crosscuts discipline and subject matter. It involves an in-depth understanding of a project and the reasons that govern its approach. Qualitative designs potentially provide a comprehensive understanding of complex social settings and a flexible and interactive process that follows the discovery of unexpected and unforeseen issues.

Qualitative researchers typically rely on four methods for gathering information: Participation in the setting, direct observation, in-depth interviews, and analysis of documents and materials.

The researcher has adopted a qualitative research design because it is concerned with finding out characteristics that describe environmental behavior and factors that affect the performance of a particular sector of the Environmental assessment report. This design makes enough provision for the protection against bias and maximizes reliability. Thus the interviewers will be asked not to express their opinions.

Proposed Design

Data Collection and sources

Study methods will include the use of qualitative and participatory research methodology. Therefore data collection instruments will include structured questionnaires that will be administered.

In-depth interviews will be carried out on community members affected by the Evergreen Rail Line Project, the Ministry of development and Infrastructure and environmental scholars. Secondary data will be used as a source for the literature review, which will include material from articles.

Target Population and sample frame

The researcher will interview the stakeholders in the sector, which include, Scholars of Environmental science, project staff, community Unions, and business unions affected by the project. He will also interview stakeholders from the public to examine the performance of the project board.

Sample

Simple random sampling will also be employed. Random sampling from a finite population gives each possible sample combination an equal probability of being picked up, and each it the entire population to have an equal chance of being in the sample. Random sampling ensures the law of statistical regularity, which states that if on average, the sample chosen is a random one, the sample will have the same composition and the characteristics of the universe.

The Environmental Assessment Certificate offers a framework on how the assessment will be carried out and how the results will be used to determine the projects affected. Under the EAC, both positive and negative effects will be taken into consideration, whereby the assessments will be required to address the following issues:

- The technique used in the depiction of environmental locale and basis for establishing the affected projects

- The underlying principle for choosing the Project-specific, neighboring and national study area limitations, taking into the thought that national study sites may be used as collective effects study areas;

- The level of study applied to each study area, where the local study area will be more intensely studied than the regional study area;

- Any indicators and information basis used to reflect on Project matters

- The environment and degree of impact(s) of whichever relation between the development as well as the baseline situation of the applicable environmental constituent.

- Any intended and existing alleviation measures that are in principle and economically practical for a recognized result

- Every outstanding development effects (i.e., an interaction result that is residual after undertaking planned improvement actions into thought)

Determining whether or not an outstanding development outcome is important by:

- Recounting the precise technique to be used to review the implication of every leftover effect; and

- Taking into consideration the scale, geographic degree, period, reversibility, regularity, the likelihood of the event, and assurance in the evaluation shaping the consequence of leftover effects.

Nevertheless, the methodology adopted will be altered to incorporate the results and recommendations of the Environmental Impact Assessment Committee.

Literature Review

In order to effectively understand involuntary resettlement due to the expansion or construction of new infrastructure, a review will be conducted on other countries that have successfully or unsuccessfully carried out the process.

It will, therefore, incorporate the socio-economic factors of the society in relation to the involuntary resettlement process, which will include the involvement of the community, their desires, consent, their civil rights, and the relocation to new settlements.

In reviewing other involuntary resettlement programs, it would be wise to appreciate that each area/program presents a unique environment, and thus focus should be on areas that share the same urban environment such as Dhaka.

Urban areas face the largest resettlement hurdle due to high population as a result land resource is usually a scarce and expensive recourse. For instance, Doebele 1987 notes, “hillsides and river valleys of every large city in developing nations are crowded with people living in difficult conditions. He goes on to explain the scarcity of land for the urban poor in developing countries was causing trouble in the 1980s and is set to worsen in the future”.

Due to economic development in both developing and developed countries, infrastructure expansion projects are always on the increase, and as a result, involuntary resettlement of the population is always taking place.

Mathur 1995, “it is estimated that every single year, a cohort of at least 10 million people throughout the developing world enter a process of involuntary resettlement. According to him, this is caused by new development projects that are established annually in dam construction, urban, and transport projects.”

In almost all countries, there isn’t precise legislation or laws that govern the resettlement of persons, but what exists are rules governing conveyance of private property. Thus none of the rules take into consideration the involuntary resettlement issue.

For instance, the Indian laws on the land acquisition were enacted in the nineteenth century when the maintenance of law and order, and not development, was the main focus of colonial government administration. “This archaic laws, still operative, are however too weak to meet the problems that people now face due to acquisition of their lands for dams, highways, thermal power stations, mining operations and other similar

Development projects

Most states practice the rule of eminent domain, where the State has the authority/power to repossess any land under its jurisdiction legally. Thus the law operates to the inconvenience of the original landowners, though they are financially compensated for the land, the compensation is never enough as it fails to take into consideration other issues arising out of the involuntary resettlement.

This is due to the fact that the government when awarding the compensation, looks into the market value of the land and not the replacement value of it. As a result of those people who face involuntary resettlement, they rarely re-establish their lies back to the former state there were in before the resettlement.

In Africa, the situation is very much the same. In Africa, Karimi (2005) notes, “when it comes to taking over private land for development projects, the state is under no obligation to demonstrate public purpose. Legal frameworks exist to uphold the interests of the state; not the project affected people.”

Shihata (1991) noted that “in many countries, the national legal framework of resettlement operations is incomplete resettlement legal issues are treated as a subset of property and expropriation law. For various reasons, these national laws do not provide a fully adequate framework for development-oriented resettlement.”

As a result of the lack of a legal framework to address involuntary resettlement issues, the government’s legal system deal with issues arising on ad hoc manner through implementing decisions that are specific to the particular project and thus there isn’t a uniform framework to address the issue, therefore, resulting inadequacies.

Due to this inconstancies and lack of legal frameworks, the World Bank developed a policy to guide the process “The World Bank policy has served as a template for several other policies, such as the policies issued by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and other international development agencies.”

Free Prior Informed Consent

In all resettlement programs, it is vital that all the stakeholders be actively involved in the process whereby their considerations and view on the issue should be factored in. Thus, the concept of Free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) should be factored in the process. This concept calls for a more people-focused resettlement program, as opposed to a project, focused resettlement.

Therefore stakeholders affected by the project are called upon to give their consent on the project and the resettlement program. In doing so, the whole program will be embracing civil and human rights of the community affected, therefore ensuring that the process is free from any encumbrances or legal issues arising during the process. Hill et al. (2010) provide an information guide on how communities can engage project implementers in society.

In addition, they negotiate for shared benefits from such a project and learning more about the same as well as give informed consent. Under this framework, the community is entitled to a proactive role in the project making the project more beneficial to them.

