Executive Summary

The focus of this paper was to investigate the impact of Saudi national culture on corporate culture. The case study focused on Novartis Corporation. The national culture in Saudi Arabia is unique and significantly different from that of many western nations. Being the origin of Islam, society is strictly governed by Shariah laws and principles. The researcher collected data from both primary and secondary sources. The findings revealed that the country’s national culture has a direct and significant impact on corporate culture. A firm can’t achieve success locally by introducing a corporate culture that contradicts the social and religious beliefs of the society.

When a firm is planning to make an entry into the local Saudi market, one of the first steps that must be taken at the planning stage is to understand the values and beliefs of the local society. Using the ICAI model and Hofstede’s theory of cultural dimensions, it is possible to learn the values of the society and their relevance in an organizational setting. A firm must understand that this society is highly patriarchal and that some practices are abhorred or prohibited by law. The study revealed that Novartis Corporation has had to adjust its operational strategies to be in line with the local Saudi culture. It has developed its unique corporate culture in line with its vision and mission. However, organizational culture is strongly entrenched in Saudi national culture to ensure that the firm achieves acceptance within the local community. The ability of a foreign firm to succeed in this market depends on its capacity to integrate the national culture into its corporate culture.

Introduction

The emerging technologies have created a global market where firms can easily operate in various countries based on their capacity to move beyond their national border. Many multinational corporations have benefitted from new technologies in the communication and transport sector. According to Azanza, Moriano, and Molero (2013), operating in the global market offers a firm an opportunity to overcome challenges in a specific market. If the economy of the United States is facing an economic recession, as was the case in 2008, a global company can benefit from a growing economy in China or other European nation. The risk that a firm faces in one country can be dealt with by benefits that a different country offers. Andersen (2013) explains that while the emerging technologies in the fields of transport and telecommunication have brought the global society together, some cultural practices are still unique to specific countries. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has a culture that is deeply entrenched in Islamic culture. The legal environment and cultural practices are significantly influenced by Islamic principles. It is significantly different from the socio-economic culture in the United States and many parts of Europe where Muslims are the minorities.

When a firm from the United States or Canada opens a new branch in Saudi Arabia, it will have to redefine its organizational culture to achieve the desired level of success. According to Notarnicola (2015), successful organizations understand the relevance of creating a corporate culture that defines the standard behavior and practices of its employees when on official duties. The top managers should be able to predict the possible decisions that their employees will take when faced with different challenges in the workplace. When developing a corporate culture, Hays-Thomas (2017) notes that it is impossible to ignore the national culture of a country when developing a firm’s corporate culture. Saudi society has principles and practices that define the socio-economic environment. It means that when a firm is developing its organizational culture, it must find a way of integrating the local culture into it to achieve success. It is important to investigate the impact of national culture on corporate culture.

Novartis Corporation is one of the leading pharmaceutical companies in Saudi Arabia (Andersson & Djeflat 2013). The company has branches in various parts of the world and it offers a variety of products to its customers. The industry where the company operates and the geographic area that it serves makes it a perfect choice when investigating the impact of national culture on corporate culture. The firm has registered impressive growth in Saudi Arabia, just like in many other countries. It means that the firm has been able to understand the local Saudi culture and integrate it into its corporate culture, making it possible to achieve massive success. Using the case study of Novartis Corporation in Saudi Arabia, this paper will investigate the impact of Saudi national culture on corporate culture. The following questions will be answered:

- How does a national culture (Hofstede six domains) impact on the results of each of six OCAI domains of actual culture results as long on its cumulative results?

- Why does a national culture (Hofstede six domains) impact on the results of each of six OCAI domains of actual culture results as long on its cumulative results?

- How this impact can be manipulated toward better corporate culture?

Literature Review

The previous chapter provided background information and the focus of this study. In this chapter, the focus was to review what other scholars have found out in this field. The impact of national culture on corporate culture is an area of study that has attracted the attention of many scholars over the recent past. Mor-Barak (2014) explains that it has become increasingly evident that the local culture influences how firms conduct their business. In this section of the paper, the focus was to review the findings that have been made by other scholars on this and related topics. As Holz (2016) notes, the goal of any given study is to come up with new information based on the identified research gaps. It is not advisable to duplicate the existing knowledge because it will not make sense in that field of study. The only way of identifying gaps in the existing body of knowledge is to conduct a review of the literature. It makes it possible to develop a basis upon which this paper was developed. Some scholars have developed theories, concepts, and tools for analyzing cultural influences on a business entity. In this study, the researcher will focus on Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (ICAI) and Hofstede’s Theory of Cultural Dimensions as some of the tools and concepts that explain this phenomenon.

Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI)

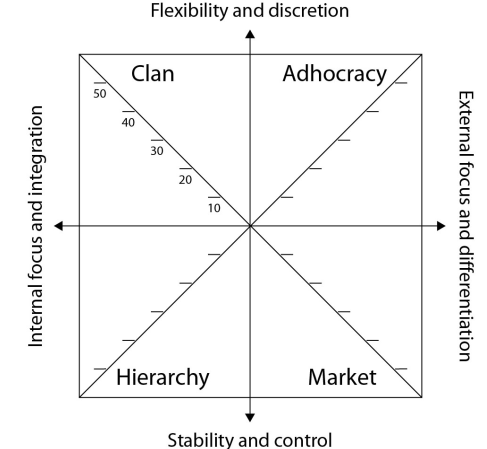

Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn developed ICAI as a method that facilitates the assessment of organizational culture (Campbell & Göritz 2014). Every organization has its unique culture that defines how junior employees relate with the top management unit and among their peers. The culture defines how every stakeholder is expected to address a given issue within his or her area of jurisdiction. The two scholars developed the framework to define different angles that organizational culture can take based on some factors. The framework identifies four types of organizational cultures based on different competing values. Laroche and Yang (2014) explain that many organizations have embraced this model, especially when they realize that there is a need to change from one approach of operation to another. Figure one below shows the framework.

