Introduction

Language is essential to human communication and culture because it promotes social interaction, idea-sharing, and self-expression. Mexican Spanish is one of the most widely spoken minority languages in the United States, with millions of speakers domestically and abroad. Mexican Spanish’s syntactic, phonological, morphological, and orthographic structures are discussed in depth in this research paper.

Mexico is the leading country where Mexican Spanish is spoken, with several distinct dialects. However, it is also widely used in states like California, Texas, and Arizona, which have sizable populations of immigrants from Mexico. Mexican Spanish is a Spanish dialect with some similarities to other dialects spoken in Latin America, but it also has some unique characteristics.

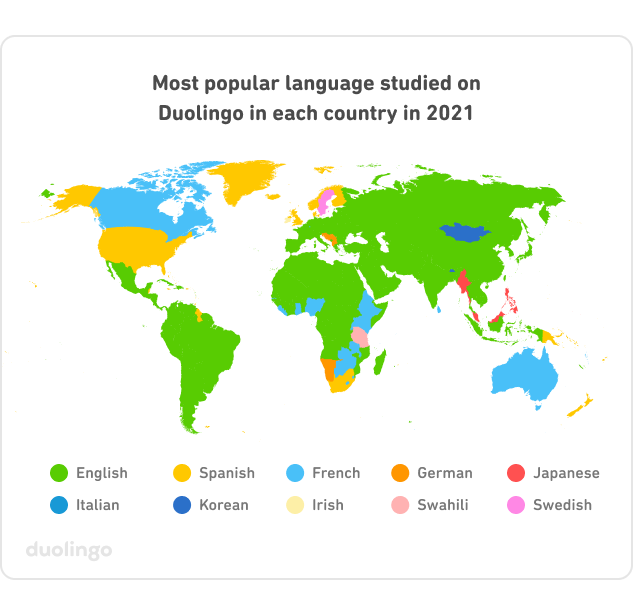

Figure 1 above shows that Spanish and English are the two most widely spoken languages in Mexico, represented by orange and green colors, respectively. The study examines Mexican Spanish’s phonemic inventory, phonotactic restrictions, syllable structure, inflectional system, morphological restrictions, and keyword formation processes. The syntactic characteristics of Mexican Spanish are also examined, including question formation, word order, and agreement requirements.

Mexican Spanish academic and everyday registers are also discussed, along with their cohesion strategies. Both the difficulties that Mexican Spanish native speakers encounter in learning English syntax and the teaching methods that would help them learn Mexican Spanish are mentioned. This research paper’s primary goal is to provide a thorough analysis of Mexican Spanish, a minority language that is vital to the country’s linguistic and cultural diversity.

Researchers hope to learn more about the language and its users through this study, including the difficulties second-language learners of English syntax face. This study aims to shed light on the distinctive characteristics of Mexican Spanish and its contributions to the rich linguistic heritage of the United States.

Background Information

Spanish, which is spoken in Mexico, has grown significantly in popularity worldwide. Mexican Spanish is one of the most widely used languages in the world, with an estimated 121 million native speakers. These people primarily speak Mexican Spanish, which is the national tongue of Mexico.

However, there are also sizable populations of Spanish-speaking Mexicans in the United States, Central America, and other countries. Mexican Spanish is the most widely used language outside of English in the United States. Although it is spoken throughout the country, the southwestern states like California, Texas, and Arizona have the highest population of speakers.

Mexican Spanish is regarded as one of the most distinctive varieties of Spanish in terms of its relationship to other varieties. It differs from dialects, including outstanding intonation and pronunciation patterns, specific vocabulary, and idiomatic expressions. Despite many similarities to other Spanish dialects, it is widely acknowledged as a unique variety with unique traits. Mexican Spanish has a complicated status as a language.

Despite being widely recognized as Mexico’s official language, many linguists believe it to be a Spanish dialect. There is an ongoing discussion about whether Mexican Spanish should be regarded as a distinct language or merely a dialect of Spanish. The distinction between language and dialect can sometimes be somewhat arbitrary. Several particular regional dialects of Spanish are spoken in Mexico, each with distinctive traits.

The Yucatec Maya dialect is spoken in the Yucatan Peninsula. The Nahuatl dialect, spoken in central Mexico, and the Chiapas Highland dialect, spoken in Chiapas, are some of the most well-known dialects. Each dialect has a unique vocabulary, pronunciation style, and grammatical conventions.

