Organizational Justice

Building relationships in an organizational environment is always fraught with difficulties due to the incongruences in the value systems of the participants. However, universal organizational values are expected to assist in creating a fair workplace for all participants, thus encouraging their motivation and engagement rates to grow. In turn, the development of turnover intention in employees needs to be seen as the key threat to the performance of an organization and its competitiveness. For this reason, exploring how organizational justice in its known forms can affect the turnover intention in staff members is needed.

Definition and Theory Development

Fair treatment of staff members and the promotion of justice at the organizational level are crucial prerequisites to effective management of organizational goals and the enhancement of a company’s progress. However, the lack of a proper understanding of organizational justice often becomes a barrier to creating equity and equality in the corporate environment. Therefore, the phenomenon of organizational justice needs further scrutiny and a more accurate definition.

According to Yean and Yusof (2015), organizational justice is “the fairness associated with the decision related to the distribution of resources within the organization” (Yean & Yusof, 2015, p. 798). Ultimately, the concept of organizational justice is reserved for the allocation of corporate resources and their distribution among staff members. Other scholars opine that organizational justice is a subjective feeling of how employees perceive the fairness in the workplace based on their psychological level (James, 1993; Greenberg& Scott, 1996; Rubino et al., 2018). Hosmer and Kiewitz (2005) write that first and foremost, organizational justice is a behavior science concept that refers to the subjective perception of fairness. In other words, organizational justice is not based upon objective morality or recognized justice principles. Instead, it operates on individuals’ personal views on justice and how corporate situations need to be handled in a just and fair manner.

It appears that, in the context of the modern workplace, the idea of corporate justice needs to be stretched to include relationships between staff members and managers. Thus, the extent to which the needs of employees are met with the help of organizational justice can be evaluated. Additionally, since contemporary scholars such as James (1993), Greenberg and Scott (1996), and Rubino et al. (2018) point out the subjectivity of organizational justice, it only makes sense to examine the issue through first-hand experiences of employees.

Structure and Dimensions

Notably, the concept of organizational justice is usually split into several categories that allow differentiating between the circumstances in which the said justice is served. Specifically, justice in distributing corporate resources, ensuring compliance with workplace standards, and managing conflicts is typically separated into the appropriate categories. It is believed that the specified paradigm allows meeting the principles of organizational justice closer, which, in turn, increases the levels of employee retention within a company (Sokhanvar, Hasanpoor, Hajihashemi, & Kakemam, 2016). Namely, by ensuring justice on the described levels, a manager can foster loyalty and commitment in staff members, which, in turn, serve as the tools for keeping staff members within an organization.

Distributive Justice

The concept of distributive justice is quite self-explanatory since it suggests that organizational resources should be arranged in the way that leaves all parties satisfied (Akram, Lei, Haider, Hussain, & Puig, 2017). However, attaining the goal of redistributing organizational resources is likely to entail significant challenges for company members due to the issues that a shift in financial strategy and structure of an organization causes.

One of the classic theories addressing the issue of distributive justice is Adams’ (1963) equity theory. Developed by a workplace and behavioral psychologist, equity theory seeks to determine whether the distribution of resources is fair for all relational parties (Adams, 1963). The crux of Adams’ theory hinged on the assumption that individuals compare their input and work outcomes and those of others (Adams, 1963). If they notice injustice, they strive to restore balance, which does not always happen in constructive ways. Simply put, employees feel neglected and demotivated if they realize that the output does not match the input (Adams, 1963). Both input and output can be rationalized in various ways. Employees contribute with their effort, skills, loyalty, and enthusiasm, and they expect remuneration, praise, recognition, reputation, and other forms of reward in return.

Procedural Justice

Another critical aspect of a company’s functioning in the global market, the receives very little support as one of the critical components of the performance management process, the distributive justice implies that the management of corporate resources needs to be shaped on the idea of using the existing frameworks for measurement to identifying the required size and shape. The concept of procedural justice was introduced by Folger and Greenberg (1985) as an alternative and addition to the predominant distributive justice framework in the field of workplace psychology. Folger and Greenberg (1985) challenged the superiority of outcome: the scholars argued that in reality, workers were concerned not only with the ultimate decision but also with how it was made. For instance, in the case of a promotion or a pay rise, employees would often want to know who decided on that and on what grounds. In summation, the domain of procedural justice overviews questions of allocation process as opposed to allocation outcomes.