The framework identifies four competing values. They include the flexibility and discretion that a firm embraces. The stability and control that a firm desire is another value. The third one is the internal focus and integration. The last category of desirable values in an organization is external focus and differentiation. Each of the four is important, but sometimes they are competing in nature. A firm must define what it desires based on the four factors when defining its corporate culture. Depending on the choices that a firm makes, one can have any of the four types of organizational culture (clan, adhocracy, market, or hierarchy) (Sheldon & Daniele 2017). It is necessary to analyze each of the four factors.

The clan culture

The clan culture is one that promotes a social working environment. Zolait (2013) says that it thrives in a workplace where stakeholders have a lot in common. The firm is viewed as one big family where the leaders are considered facilitators, team builders, and mentors. The employees and the management unit share a common tradition and social morals. This culture emphasizes the need to have teamwork, effective communication, and a close commitment to the clients (Bryman & Bell 2015). An open communication system where top managers can engage with junior employees directly is also encouraged in this model. Ozbilgin (2015) observes that the clan culture model can only work in a small entity that operates within the borders of a given country. Its emphasis on shared traditions and open communications means that it cannot be applied in large companies that operate in different countries. Of the four values identified in the ICAI model, this culture embraces internal focus and integration and flexibility and discretion. Such organizations, because of their small size, value integration as a way of improving employees’ output. They are also very flexible in their operations. They typically employ less than 50 workers, as Wang and Rafiq (2014) observe.

The adhocracy culture

This culture embraces creativity and innovation within the workplace environment. According to Tan and Perleth (2015), adhocracy culture shifts from bureaucratic approaches of management where strict rules and regulations have to be followed to one that encourages experimenting and risk-taking. They focus on long-term goals by trying new and more effective methods of achieving success. A leader is viewed as an inventor, visionary, and entrepreneur in such organizations. They create room for the junior employees to try new approaches to undertaking their duties based on emerging trends and technologies. Leaders understand that mistakes are common when trying new strategies. Workers are encouraged to use their newly acquired skills to improve their performance in the workplace. This culture can work both in large and small entities. In the ICAI framework above, it embraces flexibility and discretion and extraneous focus and differentiation as its main values.

The market culture

The market culture is a goal-oriented and competition-based culture that focuses on achieving specific goals. Chin and Trimble (2014) explain that when using this culture, a firm’s main interest is to get things done within the right time and in the right manner. Leaders are viewed as hard drivers who focus on competition, effective production and product delivery, and efficiency in the normal operations of a firm. For such firms, success and reputation are the critical factors that are cherished by the top management unit. To achieve success in a competitive market, such companies focus on lowering the cost of production to enable them to charge competitive prices. These are typically large organizations that can hire hundreds of thousands of employees. Employees are expected to work under strict organizational policies and any major deviation should be approved by the top management unit.

The hierarchy culture

The hierarchy culture promotes a structured and formalized work environment. Employees and management units are expected to work under strict and specific instructions. Formal rules are developed to ensure that actions taken by all stakeholders are based on standard practices. Such firms value stability and smooth execution of tasks (Marschan-Piekkari, Welch & Welch 2014). Leaders are viewed as organizers, coordinators, and monitors. Instructions flow from top to bottom and back based on the principles set by the top management unit. Critical values highly cherished in this concept include efficiency, consistency, uniformity, and timeliness (Parhizgar 2013). When a plan is developed, every stakeholder is expected to stick to specific roles assigned to them, and discipline is an important factor that everyone must observe.

Hofstede’s Theory of Cultural Dimensions

Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory offers a perfect description of the effect of a society’s culture on the values embraced by its members (Triana 2017). In the United States, society is embracing social practices such as homosexuality because of the liberation that has been witnessed over the past decades (Schellwies 2015). However, such a practice is abhorred in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and many other Islamic countries. Bolman and Deal (2017) explain that what a national culture value defines the practices that its people embrace. Making a radical shift from a national culture may be a terrible mistake for any company keen on achieving success. Salumificio Fratelli Beretta is one of the largest processed meat companies in Italy. One of its main produces is pork. As this theory holds, the Islamic culture that is dominant in Saudi Arabia restricts people from taking pork. As such, in the case of Salumificio Fratelli Beretta is interested in making an entry into the local Saudi market, the theory advises that it must find a different product that the locals find acceptable. The theory identifies six cultural dimensions. They include the following:

Power distance index (PDI)

The dimension explains the issue of inequality and the distribution of power in society. In some cultures, people believe that those born in royal families will always remain in power. On the other hand, those in the lower caste do not expect to rise to higher ranks. Everyone seems content with his or her social status in environments with a high degree of power index. They do not question the authority and those in lower ranks do not expect to climb the career ladder through continual improvement and empowerment. A person hired as a secretary expects to work in that position until the time of retirement. Molinsky (2013) explains that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is one of the countries with high power index, while the United States has a low power index. People tend to question and challenge authority when the degree of the power index is low.

Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV)

The dimension looks at the degree to which people in a given society are integrated (Gooderham, Grøogaard & Nordhaug 2013). Collectivism embraces a tightly-knit society where people tend to act as one big family. There are loyalty and commitment to supporting one another within a given group as a means of achieving organizational success. On the other hand, individualism is an environment where people focus on personal success. Duties may force different people to work as a unit, but everyone has specific individualistic goals that have to be realized. In such organizations, competition is stiff as every employee seeks to achieve career success. Individualism is a more popular culture in most of the western countries while collectivism is common in parts of Asia and Africa (Earley & Mosakowski 2016).

Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI)

The dimension defines the degree to which a given culture can tolerate uncertainty. Some societies value the ability to predict the outcome of a given path. They try to avoid strategies and methods whose outcome is ambiguous. They want to know what a given investment would yield after a specific period. On the other hand, some cultures can withstand uncertainties. They can embrace new methods even when it is not clear how the outcome will be after a given period. Organizations that have low uncertainty avoidance index tend to be more innovative. They can experiment with different production strategies as long as there is a likelihood of achieving the desired goals.

Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS)

The dimension measures a culture based on its preference for competition, materialism, and achievement versus preference for teamwork, empathy, and harmony. Masculinity defines culture where people value competition and materialism. People are considered successful based on what they have achieved based on material gains. On the other hand, femininity embraces teamwork both at work and in a social setting. People view success as a shared virtue that cannot depend on the effort of a single individual. As such, teamwork is highly cherished. Empathy and harmony are attributes that people who embrace this culture are expected to exhibit in their actions.

Long-term orientation vs. short-term orientation (LTO)

A culture can be described as long-term or short-term oriented. Long-term oriented culture is based on customers and tradition and in most cases is resistant to change (Bertrams et al. 2013). They emphasize the need to achieve long-term success based on standard practices that society considers acceptable. On the other hand, short-term orientation focuses on short-term goals set gradually to achieve a given target. It views change as an inevitable eventuality that must be embraced to achieve the desired goal (Yip & McKern 2016).

Indulgence vs. restraint (IND)

A society can embrace an indulgence or restraint culture. According to Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (2014), a restraint culture takes a pessimist angle where people try to avoid the negative consequences of overindulgence by having strict morals and social rules that must be followed. On the other hand, a culture that embraces indulgence allows people to explore their desires as long as they do not affect other people. Social rules and are more relaxed and people are allowed to enjoy leisure time exploring what they find to be gratifying to them (Stahl et al. 2016).

Methodology

The previous chapter has provided a detailed review of the relevant literature that provided background information for the paper. In this chapter, the focus was to define the method used in collecting and analyzing primary data collected from the participants. Data used in this paper came from two sources. The first was the secondary data obtained from books, journal articles, and reliable online sources. The second was the primary data obtained from a sample of participants. It is necessary to explain how data was obtained from the participants and the method taken to conduct the analysis.

Sampling and Sample Size

The impact of national culture in Saudi Arabia on corporate culture is a factor that affects numerous firms in the country. The impact is more pronounced in foreign firms that come to the country as a way of exploring a new market. They are met with culture shock as they have to adjust their organizational culture to be in line with that of the national culture (Bernard 2013). Data can be collected from numerous companies, especially foreign firms. When investigating an issue that affects numerous firms, it is possible to collect data from numerous respondents. However, Fisher (2010) advises that it is prudent to have several participants from who data can be obtained within the time available for the study. It means that sampling is necessary to ensure that those who are identified to participate in the study can be interviewed within the time available for the research. Novartis Corporation was identified to be the firm from which data had to be collected. Judgmental sampling method was used to identify individuals in management and non-managerial positions to take part in the study. Fifty participants (40 employees and 10 managers) were selected to be part of the study.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data was collected from the participants through interviews. Fowler (2013) explains that interviews offer the best opportunity for a researcher to collect reliable data from respondents. The physical interaction between the interviewer and interviewee increases the chances of obtaining true answers to the questions set. Many people often find it easy to lie when they are given time to think for a long time before answering questions. However, face-to-face interviews require an immediate response, which means that participants tend to be truthful in such processes. A questionnaire was developed to help in the process of collecting data from the participants. The document helped in standardizing the pattern of questioning respondents. Data were analyzed using mixed methods. It was necessary to analyze the data qualitatively to understand the nature of the impact of national culture on corporate culture. This method of analysis also made it possible to explain how foreign firms can adapt to the national culture. On the other hand, the quantitative analysis made it possible to determine the magnitude of the impact.

Ethical Considerations

When conducting research, Picardi and Masick (2013) argue that it is important to observe ethical concerns. One of the most important ethical requirements when planning to collect data from an organization is to get the approval of the relevant authorities (Nestor & Schutt 2014). In this study, data had to be collected from the employees of Novartis Corporation. As such, the first step was to get the approval of the management before contacting the employees. The relevance of the study was explained to them. Participants were selected voluntarily. No one was coerced to be part of this investigation. Employees who accepted to be part of the study had to be protected by hiding their identity. Instead of using their actual names, they were assigned codes that made it impossible for anyone to identify them. This was necessary to protect them from any form of victimization.

Analysis and Results

After collecting primary data from the respondents, the next step as Rovai, Baker, and Ponton (2013) note, is to analyze to understand the impact of Saudi national culture on corporate culture. As explained in the previous chapter, primary data was collected from managers and employees of Novartis Corporation in Saudi Arabia. The company is one of the leading pharmaceutical companies that offer a wide range of products, including oncology. It operates in different parts of the world hence its management can compare and contrast the local culture with that of other countries around the world. They can explain how the country’s culture influences their corporate culture and what the firm is doing to adapt. Junior employees were also in a better position to explain how the local Saudi culture influences how they work in this company. The responses obtained from participants were analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively.

