Introduction

One of the central threats to the clinical well-being of the population continues to be the problem of overweight and obesity and all the disruptive consequences that these conditions lead to. It is well known that obesity causes a multitude of pathological changes in the patient’s body, including any problems related to impaired metabolism (Blüher, 2019). It is essential to recognize that the problem of obesity has no measurable age, gender, or socioeconomic boundaries, which means this dysfunction can affect any individual; however, it is during adolescence that obesity proves to be extremely dangerous. During puberty, when an adolescent’s body naturally balances hormones and adjusts metabolic processes, obesity can cause crippling abnormalities. As an adult, such abnormalities can lead to exacerbations of chronic diseases. In addition, if a teenager suffers from being overweight, it can cause psychological trauma and additional eating disorders, especially caused by school bullying and lack of attraction to peers. Thus, there is a tangible need for a clinical intervention for this patient population that can preventively address the problem of obesity among adolescents. This research paper aims to explore not only the possibilities of such an intervention but also to evaluate the benefits and limitations of the proposed recommendations critically. To be specific, the problem of obesity and overweight is being studied for adolescents from Tarrant County, Texas; however, it is assumed that the recommendations generated are true for all adolescents with this problem.

Background Information: Tarrant County, Texas

The problem of obesity, including among adolescents, has been traditionally — but not entirely deservedly — associated with the U.S. population. These stereotypical judgments as a whole are not entirely made up: according to statistics from the CDC (2021), approximately 42.4% of American adults are obese, and this number has risen significantly over the past twenty years. Among Texas’ adolescent population, a similar prevalence persists. Data reports that as of 2019, approximately one in six students in grades 9-12 in Texas were overweight, with 16.9% of Texas teens diagnosed with obesity (CDC, 2019). These statistics report that obesity and overweight are a highly relevant problem among local youth, which means there is an urgent need to address this problem in a reactive manner.