The perception of procedural justice comes down not only to the individual and his or her unique characteristics but also to their cultural background that might play the decisive role in their views on organizational justice. In their work, Tata, Fu, and Wu (2003) compared and contrasted Chinese and American (US) employees’ perception of procedural justice across various subscales and dimensions. The dimensions of national culture included uncertainty avoidance, societal emphasis on collectivism, and gender egalitarianism) whereas the three principles of procedural justice entailed consistency, social sensitivity, and account-giving. Tata et al. (2003) discovered that the cultural factor impacted what people considered to be fair and just. Among the most interesting findings is the fact that Chinese respondents found social sensitivity as fair while individualistic Americans did not share the same sentiment.

Such findings raise a logical question as to whether Western notions of organizational justice (and as this section demonstrates the overwhelming majority of organizational justice scholars are from the West) hold true for China. Sun et al. (2017) tested Tyler’s process-based model of policing that suggests that police legitimacy is grounded in distributive and procedural justice as well as police effectiveness. It is suggested that police legitimacy positively influences police cooperation, which is a prerequisite of a well-functioning society or an organization, on a smaller scale. The findings of the study revealed that the process-based policing had a significant support base in China. In particular, procedural justice was the strongest predictor of police legitimacy.

However, interestingly enough, when surveying Chinese employees, Pillai, Williams, and Tan (2001) have found that they were preferring distributive justice to procedural, which differentiates China from other countries analyzed for the study. All the countries demonstrated a strong relationship between trust and the perception of organizational justice (PIllai et al., 2001). However, Chinese employees were more in favor of distributive justice which was explained by their preference for short-term benefits as opposed to procedural justice that often yields long-term benefits.

Interactional Justice

Finally, the interactional justice needs to be brought up as one of the pillars of managing intersectional crimes and the issues emerging in tending to the needs of vulnerable groups. Interactional justice suggests implementing social justice on an interpersonal level. Akin to procedural and distributive justice, interactional justice impacts employees’ perceptions of systemic justice. If distributive justice deals with the result and procedural – with the process, interactional justice deals with the manner of how justice is served in an organization (Greenberg, 1993). In other words, interactional justice focuses on the kind of treatment that employees receive while organization procedures are reinforced and maintained (Bies & Moag, 1986; Greenberg, 1993). Scholars that put forward the concept of interactional justice opine that the “style” in which employees are treated should be respectful and dignified.

Beugre (1996), Cropanzano et al. (2002), and Greenberg (1997) report that failure to execute justice results in theft, workplace aggression, and retaliation. These antisocial behaviors are often triggered by the insensitive, disrespectful treatment at the hand of top managers and employers. A study by Mikula, Petrik, and Tanzer (1990) showed that oftentimes, individuals are even more attentive to interactional as opposed to distributive and procedural justice. The survey revealed that participants’ accounts of injustice often referred to the manner in which they were treated in interpersonal interactions. Mikula et al. (1990) report participants’ disappointment with impolite, insensitive, and inconsiderate treatment as well as the demonstration of a lack of loyalty and integrity. To sum up, interactional justice is as important as the other two dimensions; it influences how people perceive organizational justice on the whole.

Relationships between various dimensions

It is also worth noting that there are several dimensions through which the issue at hand can be viewed. Specifically, it can be examined through the lens of the two- and three-dimensional viewpoints.

Two-dimensional view

The two-dimensional conceptualization of organizational justice may lack additional insight, yet it helps to focus on specific issues without introducing various distractions. Namely, the combination of distributive and procedural justice types has helped to ensure compliance with the existing standards and promote equality across a company (Akram et al., 2017).

Three-dimensional view

Given the flawless implementation of the two-dimensional model, one might think that the introduction of the third dimension into the analysis may have obscured the process of implementing organizational justice properly. However, with the advent of a new model of communication, where intersectionality and diversity become the center of attention, the need for the third dimension has emerged. Namely, the focus on interactions, specifically, communication in a diverse environment and the management of interpersonal dialogue has shaped the discourse surrounding the organizational justice notion (Akram et al., 2017). Thus, the inclusion of the three-dimensional view has been necessitated by the change toward the focus on communication and experience sharing in the context of the modern business environment.

Turnover Intention

Although workforce used to be seen as one of the most disposable elements of a company’s assets, nowadays, it is typically seen as by far the most valuable resource that a company can have. Therefore, the attitudes toward building relationships with staff members have changed drastically as the focus quickly shifted toward building long-lasting connections with employees. Thus, it has become important to ensure that staff members do not contemplate leaving the organization, hence the significance of evaluating their turnover intention.