Phonological Description

The study of sounds in a language and how they are used to convey meaning is known as phonology. The phonological description of a language, including its phonemic inventory, phonotactic restrictions, and syllable structure, will be discussed in this section. Vowel shortening in the context of overall syllable lengthening may signify that phonological processes make up for reduction effects (Marchini and Ramsammy 4).

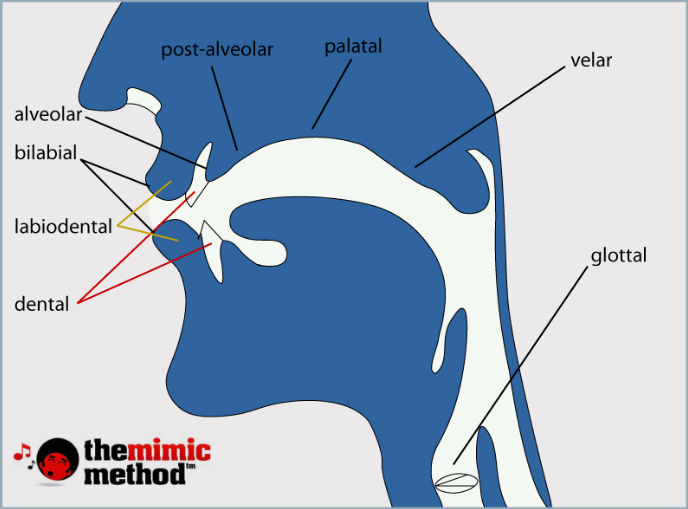

Mexican Spanish will be the focus of our Language Analysis Project (LAP) in this essay. Twenty consonants and five vowels make up the phonemic inventory of Mexican Spanish. The consonants are bilabial, dental, alveolar, palatal, velar, and glottal sounds. There are five vowels: a, e, i, o, and u. ai and au are two additional diphthongs in Mexican Spanish. Mexican Spanish is the only dialect in which the phoneme /x/ occurs.

The figure below shows the eight various parts of the mouth and throat where sounds are produced, and they affect the cadence and clarity of speech.

Phonotactic constraints are the guidelines that determine where sounds are positioned within a language. The complex cognitive process of integrating new phonological knowledge into the learner’s already-existing cognitive structure is L2 English phonological acquisition (Bouchhioua 41). Syllables in Mexican Spanish can either be open or closed. Closed syllables end in a consonant, whereas open syllables end in a vowel.

Additionally, words are frequently pronounced with a vowel between two consonants in Mexican Spanish to avoid consonant clusters. The word “tres” (three) is pronounced to avoid the consonant cluster with a slight pause between the /t/ and /r/ sounds. With a few exceptions, Mexican Spanish typically has a CV (consonant-vowel) syllable structure (Marchini and Ramsammy 4).

Mexican Spanish has a straightforward syllable structure with few consonant clusters and preferred open syllables. In Mexican Spanish, the second-to-last syllable of a word is typically where the stress is placed.

It is significant to remember that phonology can change depending on the dialect and regional variation of the speaker. Different dialects of Mexican Spanish have different phonological characteristics, such as how the phoneme /x/ is used and how some vowels are pronounced. For instance, speakers from other regions might pronounce the vowel /e/ as /ej/, while those from the Yucatan peninsula might pronounce it as /e/.

Morphological Description

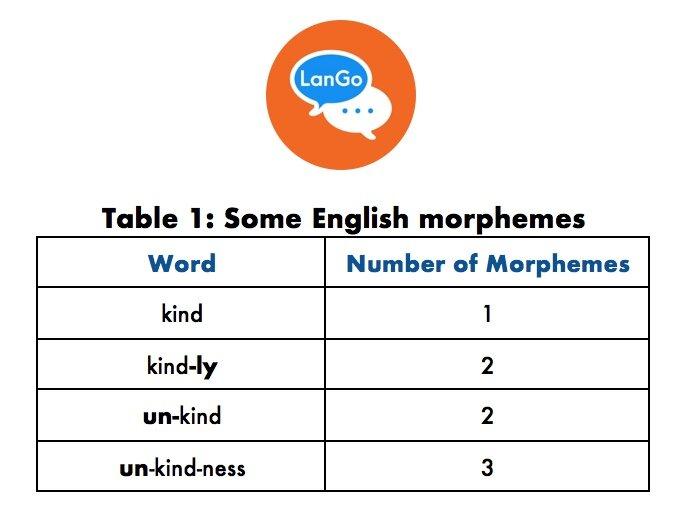

Mexican Spanish, like every other language, must have morphology. The study of morphology focuses on how words are formed using morphemes, the minor meaningful units in a language. The morphological characteristics of Mexican Spanish, such as its language type, inflectional system, morphological restrictions, overlap between morphology and phonology, and necessary word formation procedures, will be covered in detail in this section.