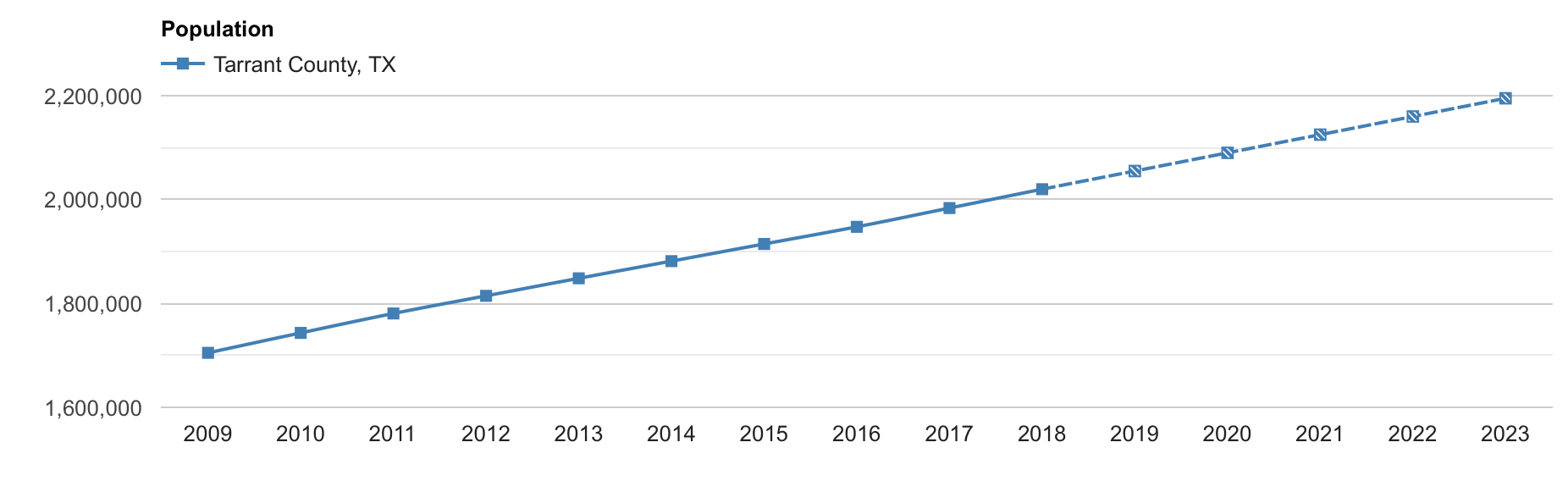

The choice of Tarrant County as one of the largest counties in the state of Texas was not an accident; instead, the motivation for choosing this geographic area is legitimate. By now, Tarrant County has more than 2,100,000 local residents, a number that has increased linearly over the past decade (Figure 1). Of that number, the government reports that 26.0% of the population is under eighteen years of age and, therefore, teenagers (Census, 2021). This is one of the highest numbers not only in all of Texas but in the United States: in Tarrant County, literally, one in four residents is a teenager.

