Introduction

In industrial organizations or microeconomics, market structures are normally categorized into monopoly, oligopoly, perfect competitions, and monopolistic competition based on the extent of concertation, product differentiation, and entry barriers. It is commonly depicted that when a market is seamlessly competitive, a balance is attained controlled by invisible forces, which then satisfies the Pareto efficiency (Cabal, 2017). However, if a market flops due to the presence of oligopoly, monopoly, externalities, or other market factors, the circumstance surrounding perfect conditions are interrupted, making it not to realize an effective resource allocation. From a microeconomics perspective, perfect competition is a form of market configuration in which every business is so small compared to the prevailing market conditions, making it hard to influence prices (Dean et al., 2020). Monopoly is also a market spectrum on the extreme where firms have sole domination and can change the price of a product to their favor.

Monopolistic competition can be described as a market arrangement that shows product differentiation and has fewer restrictions on exit and entry. Businesses in this industry have a common feature resembling monopoly (a distinguished product produces market power) and another characteristic bordering competitive enterprises (free will of exit and entry) (Dean et al., 2020). It is common in market-centered economies, as seen in various products such as breakfast cereal, laundry soap, and toothpaste, among others.

Contrarily, oligopoly is a form of market formation where there exist obstacles to entry, and few firms operate under such plan. It is an intriguing market organization due to the interdependency and interaction between oligopolistic firms. Therefore, it is deemed that pure competition is the highly appropriate market condition amongst all. Cartel and monopoly are judged policies and social vies for encouraging competition, such as the anti-domination act (Azar & Vives, 2018). Governments should attempt to attain perfect competition by eliminating various hurdles barring it while also desisting from unnecessary intervention. The resultant product will be free-market fundamentalism, and the pattern of deregulations and the small administration emanates from it.

Conversely, the striking element of the modern firms depicts dominance as manifested by huge corporations, challenging for the market share. For example, in Japan, the automobile sector has four leading establishments: Toyota, Mazda, Honda, and Nissan, accounting for approximately 80 percent of the total market. Oligopoly appears to be a global stylized fact within most sectors despite dedicated efforts by the government to deregulate the situation. It becomes hard to identify evidentiary material showing companies that have transited from oligopoly or monopoly to perfect competition (Cabal, 2017). It can be reasoned that the longstanding propensity of deteriorating frequency of market focus has been scarcely occurred across many markets and industries. All these factors result in suspecting the free competitive circumstance does not require a reliable situation.

The motivation behind studying this topic is that it is pervasive in the daily lives. Therefore, gaining extensive knowledge through research remains indispensable in understanding the economic factors behind their functionalities. In the prevailing market condition, monopolistically competitive marketplaces are characterized by numerous rival companies but sell different product lines (Azar & Vives, 2018). For instance, the Mall of America, situated in Minnesota, has about 24 stores selling women’s ready-to-wear apparel, such as Coldwater Creek and Ann Taylor. It also has about 50 stores selling both women’s and men’s outfits, such as Nordstrom’s, J. Crew, and Banana Republic (Cabal, 2017). Some other 14 stores trade women’s specialty sartorial such as Victoria’s Secret and Motherhood Maternity. These instances depict the monopolistically competitive environment that consumers meet in their daily lives, making it barely inescapable.

The same scenario of an imperfectly competitive market landscape occurs in oligopoly and contributes to the many aspects of human life. For instance, the commercial airline sector mostly features Airbus and Boeing, holding about 50 percent of large profitmaking aircraft in the world (Cabal, 2017). Other industries characterized by oligopolies include the United States soft drink sector, which is controlled by Pepsi and Coca-Cola. Explicitly, oligopolies manifest many hurdles to entry, making firms select pricing, output, and other factors tactically based on the resolutions of other companies in the market (Fujiwara, 2020). The paper provides extensive insights into oligopoly and monopolistic competitions while emphasizing their efficiency and sustainability relative to other market arrangements.