What are some of the specific local cultural practices in Saudi Arabia that define corporate culture in an organizational setting?

This question focused directly on specific local cultural practices in the country that define corporate culture in the selected organization. The question was analyzed qualitatively. Different participants answered the question differently. Q-IBM said, “Separation between the male and female area in college and any public setting reflected as well in separation in Novartis business office that hinders smooth communication.” The respondent identified one of the common cultural practices that hinder effective integration in the workplace. During the early period of development, until one reaches college, society emphasizes the need for boys to limit their interaction with girls. When these people come from college, they find it easy to integrate (Adeline & Wai 2013).

Effective communication and engagement between male employees and female colleagues become a problem in the workplace because of socio-cultural practices. The respondent also felt that society often prefer stability over creativity. Q-IBM said, “Saudi population look usually for stability, avoiding risk and minimizing the stress that let them look for a governmental job more than the private sector, this forces the private sector to look for a foreign employee who can tolerate stress and workload than Saudi employee.” The desire for stability makes most of the Saudi nationals to prefer working in Public firms where they are assured of job security. They also do not work under a lot of pressure (Azevedo 2013). They view private firms as entities that can collapse at any time when competition or other market forces become unfavorable. They also fear the kind of workload that is common in private entities. It means that Saudi culture tends to favor public entities in terms of having access to local talents.

How has the Saudi national culture impacted the corporate culture at your current organization?

It was also necessary to determine how the local culture affects the corporate culture at the firm where the respondents work. It was easier for the non-Saudi employees to identify the impact than the Saudi nationals because they have experience of living away from the country. Q-FOQ said, “Uncertainty avoidance in national culture with the fear to speak up is often reflected in the organization. Saudization means normalization (rights for Saudi but it should be done incrementally, people avoid nepotism cause positive healthy culture).” Society has respect for authority and leaders are rarely questioned by their junior officers.

This cultural practice is often reflected in the national culture. Top managers are rarely questioned by junior officers even when there is a need to do that. Q-FOQ also noted, “Petroleum wealth exaggeration culture and global concept about Saudi Arabia market creates a scenario where the head office still demands rapid growth in a manner which has not been witnessed before.” The misconception that Saudi society is enriched by oil wealth creates high expectations for foreign firms coming to the country, according to some of the respondents interviewed. When they realize that their brand is not growing as rapidly in the local market as they desired, they get frustrated (Baack, Harris & Baack 2013). They start pushing their employees beyond the limits and even blame the local culture and other forces for the below expectation growth. Sometimes foreign firms have so high expectations that cannot be realized and the frustrations that result makes them feel that the local culture is harsh for them.

How can your organization align its corporate culture with that of the national culture within the country?

The Saudi national culture is unique, as Wróblewski (2017) observes. It is the responsibility of the foreign firms to find ways of aligning their operations and organizational culture with the local forces. When asked how this firm can achieve that feat, the respondents provided different answers. Q-RAN simply stated, “Empower more female in decision making positions.” This respondent felt that the current problem is partly caused by a cultural practice where women are viewed as being inferior to men. According to Maktoum (2017), until recently, women in Saudi Arabia were not allowed to drive because of a culture that considered them less sophisticated hence more likely to cause an accident. Many restrictions were also placed on women, making them practically answerable to men in almost every socio-economic context (Tate 2015). Many of them are raised knowing that they cannot be leaders in society. When foreign firms hire employees, they often want to offer them promotions based on their natural talents, skills, and experience. Some may find it necessary for promoting women into senior managerial positions (James 2017). However, the respondent above felt that it may not be easy for such a woman to acquire a top managerial position if the traditional culture is still embraced.

Given that the country is becoming more liberal and it is no longer a crime to assign a woman a top leadership position over men, it is up to these firms to find ways of empowering women (Ballantyne & Packer 2013). They should be made to feel that they can be leaders and that sometimes they do not have to consult men when making the right decision. Ali and Park (2016) observe that it is often necessary for the top managers to consult junior officers when making decisions. However, that manager should remember that the final decision should be one approved by them (Dawson & Andriopoulos 2014).

It means that in some cases they have to overrule the decision or advice given by the junior officers. In a society where women are taught to strictly follow the guidance of men when making critical decisions, it may take a while to have powerful female employees who can guide men to success without feeling intimidated (Darvish & Nazari 2013). As the respondent advised, it may require proper training of these employees to ensure that they are empowered (Zeiser 2015). Men should also go through similar training to make them know that they can be led by women. They should not feel intimidated when they find themselves in positions where they have to receive instructions from female managers or supervisors. The company should create a culture where people are judged based on their capacity and character, not gender (Colombo 2014).

As a non-management employee, to what does extent national culture in Saudi Arabia exerts an impact on corporate culture using Hofstede and OCAI model?