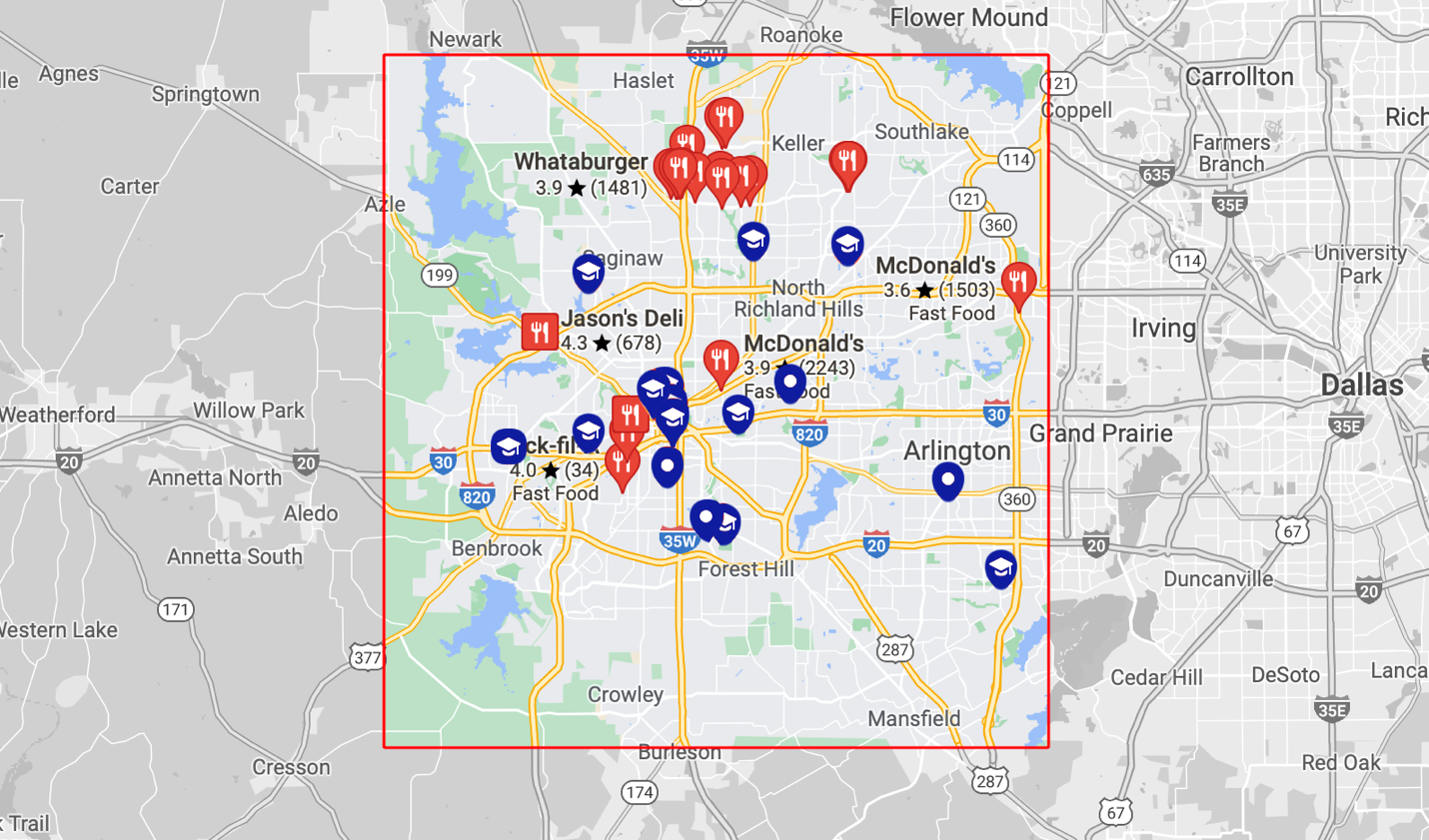

This section critically needs to explain the underlying causes of obesity that cause many adolescents to become overweight and a number of associated health consequences. The NHS (2019) reports that the main pattern that leads to dramatic fat gain is that the individual moves too little and eats too much. As a result of this low activity, excess calories are not spent on exercise, and the body deposits them as a reserve in fat tissue. Scientific studies link the pandemic prevalence of obesity among adolescents to the widespread use of convenience foods. For example, it has been reported that approximately one in three adolescents in the sample consumes fast food at least once a week; as a result, the availability of fast food and abdominal obesity among adolescents found a strong positive correlation (Mohammadbeigi et al. 2018). Extrapolating these reflections to a map of Tarrant County (Figure 2) shows that fast food outlets are often located near local schools and colleges. Taken together, this data shows that for teens from this county, eating at fast-food chains is not uncommon, leading to obesity and overweight problems among Texas youth.

Clinical Intervention

Clinical intervention for preventive management of obesity is a priority need for communities. This need is driven by a general desire to improve the health of the nation and relieve the burden on the health care system, as being overweight and even more so being obese are reliable predictors of the development of chronic problems in an individual. Studies show that obesity is positively associated with risks of diabetes, hypertension, kidney failure, heart attacks and strokes, dementia, and even some cancers (Blüher, 2019). Furthermore, obesity in adolescents is an additional complicating factor for the more severe course of COVID-19 (Rivera, 2021). Consequently, the disruptive effects of obesity result in shorter life expectancy and decreased overall comfort and safety. However, as reported by Blüher (2019), any interventions used so far have not had long-term benefits because they have failed to address reliably managing obesity problems among adolescent patients. As a consequence, a need is created to develop new preventive prevention systems to address this problem.