Review of Existing Literature

The term imperfect competition was introduced by Chamberlin and Robinson. In his elaboration of the large-group case and even a small-group instance (signifying oligopoly and monopolistic competition correspondingly), chamberlain appeared tangled about the two (Colombo & Labrecciosa, 2020). While attempting to separate these concepts of market structure, he continuously ascribed oligopoly as the cartel aspect to monopolistic rivalry. For example, he realized market dominance arises from product differentiation depicted by the steep demand curve. However, it also assumes free entry into the sector as manifested by the inclination of the company’s demand curve and its lengthy average cost arc.

The two aspects cannot co-exist since a company with surplus market control will probably have an extended and steep demand curve, which establishes a huge profit-making capability. Obstinately, competitive firms are succinctly subject to flat and low demand curves, which causes the possibility of excess potential to the minimum cost (Layton et al., 2018). Therefore, monopolistic competition shows that the presumption of free entry revokes the impact of product differentiation since it cannot offer market dominance alone to the firm (Fujiwara, 2020). Obstacles to entry, artificial or natural, are required to realize monopoly positions for each firm.

Chamberlin also appeared to be jumbled about the marketing scope of large and smallgroups. He viewed the monopolistically competitive company as vigorously advertising, while that is a characteristic of big corporations in oligopolistic sectors where extreme advertising and promotional wars lead to devastating losses for firms and society. Regarding the denunciation of excess capacity, Colombo and Labrecciosa (2020) posited that an entrepreneur would select an optimum scale for the rivaling business and not the one which can create a huge idling capacity. In their concept of monopolistically competitive company, Stiglitz and Dixit established that product diversity improved the monopolistic competition, which is an ideal market arrangement, regardless of the absence of economies of scale.

Product differentiation, trademarks, economies of scale, and patents form entry obstacles due to the information costs. Therefore, monopolistically competitive companies work under the minimal cost of information, but products still exhibit differentiated features. If the number of companies in an oligopoly industry is lowered, the type of products available to purchasers must reduce (Layton et al., 2018). A competitive business is highly likely to invent than a monopoly one since it has a lot to win (Fujiwara, 2020). The revenue of novelty and marginal benefits for monopolists is trivial, while if a similar origination is started by an opponent, it will gain more profits to levels that can drive others out of business. Therefore, a contestant has stronger inducements to innovate compared to a business with market power.

Some economists have distrust in the effectiveness of monopolistic competition. They find it suboptimal from attached costs, which include high selling prices, gigantic advertising needs, and excessive and unnecessary packaging. These iniquities seen in this type of market arrangement remain highly questioned (Layton et al., 2018). For example, the advertising approach used by the monopolistically competitive companies is modest due to budgetary constraints, while a few firms that can afford comprehensive marketing of differentiated products end up being oligopolies. Therefore, this fierce rivalry compels monopolistically competitive businesses to reduce their marketing and production costs steadily.

Cross transportation is also an accusation, but an item that a purchaser considers to be useful and different can cross boundaries to fulfill their needs. Differentiated goods shift from one place to the next through the economic theory that posits resources relocate to areas where they are highly valued (Colombo & Labrecciosa, 2020). For example, a product that appears to be excessive and unnecessary might become a valuable characteristic of monopolistically competitive goods. Some scholars have even disparaged monopolistic competition as one that lacks product standardization, thus, leading to many varieties.

The preconception labeled against monopolistic competition emanates from its very founders in the realms of industrial organization and microeconomics, Chamberlin in 1947 and Robinson in 1933. They postulated that imperfect competition generates inefficiency in economic institutions by leading to the rise of extra capacity (Fujiwara, 2020). They attached the word inefficiency to monopolistic competition since the start of the phrase, and it has remained one of the principal attributes. The market arrangement was partly criticized due to its small scope that did not offer extensive production, hence, a standardized good. The cost-economization effects combined with economies of scale in its market construction were rather stressed while also rationalizing oligopoly and monopoly on the foundation of the scale of efficiency.

