The target market for Marks and Spencer is the US retail market. The selection of the country is based on the consumer demand for retail products including clothing, food, and home products. The details provided in the consumer groups section and market overview explain the reasons for selecting this market.

The US Retail Market Overview

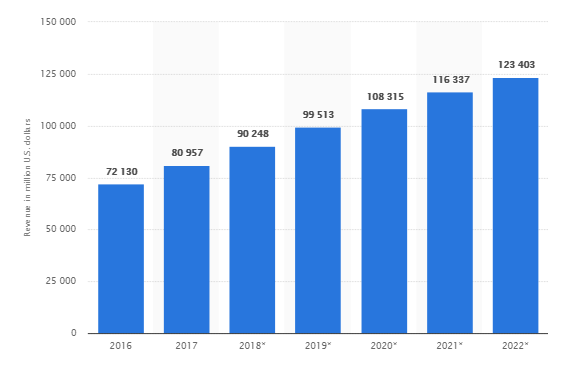

The US retail market reported an average growth of 4.5 percent in the last three decades. The statistics showed that its annual total retail sales reached $24 trillion in 2015 as compared to $22 trillion in 2014. The market is highly competitive due to the presence of US-based retailers selling their products in the local and international market. Five of the ten largest retail companies in the world are based in the US, and most of them operate in the domestic markets of the US (Farfan 2017). The trend of online shopping for apparel is also increasing in the US. Further growth is expected in the sales of apparel and accessories by e-commerce businesses, which is highlighted in Figure 1. Therefore, it could be suggested this business channel should be considered by companies in the retail sector to reach a larger market of consumers in different countries.

Gaps for Different Consumer Categories

There are three main consumer categories for Marks and Spencer in the US retail market including kids, men, and women. The primary focus of Marks and Spencer is on these three categories depending on the increasing trend of money spent on apparel and accessories. Therefore, the company will primarily target these three categories to achieve its marketing objective of higher sales of its products in the US market.

Kids

Kids are the primary target of Marks and Spencer’s apparel segment in the US. The apparel is available for boys and girls of age between 3 months and 16 years. A gap is identified in this age group as there is a consumer shift towards discounted stores for shopping. Ewen (2016) highlights the statement of Andy Mantis that Amazon recorded high sales growth in the teenage market. The statistics also showed that around half of the revenue growth from online shopping was generated by discounted-price sales offered by the US retail stores. Millennials are attracted towards discounts and packages that are marketed by companies on social media.

Marks and Spencer is also specialized in offering high-quality consumer products for teenagers. The slogan of the company is “don’t ask the price; it’s a penny,” which can be revised in this market. Although there are many domestic and international brands offering differentiated products in the US, Marks and Spencer can fill the gap by offering high quality products at affordable prices. The US kids are price conscious when it comes to shopping branded products, and they look for discount packages and off-prices to make their buying decisions. Therefore, it is important to look into this gap to achieve the marketing objective of increasing sales in the US market.

Men

The report of IBIS World (2016) indicated that the problem of obesity in the United States is increasing every year. Over 70 percent of men are overweight, and they cannot wear fashionable clothes due to their oversized body. Many retailers in the US market provide fashionable clothing to their domestic and international customers. However, there is a lack of fashionable apparel line for men who do not have a regular-shaped or sized body, which also affected the sales of retailers and departmental stores in 2016. Although there will be a small group extra-large men who prefer to wear luxury brands, it is a gap found in the US apparel industry.

Marks and Spencer offers a variety of apparel to its worldwide customers. The company can take advantage of this gap by targeting oversized men in the US. The accessibility is possible only when it is offered to them through the online store, wholesale club or departmental stores. The new brand should be communicated effectively to this group of customers. It is indicated that the US apparel market is highly competitive due to the availability of US-based and international companies. However, Marks and Spencer can gain a competitive advantage by offering high-quality fashionable clothing for men.

Women

The demand for plus-sizes is increasing in the US apparel market. The US retail chains have not paid special attention to the women in this group. Although there are few products available in this market, the large store brands have not yet realized the importance of the increasing demand for plus-size women’s clothing. A gap is found between demand and supply in the women segment as it is claimed by big-size women that they are ignored by retailers (Banjo & Molla 2016).

Marks and Spencer offers different sizes of clothing to local and international customers. The company has the opportunity to fill in the identified gap between demand and supply by offering fashionable products for overweight women at competitive prices. The strategy is required in this market segment to attract women who claim that their demands are not addressed by retailers. A clear market segmentation is also important in this case, and there is a need to spread the awareness of the availability of such products. The product differentiation is also applicable here as Marks and Spencer has to compete with domestic retailers.

Segmentation

The market research for each consumer category indicates that Marks and Spencer should not overlook the gap found in these three segments. The company plans to enter the competitive market of the US. Therefore, a strategic plan will fill all gaps to achieve the goal of competitive advantage (Williamson & Jenkins 2013). The segmentation should include a low-pricing strategy to target kids, and product differentiation should be followed based on irregular sizes for men and women clothing. There is also a need to prepare a different marketing strategy for each gap. However, the company can achieve its marketing objective by incorporating all of them in a single campaign.