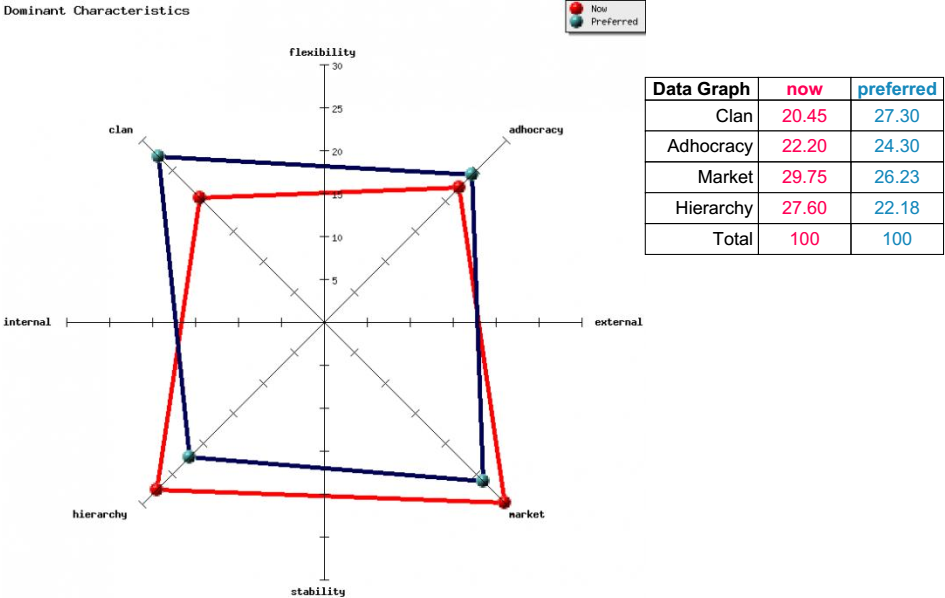

Using the ICAI model, it is possible to determine the extent to which the national culture in Saudi Arabia exerts an impact on corporate culture (Tracy 2013). The same question was posed to non-management employees and those in various managerial positions. It was necessary to determine how they would reply to this question. Q-FAD said, “Impact clan culture by 20% and market culture by 90%, Adhocracy by 60% hierarchy by 20%.” The employee felt that the culture is more inclined to market culture than it does clan culture (Moran 2015). They feel that most firms are goal-oriented and focus on achieving success, giving little priority to the clan culture that emphasizes the need to have a social environment where workers view themselves as members of a larger family (Blythe 2013). The quantitative analysis of the data obtained from the respondents revealed that this feeling expressed by Q-FAD is shared among the non-managerial employees. They have a feeling that society is shifting from the clan culture to market culture where the focus is on the ability to succeed and outsmart competitors. Figure 2 below shows that these respondents feel there is a need to move towards a clan culture and slightly away from market culture. They feel that society is fast losing family ties in pursuit of economic success.

As a manager in your current organization, to what extent does national culture in Saudi Arabia exerts an impact on corporate culture using Hofstede and OCAI model?

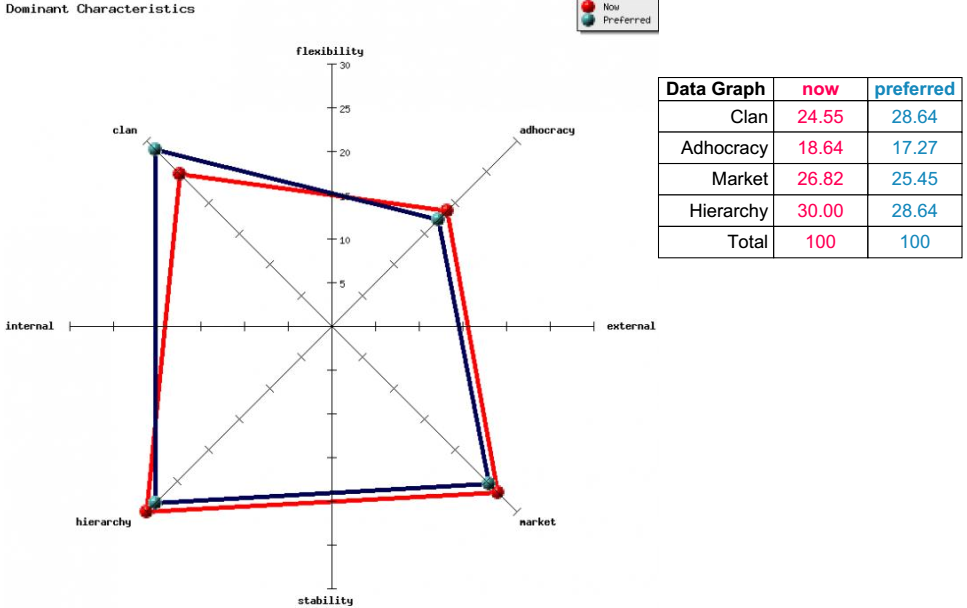

The same question was posed to those in managerial positions at Novartis Corporation. It was necessary to determine if they share the same views as junior employees of this company (Yanow & Schwartz-Shea 2014). Both managers and junior employees feel that the local culture is significantly shifting towards market culture. The only difference is that those in management feel that only a slight movement towards can culture is needed, while non-managerial employees feel there is a need for a significant movement. Q-HHH stated, “It affects Clan culture by 20% only and market culture to a great extent by 80% and adhocracy culture to 50% and no impact on hierarchy culture.” According to this manager, and many others in a similar position, there is almost a near balance between hierarchy and adhocracy culture in the society. It means that the management is comfortable with the local culture that gives them the power to exert their authority over junior employees, as shown in figure 3 below. However, those in non-managerial positions had a different view, as shown in figure 2 above. They feel that society should make a significant move away from hierarchy culture to adhocracy where they can be granted more freedom to share their views (Gbadamosi, Bathgate & Nwankwo 2013).

How can foreign firms entering the country for the first time adopt to the local Saudi culture?

The researcher also inquired from the respondents how foreign firms coming to the country can deal with the issue of cultural challenges when coming to the country. As Clark (2013) notes, Saudi Arabia is one of the attractive investment destinations for foreign firms being the leading economy in the region. However, the local culture continues to be a challenge to some of these companies. When asked this question, respondents provided varying views. Q-MGD stated “Planning and look for expertise is the best approach of addressing the problem.” The respondent felt that before making an entry into the country, a firm should have a proper plan on how to deal with the expected challenges in the market. It is also necessary for such a firm to hire talented workers capable of dealing with cultural forces in the local market (Heesen 2015).