Mexican Spanish is an inflectional language, meaning words are changed by adding suffixes to signify grammatical meanings like tense, number, gender, and person. The two primary morphological operations in the language—inflectional and derivational—allow new words to emerge from existing ones.

Mexican Spanish uses suffixes, prefixes, and infixes as part of its inflectional system. The most prevalent inflectional morphology in Mexican Spanish is the suffix, which denotes tense, number, gender, and person. For instance, the suffix -o denotes the masculine gender of a word, while the suffix -a denotes the feminine gender.

Additionally, verbs are given suffixes like -ar, -er, and -ir at the end to denote their respective infinitive forms. By affixing prefixes and suffixes to existing words, a process known as derivational morphology produces new words. For instance, the word “hacer” (to make) becomes “deshacer” (to undo) when the prefix “des-” is added. Similar to how “amable” (friendly) becomes “amabilidad” (friendliness) when the suffix “-idad” is added.

Mexican Spanish has many morphemes; its morphology and phonology are closely related. For instance, the morpheme -o, frequently used to denote the masculine gender, is pronounced differently depending on the consonant sound that comes before it. The way a word is stressed can also alter its meaning, as seen with the words “papa” (father) and “papá” (potato), which only differ in how they are stressed.

However, Altiplateau Mexican Spanish does not have strict vowel duration uniformity between stressed and unstressed syllables (Marchini and Ramsammy 19). The use of morphemes in Mexican Spanish is also restricted. For instance, certain morphemes and suffixes cannot be used in specific grammatical contexts, respectively. Understanding these limitations is crucial for comprehending the language’s underlying structure and rules.

Finally, several essential word formation techniques are used in Mexican Spanish, including compounding, derivation, and conversion. For example, the word “cortacésped” (lawnmower), which is a compound of the verbs “corta” (cut) and “césped” (grass), combines two or more existing words to form a new one. Derivation and conversion involve adding affixes to new or existing words to alter their grammatical category. Figure 3 illustrates how morphemes are separated in a word and then counted.

Syntactic Description

A language’s sentence structure, word order, agreement requirements, and question formation are all aspects of its syntactic description. This section will examine the syntactic characteristics of the language under study. The language has a subject-verb-object (SVO) main sentence structure with minor variations (Malovrh and Lee 826).

The object may occasionally come before the subject or the verb, but this is uncommon. For instance, “Yo como una manzana” (I eat an apple) is a typical sentence structure in Spanish that adheres to the SVO pattern. To put the object before the subject, one can also say, “Una manzana yo como” (An apple I eat).

The formation of questions in the language also adheres to a set of rules. Questions are typically created by putting the verb before the subject. If one wants to ask someone in Spanish if they speak English, one will put the verb “hablas” before the subject “t.” This rule does have some exceptions, such as when the subject and verb are inverted in formal speech.

The gender and quantity of the nouns and pronouns used in a sentence determine the language’s requirements for agreement. For instance, Spanish adjectives and articles must match the gender and number of the nouns they modify. Verbs must also match the subject in both person and number. For instance, the verb “hablar” is used in the first-person singular form to match the first-person singular subject “yo” in the sentence “Yo hablo Español.”

The language under study also has deep and surface structures that can influence its syntax. The deep structure refers to the sentence’s underlying meaning, whereas the surface structure refers to the actual arrangement of words in a sentence. Due to transformations or movement rules, the surface structure occasionally differs from the deep structure.

Finally, the syntax of the language is significantly influenced by its morphology. The inflectional system and keyword formation processes can impact word order and agreement requirements in a sentence.

Mainstream Perception

The majority of Americans view languages and their speakers differently, depending on several variables. These include the socioeconomic standing of the speakers in question, political viewpoints, and cultural biases. Negative stereotypes or presumptions about the intelligence or educational level of those who speak minority languages may exist. Mexican Spanish has a complicated history of perception despite being a widely used and recognized language in the United States.

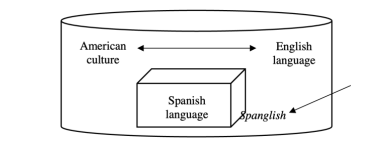

Due to the proximity of Mexico and the U.S., many Mexican Americans speak a variety of Spanish heavily influenced by English, known as “Spanglish.” Figure 4 illustrates the Spanish, which exhibits the properties of a sponge; hence, the accent and dialect are interfered with. While some traditionalists view this language mixing as a threat to the purity of the Spanish language, others celebrate it as a reflection of the cultural hybridity many Mexican Americans exhibit.