Etro (2017) also argued that a grouping of the hurdles to entry that form monopolies as well as product differentiation as seen in monopolistic competition could lead to the setting of an oligopolistic environment. For example, when a regime gives a patent for discovery to a particular firm, it can lead to a monopoly. However, when the government allows patenting, for instance, four pharmaceutical firms, where each owns a drug for treating hypertension, the situation can establish an oligopolistic market. Moreover, a natural monopoly can occur if the amounts of products required in the market are only possible enough for one firm to function at the minimum as depicted in the long-run ordinary cost curve. Therefore, in such a business landscape, the market has room for just one firm to operate since small companies cannot function at a low average cost while marinating sustainability (Etro, 2017). Big firms cannot also sell their products due to the quantity dictated by the market.

The quantity demanded might also double or even triple the required volume to generate at the lowest of the average cost curve, meaning the market can also allow few oligopolistic firms. Furthermore, smaller companies would have greater costs and remain incapable of competing, while large firms would generate volumes to levels that they will not sell adequately at a profitable value. Therefore, this combination of market demands and economies of scale leads to the barrier to entry (Shambaugh et al., 2018). The product differentiation within a monopolistic competition might also contribute to the emergence of an oligopoly. Companies can require to reach some minimum size before having the ability to incur sufficiently on marketing and promotional approaches to institute a recognizable brand. For instance, the challenge in rivaling companies such as Pepsi or Coca-Cola is not because of the incapability to manufacture fizzy drinks (Shambaugh et al., 2018). However, creating a reputable brand name and successfully marketing it to levels that compete with these two firms would be a colossal task.

The Model of Monopolistic Competition

The monopolistic competition entails a type of market configuration where there is free exit and entry coupled with differentiated products, which offer every firm some level of dominance. Promotion of products falling within this market arrangement offers individual businesses exclusivity, which translates into generating a demand graph where all goods reflect descending sloping (Barkley, 2019). In this industry, the free entry shows the competition among firms, and profits tend to be near zero within the drawn-out equilibrium.

When a business in a monopolistically rival sector receives constructive economic gains, entrance will happen up to the period when pecuniary returns equate to zero (Shambaugh et al., 2018). Theoretically, the monopolistic rivalry has its demand curve facing downward since the business has a considerable extent of market power. In the long and short runs, the market power stems from product differentiation because every company generates a separate item. Its product has several close substitutes making the market power to be limited. In scenarios where market control substantially increases, purchasers will change to the competitor’s product.

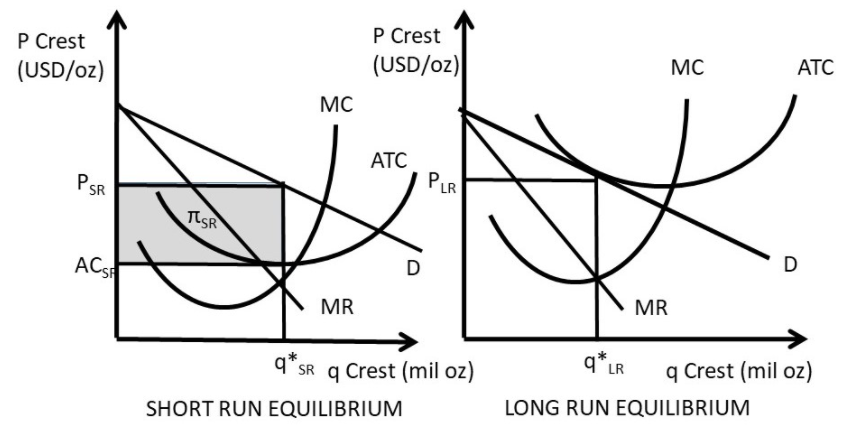

The short and long-run market structure equilibria depicted in figure 1 above have their demand curves viewing downwards, although moderately elastic owing to the existing alternatives. The momentary symmetry seems identical to normal monopoly market structure when plotted in a graph. The apparent difference is that monopolistic competition has a demand curve, which is fairly elastic. Nonetheless, the short-run equilibrium has a profit-maximizing explanation that mirrors the monopoly market arrangement. The company targets marginal income equivalent to marginal budget, which generates an output amount of q*SR (Barkley, 2019). In the above illustration, the shaded frame π shows the revenue levels.