Definition

As its name suggests, turnover intention is the “final cognitive decision making process before an employee decides to leave a job” (Lim, Loo and Lee, 2017, p. 28). There should be a distinction between turnover and turnover intention. Liu, Liu, and Hu (2010) point out that turnover intention signifies an individual’s behavioral attitude to withdraw from an organization while turnover is the act of separation itself. Wong, Ngo, and Wong (2002) define turnover intention as a combination of both thinking and planning one’s leave from an organization. The turnover intention might or might not result in an actual decision to quit.

The proposed definition is slightly narrower than the broad idea of contemplating leaving the job, in general. As a result of the identified specification, one can measure the threat of change in employee turnover rates more accurately. However, other approaches toward defining the concept of turnover intention have been suggested. Despite the fact that all of the definitions provided above tend to purport the same idea, they are still very helpful for the research since they provide insights into the factors that cause employee turnover rates to change. Nevertheless, to determine the actual factors that incline staff members to leave their organizations, several specific models have been built. These models allow drawing connections between the key factors that affect the changes in organizational justice and employee turnover.

Price’s Theoretical Model of Voluntary Turnover

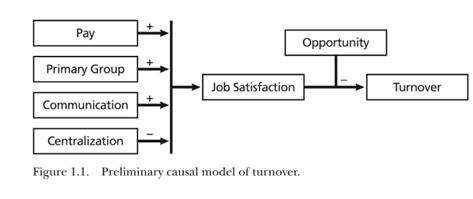

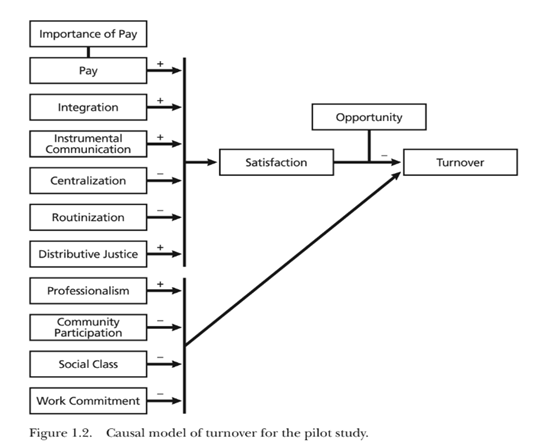

The Casual Model of Voluntary Turnover (CMVT) suggested by James L. Price offers a unique way of looking at the factors that drive employees’ decisions to quit their jobs (see Image 1,2). The specified model has been credited as one of the three major theoretical frameworks for explaining the turnover phenomenon (Cho, Lee, & Kim, 2019). The other two are the frameworks by Mowday and Mobley (Cho et al., 2019). However, Price’s model seems to be by far the most comprehensive and well-rounded of all three. The framework introduces key determinants of employees’ decision to leave, thus defining the probability of a turnover (Cho et al., 2019).

According to Price, the change in turnover rates is defined by four core factors. Namely, payment, communication, centralization, and job satisfaction influence the levels of turnover in a workplace (Cho et al., 2019). According to the model, the first three factors determine the extent of job satisfaction, which, when reaching a specific limit, affects an employee’s decision to leave (Cho et al., 2019). Thus, Price’s model offers a slightly simplistic but generally correct interpretation of turnover as a phenomenon.

However, even Price’s model could not possibly take every factor affecting the changes in turnover rates into account. Moreover, with the emergence of innovations, especially those in the communication field, new factors affecting turnover rates develop. Therefore, it is worth considering the factors influencing the levels of turnover in modern companies separately. Thus, one will have a better insight into how employee retention rates can increase.

Influencing Factors

As emphasized above, the lack of financial motivation and especially incongruences between the amount or quality of work performed and the reward received for it are the main factors defining employee turnover. Studies show that low compensation is not necessarily a factor for young professionals that are only starting to build their career, yet it is crucial for the employees that have already gained experience in their field (Lim et al., 2017). Therefore, organizations need to consider introducing appropriate compensation to staff members to ensure that they do not leave for jobs that pay higher. The compensation issue involves not only salaries set at a proper level but also other benefits, such as paid sick leave, maternity leave, medical benefits, and other types of financial support.

The issue of insurance plays a particularly important role in determining the extent of employee turnover. Studies show that staff members are less likely to leave the workplace environments with better health insurance options (Kerse & Babadağ, 2018). Therefore, it is essential to ensure that employees receive high-quality options for addressing their health issues. Overall, the compensation factor is by far one of the most important ones in an employee’s decision to resign.