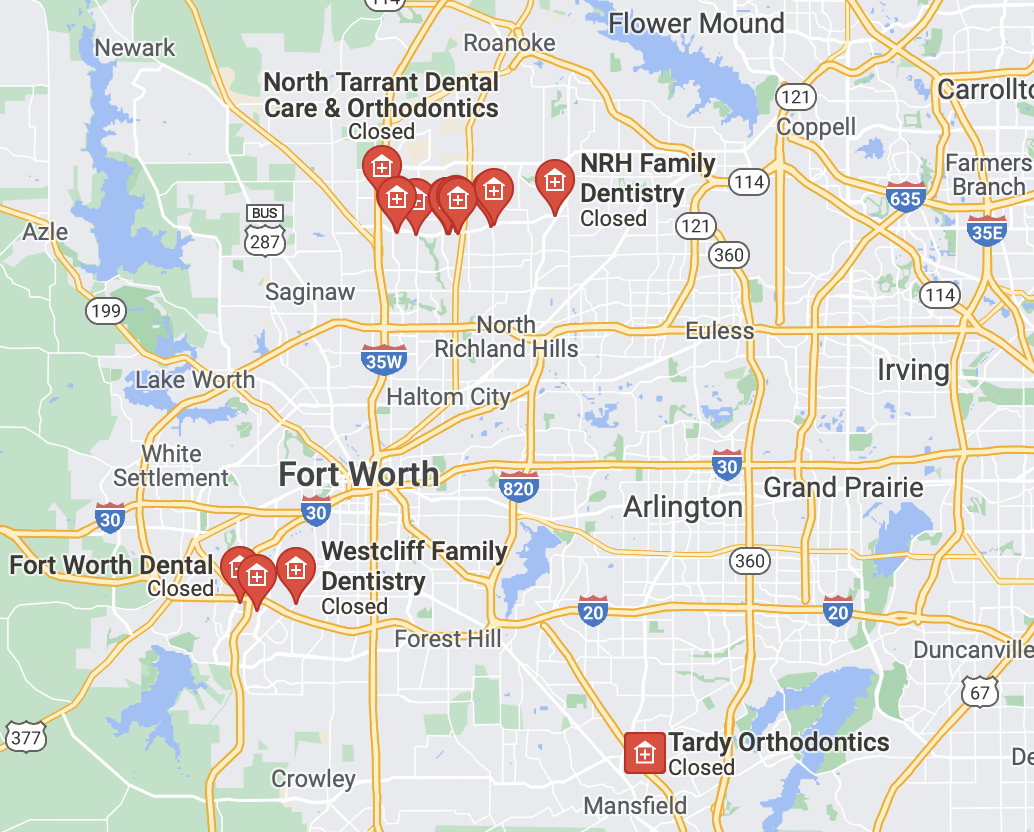

As part of the solution being developed, the recommendation for clinical intervention is preventive control of the obesity problem through educational programs distributed, including in adolescent dental clinics and hospital dental departments. Dentistry as a medical field, motivated for the purposes of the solution being developed, makes it possible to identify problems related to obesity at an early stage. In fact, oral health acts here as a mediator between malnutrition — a key predictor of overweight problems — and obesity, leading to destructive consequences in the long term. This transparent link, combined with the comparatively easy detection of oral health problems by professional dentists, creates great potential for preventive management of obesity issues and the prevention of the spread of this diagnosis through a sound educational program. As before, Tarrant County was again not randomly chosen for the purposes of this paper because, as shown in Figure 3, there are quite a few dental offices in the county. This increases the outreach to teens and helps to implement recommendations to curb overweight not locally but throughout Tarrant County.

Many studies in recent years have developed the theme of the relationship between obesity and clinical problems related to the oral cavity. In fact, this correlation should be viewed from two angles. First, systematic poor diet, unbalanced diet, consumption of added sugar, and fast food naturally leads to oral disease; based on this, the dentist can predict the formation of an overweight patient. Second, if the patient is already overweight but has not yet entered the stage of obesity, a positive opportunity for change is created. However, even being overweight has an impact on oral health. For example, studies show that being overweight doubles the likelihood of developing periodontitis, an inflammatory disease of the soft tissues of the gums (Martinez-Herrera et al., 2017). Consequently, both of these perspectives — improper diet and already being overweight — should be considered in the current development.