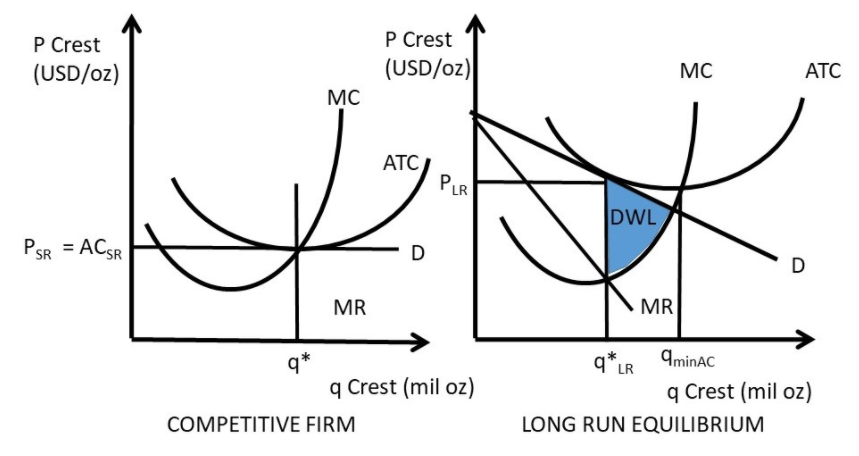

Alternatively, the long-standing equilibrium infers that the entrance of certain companies occurs up to the extent when incomes equate to zero – all costs match collected revenues. Therefore, its demand illustration is a curvature to the unvarying cost arc at the optimum extended capacity q*LR (Barkley, 2019). Furthermore, the lasting profit-optimizing number is attained when minimal income matches the negligible price. The economic efficiency in monopolistic rivalry draws two sources within its ranks, excess capacity and deadweight loss (DWL), as illustrated in figure two. The DWL arises from monopoly control when price tops marginal cost (P> MC). The market structure also exhibits surplus capacity since the steadiness value trails the minimal cost in the lowest section on the normal graph (Barkley, 2019).

The DWL caused by market supremacy instigates prices to surpass the marginal charges in the long run evenness. In figure 2 above, the price is within the long run, and the marginal cost becomes lower PLR > MC (Barkley, 2018). The situation causes the DWL to the public because the economic stability increases when P = MC. The entire deadweight loss is represented in the shaded portion in figure 2.

Another inefficiency linked to the monopolistic competition is excess capacity, a scenario where long-run quantity trails the average costs (qminAC). Consequently, a monopolistically competitive business can reduce expenses by expanding the output (Barkley, 2019). Based on the two inefficiencies linked to the monopolistic market structure, certain individuals have requested government regulations. They believe that such guidelines could be applied to eliminate or even reduce the existing inefficiencies by confiscating product differentiation, resulting in a single item rather than a large volume of close substitutes. However, government regulations might not present some viable solution to the outstanding inadequacies witnessed within monopolistic competitive arrangements due to the following reasons.

Firstly, the market dominance of a classic monopolistically rival sector tends to be minimal. In this sector, most firms produce sufficient suitable goods to provide enough rivalry to cause comparatively low amounts of control. When a business contains a lesser scope of authority, its excess capacity and DWL can be trivial. Secondly, monopolistic rivalry offers product diversity as a key advantage (Shambaugh et al., 2018). The profit drawn from product assortment might be huge since buyers can acquire quality items with diverse features. Hence, this scenario can create a situation where profits can outweigh the charge of inefficiency. The pieces of evidence supporting this assertion are witnessed in the market-centered economies where there exist massive amounts of product diversity.

Oligopoly

An oligopoly can be described as a market arrangement with few firms and has obstacles to entry. Since there are extreme amounts of competition between these few firms, they tend to make decisions on quantities, prices, and marketing to maximize the net gains (Wang & Werning, 2020). Since this kind of market arrangement has fewer companies, each business’s gains rely not just on resolutions but also anchors in other firm’s tenacities.