Discussion and Conclusion

Saudi Arabia is one of the leading economies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. It is one of the top destinations for firms wishing to spread their operations to the region (Cokley, Awosogba & Taylor 2014). However, cultural factors have been considered a major hindrance to some of the foreign firms, especially those coming from western countries. The analysis of primary data and the review of the existing literature show that foreign firms need to understand the Saudi local culture when planning to make an entry into the market. In this section, the researcher will discuss the local culture in the country and how firms can deal with it to achieve the desired goals.

The Saudi National Culture

According to Cooper and Norcross (2016), Saudi Arabia is largely considered the birthplace of the Islamic religion. The holiest cities of Mecca and Medina are all found in the country (Ehde, Dillworth & Turner 2014). While many neighboring countries such as the United Arab Emirates have been influenced by the western culture due to massive immigration, Brigham and Houston (2016) note that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is still largely influenced by Islamic principles and practices. Some of these cultural practices are of great significance to a firm’s operation in a country. According to Baptista and Oliveira (2015), society in Saudi Arabia is highly patriarchal (Knight 2013).

Cultural practices and beliefs limit the ability of women to make critical decisions without consulting men. One of the restrictive cultures that have received wide criticism over the years is the need for a woman to consult and get permission from her husband, her father, or even her son when planning to travel out of the country (Ebert et al. 2015). When permission is denied, she cannot travel as enshrined in the laws of the country based on national culture. The principle is based on the belief that women cannot make independent decisions. Bratton and Gold (2017) explain that society has often believed that women tend to make decisions based on their emotions other than facts. It means that they are more likely to make mistakes in their decisions than men (Ren & Zhai 2014). As such, they need to be guided when making critical decisions.

The Saudi national culture is deeply entrenched in Islamic teachings. Leadership is believed to be a calling from God. Those who are in a position of leadership are considered to be authorities that have near-absolute power (Groh et al. 2017). The belief has created a near caste system in Saudi society. Members of the royal family are considered undisputed leaders in the country. Many people do not believe that they can climb to positions of leadership through education and entrepreneurship in this society (Pachankis et al. 2015). In many social settings, those who find themselves in positions of leadership enjoy a lot of power because people are not used to questioning authority. Clinard (2015) explains that many people grew up learning how to respect those in positions of power. The teachings of the Quran also define what people should eat and how one should relate to others. It prohibits taking food classified as unholy such as pork. At the same time, marriage is strictly limited to that between a man and a woman (Guirdham & Guirdham 2017). The freedom that is common in most of the western countries where men can marry men or women marrying women is abhorred in this society and such attempts may lead to serious punishment. Everyone is expected to act within the legal and cultural confines (Hartmann & Vachon 2017). Even when the state may be slow in issuing punishment to such practices considered social evil in the society because of international pressure, members of the society may not hesitate to take action when they feel it is necessary.

Effect of the National Culture on Corporate Culture

Cultural practices in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, some of which have been entrenched into the legal framework of the country, have a direct effect on the corporate culture that a firm develops. According to Hong and Lee (2014), it is impossible to ignore some of the Islamic principles when operating in this country. For a long time, many foreign companies were forced to avoid appointing female employees to top managerial positions because of the local culture that considers men as superior to women (Pantouvakis & Bouranta 2017). It was difficult having women steering men towards a position of success. Hanzlick (2015) also explains that in the past, many women never pursued careers in technical fields. Majority of the college graduates considered teaching and nursing as feminine careers suitable for them (Park et al. 2013). As such, corporate firms could not find suitable candidates to be in managerial positions. Aligning corporate culture with national culture, which in this case having men in a position of leadership instead of women, made things easy for foreign firms. It was considered the easiest way of adapting to the local market forces. It is culturally sound for a man to issue instructions that must be followed by everyone.

According to Sarea and Hanefah (2013), many western companies, especially those from North America, have embraced the open policy of managing human resources. It means that junior employees can easily engage with managers whenever it is necessary. They are also allowed to criticize decisions made by those in top leadership positions. However, Saudi culture does not allow such practices. The decision of a leader must be followed without questions. A firm coming into this local market must find a way of adjusting to these national practices. Holbeche (2017) explains that although a firm may want to create such freedoms in their new branch in the country, the local culture does not permit it. Most of the employees grew up learning how to follow the law and regulations strictly (Ratten, Braga & Marques 2017). It means that they may not know how to make positive criticism that can enhance the growth of a firm. Creating an environment where such criticisms are allowed may be counterproductive. A firm must learn how to operate in line with local practices.

As explained above, Islamic principles strictly limit what society can eat, especially those who are Muslims (Prescott 2016). Having a pork company in Riyadh, Mecca, or Medina can be a counterproductive investment decision. Even if a firm establishes that there is a growing demand, society does not allow such businesses. Finding people to work in such a company may be a big challenge (Yu et al. 2013). The society can easily lynch such individuals because they view it as an abuse to their religion. The company cannot be spared either. It is also important to note that society does not tolerate same-sex marriage. Otley (2016) explains that having a confessed gay known to be cohabiting with a person of the same gender as husband and wife is not advisable in the country. The practice is punishable by death. When the state fails to take appropriate action as demanded by Shariah, members of the society may take the law into their hands (Saunders & Lewis 2017). Such people can be stoned to death. A foreign firm must carefully select its executives sent to this country based on their sexual orientation to ensure that they are safe.