How Diet Influences Oral Health

The need for a proper diet and balanced nutrition stems from the desire to maintain good oral health. The mouth is the first barrier to the mechanical transformation of food, and saliva enzymes are present to break down large polymeric molecules partially and disinfect passing food fragments. Oral health is affected by a number of factors of the food used, including its hardness, salinity, pH, and the amount of sugar used. Lack of solid foods in the diet leads to dysfunction of the chewing muscles of the jaw, resulting in a reduced dental performance of the patient. Using only plant-based foods (vegetarianism and veganism) has been shown to lead to impaired salivary acidity, cavity formation, and the salivary deficiency (GSD, 2019). Meanwhile, tooth decay is one of the most common problems among adolescent patients, which seems to be related to an excessive acidic diet. By consuming large amounts of carbohydrates, among which added sugar, dental hard tissues become demineralized, resulting in a dramatic decrease in dental tissue pH (ADA, 2021). In turn, the decrease in acidity among the oral cavity catalyzes the development of pathogenic microorganisms that populate the damaged tooth tissue and use nutrients to reproduce (Figure 4). The WHO (2018) reports that approximately 0.5 to 3.5 teeth in twelve-year-olds are subject to carious damage. Meanwhile, “dental caries is costly to health care and negatively affects well-being” (Moynihan, 2016, p. 149). Thus, innocuously starting dental caries can lead to the development of pulpitis, tooth nerve damage, and premature tooth death.

Although carious tooth tissue damage is one of the most common causes of oral disease, it would be a mistake to associate the destructive effects of food only with tooth decay. For example, a patient’s teeth and gums may be susceptible to erosive lesions that result in thinning of dental tissue. Erosive processes differ from caries because, in this case, the dental tissue is only destroyed (as shown in Figure 4), but there is no bacterial contamination of the cavities that have formed. The formation of erosive foci is traditionally associated with an excessively acidic diet: this includes most carbonated lemonades with added sugar. Thus, an improper diet with an excess of chemically unbalanced foods and added sugar leads to several degenerative processes.

Link to Obesity

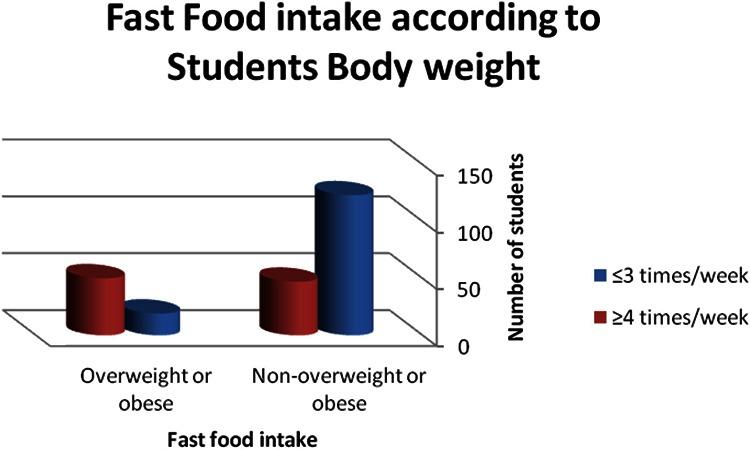

As a consequence, an ill-balanced diet in adolescents affects not only oral health but also overweight problems. Statistics show that only 1 in 10 overweight teens does not consume fast food, while the preponderance of overweight or obese students consume fast food at least three times a week, as shown in Figure 5. However, the oral cavity is a convenient area for clinical observation because it is possible to predict obesity from the presence of caries and erosions if the child’s diet is also examined. This means that during a dental examination, the dentist will always be able to make a preliminary assessment of the type of food that the patient systematically eats and then suggest dietary adjustments based on the fear of obesity. This is the assumption that is the idea behind the clinical intervention being developed.

The possibility of using dental offices as the primary gateway to detect the likelihood of overweight in a Texas adolescent turns out to be highly convenient for current clinical intervention purposes. Common recommendations suggest that adolescents should see a dentist at least twice a year (once every six months), which creates a positive dynamic for monitoring changes in oral health (ADG, 2019). The more “red flags” a doctor sees in a patient’s mouth, the more likely it is that teens have a poor diet, which has the potential to affect overweight problems. In this case, the physician has the opportunity to alert the child to the real risks and provide education on proper dietary intake. A competent doctor should clearly understand the psychology of eating disorders and be knowledgeable about aspects of addiction to specific foods. It is unacceptable to ban an adolescent from consuming carbonated lemonades or fast food to fix their diet because, as previously stated, such tactics have been shown to be ineffective in the long run; even if a child gives up these foods for several weeks, they will eventually return to them (Blücher, 2019). Instead, the clinician should suggest alternatives for the specific foods that are most addictive and transform the Texas teenager’s diet in a planned but effective manner. This may involve gradually removing one unhealthy food per week from the diet so that it is replaced with a healthy and tasty alternative that the patient will enjoy. Ultimately, any consolidation of change and positive results can only be achieved when the adolescent is self-aware and fully aware of the problem and is willing to see the consequences.