Regarding strategic interaction in an oligopolistic market, every firm needs to consider both other company’s responses to their decision and the individual business needs also requires reacting in a tactful manner to other firms’ resolution. Hence, there is a persistent interplay between reactions and decisions by every company in the sector (d’Aspremont & Ferreira, 2020). All oligopolies should consider embedding these strategic engagements when reaching key decisions. Moreover, since oligopolistic firms rely on strategies of other businesses, the premediated dealings form the base of its vast understanding. For instance, the market share of a vehicle manufacturing company is dependent on the quantities and price structures of businesses within this sector. For example, if Toyota reduces prices compared to other automobile manufactures, its market share will simply increase at the cost of others in the industry.

When formulating strategies for oligopolistic companies, managers normally presume their counterparts in the rival corporations are smart and rational in crafting their strategic approaches. Their tactful interactions constitute the model of game theory pioneered by John Nash. Mathematicians and economists explore Nash Equilibrium in elaborating game theory, which has become useful in oligopoly (Wang & Werning, 2020). Nash Equilibrium emphasizes outcome that lacks propensity to transformation and individual firms select strategies based on that of the rival. Therefore, in oligopoly, Nash Equilibrium deduces that individual organizations realize lucid profit-maximizing resolutions while constantly retaining the outlook of the competing firms. The assumption simplifies oligopoly theories due to the potentials for massive intricacies of strategic communications between firms.

Theoretical Application

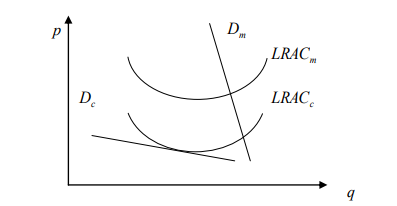

With the help of empirical analysis, the efficiency of oligopoly and monopolistic competitions can be gauged. First, the managerial slack and X-inefficiency are perhaps the most demonstrative benefit of monopolistic competition compared with other market arrangements (Etro, 2017). Due to the lack of rivalry threats and prevailing market dominance, oligopoly is subject to high managerial and administrative costs, thereby shifting the average cost of the company to the extents of LRACm as depicted in figure 3. Moreover, competitive businesses operating at low long-run with average cost curves depicted by LRACc lack X-inefficiency (Etro, 2017). The nature of inefficiency can assume various types in competitive firms such as wastage of resources, rent-seeking undertakings, managerial slacks and practices, poor coordination and organization of production, and pitiable treatment of the workforce.

Companies that fail to innovate and enhance their production technologies are likely to encounter a greater LRAC curve, leading to excess capacity. Apart from the effectiveness of management, a particular LRAC arch mirrors the extent of applied technology in the production procedures. A modest entrepreneur will be induced to regularly improve the applicable technology, reduce the average costs, and avert entry. A monopolist possesses minimal enticement to reduce his LRAC arch and use new, enhanced technology (Fujiwara, 2020). Without innovation, the firm can become inefficient by realizing excess capacity at identical levels for the demand of its products. Therefore, monopolistically competitive companies can enhance their production capacity with the key objective of preventing entry, reacting to prevailing competition by incumbents, and increase gain in the sector. Proprietors will often select technical processes and technologies, which are cost-reducing, cost-efficient, or increasing the manufacture set of the business at the corresponding scope of factor usage (Fujiwara, 2020). Faced with a reduced average cost arc, the proprietor can beat the competition using the price factor. A monopolistic competitor levies the lowest prices and generates the biggest production volume at the tiniest inefficiency possible.

Oligopoly is known for its indivisibilities, especially on aspects of production factors. Indivisibilities never allow increasing production in reaction to alteration in the market demand. Therefore, technological fads could lie at the foundation of market power because companies have to work at a bigger scale to handle indivisible elements of production. It also dictates the occurrence of new businesses in the sector (Wang & Werning, 2020). Apart from indivisibilities, economies of scale stem from considerable setup cost, fixed costs, volumetric returns, and specialized inputs. Other than the substantive setup and fixed costs, big firms are subject to considerable managerial overheads, which epitomize a share of fixed prices of the company.