Additionally, broader perspectives on immigration and national identity may impact how the general population perceives Mexican Spanish. Recent political controversies over topics like citizenship and border control have produced a charged environment that may affect how Mexican Spanish and its speakers are perceived. Media portrayals and political rhetoric reinforce negative stereotypes and biases, which could diminish the value of the language and the people who speak it.

It is also important to remember that Mexican Spanish has a long and rich history in the United States and has been valued as a valuable cultural resource by many Americans. The language has been studied and researched in academic settings and integrated into American popular culture through music, film, and television. Despite the difficulties they might encounter, this has aided in promoting a more optimistic and inclusive view of Mexican Spanish and its speakers.

ESOL Consideration

ESOL consideration is a crucial factor when learning a language. It examines attitudes toward education, using English and native languages, easy and difficult concept identification, and transfer/interlanguage error patterns. This is the Language Analysis Project’s foundational section, connecting and expanding on sections 1 through 5.

When discussing patterns of transfer and interlanguage errors, it is crucial to remember that learners of a language frequently transfer the rules and structures of their native language to the target language. Mexican Spanish speakers learning English often make mistakes with subject-verb agreement, omit auxiliary verbs, and use the present rather than the past tense (Goldin 3050). Spanish uses auxiliary verbs less frequently than English and has a different verb conjugation system.

Mexican Spanish speakers may need help with some of the easy and challenging concepts of English syntax. For instance, because Spanish has articles in different ways from English, using the articles (a, an, and the) can be challenging. Also, English word order is more rigid than Spanish’s, which can be tricky (Ehret and Szmrecsanyi 33). In contrast, the word order in Spanish can vary more and still mean the same thing.

Attitudes toward education, English, and the use of heritage languages can also impact the acquisition and learning of English. There may occasionally be a misperception about using the heritage language, which makes people reluctant.

As a result, the learner may become discouraged or embarrassed when speaking English, which can hinder their ability to learn the language. On the other hand, a positive outlook on the native tongue can aid in learning English because it encourages code-switching between the two languages and gives a stronger foundation in language skills.

The pragmatics of English, such as understanding when and how to use words like request, apologize, or offer, may also be complex for speakers of heritage languages. They might also need help understanding idiomatic expressions and words put together to form a phrase whose meaning cannot be deduced from its constituent parts.

The complexity of English spelling and pronunciation, which can be very different from those of their heritage language, presents another challenge for speakers of heritage languages. For instance, many English vowel sounds and consonant blends are absent from speakers’ native tongues. Therefore, speakers of heritage languages may need help with spelling and pronunciation, resulting in mistakes and misunderstandings.

Attitudes toward education, in general, can also influence the success of heritage language learners in learning English. Some heritage language speakers may originate from societies that highly value education and academic achievement. Others, on the other hand, might have encountered discrimination based on their language or cultural background or a lack of access to high-quality education, resulting in unfavorable attitudes toward education and a lack of motivation to learn English.

Attitudes toward using their native tongue can also influence the success of heritage language learners in learning English. Some speakers of heritage languages might be inspired to preserve and advance their knowledge of their native tongue because they feel a sense of pride in their heritage and culture. Others, on the other hand, might believe that English is the only language that can be used for communication because they have encountered prejudice or negative attitudes toward their native tongue.

Syntactic Structure and Challenges for English Learners

Mexican Spanish’s subject-verb-object (SVO) structure predominates in declarative sentences, but subject-object-verb (SOV) structures are also occasionally used, such as in subordinate clauses. Given its relative flexibility, the word order can be changed for emphasis or stylistic reasons. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections are just a few of the word categories found in Mexican Spanish.

Adjectives frequently come before nouns because they are marked for gender (masculine or feminine) and number (singular or plural). Strong verb inflections indicate tense, aspect, mood, person, and number. Prepositions, conjunctions, and articles are frequently used to help make word connections in Mexican Spanish.

Another essential component of Mexican Spanish syntax is a subject-verb agreement, where the verb agrees with the subject in person and number. Adjectives that come before or after nouns are frequently used, and they usually match the noun they modify in terms of gender and number.

The use of conjunctions and subordinate clauses makes Mexican Spanish more recursive. Subordinate clauses can be used as adverbial or adjectival phrases and to modify nouns or verbs. Mexican Spanish sentences can be visualized as trees, with the main clause as the root and the supporting clauses as the branches. The lack of inflection in English verbs for person and number may make it difficult for native speakers of Mexican Spanish to learn English syntax.