The concept of FPIC has been embraced all over the worlds especially in situations where the projects are more community based or where they intend to benefit the indigenous people where the project is situated.

International Aid Agencies’ Safeguard on Involuntary Resettlement

Hence due to its global applicability, the FPIC concept has been adopted into international law, thereby giving it legal backing.

As a result of the adaptation of the FPIC concept in international law, all major international agencies use the concept in determining the viability of projects and whether the benefits arising will be more beneficial to the local community as opposed to the harm arising out of the involuntary resettlement.

For instance, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) made significant adjustments to its project policies, whereby it focused more on the socio-environmental consciences when funding projects.

Case Study

Evergreen project

This project will conduct an environmental impact assessment on the involuntary resettlement of the population in relation to the construction of the railway line planned for suburban Vancouver.

The construction of the Suburban railway line will present a unique scenario as the construction project is to take place in an urban area that has human settlement and hence involuntary resettlement of the population will have to be done in order to give way to the project.

Under the CEAA, socio-community and socio-economic assessments of the Rail line construction will have to be conducted on the evergreen Line project. The assessment will bring to light the impact the project will have on the socio-economic aspects of the Vancouver environment. Thus assessment will take into account the influence the project will have on the local economy, the residents, its business lifelines, real estate, and the community wellbeing.

Resettlement in Vancouver

It is no doubt that the impending construction of the evergreen railway line will result in involuntary resettlement of the local population to give way to the construction of the rail line as the line is set to bring socio and economic benefits to the Vancouver economy despite this fact, the project must be implemented in a way that the benefits outdo the negative impacts arising.

As the resettlement is involuntary a lot of resistance is bound to arise as the residents will not give their consent in addition, the residents lack alternatives but to agree with the resettlement program Hill et al. (1997 233) notes “infrastructure sustainability is about minimizing impacts and maximizing opportunities across economic, social and environmental dimensions during the delivery of infrastructure.”

Therefore, the resettlement issue in Vancouver will also take into account other international Environmental Assessment impact analysis on similar projects and how the governments or authorities. By doing so, they will be taking into account the experiences of other Nations and how they overcame their issues. From the above facts, there should be a resettlement Action plan in order to minimize the negative effects arising out of resettlement.

Ikawa Dam Construction Project

Ikawa Dam construction project looks into the effects that arise due to involuntary resettlement in Japan. Interviews were carried out on re-settlers of Ikawa Dam, who had earlier on moved and settled into other resettlement quarters. These interviews were undertaken 50 years after their resettlement.

The outcomes of the interviews pinpointed several issues such as, despite the fact that the society was suffering from depopulation and aging, a large number of them were contented with the choices they had made and their livelihood, the re-settlers’ reasons behind their choices were dissimilar, and lastly the chief reason for their contentedness lay in the successful nurturing of their offspring.

It was argued that upcoming resettlement programs would necessitate sufficient attention to re-settlers’ deliberate preferences and also their far-sight in consideration to the next age group.

Construction of dams often results in displacement as well as involuntary resettlement of numerous homes. Particularly in developing countries, the construction of dams has faced disapproval because involuntary resettlement creates the risk of depriving off the resettled people and also adversely impacting the natural environment, although constructing dams is one of the major options for the development and harvesting of water resources.

Japan, as a developed country, has lots of dams that were built in the course of rebuilding and economic progress after World War II. Dam construction has led to the occurrence of numerous cases of involuntary resettlement.

At some point, involuntary resettlement became a main social issue in the country, given that rapid economic growth needed successive dam construction throughout Japan, although the number of affected families was relatively small.

The plight of Japan’s re-settlers had been virtually neglected during the period of the country’s economic development. However, it is not known what happened to the populace resettled in Japan in the long run after the relocation.

In this case study, the experiences and long-term effects of involuntary resettlement in Japan are carefully looked into so as to draw lessons for potential planning and execution of resettlement programs and also for development schemes themselves.

Indeed there are numerous findings from the study of experiences and long-term consequences of involuntary resettlement in Japan and in this case, that of the Ikawa Dam resettlement issue. Firstly it is conclusive that the re-settlers causes that lay behind their decisions with regards to their resettlement were widely different.

Initially, the decisions seemed unanimous among all homes, a factor that the resettlement programs planners had anticipated, but the interview results exposed otherwise (Kusek et al., 2004 156). The outcome showed that the decisions were made by each household separately and independently after putting into consideration their capacity, predilections, and limitations.

The perceptions of both the resettlement program planners and re-settlers were different since the re-settlers did not visualize the program like that that gave emphasis on agricultural growth, including rice farming as a new prospect in the manner in which the planners had planned out. On the other hand, this difference in perception alleviated the possible discontentment of the re-settler due to the blueprint for the new village not being realized.

However, it occurred that in the long run, the re-settlers became satisfied with their living in the resettlement locales, although they did not anticipate much from the resettlement program. Finally, the re-settlers’ satisfaction lay on the successful upbringing of their offspring and, moreover, securing a stable livelihood for the children in the city.

In effect, nearly all the resettlers who had offspring gave a provision of better education to their children up to the point of incurring huge expenses for their children to leave the Ikawa region and remain in the city following the resettlement. It is, therefore, evident that the source for contentment with regards to the resettlers was not suitably planned or integrated into the resettlement program.

Recommendations

One factor that ought to have been considered would have been giving ample attention to resettlers. If the planners give sufficient concentration to resettlers’ prospective preferences and stratagems in complying with the compulsory relocation, they might be capable of developing improved resettlement options.

By so doing, it is vital to note the fact that resettlers and the planners perceive the resettlement options differently. With this in mind, it is, therefore, necessary to incorporate the resettlers in the planning of the resettlement program.

This is a valuable opportunity for the resettle scheme planners to gain knowledge of the resettler’s probable preferences and strategies. Picciotto et al. (2000 79) pinpointed that the realization of income restitution and contentment with resettlement are diverse. The planners should neither treat the resettlers as simple recipients nor victims of resettlement.

For the Ikawa Dam situation, there occurred a number of unforeseen fundamentals that influenced the realization of the new Village Building Scheme on a long term basis. Despite successful child nurturing and the securing of independent livelihoods for the next generation bringing about satisfaction in the resettlement program, it may have been brought about by events outside the control of the resettlement planners (Picciotto, 2001 54)

The second factor to be put into consideration is that of uncertainty in the long run. It is, therefore, vital for the resettlement planners to reflect on unforeseen uncertainty during resettlement planning (Gibson, 2006 279).

This is done so by considering the elements in a bit by bit process, for instance, the planners ought to consider the future of the next generation, the quality of education that will be availed to them, and also the employment opportunities that will be available to them.