Fewer or even no indivisibilities of manufacture exist within the monopolistic competition. Companies with massive scaling factors in which every element of the production is easily increased or reduced have fixed costs that are nearly non-existent in the temporal run. The start-up cost for manufacturing becomes low and facilitates entry coupled with a peak scale of production that has smaller input. Incontestable fairs, recoverable prices permit utilizing inputs in marginal manners (Jackson & Jabbie, 2019). Managerial costs, administrative overheads, advertising, and marketing are low in a monopolistically competitive company while machinery is inexpensive and the workforce tends to be unspecialized.

In differentiated trading items, monopolistic rivals are regularly moved by fashion, tastes, trends, customs, and quickly changing styles. Offering an assortment is not likely without some important variable component. Therefore, inputs such as components, ingredients, dyes, and colors are critical in producing various models, flavors, sizes, or textures. The expenses of offering diverse products are largely variable costs and product differentiation, arising from the utilization of many inputs (Kumar & Stauvermann, 2020). Flexible technology and variable inputs tend to guide the cost arrangement of most competitive firms. Large Corporations are inept at giving variable, trendy items, while small businesses are flexible in making products, such as stylish women’s wear, which resonate with the market needs (Kumar & Stauvermann, 2020). It seems variety emanates from variable instead of fixed cost. Diversity and inputs alone are unique players of monopolistic competitions at best.

Oligopoly operating standardize tools and runs recurring processes experiences tall learning curves of similar products. Singular costs of manufacturing reduce with every sequential bunch of products made. A sole proprietor may not attain economies of scale on the foundation of repetition since production procedures are unique, standardized, and are subject to transformation (Jackson & Jabbie, 2019). While oligopoly concentrates on standardization and uniformity, monopolistic competition focuses on variety. Various vital products, which people consume in the present-day originate from identical, monopolistic-based production (Hartmann, 2020). However, undeniably, several socially essential items also come from competitive industries. The monopolistically rival business provides vastly useful, valued items with big marginal utility at a moderately low price and without the extravagant influence of unwarranted publicizing (Jackson & Jabbie, 2019). As part of the marketing mix by big companies, advertising acts as a hurdle to gaining entry into the market.

Discussion

Evidence from this research reveals that monopolistically competitive industries incline to have markets where facts can be found at low prices while transactions are also consuming less time to organize fully. Since information can be received with ease, the capacity for opportunism is insignificant. Monopolistically competitive companies are real-life industries where transaction prices are optimistic, yet, marginal. The companies display themselves with robust competition, easy exit and entry, accessibility, little opportunism, and abundant information with complete certainty (Hartmann, 2020). In a positive deal costs, monopolistic competition is a true reflection of competition, while a perfect market becomes an ideal, unrealistic, and hypothetical benchmark. The monopolistic competition demonstrates best the abstractness and inconsistency of perfect competition in economic association combined with a resource distribution system.

The monopolistic competition emphasizes best the unfeasibility of perfect rivalry in life. Concurrently, other market structures, which show high market dominance gravitate around other types of market arrangements where competition is absent, have a high possibility for uncertainty and the existence of contractual opportunism (Dean et al., 2020). Information is also costly to receive, coupled with artificial or natural barriers to access. Market dominance changes to a vital factor of opportunism because it is hard for many customers to manage an unscrupulous monopolist (Azar & Vives, 2018). Alternatively, it is difficult for several suppliers to engage opportunistic monopolists. Due to market disappointment, monopoly power emanates in transactions charges where they could be low in the monopolistically rival markets or even high in oligopoly. Therefore, monopolistic competition is a true type of competition in the business world.

The growth of oligopoly models in trade perspectives has increased in recent decades with the use of game theory as well as other industrial organization offering more insights into the subject. Regarding the international trade model, oligopolistic companies would consider markets in every nation as segmented instead of being integrated (Head & Spencer, 2017). It also has features where countries represent a motive to increase domestic welfare by changing rents from multinational companies to the domestic markets through increased national profits, above-normal earnings, and higher government revenues.