They might also need help with English’s particular word order and article usage. Spanish from Mexico has many words in common with English, including “familia” (family) and “idea” (idea). False cognates do exist, though, such as “embarazada,” which in Mexican Spanish means “pregnant” but is frequently mistaken for the English word “embarrassed” (Kyrylyuk and Dmytryshyn 412). Languages like “chili” and “taco” that originated in Mexican Spanish have been incorporated into English.

When tutoring Mexican Spanish speakers, it is crucial to consider a student’s language background and familiarity with English syntax. Employing techniques like scaffolding, explicit grammar instruction, and using natural resources may be beneficial (Hromalik and Koszalka 542-543). Mexican Spanish used in academic contexts may have a different vocabulary and register than spoken daily. Slang and regional variations may be more prevalent in informal settings, and formal and informal registers can differ significantly.

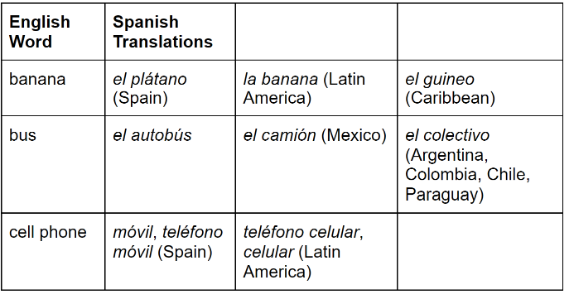

Mexican Spanish uses pronouns, repetition, and conjunctions to connect ideas and establish coherence. Teaching methods like task-based learning and communicative language teaching can benefit Mexican Spanish learning. However, translation and explicit grammar instruction may also be beneficial for English learners who are more accustomed to analytic languages. The figure below shows translations of three English words into Spanish.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Spanish spoken in Mexico is a sophisticated language with deep cultural and historical roots. The language is widely used in Mexico and other countries where people speak Spanish. Mexican Spanish has a wide range of consonants and vowels, as well as a wide range of phonotactic restrictions and syllable structures. The subject-verb-object (SVO) word order, various agreement requirements, and use of movement rules are all features of Mexican Spanish’s syntactic structure.

Mexican Spanish may have a different register in academic contexts from everyday speech. Academic writing may use less colloquial language and be more formal and precise, using more technical terms. Various instructional techniques, including immersion programs, explicit grammar instruction, and natural materials, may help students learn Mexican Spanish. However, some methods of instruction, like rote memorization and translation exercises, may fail to be successful.

Works Cited

“Place of Articulation | FREE Pronunciation E-Course | the Mimic Method.” The Mimic Method, Web.

Bouchhioua, Nadia. “Epenthesis in the Production of English Consonant Clusters by Tunisian EFL Learners.” Applied Linguistics Research Journal, 2019.

Ehret, Katharina, and Benedikt Szmrecsanyi. “Compressing Learner Language: An Information-theoretic Measure of Complexity in SLA Production Data.” Second Language Research, vol. 35, no. 1, 2019, pp. 23–45.

García-Molins, Angel López. “Multidisciplinary Reflections on Spanglish.” Estudios Del Observatorio / Observatorio Studies, 2022.

Goldin, Michele. “Language Activation in Dual Language Schools: The Development of Subject-verb Agreement in the English and Spanish of Heritage Speaker Children.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, vol. 25, no. 8, 2021, pp. 3046–67.

Hromalik, Christopher D., and Tiffany A. Koszalka. “Self-regulation of the Use of Digital Resources in an Online Language Learning Course Improves Learning Outcomes.” Distance Education, vol. 39, no. 4, 2018, pp. 528–47.

Kyrylyuk, Tanya, and Tanya Dmytryshyn. “CULTURAL DIFFERENCES AND NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION.” 2019.

Malovrh, Paul A., and James F. Lee. “What Does Explicit Knowledge Look Like? An Analysis of Information Structure in Rule Formation by L2 Learners and Its Relationship with Guided Inductive Learning.” The Modern Language Journal, 2022.

Marchini, Gilly, and Michael Ramsammy. “Vowel Compression in Altiplateau Mexican Spanish.” Isogloss, vol. 8, no. 4, 2022, pp. 1–27.

Orenstein, Sam. “The Incredible Ways Spanish Is Spoken Differently All Over the World – Wyzant Blog.” Wyzant Blog, 2021, Web.

Pajak, Bozena. “Find Out the Most Popular Language to Study in Each Country.” Duolingo Blog, Web.