The planners ought to look into the kind of life courses that are present in the resettlement area hence employ far-sightedness in the planning of the resettlement project. Although it may not necessarily contain an absolute evaluation of measures against future uncertainty, it greatly assists in giving resettlers responsibility for their livelihoods (Walmsley & Perrett, 1992 123).

China: Guangxi Roads Development

Guangxi Roads Development project was executed in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR) after a loan approval of 150 million dollars. An expressway of 136 km and a highway of 43 km was constructed all the way from Nanning to Youyiguan, which is at the border of Viet Nam across flat and hilly land.

Due to the project, 49 km connector roads to county towns were constructed, the local roads were improved, poor villages were serviced, and there was a provision for both consulting services and training. The project development led to 21 townships, 61 administrative villages as well as 187 village groups in six counties being affected. Guangxi Communication Department (GCD) was the executing agency (EA) for the project.

Resettlement was a key factor that had to be keenly looked into, and Xi’an Highway University was responsible for preparing a resettlement plan in 2000 according to the preliminary technical design and the outcomes of the socio-economic survey and the village survey. County offices that were established were responsible for resettlement consultation, delivery of compensation on time, and also entitlements to affected persons (APs).

Scope of Land Acquisition and Resettlement

The aim of the resettlement process was to attain equality in terms of income so of the resettlers as well as improve the living standards for affected persons in accordance with the People’s Republic of China 1998 Land Law and the Asian Development Bank Involuntary Resettlement Policy.

For cultivating the land, the Land compensation was set at seven times its annual average output value (AOV) while the resettlement subsidy was set at 5-14 times, which varied according to average per capita farmland.

The number of affected homes was approximately 8,671, which was a total of 33,540 people. Due to the increase of land requirement, the capacity of the affected populace rose by 37% from 33,540 people to an estimated number of 46,021 affected persons.

The resettlement operation was carried out on time, and the local authorities permitted the affected persons to choose from a number of resettlement sites that they considered favorable to them. For those farmers that had lost agricultural land, they were awarded the opportunity to choose several apt income replacement options.

As for the resettlement sites, electricity, water, roads, and telephone lines were available. Some affected persons opted to build their houses on land that was contracted, and the resettlement agencies paid compensation for the land (Thukral, 1992 75).

Over 95% of the affected persons lost their land, and many of them were engrossed back into agricultural farming while others were given compensation in the form of cash so that they could indulge in tree planting activities as well as other activities that did not involve farming. The compensation principles were prepared under the Land Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China.

A survey that was conducted by the National Research Center for Resettlement discovered that the resettlers currently possessed more land than before, and this was caused by them farming more dry land that was formerly wasteland. For income and livelihood restoration, the local government provided assistance to the affected persons by:

- Providing job opportunities through hiring them in the construction project,

- Providing vocational training to farmers

- Developing irrigation systems

- Constructing roads

- Reinstating water preservation facilities

- Providing training on enhanced agricultural production

An estimated 82% of respondents who were the affected persons consented that the resettlement operation was successfully carried out, while 79% of them indeed agreed that the affected persons had been consulted accordingly during both planning and during the implementation of the resettlement program.

Tokyo: rail-oriented metropolitan growth

Tokyo metropolitan area has a total of 12 million people, and it generates 17 percent of Japan’s GDP. Greater Tokyo of Tokyo Metropolitan Region (TMR) is within a radius of 50 kilometers, and it has grown to a populace of 32 million people by 1995. The extensive and intensive transport system in Tokyo greatly focuses on rail systems, and it is largely categorized as the most highly developed worldwide.

The rail system takes a total of 43 percent of trips to and fro the 23-ward area, a figure that is quite higher than other modes of transport. Tokyo Metropolitan Region has a 2143 km rail network route, which includes 876 km of East Japan Railway Company (JR East), 996 km of private railways, and 271 km of public subways.

In order to cope with Tokyo’s major traffic constraints, subways have long been perceived as the key mode of public transport apparently which had earlier been buses and taxis. After revisions being made to the initial plan and also emphasis being put on development, the Government then decided to initiate the construction of five lines totaling up to108.6 km in length.

The first development plan of 1958 led to the set up of long-term land-use policies; hence, it initiated the controlling of the concentration that quickly took place in central Tokyo. It also promoted the dispersal of the populace as well as jobs towards external areas. In the event, various land-use policies were embarked upon so as to accomplish these objectives.

The land-use policies actively took part in the growth and expansion of the metropolitan area. A broad development plan for the Tokyo Metropolitan Region was profoundly undertaken by the National Government, which depended on the long-term land-use policies. Due to the initial development plan that dwelled on the control of population and employment concentration in central Tokyo, a couple of measures were embarked upon. These measures were:

- The advancement of allotment facilities in outer areas

- Management of construction of factories and social amenities

- The building of protectorate towns

- Development of municipal houses in uptown locales

One of the planning strategies that the Tokyo Government employed was that of land readjustment system that aided in the effective acquisition of rail rights-of-way. Since involuntary resettlement is caused by transport projects, it is, therefore, vital to minimize resettlement caused by displacement by transport projects.

A good manner in which resettlement can be greatly reduced has been addressed so as to ascertain that proper treatment and compensation is given to the victims of involuntary resettlement. A way of minimizing the probable disruption to residential neighborhoods by urban rail projects is by making use of already existing rights of way.

Involuntary Resettlement: The Large Dam Experience

The World Bank undertook a study of involuntary resettlement by countries caused by potential dam construction. The study shows that those member countries that lack the capability and dedication to tackle involuntary resettlement properly ought to abandon the idea of embarking on the construction of a dam.

This study covers a total of six countries, namely: China, India, Thailand, Brazil, Indonesia, and Togo. The dams were constructed in densely populated regions hence resulted in high numbers of resettlers.

In Karnataka, India, two dam projects would relocate a total of 40000 homes, and this was the largest resettlement operation in the country’s history. Furthermore, a total of 150000 people would have to be resettled once the ultimate height of the dam is elevated.

Due to limitations brought about during the implementation process, the Bank was forced to suspend the construction project twice. In the area, the resettlement conditions gradually improved, and the compensation rates reach the market levels. Resettler incomes increased gradually.

While in Maharashtra, construction of twin smaller dams led to the resettlement of approximately 40,000 people, and the resettlers were relocated to a downstream region, which is usually irrigated by the reservoirs. While some resettlers adapted well to the resettlement plan, many of them endured a difficult time since they did not receive the irrigation and the few that did only received inadequate quantities of the water.