The level of workload and, therefore, the specifics of work-life balance is another important contributor to employees’ willingness to quit their current job. The specified issue is of particular importance to jobs that imply higher levels of stress and psychological, as well as physical, exhaustion. For instance, in nurses, the threat of a workplace burnout has been extraordinarily high for the past few years (Haghighinezhad, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, Ashktorab, Mohtashami, & Barkhordari-Sharifabad, 2019). With the current pandemic of coronavirus, the levels of workplace burnout have increased exponentially, causing the workplace conditions to become unbearable for a number of nurses (Haghighinezhad et al., 2019). As a result, many staff members choose to resign, increasing employee turnover rates in their respective places of work (Haghighinezhad et al., 2019). The scenario described above proves that the factors affecting turnover rats are not necessarily under the control of managers and workplace leaders all the time. Specifically, in the case with coronavirus, the low staffing rates along with the rapid rise in the number of patients made the workload and the subsequent burnout to skyrocket, hence the increase in employee turnover (Lim et al., 2017). Similarly, the problem of overscheduling, to which a rise in employee turnover is often attributed, is not necessarily under the control of managers (Haghighinezhad et al., 2019).

However, a significant number of factors that lead to higher employee turnover rates and the development of turnover intentions within staff members can, in fact, be controlled by their organizations. For example, the lack of organizational justice is one of the key contributors to turnover rates increase (Kerse & Babadağ, 2018). Specifically, studies show that the development of nepotism in an organization is likely to lead to an increase in turnover intention rates (Haghighinezhad et al., 2019). According to the definition provided by Kerse and Babadağ (2018), nepotism is “actual or perceived preferences granted to a family member by another family member” (p. 632).

However, even when family members are not involved, preferences for some staff members in the workplace environment will discourage others and create an unhealthy environment, causing an increase in turnover intentions. Known as favoritism, the “act of offering jobs, contracts and resources to members of one’s own social group in preference to others who are outside the group” is an admittedly unfair strategy that will rightfully result in an increased turnover rate when applied in organizational setting (Bramoullé & Goyal, 2016, p. 17).

The reasonable question arises as to whether organizational justice could help with mitigating the effects of job burnout or eliminate the trend altogether. Jin et al. (2015) inquired about the relationship, motivated by not only the lack but also ongoing loss of excellent medical cadres in Mainland China. The scholars admit that job burnout is a complex phenomenon whose origin and occurrence cannot be attributed strictly to one cause. In Mainland China, the possible contributing factors are a relatively low remuneration, unhealthy relationships between patients and doctors, external pressure and poor management. Jin et al. (2015) opine that it is reasonable to concentrate on and pay special attention to organizational justice because it is one of the few factors that hospitals can gain control over. After surveying 135 medical interns, Jin et al. (2015) concluded that organizational justice was negatively correlated with job burnout. In other words, the more fair medical interns perceived the organization they were working in, the less likely they were to be pushed to the verge of burnout.

Another field of occupation that Chinese researchers have been taking interest recently is correctional organizations. Lambert et al. (2018) explain that positive work attitudes, which is moderated by the lack of job burnout, result in employees’ better compliance with rules, proactive behavior, and increased support for rehabilitation of offenders. Lambert et al. (2018) surveyed the employees of 352 correctional facilities in Mainland China and found that organizational justice had a favorable effect on their work attitudes. However, interestingly enough, distributive justice had a more pronounced negative correlation with job burnout that procedural. This peculiarity makes Mainland China different from the United States where the concepts of justice originally stem from.

Organizational Justice and Turnover Intention

It is believed that the willingness of staff members to quit their current job is linked not only to the lack of organizational justice, as a whole, but also due to the absence of certain aspects thereof from the workplace environment. Therefore, different forms of organizational justice will have to be considered.

Distributive Justice and Turnover Intention

The distribution of organizational resources needs to be performed in the way that allows a company to benefit in the target setting. At the same time, it is crucial to distribute the said resources in accordance with the principles of equality and equity. Otherwise, the basic principles of organizational justice will be disrupted, which will make staff members feel economically insecure and, possibly, undervalued in the company (Lim et al., 2017). Therefore, the turnover intention is likely to grow with the drop in the distributive justice within the corporate setting. Nevertheless, exploring the correlation between the two factors mentioned above in greater detail is necessary. Thus, one will be able to grasp the nuances of the correlation between different types of organizational justice and the levels of employee turnover intention.

Procedural Justice and Turnover Intention

The concept of procedural justice is fairly simple as it revolves around the reward that employees receive for their performance. The specified definition has been provided by Tourani et al. (2016) implies that employees;’ enthusiasm and, therefore, their turnover intention rates hinge on the extent to which procedural justice is followed in the workplace.