Measuring Outcomes

Because oral diseases that lead to overweight problems are most often treated clinically but almost never left to develop further when supervised by a physician, any carious and erosive dental changes are difficult to observe over time. More specifically, an adolescent patient who comes to the doctor for an examination with complaints of caries is the most likely to receive therapeutic treatment for this caries, which means that further evolution of this problem proves difficult. However, in general, the positive trend remains that in the case of a child’s improper diet — and in the absence of the same problems in the family history — degenerative lesions of the oral cavity are more frequent. Consequently, if the number of disease development foci has increased after six months, the child has never been able to transition to a healthy diet, and thus their risk of becoming overweight naturally increases. However, this method is not highly accurate or reliable, as several limitations affect the validity of the measurements at once. First, the presence of hereditary dental problems can be ignored. Second, during initial examinations, the doctor may not have noticed hidden forming cavities that have evolved six months later. Third, the development of tooth and gum degenerative lesions is ambiguous evidence of a teenager’s illiterate diet, although there is a connection.

However, if the adolescent is indeed following a new diet and following the lessons learned from the doctor, it may be noticeable during a dental exam. In particular, avoiding junk food and proper oral hygiene leads to less plaque. In addition to a reduction in the number of carious lesions, the intensity of gingivitis is also reduced, as the case studies suggest (Sosiawan et al., 2020). Notably, the level of artificial sugar consumed can be assessed by rapid patient blood tests. Although it may seem an uncommon practice, giving blood for a complete test before a therapeutic intervention has its advantages. First, by doing so, the physician assesses the amount of glucose in the blood, which, in addition to evidence of the consumption of sugary foods, can be a predictor of the development of diabetes. Second, with this screening, the therapist can detect blood inflammation and pathological infections, which has implications for choosing therapy for diseased teeth (Cotter & Dilliard, 2019). Including hidden dental abscesses that are not symptomatic can be detected through laboratory blood testing. Thus, clinical examination of a patient’s blood in a dental clinic setting makes just as much sense.

Meanwhile, a physician interested in treatment may suggest that the patient keep a personal dietary observation diary in order to keep track of progress. Writing down absolutely all the foods consumed in a calendar can be fraught with the development of eating disorders, so an alternative is suggested: for a limited time (for example, one month), the child records all the unhealthy foods he or she has consumed and indicates their amounts. An example of a fragment of such a diary is shown in Table 1 below: this format may be sufficient to trace the teenager’s diet and draw conclusions about the balance of the diet. Even in this case, however, it should be understood that there are limitations. For example, there is a research pattern that subjects under observation tend to change their behavior for a more encouraged one, which distorts the actual results (Purssell et al., 2020). In addition, it is possible that an adolescent may forget to write down foods or lie about precisely what he or she consumed. On the other hand, keeping a diary fosters systematicity and responsibility for one’s diet, which can be beneficial in combating obesity. The patient shows this diary to the dentist at each visit. However, if the frequency of visits to the dentist is low, the dentist can telecommunicate with the teen via email or messengers to monitor the dynamics.