In china at Shuikou, a total of 67,000 people were resettled from the Valley floor, and 17000 people were resettled from the city of Nanping, which is located at the upstream end of the dam, this move avoided the resettlement of nearly 200,000 residents of Nanping.

The resettlement activity in the area was completed in 1992. The original resettlement plan planned for 74 percent of the resettlers to be rehabilitated using traditional agricultural methods, but eventually, 75 percent ended up being rehabilitated through other different methods.

The local government actively participated in creating employment for the resettlers since it established fishery reservoirs, fruit and timber trees, and township enterprises and even went ahead to enlist foreign investors so as to institute industries in order to create job opportunities.

In the event, the earning of the resettlers improved to 44 percent by 1996. Thus it is evident that handling resettlement as a development prospect results in flourishing resettlement results.

In Yatan, 43,000 residents were resettled while the incomes of another 19,000 people were adversely affected. The town was not a beneficiary of the booming coastal economy, but despite that fact, the resettler revenues increased, and they were complemented by a grain ration up to the point when the target level was attained.

The local government made arrangements for the relocation of several thousand homes to other regions of the province, particularly to two sugar farms and a state farm.

China handled the resettlement issue more as a development opportunity than as a problem. The two projects at Shuikou and Yantan proved how well proper resettlement practices could result in successful and speedy revenue restoration to the affected homes, despite the fact that huge capacities of people were forced to move to farms that were less productive for farming.

Both projects resulted in the river valleys being filled, and they were bordered by steep hills. This forced the resettlers to abandon the traditional paddy farming so as to indulge in intense farming in crops, tree crops and also to get non-farm employment.

In some instances, particularly in Yantian, households were forced to move to other regions in order to get employment. For most households, their incomes increased significantly in spite of the change in their lifestyles. For resettlers in Shuikou, their housing resettlements have improved as well as services offered to them, and the resettlers themselves are contented with that factor.

A robust regional growth led to the fiscal upgrade of households from Shuikou, while the Yantan families did not experience this economic improvement. Many of the resettled homes reinstated and increased their earnings rather rapidly in both Shuikou and Yantian.

China, as a country, showed great diligence in carrying out the two projects. When a shortage of resources occurred, the resettlement agencies had the determination to keep up with the schedule, and they eventually succeeded.

The involuntary resettlement process in the country was handled rather marvelously since the resettlement agencies emphasized employment and incomes for the resettlers and even incorporated the potential resettlers and the local authorities in the planning and implementation process of the resettlement plan.

This shows that China views income restitution and progress as an important aspect as it views the physical relocation of people. Resettlement, according to the country, is an opportune event for regional growth.

The income policy at Shuikou was passed along warmly due to the quick industrialization that occurred in the southeastern coast of China. As for Yantian, their employment creation process and revenue restoration process has been rather dawdling (Phelps & Mohan, 2010 63).

In Pak Mun, Thailand, the power company that constructed the dam altered the initial blueprint by reducing the height of the reservoir by five meters and shifted it upstream by 1.5 kilometers. This course of action decreased their power remuneration by a third and decreased the dam size by slightly more than a half. The households that were close by the dam were resettled.

Moreover, the compensation charges were approximately 8,750 dollars per hectare, and this munificent offer allowed resettlers to change their livelihoods and thus obtain possessions. Six percent of the earnings were spent on the purchase of land since farming activities brought about diminishing returns.

In Indonesia at Kedung Ombo, it was originally planned that 21,600 people that were to be relocated were to enlist in the transmigration program and hence set off Java to the external islands. Out of the 90 percent planned for, only 25 percent made it to the outer islands due to major delays in the development of the transmigration sites.

Approximately 60 percent of the residents ended up resettling in the dam area, and many of them took up employment in close by municipalities. The incomes of the resettlers increased tremendously due to the rapid growth in the central Java economy.

The transmigrants had varying outcomes where some received fertile land while their neighbors received land that was poor for agricultural activities. While some of the resettlers made good earnings out of the oil palm plantings they had received, others still waited up to 12 years on. A poor follow up in examining whether the resettlement plans were in order was made; hence, the resettlers’ conditions were not monitored effectively.

In Itaparica, Brazil, the reservoir that was constructed was done so without financial backing from the bank, but eventually, the bank agreed to it that it would provide finances to the resettlement scheme as a component of a power sector loan.

The resettlers who totaled a figure of 49,500 formed a syndicate and claimed for irrigation plots that were close by the dam. The resettlement costs for the resident became quite costly, and they rose past 1 billion dollars, and before the resettlement completed, they have reached 1.5 billion dollars or about 200,000 dollars per home.

On the other hand, for the homes that accepted the compensation option, they were given about 5,000 dollars with which they were to resettle themselves. For those resettlers that received irrigated plots of land, they had to depend on free irrigation water as well as revenue maintenance expenses. For the resettlement planners in this scenario, resettlement proved to be a very costly affair.

Lastly, in Nangbeto, Togo, the constructed dam displaced a total of 10,600 residents of whom 3,000 people lost their homes while the other 7,600 were resettled about 30-55 kilometers away from their original homes. The resettlement areas in Nangbeto were initially sparsely populated, but after 1987, this change to over-population due to the factors of in-migration as well as natural growth.

A decline in farm produce and proceeds was caused by the lack of adequate incomes to purchase farm inputs, fertilizers as well as approved quality seeds. This shows that monitoring and follows up are vital for successful resettlement to be achieved.

Good response by numerous governments would be handling resettlement more as an opportunity than as a setback. In order to do so, the governments ought to use mix land-based and also diversified strategies in that they would reinstate not only the resettlers’ revenues but also improve their livelihoods.

Resettlement planners should plan for revenue-generating opportunities prior to the resettlement, and they should progress in evaluating how the resettlers are coping up long after their resettlement. Lastly, the resettlement planners should incorporate the private sector, non-governmental organizations, and also the government bureaus so as to ensure the plan becomes successful.

The resettlement preparations in Brazil, Togo, India, and Indonesia were delayed due to the mere fact that the resources relocated to the projects were scarce. In Thailand, on the other hand, sufficient resources were allocated to the project, and the resettlement planners attained satisfactory results. A deteriorating aspect of resettlement planning is the resettlers’ economic rehabilitation.

This is vividly evident, as in the case of Togo, where the resettlement planners did not consider the economic rehabilitation of the resettlers. This led to the depleting of the livelihoods and incomes of the resettlers over a long period of time without the realization of resettlement planners.

As for Kedung Ombo, Itaparica, and Karnataka, the strategies that were enacted to look over the transmigration process were not viable for a large capacity of the resettlers. This is heavily criticized for the resettlement planners’ failure to deal with the operating restraints as required. As a result, the planners were obligated to result in second-best strategies.