Disproportional rewards for job performance not only reduce the levels of employees’ motivation but also introduce confusion into their understanding of organizational values, studies warn. In the context of the Chinese organizational environment, the lack of procedural justice often sends staff members mixed signals about the behaviors that are deemed as positive and negative respectively, research warns (Jiang, Gollan, & Brooks, 2017). As a result, staff members tend to resign and seek other workplace environments, which suggests that the absence of procedural justice leads to a higher turnover intention.

Interactional Justice and Turnover Intention

The factors of nepotism and favoritism gain especial weight in discussing the issues of interactional justice and turnover intention. Kerse and Babadağ (2018) argue that the introduction of nepotism into the workplace setting affects staff members’ motivation extensively. Specifically, nepotism in a company leads to employees losing their enthusiasm and loyalty for the company, as the example of the Chinese business environment shows (Jiang et al., 2017). Specifically, nepotism has been deeply engrained into the Chinese business culture due to the centuries of viewing it as an essential part of the Chinese legacy (Jiang et al., 2017). Consequently, even with the recent attempts at addressing the problem of nepotism in the workplace, it still persists in the Chinese business culture (Jiang et al., 2017).

As a result, staff members decide to leave since they see no prospects for professional growth in a nepotism-driven environment (Tourani et al., 2016). Therefore, the development of nepotism and favoritism in the corporate setting reduces the levels of interactional justice and affects turnover rates drastically. The negative impact that a company suffers as a result of nepotism and favoritism is huge since it is drained of its main assets. Likewise, interactional justice is reduced significantly with the introduction of favoritism into the corporate environment. Having a similar effect on staff members, favoritism indicates that interactional justice is no longer the priority for a company. The resulting drop in retention rates and an increase in turnover rates shows that interactional justice has a direct effect on these metrics.

Therefore, organizational justice – or, as the review provided above has shown, the lack of it – has a direct influence on the levels of turnover intentions within a company. Although the phenomenon of organizational justice exists at several levels, even minor issues with at least one of its aspects inhibit employees’ enthusiasm and engagement. As the levels of organizational justice diminish, employees’ engagement and enthusiasm fades away, whereas their dissatisfaction grows. As the levels of dissatisfaction reach the boiling point, staff members start to consider resignation, which leads to higher turnover intentions and, thus poorer performance.

Job Burnout: as the Mediator / The role (impact) of Job Burnout

As emphasized above, workplace burnout as the effect of a drastic increase in workload and the creation of impossible workplace conditions also leads to a rise in turnover rates.

Definition and Measurement

The phenomenon of a job burnout, also known as the workplace burnout, is quite self-explanatory. Implying the development of fatigue and the loss of enthusiasm toward professional responsibilities, job burnout is quite frequent in the settings of high workload and emotional strain. McFadden and Altamirano (2020) define workplace burnout as a “syndrome conceptualized as a result of chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” (p. 45). Remarkably, the authors specify that high workload typically becomes the main factor in the increase in workplace burnout rates in staff members.

Overall, workplace burnout has an immediate effect on employees’ perception of their job. Since the rise in the workload does not allow maintaining the same degree of care and attention to detail, staff members tend to replace swell thought-out actions with mechanical performance, causing the rise in workplace errors (McFadden & Altamirano, 2020). Moreover, the specified changes in the attitude toward workplace responsibilities reduces the latter’s value in the eyes of staff members. As a result, employees lose their motivation, starting to consider resigning (McFadden & Altamirano, 2020). Consequently, turnover intentions rise with the increase in job burnout rates.

The relationship between job burnout and turnover intention is discussed in recent empirical works by Chinese scholars. For instance, Zhang and Feng (2011) conducted a cross-sectional study among 1451 physicians in state hospitals in Hubei, China. The scholars confirmed their hypothesis: the study’s findings revealed that turnover intention was positively related to each subscale of job burnout used for research. Zhang and Feng (2011) concluded that job burnout had a mediatory effect on physicians’ turnover intention, especially particular subscales of burnout syndrome such as emotional exhaustion.

In a more recent study, Liu et al. (2018) addressed the same problem experienced by the Chinese medical workforce. Liu et al. (2018) surveyed a total of 1770 nurses from nine public tertiary hospitals in four provinces located in Beijing, Heilongjiang, Anhui, and Shaanxi. The researchers discovered that burnout was positively correlated with turnover intention: in other words, those nurses who were suffering from burnout syndrome were more likely to contemplate quitting their jobs. At that, as noted by Liu et al. (2018), organizational support played a mediating role between burnout and turnover rate. The study’s implications hinted at the importance of a reasonable incentive system for turnover prevention.