Current Marketing Mix

Product

The products of Marks & Spencer are classified into many categories including clothing, food, footwear, and accessories. The category of food includes main courses, starters, and wine, etc. The clothing category includes cashmere, jumpers, jackets, suits, linen, skirt, and jeans, etc. The footwear category includes loafers, sandals, heels, pumps, and boots, etc. The accessories sold by Marks and Spencer include flowers, appliances, and gift items, etc. (Marks and Spencer 2018).

Price

The pricing strategy of Marks and Spencer is to set competitive pricing for its products. The company has its brand of clothing category available for kids, men, and women. However, the pricing is categorized by the company on the basis of the quality of its products. The company faces price competition due to online and large size retailers offering homogeneous products in the same markets. Marks and Spencer also adopted a dynamic pricing strategy for seasonal sales (Marks and Spencer 2018). The current strategy of the company is to lower the price of its old stocks for quick turnover.

Place

The products of Marks and Spencer are available in 50 countries including the UK, Spain, France, Turkey, India, and Hungary, etc. Marks and Spencer has around 1,000 stores in different cities that offer high-quality products (Marks and Spencer 2018). The company adopts a local currency strategy to maintain consistency in its prices of products sold in different countries. The main objective of the company is to make its products accessible through its stores. Moreover, Marks and Spencer also provides the option for international delivery of some products. The company’s management understands that the trend of online shopping is currently positive. Therefore, the company has also adopted this approach to increase its sales volume.

Promotion

The marketing and promotion strategy of Marks and Spencer is aligned with digital marketing and in-store strategy. The strategy of the company is to spread a common message through TV ads, print media, and social media campaigns. Marks and Spencer has its official website that contains the details of different product categories and types along with their prices. The marketing tactics of the company are also attributed to its sales strategy as it offers differentiated products at discounted prices in various seasons (Vizard 2015). Although the strategy is to sell old stocks during sales discount periods, the company earned a high revenue from this strategy every year. The special loyalty program, “Sparks” organized by Marks and Spencer offers reward points to customers, who can utilize them for shopping.

Extending Marketing Mix

Product

There is a need to categorize the company’s products into additional segments. It has been indicated that the demand for plus-size is increasing in the US market (IBIS World 2016). Therefore, the company can create a sub-category of apparel to increase its revenue by targeting customers in this target market. Marks and Spencer can achieve the objective of high market share by providing unique products in this competitive market.

The market research shows that millennials attract towards multinational brands that are accessible on social media. Marks and Spencer will adopt a similar strategy to use social sites for targeting kids and their parents. The company will offer packages and discounts to kids and enable them to buy its luxury brand at affordable prices. There is a need to introduce new fashionable products for kids. The addition of new products in the existing product line will attract new customers in the US. Furthermore, the new variety of clothing will be introduced in other emerging markets such as the Middle East, China, and India, etc.

Price

The current pricing strategy of Marks and Spencer is to set competitive prices of its products to gain a competitive advantage. There is no requirement to change the strategy, but the target market especially kids or youngsters should have complete knowledge about the product offerings of the company. Marks and Spencer will use social and electronic media to target its audiences as companies are increasingly using them in the modern competitive environment (Vizard 2015). The company will follow the same pricing strategy by highlighting its off-prices on different platforms. The communication will enable the company to achieve its goal of increasing its sales volume. Particularly, Marks and Spencer will offer discounts and packages on fresh stocks for kids to engage them.

Place

The existing strategy of Marks and Spencer is aligned with its objective to enhance the number of customers. However, there is a requirement to mainly focus on social media and e-commerce platform as the market research indicates that kids use websites for their purchases (Vizard 2015). The company will prepare social media analytics to redefine its marketing strategy and offer discounts and packages on bulk purchases. The company will have an opportunity to improve its international online sales as the trend of online shopping is not limited to the US. Furthermore, there is a need to open new stores in the US.

The market research shows that US customers find it difficult to find high-quality products at affordable prices. There are many global brands including Levis, Gap, and Dockers offering homogeneous products. Therefore, the physical existence of Marks and Spencer is also required in this competitive market to achieve its long-term objectives (Banjo & Molla 2016). However, the expansion plan will be based on the resource availability and feasibility of getting a high return on the investment in the US.

Promotion

There is a need for making changes to the current promotion strategy of Marks and Spencer. The company should redefine its target market and modify its segments according to the market research. The requirement is to incorporate the information regarding the availability of all categories and sizes of products at affordable prices. In fact, the company will follow up its loyalty program by informing that new sizes of existing products are also available to address the clothing issues faced a major proportion of US customers (Ewen 2016). The content will be prepared by marketing officials to deliver an emotional message and give awareness to the public that it has a solution for the problems of overweight people.

References

Banjo, S & Molla, R 2016, ‘Retailers ignore most of America’s women‘, Bloomberg. Web.

Ewen, L 2016, The new look of fashion: how 2016 made over apparel retail. Web.

Farfan, B 2017, 2016 US retail industry overview. Web.

IBIS World 2016, Plus-Size men’s clothing stores in the us: market research report. Web.

Marks and Spencer 2018, Annual Report 2017 – Marks and Spencer. Web.

Statista 2018, Apparel, footwear and accessories retail e-commerce revenue in the United States from 2016 to 2022 (in million U.S. dollars). Web.

Vizard, S 2015, ‘M&S invests 20% of media spend in social media as it ups focus on storytelling‘, Marketing Week. Web.

Williamson, D & Jenkins, W 2013, Strategic management and business analysis, 2nd edn, Routledge, London.