These case studies prove that despite the fact that intelligent planning is vital, over-reliance on these plans may be hazardous to the resettlement process. As in the case of Indonesia, the plans indicated that many residents in the potential reservoir area were willing to be resettled elsewhere, but when the resettlement process began, the number declined rapidly since many people had changed their perceptions towards the transmigration program.

As for China, the established plans gave an assessment that a larger capacity of residents had the opportunity to get employment in the farms, but in the end, this proved not to be the case. Alterations, therefore, had to be made in the resettlement plans. Good planning, which leads to good implementation, does not necessarily apply in involuntary resettlement.

In all the projects of the six respective countries, the implementation process of the resettlement plans did not follow the resettlement plans. This was caused by the failure of the implementation process to follow the timetable keenly.

China is one of the countries that carefully monitored the outcome of the resettlement program, and due to the flexibility it had, the country changed its resettlement plans when it deemed right. China changed its land-based income restitution strategy after farm employment did not attain the intended levels; this is an exemplary example.

Framework

Framework on Resettlement

Present land uses include municipal properties for transportation, public facilities, parks and recreation, trade, and commercial/industrial (light and heavy) property. The Dhaka project Line is expected to be situated mainly on privately held property and public streets and parcels.

In certain areas, this may require the widening of some roads. An initial examination shows that the property needed for the project will be made up primarily of public streets, and residential, commercial, industrial parcels, and rail rights-of-way. Property acquisition consisted of part and entire parcels as well as right-of-way and also land for Vehicle Storage Facility and probably for building staging and laydown areas.

In the scenario where a minority group is implicated, the project design tends to shun involuntary resettlement. For preparation purposes, consultations between ethnic and religious leaders ought to be made as well as the inclusion of social scientists in resettlement planning.

A supporter should also involve the PAPs to be directly engaged in the resettlement process. Also, there is a need to resettle those affected in lands productively equal, preferably within fields of conventional occupancy (Bartone et al., 1994 236).

It is expected that the Project will have to acquire land and some properties along the route to construct infrastructure and other supporting facilities. This can only be implemented if people along the project route are resettled. Thus it will cause involuntary settlement.

Involuntary resettlement is an intricate issue since people losing incomes and livelihoods from being it farmlands, forest, commercial premises, and other production resources, must be compensated, or alternatively productively equal assets provided, if Project Affected Persons (PAPs) are to regain and improve their lives and economic output (World Bank, 2004 67).

In Dhaka, there is an overarching planning framework for urban investments that puts environmental and social constraints into consideration so as to considerably reduce the incidence of environmental and social impacts as cities develop.

Involuntary resettlement causes both social as well as economic disruptions, apparently which are prevented by the project policy. In cases where compulsory resettlement is unavoidable and fully justified, the project has formulated a resettlement plan to make sure that individuals displaced are provided development opportunities to improve and regain their way of life they had before the project.

The project intends to collaborate with the affected property owners or their designated agent through a property acquisition process, which will discuss the amount of property needed and to negotiate a purchase price based on market value, as stipulated by the independent assessment.

The intention of the project is to come to a consensual agreement with property owners that will be reached through a negotiation process (Dubernet, 2001 101).

In the case the project managers and the property owner are not able to reach a consensus with an owner, the Government has the power to obtain land by expropriation, though this is the option of last resort. In such a case, provincial legislation sets up a way for independent ascertainment of compensation (Besden, 2009 268; Appa & Girish, 1996 148)

The types of losses due to the undertaking of the Project include:

- Loss of land (homestead, commercial, agricultural and pond);

- Residential/ commercial/ community facilities;

- Loss of trees and crops;

- Loss of workdays/incomes due to dislocation and relocation of households and businesses;

- Loss of rental premises; and

- Loss of access to land and residences and trading places.

The following categories of Project Affected Persons (PAPs) are expected to be affected at the time of implementation of the project:

- Project Affected Persons whose land is impacted: PAPs who have land that is being used for agricultural, residential or business courses and are impacted either partly or totally and the effects are either short or long-term;

- PAPs whose structures are affected: PAPs who have infrastructures (including auxiliary and secondary infrastructures) are being used for residential, or worship use that is affected partly or totally and the impacts are either in the short or long-term;

- PAPs with other assets affected: PAPs whose assets, such as crops or trees, are being affected either in short or long term;

- PAPs losing access to vested and nonresident property: PAPs who are enjoying access to the vested and nonresident property, both owned and purchased, will be losing their right to cultivate and use those lands when acquired;

- PAPs losing revenue or livelihood: PAPs who have their businesses, sources of revenue or livelihood (that includes employees of affected businesses) being affected partly or totally, and impacted either in the short or long term;

The Resettlement Action Plan has the following precise principles based on the government provisions policies:

- The land acquisition and resettlement effects on individuals impacted affected by the sub-projects would be avoided or reduced considerably through alternate design alternatives;

- Where the negative consequences cannot be avoided, the PAPs and vulnerable groups will be identified and helped in advancing or recollecting their way of life;

- Information pertaining the drafting and carrying out the resettlement plan will be revealed to all stakeholders and individuals participation will be ensured in drafting and implementation;

- The affected persons who are neither land nor property owners, but have economic interests or will be losing their incomes or livelihood will be helped as per the broad principles described by the Resettlement Action Plan;

- Before acquiring the required lands and properties, compensation and Resettlement and Rehabilitation (R&R) help will be paid according to the guidelines given by the Resettlement Action Plan;

- A compensation matrix for various categories of individuals impacted by the project was formulated. Individuals resettling in the project area after the cutoff date will not be entitled to any help;

- Proper complaint redress channel will be set up to make sure disputes are resolved fast and effectively;

- Talks with the people affected by the project will continue at the time resettlement, and rehabilitation operations are implemented;

According to the resettlement policies provided for the Project, all PAPs will be entitled to a total of compensation packages and resettlement help according on the nature of tenure rights on lost possessions, extent of the impacts as well as social and economic liabilities of the affected persons and measures to maintain livelihood reinstallation if livelihood impacts are predicted (Asian Development Bank, 1998 18). The PAPs were entitled to:

- Damages for land, properties or assets lost at their replacement value;

- Damages for properties and other resolute possessions at their replacement value;

- Help for business/salary revenues lost;

- Help for moving; and

- Reconstructing and or restitution of community resources/amenities and services.

These provisions are to make sure that individuals affected by land acquisition, whether titled or non-titled, will be entitled to adequate compensation/resettlement benefits. Individuals with no legal entitlement but use the land under acquisition if resettled for the Sub-project use would be awarded compensation and resettlement benefits for properties and moving or reconstruction allowances (Vanegas, 2003 5369).