The extent of workplace burnout can be measured by using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). The specified test allows singling out the factors that are likely to cause a rise in the levels of workplace burnout and, thus, inform the further actions to be taken to address the problem of the burnout. Thus, not only the factors such as emotional exhaustion and the rise in workload but also the ones such as depersonalization items can be isolated and influenced in order to reduce the levels of stress experienced by employees.

Thus, as the mediator, workplace burnout links the factor affecting employees’ physical and mental well-being to their intention to leave. As a result, the turnover intent increases once managers fail to regulate the extent of the workload and create the environment in which burnout thrives. The following failure to acknowledge and address the problem, such as the attempt at changing the schedule and expanding the number of employees, will immediately lead to a rise in turnout intent and its levels, leaving an organization without its most valuable resource.

Outcome Variables

The main outcome variables associate with job burnout rates as the mediator for the turnover intention include the extent of the workload, the levels of staffing within a company, and the strategy that the organization uses to manage its workforce. By extension, the factors such as the corporate philosophy on which its HRM strategy is based also affect the situation since they inform managers’ decisions. However, in the grand scheme of events, what defines the outcome for the most part is the company’s ability to recognize its staff as its most valuable resource. The application of an effective talent management strategy and the assessment of the factors reducing employee satisfaction are the crucial strategies for reducing turnover intent in staff members.

Influencing Factors

Presently, the main influencing factors contributing to the rise in the job burnout rates along with the drop in organizational justice and the increase in the turnover intention include uneven distribution of workload, unequal pay, and overall low levels of workplace compensation.

Power Distance: as the Moderator/ The Role (Impact) of Power Distance

Power distance has a direct effect on job satisfaction rates, as a recent study shows (Diehl, Richter, & Sarnecki, 2018). Since job satisfaction is intrinsically connected to the turnover intention., it will be reasonable to say that power distance also defines the specified variable significantly (Diehl et al., 2018). The research results indicate that power distance, in fact, can shape the levels of organizational justice and the ways in which it is executed (Diehl et al., 2018). As a result, power distance has an indirect yet very powerful effect on turnover intention in staff members. The concept of power distance is typically measured by the characteristics such as “employees’ involvement in decision-making, the degree of openness of leaders toward suggestions, how employees react to the decision of the leader,” and several other factors that may be company-specific (Zagladi, Hadiwidjojo, & Rahayu, 2015, p. 43). Therefore, it can be assumed that power distance within an organization is correlated to the degree of employee engagement and, therefore, the levels of turnover intent.

At present, there exists an ample body of research on the relationship between power distance and employees’ job satisfaction. Lin, Wang, and Chen (2011) discuss the role of power distance orientation in mitigating the adverse effects of abusive supervision. As defined by Lin et al. (2010), abusive supervision is a prolonged emotional and psychological mistreatment of subordinates that often results in job dissatisfaction and higher turnover intention rate. After testing two independent samples, Lin (2011) established that a person’s power distance orientation, or the degree to which he or she accepts inequalities between classes, served as a protective factor against the destructive impact of power distance orientation.

Although it might seem that lower power distance immediately entails a drop in the turnover intention, the relationship between these two variables appears to be more nuanced. Namely, once power distance is diminished to its critical level, staff members lose the sense of responsibility that allows them to meet the set expectations accordingly (Zagladi et al., 2015). The observed phenomenon is quite characteristic of the organizations that tend to have rather vague corporate philosophy and values (Diehl et al., 2018). However, the threat of failing to balance power distance with the needed extent of control is quite tangible for any organization. To address the problem of power distance and the extent of the turnover intention in staff members, a detailed assessment of the key factors defining employees’ behaviors and attitudes in the workplace will be needed. The assessment in question will have to be company-specific so that the evaluation of key influences on the levels of power distance could be accurate and profound.

Nevertheless, the focus on creating a harmonious and comfortable workplace environment for employees should remain a priority for managers. Thus, the levels of satisfaction among the target audience will increase, which, in turn, will affect their turnover intentions negatively (Anand, Vidyarthi, & Rolnicki, 2018). Specifically, the power distance approach will have to be rooted in the idea of mutual respect. By showing employees that they are valued and that their place in the corporate hierarchy will always be respected and appreciated, an organization will invest in the development of an essential asset.