Conclusion

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is one of the fastest developing economies in the MENA region. The country has been attracting foreign investors from Europe, North America, and the Far East. However, the study reveals that one of the biggest challenges that these foreign firms face is culture shock. The national culture in the country is strictly defined by Islamic teachings and principles. Novartis Corporation, a giant pharmaceutical company that also offers oncology services, made a successful entry into the country. It is evident, based on data collected from its employees and managers that the company had to redefine its corporate culture to be in line with the national culture. A firm cannot afford to ignore values and beliefs popular within a country when developing organizational culture. As shown in the paper, a firm is part of the society in which it operates. For such an entity to gain acceptance within the society, it must behave in the exact manner members of the society do. Any deviation may have serious negative consequences. While the country remains an attractive investment destination to foreign companies, the study strongly recommends that foreign firms must first understand the local culture and embrace it before starting official operations.

Reference List

Adeline, K & Wai, T 2013, ‘Exploring consumers’ attitudes, and behaviours toward online hotel room reservations’, American Journal of Economics, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 6-11.

Ali, M & Park, K 2016, ‘The mediating role of an innovative culture in the relationship between absorptive capacity and technical and non-technical innovation’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 1669-166.

Andersen, T 2013, Short introduction to strategic management, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Andersson, T & Djeflat, A (eds.) 2013, The real issues of the Middle East and the Arab Spring: addressing research, innovation and entrepreneurship, Springer, New York, NY.

Azanza, G, Moriano, A & Molero, F 2013, ‘Authentic leadership and organisational culture as drivers of employees’ job satisfaction’, Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, vol. 29, no. 21, pp. 45-50.

Azevedo, A 2013, Advances in sustainable and competitive manufacturing systems, Springer, Cham.

Baack, D, Harris, E & Baack, D 2013, International marketing, SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Ballantyne, R & Packer, J 2013, International handbook on ecotourism, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

Baptista, G & Oliveira, T 2015 ‘Understanding mobile banking: the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology combined with cultural moderators’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 50, no. 9, pp. 418-430.

Bernard, H 2013, Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches, 2nd edn, SAGE Publications, Los Angeles, CA.

Bertrams, K, Coupain, N, Homburg, E, Kurgan-van, H & Mioche, P 2013, Solvay: history of a multinational family firm, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Blythe, J 2013, Principles and practice of marketing, John Wiley & Sons Publishers, Hoboken, NJ.

Bolman, L & Deal, T 2017, Reframing organisations: artistry, choice and leadership, Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Hoboken, NJ.

Bratton, J & Gold, J 2017, Human resource management: theory and practice, 6th edn, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Brigham, B & Houston, J 2016, Fundamentals of financial management, 14th edn, Cengage Learning, New York, NY.

Bryman, A & Bell, E 2015, Business research methods, 4th edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Campbell, JL & Göritz, A 2014, ‘Culture corrupts, a qualitative study of organisational culture in corrupt organisations’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 291-311.

Chin, L & Trimble, J 2014, Diversity and leadership, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Clark, D 2013, Transforming the culture of dying: the work of the project on death in America, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Clinard, M 2015, Sociology of deviant behaviour, 15th edn, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Cokley, K, Awosogba, O & Taylor, D 2014, ‘A 12-year content analysis: implications for the field of Black psychology’, Journal of Black Psychology, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 215-238.

Colombo, S 2014, Bridging the Gulf: EU-GCC relations at a crossroads, Edizioni Nuova, London.

Cooper, M & Norcross, J 2016, ‘A brief, multidimensional measure of clients’ therapy preferences: the cooper-Norcross inventory of preferences’, International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 87-98.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A, Inkpen, A, Musacchio, A & Ramaswamy, K 2014, ‘Governments as owners: state-owned multinational companies’, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 919–942.

Darvish, H & Nazari, E 2013, ‘Organisational learning culture – the missing link between innovative culture and innovations, case study: Saderat Bank of Iran’, Economic Insights, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-6.

Dawson, P & Andriopoulos, C 2014, Managing change, creativity, & innovation, SAGE Publications Ltd, London.

Earley, C & Mosakowski, E 2016, HBR’s 10 must reads on managing across cultures, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA.

Ebert, D, Zarski, A, Christensen, H, Stikkelbroek, Y, Cuijpers, P, Berking, M & Riper, H 2015, ‘Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled outcome trials’, PLOS, vol. 10, no. 13, pp. 1-15.

Ehde, D, Dillworth, M & Turner, J 2014, ‘Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research’, American Psychologist, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 153-66.

Fisher, C 2010, Researching and writing a dissertation: an essential guide for business students, Prentice Hall, New York, NY.

Fowler, F 2013, Survey research methods, 5th edn, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Gbadamosi, A, Bathgate, I & Nwankwo, S 2013, Principles of marketing: a value-based approach, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Gooderham, P, Grøogaard, B & Nordhaug, O 2013, International management: theory and practice, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Groh, A, Fearon, P, Jzendoorn, M, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M & Roisman, G 2017, ‘Attachment in the early life course: meta‐analytic evidence for its role in socio-emotional development’, Journal of Theoretical of Social Psychology, vol. 11, no. 1, 70-76.

Guirdham, O & Guirdham, O 2017, Communicating across cultures at work, 4th edn, Palgrave, London.

Hanzlick, M 2015, Management control systems and cross-cultural research: empirical evidence on performance measurement, performance evaluation, and rewards in a cross-cultural comparison, Josef EUL Verlag, Lohmar.

Hartmann, J & Vachon, S 2017, ‘Linking environmental management to environmental performance: the interactive role of industry context’, Business Strategy and Environment, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 359-374.