People with customary entitlements to land and physical properties like the proprietors and tenants of vested and commercial properties, tenants of homesteads, business, and agricultural land, and tenants of land and structures, among others, are also addressed in the RAP.

The Resettlement Action Plan also creates opportunities for work-related skills development training for revenue-generating activities for the affected persons, particularly for the vulnerable individuals (Shen et al., 2007 281).

The individuals forcibly resettled by the project are entitled to priority access to these revenue restitution plans. The resettlement plans of the Project are to be implemented in consultations with the affected persons, and all measures put in place to reduce disruptions as the project is implemented. The affected persons’ choices will be put into consideration in selecting the option relocation sites (Zhang & Mikah, 2001, 355).

Environmental Impact Assessment of Resettlement

The Dhaka Project was subjected to Environmental Assessment (EA) appraisal under the Environmental Assessment Act, which includes a full review of potential project-associated consequences and proposed mitigation measures.

The environmental assessment purpose was to identify the prevailing conditions for fisheries, vegetations and wildlife, water quality, air quality, polluted sites, archaeological sites, noise, and social and community characteristics (Partridge, 1989 381). This process will give a basic input for impact assessments that includes potential environmental and social and community impacts together with planned mitigation mechanisms.

The Senegal Government obtained an Environmental Assessment Certificate at the time of commencement of the project construction. The Environmental Assessment Certificate describes the Ministry of Transportation’s move towards environmental administration, supervision, and scrutiny at the time the project is implemented.

The Environmental Management Program consists of a Construction Environmental Management Plan and an Operation and Maintenance Environmental Management Plan, with sub-components plan to handle matters, like residue and erosion control, and reconstruction of disturbed regions (Mirza, 2006 645).

In addition, the Certificate outlines the Ministry’s plan for identifying the precision of the project’s EA (compliance monitoring) and for determining the efficiency of mitigation actions applied to mitigate or reduce negative impacts at the time of constructing and operating (response monitoring).

When the construction began, a comprehensive Environmental Management Plan was designed by the Ministry of Transportation and submitted to the Senegal Environmental Assessment Office and other related regulatory bodies for assessment and recommendation prior to service commencement.

In cases where involuntary resettlement cannot be avoided and fairly reasonable, usually, the Ministry’s regulation policy requires that a resettlement plan be devised and established to make sure that those displaced are provided development opportunities to improve or reconstruct their lives (Scanlon & Simon, 2010 49).

The first goal of an Environment Assessment on a resettlement project should be to ascertain the ability of the receiving area to maintain the added population under the situation created by the resettlement operation (Biswas et al., 1992 24).

The second goal of the Environmental Assessment is that it ought to identify environmental perils the plan possesses.

Thirdly, an Environmental Management Plan, should be prepared that looks at these hazards to ease impacts on and look after the natural, human-made, and social settings (World Commission on Dams, 2000 17).

Societal facets of Relocation

There are a couple of vital yet circumlocutory public effects of secondary development that are overlooked in both project design and monitoring. Some of these impacts can be foreseen, rather reliably, based on past experience, while others are unanticipated and can only be seen and handled if an ample system of impact monitoring is implemented at the time of project implementation (Leitmann, 1994 56).

Involuntary resettlement is one of the problematic facets of development projects. The main cause has been a failure to come up with a universal resettlement plan in the area that often leads to under-planned and under-financed resettlement components that turn into relief instead of development operations (Guggenheim, 1994 14; Ding, 2005 11). Both poverty and environmental decay are the most considered environmental effects of bad resettlement procedures.

The peril of poverty in involuntary resettlement operations is significant due to the loss of a source of income or livelihood. Thus, the resettled community must maintain the able-bodied and also the less productive individuals, like the aged, the handicapped, and the unskillful. In addition, the well-off and better-exposed families are likely to divide, taking with them the essential factors of production and capital resources, which create opportunities for the locals, leaving the desperate locals to be resettled (Bose et al., 2001 177).

Existing Environment of the Project Area

The comprehensive Socio-Community review is presented in Section 9 of the EAC Application, and the comprehensive Socio-Economic Assessment is documented in Section 10 of the Application, with key findings summarized in Section 23: “Summary of Project Impacts, Mitigation Measures and Potential Residual Effects.”

The Environmental Assessment (EA) process contains a detailed assessment of potential Project-related impacts. The Ministry has engaged environmental experts to perform several comprehensive surveys. The aim of these surveys is to make sure that the Ministry has adequate information to develop and implement suitable actions to prevent or reduce impacts (OED, 1996 36).

Mitigation Measures

Mitigation of loss of land and properties and livelihoods is the main purpose of the resettlement plan. Further mitigation measures are to be taken to offer adequate assistance to the income generation restoration facets of project-affected households (Scudder & Colson, 1982 277).

Briefly, mitigation of losses and restitution of the socio-economic position of the affected persons are the main goals of the resettlement plan (Davison, 1993 15; Takahashi, 2004 39). The main aspect of the resettlement plan is to offer institutional and financial help to PAPs to restore their lost assets and sources of income. For this reason, the project formulated a policy to compensate individuals who were impacted by the implementation of the project.

A review of the social impacts on the environment will cover a broad demographic examination of the people living along the project route and also look at the local resources and seasonal resource management programs (Goldar & Banerjee, 2004 121).

The purpose of the environmental assessment will be looking at the extent of the anticipated impacts of sporadic development, so that mitigation measures are planned adequately. The nature of the local and regional institutions that are responsible for planning and managerial decisions will be adequately analyzed (Caspary, 2009 22; Weaver et al., 2008 96).

Monitoring

The EMP includes particulars for any monitoring programs that may be needed by provincial or federal institutions involved in the Project assessment or specific permitting or approval to make sure that supporter commitments are met at the time of construction and operational stage of the Project (OED, 1998 23; Listorti, 1990 47).

The monitoring system will evaluate from time to time the impacts of development intervention or induced development that are not predictable or expected at the beginning (Caspary, 2007 75).

These impacts could include the rise of unanticipated diseases or the informal establishment of environmentally unsafe or population attracting businesses or entrepreneurs due to the general economic growth in the area, for instance, people living adjacent to big construction sites which develop skills at the time of construction may later establish informal enterprises that call upon their acquired skills.

In the case where many such people establish new businesses, this leads to an unanticipated creation of new businesses, with potential noise, air, or water pollution or insufficient waste disposal (Eriksen, 1999 45; Dwivedi, 2002 724).