The fact that power distance will be assessed as the moderator in the relationships between the main variables, which are organizational justice and the turnover intention, also implies that a strategy for addressing the problem of the rising turnover intention can be built using the mediating influence of an increase in employees’ role within the organization. In the environment of the Chinese culture, the specified change may imply increasing the extent to which staff members participate in decision-making, as well as the level of their initiative during brainstorming and other activities associated with problem-solving.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework of this research will center the phenomenon of the turnover intention as the main dependent variable that will have to be examined in different settings. Therefore, apart from the correlation between different types of organizational justice and the turnover intention, the causation between the specified factors will be identified.

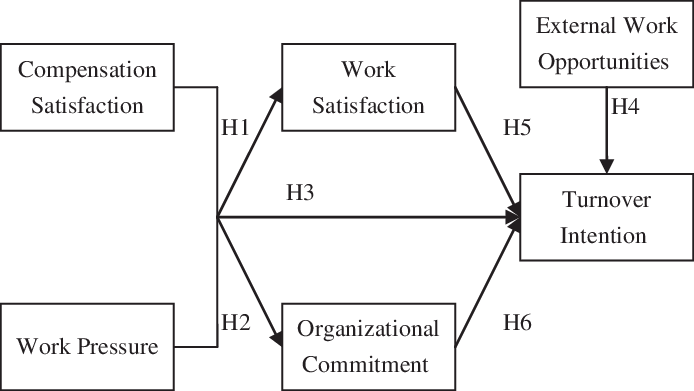

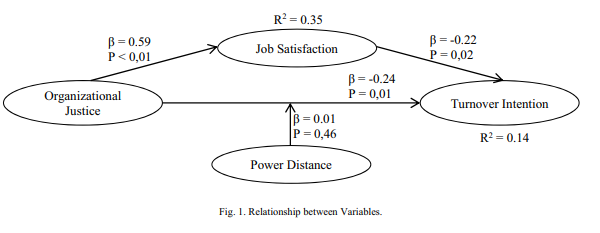

In order to explore the phenomena at hand, the conceptual framework suggested by Chen et al. (2014) will be needed. Specifically, the connection between the factors such as job satisfaction, workplace pressure and the resulting threat of the workplace burnout, the presence of external workplace opportunities, and the levels of organizational commitment as the main influences on the turnover intention will be considered (see Fig. 1). The proposed framework will shed light on the factors that facilitate the emergence of attitudes leading to turnover intention development.

In order to examine the correlation between the variables under the analysis, namely, the presence of organizational justice as a whole, one will need the conceptual framework that incorporates the key factors listed above and unifies them into a cohesive notion of organizational justice at its multiple levels. Therefore, the framework offered by Zagladi et al. (2015) could be seen as a more suitable suggestion. Specifically, the opportunity to consider the connection between the key variables of this research, namely, organizational justice in its three key iterations, and the turnover intention, will become possible.

List the Hypotheses

As explained above, this study seeks to analyze the relationship between organizational justice and the turnover intention in staff members. Therefore, the following hypotheses will be presented in this research:

- Hypothesis A: The correlation between organizational justice and turnover intention is negative.

- Hypothesis B: The correlation between distributional justice and turnover intention is negative.

- Hypothesis C: The correlation between procedural justice and turnover intention is negative.

- Hypothesis D: The correlation between interactional justice and turnover intention is negative.

References

Adams, J. S., Towards an Understanding of Inequity [J]. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1963, 67(5): 422-436.

Akram, T., Lei, S., Haider, M. J., Hussain, S. T., & Puig, L. C. M. (2017). The effect of organizational justice on knowledge sharing: Empirical evidence from the Chinese telecommunications sector. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2(3), 134-145.

Anand, S., Vidyarthi, P., & Rolnicki, S. (2018). Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviors: Contextual effects of leader power distance and group task interdependence. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(4), 489-500.

Beugre, C. I). (1996). Analyzing the effect of perceived fairness on organiza- tional commitment and workplace aggression. Unpublished dissertation, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, School of Management, Troy, NY.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negofiafion in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43-55). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Bramoullé, Y., & Goyal, S. (2016). Favoritism. Journal of Development Economics, 122, 16-27.

Chen, M. L., Su, Z. Y., Lo, C. L., Chiu, C. H., Hu, Y. H., & Shieh, T. Y. (2014). An empirical study on the factors influencing the turnover intention of dentists in hospitals in Taiwan. Journal of Dental Sciences, 9(4), 332-344.

Cho, J., Lee, H. E., & Kim, H. (2019). Effects of communication-oriented overload in mobile instant messaging on role stressors, burnout, and turnover intention in the workplace. International Journal of Communication, 13, 21.

