Introduction

The problem addresses issues related to gender and incarceration in the United States. Every person in state custody needs to be treated with decency and respect, and people should never forget that female convicts have historically been disproportionately susceptible to abuse (Tully). Acceptance of sexual abuse and violence of inmates have endured for many years and continues to this day (Tully). Additionally, discriminatory criminal justice policies and practices have unjustifiably harmed Black people at all levels of the justice process, including disparities in the implementation of supposedly race-neutral legislation (“Incarceration Trends in Indiana”). Long-term incarceration typically has long-term consequences for women, ranging from financial difficulties to strained connections with their children (Levin). The proposed policy’s first and most significant objective is to enable the highest level of security for imprisoned women and their children regardless of their race or sexual orientation.

Scope of Problem

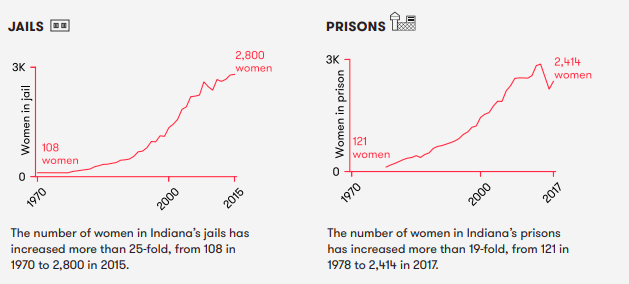

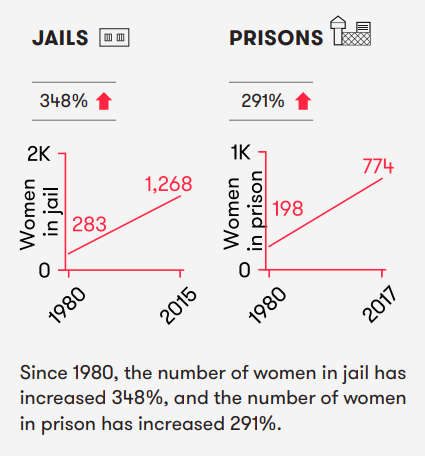

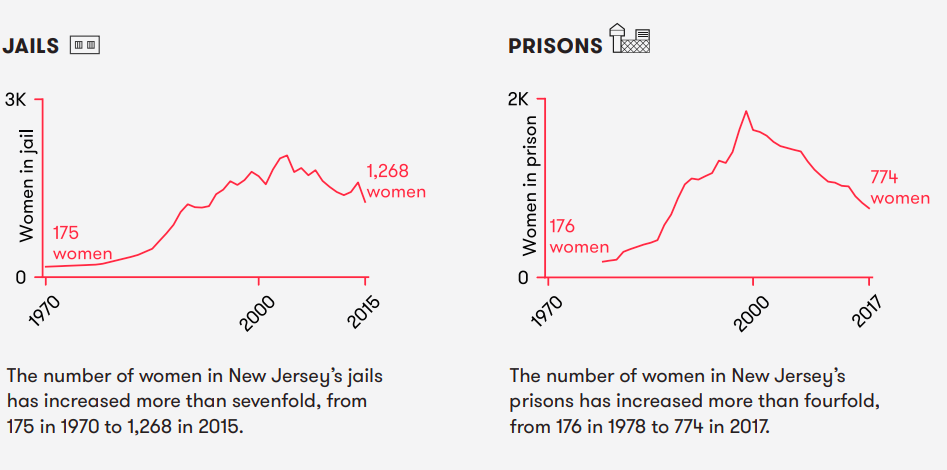

The problem considers the vulnerability of female inmates and the well-being of their children. Levin states that at least five million children have an incarcerated parent; the cost is high, ranging from precarious accommodation to long-term consequences on their health. Since 1980, the proportion of jailed women in the United States has increased by more than 750 percent, double that of males (Levin). The number of women in jail has climbed 1,492 percent since 1980, while the number of females in prison has risen 1,012 percent (“Incarceration Trends in Indiana”). Since 1970, the women’s number in U.S. prisons has surged 14-fold; from less than 8,000 in 1970 to almost 110,000 in 2013, and women in jail now account for roughly half of all women in the country (“Incarceration Trends in Indiana”; “Incarceration Trends in Jersey”). The growth has been driven by the rise in the incarceration of white women for property and drug-related offenses (Levin). Moreover, around seven percent of American youngsters have had a parent jailed, with black, poverty-stricken, and rural minors being disproportionately impacted.

The implications are severe, ranging from precarious housing to long-term side effects on well-being. Levin adds that according to research, children share the punishments in many aspects with their parents, including a greater risk of mental and physiological disorders, sleep problems, and poor nourishment. According to the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, parental imprisonment has contributed to roughly 20,000 children entering the state’s foster care system each year since 2016 (Levin). Women now account for about one-quarter of all prison admissions, up from less than one-tenth in 1983 (“Incarceration Trends in Indiana”). The number of women in New Jersey prisons has quadrupled (“Incarceration Trends in New Jersey”). More than sixty percent of women in state prisons, and almost eighty percent of those in jail, have little children, and the majority are the primary caregivers (Levin). Based on a 2017 analysis by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, no state imprisons more females than Texas, where four out of every five women in state prison are mothers (Levin). Consequently, the average term for a drug conviction is nine years, and more than eight years for theft charges, which is a significant amount for a kid’s growth.

The second crucial issue that needs to be addressed is the safety of imprisoned women. For instance, inmates at New Jersey’s Edna Mahan Correctional Facility, the state’s only women’s jail, claimed being assaulted while shackled (Tully). The event injured at least three women. According to a Justice Department investigation released in April, detainees at the facility were sexually molested daily by guards (Tully). Additionally, they were occasionally compelled to participate in sexual activities with other convicts while staff members looked on, a compulsion that was judged so common that it violated constitutional prohibitions against cruel and unusual punishment.

Policy Alternatives

The policy action proposed in brief is the most desirable because the problem of violence and sexual abuse remained. Several guards were sentenced for sexually abusing women in 2018 and 2019; nonetheless, women suffer from injustice (Tully). Nevertheless, because men make up the great bulk of the jailed community, the experiences of women and trans and nonbinary persons are all too frequently lost. The policy offers a reconsideration of safety measures for imprisoned women regardless of their sexual orientation and identity. Additionally, one of the proposed options is that the well-being of the incarcerated women’s children should be considered. These children frequently have psychological issues and a higher risk of joining the criminal justice system due to stress and lack of care.

Conclusion

Policy recommendations include addressing various significant issues women encounter in jail, the majority of which go unaddressed in the prison environment. First, isolation from children and significant others should be minimized to benefit the women and their children’s future well-being. Second, women are disproportionately affected by drug misuse, and there is a lack of substance abuse treatment as well as physical and mental health care (Levin). Furthermore, the safety of imprisoned women should be prioritized to guarantee that every individual is treated fairly and does not encounter any discrimination.

Recommended Sources

“Incarceration Trends in Indiana.” Vera Institute of Justice, 2019.

“Incarceration Trends in New Jersey.” Vera Institute of Justice, 2019.

Levin, Dan. “As More Mothers Fill Prisons, Children Suffer ‘A Primal Wound.’” The New York Times, 2019.

Tully, Tracey. “31 Guards Suspended at a Women’s Prison Plagued by Sexual Violence.” The New York Times, 2021.