Environmental Management Plan (EMP)

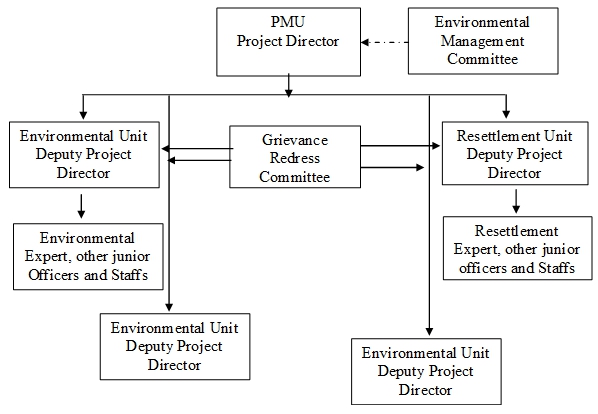

Project Level Institutional Framework

An Environmental Unit would be created for the Evergreen Line Project at the time of detail design and construction stage. A provisional organ gram of the Unit as follows:

Environmental Management Plan

Environmental management is important to make sure that the impacts identified are avoided and mitigated by the Environmental Management Plan (EMP). The EMP is formulated in the general framework of the BC MoT’s environmental policies and standards, and also includes significant design information available from both the Canada Line and Millennium Line projects ( Charmaz, 2006 69).

The Environmental Management Plan details actions to address the potential impacts listed above, which will be carried out at the time of the construction stage of the project, including:

- The framework for construction organization and supervision.

- Necessities for the workforce.

- An explanation of activities to be carried out during the construction stage.

- Procedure for workers’ health and safety, fire protection, and prevention.

- Environmental management necessities for this stage included in specific section plans.

The EMP was prepared at a conceptual level and finalized before the construction work began. The execution of the EMP shall be monitored to make sure overall potential environmental and safety impacts can be avoided urgently and can be simply mitigated by taking the best engineering practices.

Environmental monitoring and management have been incorporated into the project management and reporting system (Asian Development Bank, 2008 63; Uslan et al., 1990 41).

The Ministry and other relevant authorities will be engaged in auditing the project ongoing and will take delivery of copies of monitoring reports. These bodies or institutions may also request an increase in the frequency of monitoring and that suitable measures are taken for environmental mitigation as they consider essential (Scudder, 1997 55).

Reporting

Generally, all types of social Environmental impact assessment are found under the Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) framework. Hence all reports and recommendations will be based on the social impact of the project. Therefore as the Dhaka project is implemented, there will be a continuous assessment on the project on the Environmental Impact Assessment, where there will be reports made at even intervals throughout the project.

The report will be forwarded to the directors and the Ministry of transportation (Marsden, 1998 24). The reports will be crucial to the whole project and resettlement program as they will act as watchdogs on the success of the rehabilitation, and any constraints arising will be quickly addressed. In addition, there will be board meetings for all stakeholders, including the public, at regular intervals in order to address any issues arising (Davidson 1993).

As a result, the Government opened a project office that is opened to the public. The Purpose of the project office was to press forward the project through planning and design by giving the local community a chance to be involved in the process.

During these meetings, the project staffs are able to get the first-hand report from the public give feedback to them in a timely manner as the project continues (Jing, 1999 88; Pope et al., 2005 295; Nakayama, 2004 950).

Discussion

As the global economy improves and the population increases, Governments around the world have appreciated the fact that more infrastructure projects are needed to support the socio-economical growth. The need of new transport infrastructure is to cater for the increase in traffic congestion, pollution from numerous small scale transport system and thus the need for large scale transport system that reduce environmental pollution (Gill, 2006 99).

Thus transportation infrastructure has played a pivotal role in support of the agenda. Transport is a crucial pillar of economic growth. Thus there are numerous transportation projects being undertaken all over the world. Transportation projects require large tracks of land to support the infrastructure.

Nevertheless, due to the large population in the cities, there is insufficient land for new projects, which calls for involuntary resettlement for local communities affected by the project. As a result, there have been conflicts and destruction of the local community as the national economic needs conflict with the local interests.

Due to this, the Government has to conduct an environmental impact assessment on the local area affected by the Evergreen railway line project. By conducting the EA, the stakeholders will be able to inter-relate the desires of the national government and the local communities affected (Basu, 2006 87)

“According to Environmental Sourcebook published in 1997 by World Bank, Environmental assessments in the context of urban development have revealed that good practice in environmental assessment has at least three benefits beyond the avoidance or mitigation of adverse environmental impacts” (World Bank, 1997):

- Early identification of potential conflicts- by undertaking an Environmental assessment evaluation, it can quickly bring to major light issues that are bound to arise in the course of the project. Thus they assist the project co-coordinators in forecasting future problems and averting them before they run the project into a stall.

- Integration of environmental concerns into project design- Findings from EA can be incorporated into the project in order to ensure the project is community-oriented and not project-oriented.

- Increased institutional capacity for environmental management- The ministry of development and infrastructure has to conduct EAs for any project they intend to undertake. As a result, it has increased the awareness and importance of the EA. It has thus expanded the scope of Canada’s Environmental Impact Assessment with the establishment of CEAA.

The Government has established environmental agencies that monitor the environment and any changes that are bound to occur due to human interference. Due to these agencies, the monitoring of projects and their impact on the environment has resulted in better projects and less harm to the environment (Gutman, 1995, 19).

It’s also widely acknowledged that infrastructural developments require land, but due to the high population of human settlements along transport corridors, resettlement of the local communities has been an issue to deal with.

References

Appa Gautam and Girish Patel. “Unrecognised, Unnecessary and Unjust Displacement: Case Studies from Gujarat, India”, in Christopher McDoweIl (ed). Understanding Impoverishment: The Consequences of Development-Induced Displacement. Providence/Oxford: Berghahn Books, (1996): 139-150.

Asian Development Bank. Asian Development Bank’s Involuntary Resettlement Safeguards: Project case studies in India. Manila: Asian Development Bank. 2008.

Asian Development Bank. Handbook on Resettlement – A Guide to Good Practice. New York, NY: John Wiley. 1998.

Bartone Carl, Bernstein Johnson, Leitmann Hill and Jill Eigen. Towards Environmental Strategies for Cities: Policy Considerations for Urban Environmental Management in Less-developed countries. The World Bank. Washington, D.C. 1994.

Basu, Malika. “Gender Focus in Resettlement Planning”, in Hari Mohan Mathur (ed). Managing Resettlement in India: Approaches, Issues, Experiences. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 2006.

Besden Carl. “Design of a map and bus guide to teach transferable public transit skills”. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, Vol 103, (2009): 267–270.