Cropanzano, R., Prehar, C. A., & Chen, P. Y. (2002). Using social exchange theory to distinguish procedural from interactional justice. Group & Organization Management, 27(3), 324-351.

Diehl, M. R., Richter, A., & Sarnecki, A. (2018). Variations in employee performance in response to organizational justice: The sensitizing effect of socioeconomic conditions. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2375-2404.

Folger, R., & Greenberg, J. (1985). Procedural justice: An interpretive analysis of personnel systems. Research in personnel and human resources management, 3(1), 141-183.

Greenberg, J. (1993). The social side of fairness: Interpersonal and informal classes of organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the work- place: Approaching fairness in human resource management (pp. 79- 103). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Haghighinezhad, G., Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F., Ashktorab, T., Mohtashami, J., & Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M. (2019). Relationship between perceived organizational justice and moral distress in intensive care unit nurses. Nursing Ethics, 26(2), 460-470.

Hosmer, L. T., & Kiewitz, C. (2005). Organizational justice: A behavioral science concept with critical implications for business ethics and stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 67-91.

Jiang, Z., Gollan, P. J., & Brooks, G. (2017). Relationships between organizational justice, organizational trust and organizational commitment: a cross-cultural study of China, South Korea and Australia. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(7), 973-1004.

Jin, W. M., Zhang, Y., & Wang, X. P. (2015). Job burnout and organizational justice among medical interns in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 6, 539.

Kerse, G., & Babadağ, M. (2018). I’m out if nepotism is in: The Relationship between nepotism, job standardization and turnover intention. Ege Akademik Bakis, 18(4), 631-644.

Lambert, E. G., Liu, J., & Jiang, S. (2018). An exploratory study of organizational justice and work attitudes among Chinese prison staff. The Prison Journal, 98(3), 314-333.

Lim, A. J. P., Loo, J. T. K., & Lee, P. H. (2017). The impact of leadership on turnover intention: The mediating role of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 1(1), 27-41.

Liu, B., Liu, J., & Hu, J. (2010). Person-organization fit, job satisfaction, and turnover intention: An empirical study in the Chinese public sector. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 38(5), 615-625.

Liu, W., Zhao, S., Shi, L., Zhang, Z., Liu, X., Li, L.,… & Fan, L. (2018). Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 8(6).

Lin, W., Wang, L., & Chen, S. (2013). Abusive supervision and employee well‐being: The moderating effect of power distance orientation. Applied Psychology, 62(2), 308-329.

McFadden, K., & Altamirano, M. A. (2020). Situational factors and increased workplace burnout: A study of influences affecting current younger employees. Nurturing Collective Knowledge and Intelligence: Social Phenomena and Implications for Practice, 2(1), 45.

Pillai, R., Williams, E. S., & Tan, J. J. (2001). Are the scales tipped in favor of procedural or distributive justice? An investigation of the US, India, Germany, and Hong Kong (China). International Journal of Conflict Management, 12(4), 312-332.

Price, J. L. (1975). A theory of turnover. Labor turnover and retention, 51-75.

Price, J. L., & Bluedorn, A. C. (1980). In D. Dunkerley & G. Salaman. The international yearbook of organizational studies 1979, 217-236.

Sokhanvar, M., Hasanpoor, E., Hajihashemi, S., & Kakemam, E. (2016). The relationship between organizational justice and turnover intention: A survey on hospital nurses. Journal of Patient Safety & Quality Improvement, 4(2), 358-362.

Sun, I. Y., Wu, Y., Hu, R., & Farmer, A. K. (2017). Procedural justice, legitimacy, and public cooperation with police: does western wisdom hold in China? Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 54(4), 454-478.

Tata, J., Fu, P. P., & Wu, R. (2003). An examination of procedural justice principles in China and the US. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20(2), 205-216.

Tourani, S., Khosravizadeh, O., Omrani, A., Sokhanvar, M., Kakemam, E., & Najafi, B. (2016). The relationship between organizational justice and turnover intention of hospital nurses in Iran. Materia Socio-Medica, 28(3), 205.

Wong, Y. T., Ngo, H. Y., & Wong, C. S. (2002). Affective organizational commitment of workers in Chinese joint ventures. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(7), 1-10.

Yean, T. F., & Yusof, A. A. (2015). Organizational Justice: A conceptual discussion. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, pp. 798-803.

Zagladi, A. N., Hadiwidjojo, D., & Rahayu, M. (2015). The Role of job satisfaction and power distance in determining the influence of organizational justice toward the turnover intention. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 211, 42-48.

Zhang, Y., & Feng, X. (2011). The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC health services research, 11(1), 235.