Hays-Thomas, R 2017, Managing workplace diversity and inclusion: a psychological perspective, Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY.

Heesen, B 2015, Effective strategy execution: improving performance with business intelligence, Springer, Berlin, Germany.

Holbeche, L 2017, Influencing organisational effectiveness: a critical take on the hr contribution, Routledge, New York, NY.

Holz, M 2016, Suggestions for cultural diversity management in companies: derived from international students’ expectations in Germany and the USA, Anchor Academic Publishing, New York, NY.

Hong, J & Lee, Y 2014, The influence of national culture on customers’ cross-buying intentions in Asian banking system: evidence from Korea and Taiwan, Routledge, New York, NY.

James, A 2017, Work-life advantage, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Knight, J 2013, International education hubs: student, talent, knowledge-innovation models, Cengage, New York, NY.

Laroche, L & Yang, C 2014, Danger and opportunity: bridging cultural diversity for competitive advantage, Taylor & Francies Group, London.

Maktoum, M 2017, Reflections on happiness & positivity, Explorer Publishing & Distribution, Dubai.

Marschan-Piekkari, R, Welch, D & Welch, L 2014, Language in international business: the multilingual reality of global business expansion, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Molinsky, A 2013, Global dexterity: how to adapt your behaviour across cultures without losing yourself in the process, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA.

Moran, A 2015, Managing agile: strategy, implementation, organisation and people, McMillan, London.

Mor-Barak, M 2014, Managing diversity: toward a globally inclusive workplace, SAGE Publishing, Los Angeles, CA.

Nestor, P & Schutt, R 2014, Research methods in psychology: investigating human behaviour, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Notarnicola, N 2015, Global inclusion: changing companies strategies to innovate and compete introduction, Franco Angeli, Milan.

O’Reilly, C, Caldwell, D, Chatman, J & Doerr, B 2014, ‘The promise and problems of organisational culture: chief executive officer personality, culture, and firm performance’, Group & Organisation Management, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 595–625.

Otley, D 2016, ‘The contingency theory of management accounting and control: 1980–2014’, Management Accounting Research, vol. 31, no, 1, pp. 45-62.

Ozbilgin, M 2015, Global diversity management, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Pachankis, J, Hatzenbuehler, M, Rendina, J, Safren, S & Parsons, J 2015, ‘LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioural therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: a randomised controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach’, Journal of Consult Clinical Psychology, vol. 83, no. 5, pp. 875–889.

Pantouvakis, A & Bouranta, N 2017, ‘Agility, organisational learning culture and relationship quality in the port sector’, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 366-378.

Parhizgar, K 2013, Multicultural behaviour and global business environments, Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY.

Park, K, Song, H, Yoon, S & Kim, J 2013, ‘Learning organisation and innovative behavior: the mediating effect of work engagement’, European Journal of Training and Development, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 75-94.

Picardi, C & Masick, D 2013, Research methods: designing and conducting research with a real-world focus, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Prescott, J 2016, Handbook of research on race, gender, and the fight for equality, Information Science Reference, Hershey, PA.

Ratten, V, Braga, V & Marques, C 2017, Knowledge, learning and innovation: research insights on cross-sector collaborations, Cengage, New York, NY.

Ren, F & Zhai, J 2014, Communication and popularisation of science and technology in China, Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Rovai, A, Baker, J & Ponton, M 2013, Social science research design and statistics: a practitioner’s guide to research methods and SPSS analysis, Watertree Press, Chesapeake, VA.

Sarea, M & Hanefah, M 2013, ‘The need of accounting standards for Islamic financial institutions’, International Management Review, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 50-58.

Saunders, M & Lewis, P 2017, Doing research in business and management, Pearson Education Limited, London.

Schellwies, L 2015, Multicultural team effectiveness: emotional intelligence as success factor, Anchor Academic Publishing, Hamburg.

Sheldon, J & Daniele, R (eds.) 2017, Social entrepreneurship and tourism: philosophy and practice, Cengage, New York, NY.

Stahl, G, Tung, R, Kostova, T & Zellmer-Bruhn, M 2016, ‘Widening the lens: rethinking distance, diversity, and foreignness in international business research through positive organisational scholarship’, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 47, no. 6, 621–630.

Tan, A & Perleth, C (eds.) 2015, Creativity, culture, and development, Springer, London.

Tate, C 2015, Conscious marketing: how to create an awesome business with a new approach to marketing, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Tracy, J 2013, Qualitative research methods: collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester.

Triana, M 2017, Managing diversity in organisations: a global perspective, Taylor & Francis Group, London.

Wang, C & Rafiq, M 2014, ‘Ambidextrous organisational culture, contextual ambidexterity and new product innovation: a comparative study of UK and Chinese high-tech firms’, British Journal of Management, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 58–76.

Wróblewski, Ł 2017, Culture management: strategy and marketing aspects, Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH, Berlin.

Yanow, D & Schwarts-Shea, P 2014, Interpretation and method: empirical research methods and the interpretive turn, 2nd edn, M.E. Sharpe, London.

Yip, G & McKern, B 2016, China’s next strategic advantage: from imitation to innovation, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Yu, Y, Dong, X, Shen, K, Khalifa, M & Hao, J 2013, ‘Strategies, technologies, and organisational learning for developing organisational innovativeness in emerging economies’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 2507-2514.

Zeiser, A 2015, Transmedia marketing: from film and try to games and digital media, Focal Press, London.

Zolait, A 2013, Technology diffusion and adoption: global complexity, global innovation, Information Science Reference, Hershey.