When oligopoly companies in a given market agree on the volumes of product to generate and the price to fix, they try to act in a monopoly-like market. By collaborating, the oligopolistic business can decide the industry output, change the pricing structure and share the gains between them. Through acts of collusion, this caliber of oligopolistic firms can lower the industry output and set favorably high prices (Barkley, 2019). It is also possible for a group of oligopolistic businesses to collude towards creating a monopoly of output and vend products at a monopoly price, in what has become branded as a cartel. For example, in the U.S., just like many other nations, it is unlawful for businesses to conspire since it is against competitive behavior and violates the antitrust laws (Ahuja, 2019). The country has competent agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission, and Antitrust Division tasked with key mandates of averting business conspiring in the country (Head & Spencer, 2017). Cartels are official contracts on collusion since they provide evidence of possible engagement, making them rare in the business landscape. Instead, complicity is silent, where companies implicitly agree competition is bad for profits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, oligopolies and monopolistic competitions are common market structures whose role in the business environment can no longer be understated. The paper has provided extensive analysis of significant welfares of oligopoly and monopolistic competitions while emphasizing their efficacy and sustainability comparative to other market structures. Anchored in variety, innovation, and transaction overheads as the causes of inefficiency, monopolistic competition has benefits over other market arrangements exhibiting market dominion. Matched to oligopoly, the monopolistic competitive sector is more likely to embrace innovations in production processes, offer a broad range of products, and lower transaction costs. Although monopolistic competitions might lack repetition, a single proprietor can easily concentrate and experience a great learning curve in offering variety.

In addition, oligopoly is perhaps the second most widespread market arrangement. When oligopolies arise from patented inventions or leveraging on the scale of economies to make products at a low average price, they can bring substantial advantages to consumers. Explicitly, the research has demonstrated that oligopolies are regularly buffeted by considerable obstacles to entry, making existing companies earn continued profits over lengthy periods. Oligopolies also tend not to make products at their minimum average cost arcs. When they lack vigorous opposition, they might want inducements to offer innovative goods and superior quality services.

References

Ahuja, H.T. (2019). Modern microeconomics (2nd ed.). Chand Publishers.

Azar, J., & Vives, X. (2018). Oligopoly, macroeconomic performance, and competition policy (1st ed.). IESE Business School.

Barkley, A. (2019). The economics of food and agricultural markets (2nd ed.). New Prairie Press.

Cabal, M. T. (2017). Introduction to industrial organization (1st ed.). MIT Press.

Colombo, L., & Labrecciosa, P. (2020). Oligopoly: Dynamic oligopoly pricing with reference-price effects. European Journal of Operational Research, 288(2), 1006-1016. Web.

d’Aspremont, C., & Ferreira, R. D. S. (2020). Exploiting separability in a multisectoral model of oligopolistic competition. Mathematical Social Sciences, 106(1), 51-59. Web.

Dean, E., Elardo, J., Green, M., Wilson, B., & Berger, S. (2020). Principles of economics: Scarcity and social provisioning (2nd ed.). OpenStax Economics

Etro, F. (2017). Microeconomics: Research in economics and monopolistic competition. Research in Economics, 71(1), 645-649. Web.

Fujiwara, K. (2020). The effects of entry when monopolistic competition and oligopoly coexist. The BE Journal of Theoretical Economics, 1(1), 1-11. Web.

Hartmann, T. (2020). The hidden history of monopolies: How big business destroyed the American dream (1st ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Head, K., & Spencer, B. J. (2017). Oligopoly in international trade: Rise, fall and resurgence. Canadian Journal of Economics, 50(5), 1414-1444. Web.

Jackson, E. A., & Jabbie, M. (2019). Decent work and economic growth: Encyclopedia of sustainable development goals (2nd ed.). Springer.

Kumar, R. R., & Stauvermann, P. J. (2020). Economic and social sustainability: The influence of oligopolies on inequality and growth. Sustainability, 12(22), 1-23. Web.

Layton, A., Robinson, T., & Tucker, I. (2018). Economics for today (2nd ed.). Cengage.

Shambaugh, J., Nunn, R., Breitwieser, A., & Liu, P. (2018). The state of competition and dynamism: Facts about concentration, start-ups, and related policies. Hamilton Project. Web.

Wang, O., & Werning, I. (2020). Dynamic oligopoly and price stickiness (1st ed.). National Bureau of Economic Research.