Biswas Hunter, Asit Kante and Sintax Agarwal. Environmental Impact Assessment for Developing Countries. Oxford/Boston: Pollution Control Research Institute, Butterworth–Heinemann. 1992.

Bose Pitok , Pattnaik Boris, and Mittal Mikush. “Development of socio-economic impact assessment methodology applicable to large water resource projects in India”. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, Vol 8 No 2, (2001): 167-180.

Budiman Arief. Involuntary Resettlement: Lessons from Kedung Ombo. Jakarata, CA: Sage Publications. 1989.

Caspary Georg. “Assessing, mitigating and monitoring environmental risks of large infrastructure projects in foreign financing decisions: the case of OECD-country public financing for large dams in developing countries,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, Vol 27, No 1(2009): 19-32

Caspary Georg. “Mitigating and monitoring the human impacts of development-induced displacement: the case of OECD-country financing for large infrastructure projects”. Human Security Journal, Vol 2, no 1, (2007a): 63-79.

Cernea Michael. “Involuntary Resettlement: Some Thoughts on Research Priorities”, The Eastern Anthropologist, Vol 53, No 1-2, (2000): 3-12.

Cernea Michael. “Risks, Safeguards, and Reconstruction; A Model for Population Displacement and Resettlement”. In Michael M Cernea and Christopher McDowell. (eds) Risks and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees. Washington DC: The World Bank. 2000

Cernea Michael. Risks and Reconstruction Model for Resettling Displaced Populations. The World Bank Environment Department. 1997.

Charmaz Kane. Constructing Grounded Theory — A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 2006.

Davidson Fuller. Relocation and Resettlement Manual: A Guide to Managing and Planning Relocation. Rotterdam: IHUD. 1993

Dhaka Transport Coordination Board. “Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Project.” Environmental Impact Assessment Study, 2011.

Ding Geoffrey. “Developing a multi-criteria approach for the measurement of sustainable performance”. Building Research and Information, Vol 33, no 1, (2005): 3–16.

Doebele William. “The Evolution of Concepts of Urban Land Tenure in Developing Countries”. Habitat International. Vol 11. No. I. (1987): 7-22.

Dubernet Carlton. The International Containment of Displaced Persons: Humanitarian Spaces Without Exit. Ashgate, Aldershot. 2001.

Dwivedi Riva. “Models and methods in development-induced displacement”. Development and Change, Vol 33, (2002): 709–732.

Eriksen Jackson. “Comparing the economic planning for voluntary and involuntary resettlement”, in M. Cernea (Ed.), The Economies of Involuntary Resettlement: Questions and Challenges, World Bank, Washington, DC. 1999.

Gibson Randy. “Beyond the pillars: sustainability assessment as a framework for effective integration of social, economic and ecological considerations in significant decision-making”. Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, Vol 8, no 3, (2006): 259–280.

Gill Maninder. “Large Dam Resettlement: Planning and Implementation Issues”, in Hari Mohan Mathur (ed). Managing Resettlement in India Approaches, Issues, Experiences. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 2006.

Goldar Barney and Banerjee Nikal. “Impact of informal regulation of pollution on water quality in rivers in India”. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol 73, no 2, (2004): 117-130.

Guggenheim Scheimer. Involuntary resettlement: an annotated reference bibliography for development research. The World Bank, Washington, DC. 1994.

Gutman Pablo. Urban Issues in Environmental Assessment: A Review of Five Recent Bank Projects. Washington, D.C. 1995.

Hill Carey and Peter Bowen. “Sustainable construction: principles and a framework for attainment”. Construction Management and Economics, Vol 15, no 3, (1997): 223–239.

Hill Christina, Lillywhite Serena, and Simon Michael. Guide to Free Prior and Informed Consent. Australia: Oxfam, 2010.

Jing Jyong. “Displacement, Resettlement, Rehabilitation, Reparation and Development” The China Report. Vol 2, no. 1, (1999): 45-89.

Karimi, Singh, Nakayama Malia, Fujikura Randal, Katsurai Iwata, Mori Tiksen & Mizutani Kintal. “Post-project review on a resettlement programme of the Kotapanjang Dam project in Indonesia”. International Journal of Water Resources Development, Vol 21, (2005): 371–384.

Kusek lilac, Jody Zall and Ray Rist. Ten Steps to a Results based Monitoring and Evaluation System. Washington, USA: The World Bank. 2004.

Leitmann Josef. Rapid Urban Environmental Assessment: Lessons from Cities in the Developing World. The World Bank. Washington, D.C. 1994.

Listorti Josef. Environmental Health Components for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Urban Projects. Washington, D.C. 1990.

Marsden David. “Resettlement and Rehabilitation in India: Some Lessons from Recent Experience”, in Hari Mohan Mathur and David Marsden (eds). Development Projects and Impoverishment Risks: Resettling Project- Affected People in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press (1998): 22-41.

Mathur Hari Mohan. Struggling to Regain Lost Livelihoods: The Case of people displaced by Pong Dam in India. Oxford. 1995.

Mirza Silk. “Durability and sustainability of infrastructure — a state-of-the-art report”. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, Vol 33, no 6, (2006): 639–649.

Nakayama, Mintra. “Japanese experiences in resettlement for dam construction”: Proceedings of the 2nd Asia Pacific Association of Hydrology and Water Resources Conference, Vol. 2, (2004): 948–953.

OED. Recent Experiences with Involuntary Resettlement-India-Upper Krishna Project. Washington DC: The World Bank. 1998.

OED. The World Bank’s Experience with Large Dams: A Preliminary Review of Impacts. Washington DC: The World Bank. 1996.

Partridge Backer. “Involuntary resettlement in development projects”, Journal of Refugee Studies, Vol 2, no 3, (1989): 373-384.

Phelps Allen and Mohan Horman. “Ethnographic theory-building research in construction”. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol 136, no 1, (2010): 58–65.

Picciotto Rilley, eds. Involuntary Resettlement: Comparative Perspectives. Transaction Publishers. New Jersey. 2001.

Picciotto, Robert, Edward Rice and Warren Van Wicklin, eds. Involuntary Resettlement: Comparative Perspectives. New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): Transaction Publishers for the World Bank. 2000.

Pope Johnstone, Allan Morrison-Saunders and Dianah Annandale. “ Applying sustainability assessment models”. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, Vol 23, no 4, (2005): 293–302.

Scanlon Janice and Simon Hodgson. “Delivering urban rail sustainably. In Special Edition Issue 2 Rail Express”, Critical Issues for Rail’s Key Areas, (2010): 48–50. Australia: Informa

Scudder Thayer. “Resettlement”, in Asit K Biswas ed. Water Resources: Environmental Planning, Management and Development. New York: McGraw Hill. 1997.