Conclusion

To summarize, overweight and obesity are a severe threat to the national health care system. Being overweight in adolescents proves to be a particularly sensitive problem, as it is not only associated with the most critical changes in the patient’s metabolism but also entails dangerous mental trauma for the emerging personality. Being overweight and obese has been shown to be positively associated with the development of chronic disease, diabetes, kidney and heart disease, and cancer. Consequently, the national medical agenda is interested in preventively addressing obesity among adolescents. This research paper developed the idea of using dental offices as the primary gateway to detect potential obesity among Texas adolescents. The choice of a particular area, Tarrant County, was driven not only by its demographics but also by the infrastructural characteristics of the region, which may cause many local high schools and college students to consume fast food systematically. This affects oral health and leads to overweight problems. The clinical intervention involves the use of treating dentists to screen oral health. Dynamics are measured through regular monitoring of dental and gum health and/or through the use of a food diary to assess the adolescent patient’s diet. In other words, dentists have an almost unique opportunity to detect the potential development of obesity in a patient through systematic, high-quality, and detailed oral health surveillance.

This intervention is expected to bring about positive changes in the overweight crisis among Texas youth not only in the short term but also in the long term. However, it should be kept in mind that there is no perfect solution to this problem, and therefore each of the recommendations is associated with some risks. For example, oral diseases are ambiguously linked only to an incorrect diet. In addition, it is likely that the patient will refuse to keep a food diary or will not want to write down all the foods. All this together distorts the results of therapy and has a negative impact on clinical intervention. This is why the procedure of educating the adolescent and absolutely acknowledging the need for change should be paramount. Once a teenager is fully aware of his or her oral problems and understands that the cause of these problems — or one of the causes — is an improperly formed diet, and is aware of the consequences of continuing such a diet, it is expected that this will lead to a desire to change his or her eating habits.

References

ADA. (2021). Nutrition and oral health. Department of Scientific Information, Evidence Synthesis & Translation Research, ADA Science & Research Institute, LLC. Web.

ADG. (2019). How to know when your teenager should go to the dentist. Aurora Dental Group. Web.

Almuhanna, M. A., Alsaif, M., Alsaadi, M., & Almajwal, A. (2014). Fast food intake and prevalence of obesity in school children in Riyadh City. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 14(1), 71-80.

Blüher, M. (2019). Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 15(5), 288-298. Web.

CDC. (2019). Obesity / weight status. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System CDC. Web.

CDC. (2021). Adult obesity facts. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Web.

Census. (2021). QuickFacts. Census. Web.

Cotter, J. C., & Dilliard, J. A. (2019). What do lab values mean? DDH. Web.

GSD. (2019). Is a vegan diet bad for your teeth? Golden State Dentistry. Web.

Martinez-Herrera, M., Silvestre-Rangil, J., & Silvestre, F. J. (2017). Association between obesity and periodontal disease. A systematic review of epidemiological studies and controlled clinical trials. Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal, 22(6), 708-715. Web.

Mohammadbeigi, A., Asgarian, A., Moshir, E., Heidari, H., Afrashteh, S., Khazaei, S., & Ansari, H. (2018). Fast food consumption and overweight/obesity prevalence in students and its association with general and abdominal obesity. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 59(3), 236-240. Web.

Moynihan, P. (2016). Sugars and dental caries: evidence for setting a recommended threshold for intake. Advances in Nutrition, 7(1), 149-156. Web.

NHS. (2019). Causes. NHS. Web.

ODN. (2018). Tarrant County, TX. Open Data Network. Web.

Purssell, E., Drey, N., Chudleigh, J., Creedon, S., & Gould, D. J. (2020). The Hawthorne effect on adherence to hand hygiene in patient care. Journal of Hospital Infection, 106(2), 311-317. Web.

Rivera, E. (2021). North Texas hospitals are seeing more children with COVID. experts say it might get worse. KERA News. Web.

Salat, A. (2020). Initial caries: Management for minimal intervention. Style Italiano. Web.

Sosiawan, A., Krissanti, T. D., Palupi, R., Berniyanti, T., Wening, G. R. S., & Lestari, P. (2020). The relationship of nutritional status and gingivitis in elementary school children. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 11(3), 2471-2475.

WHO. (2018). Diet and oral health [PDF document]. Web.