Acute Patient Assessment

Emergency Departments are dynamic healthcare settings in which time and effectiveness pose significant challenges to the delivery of the necessary level of care. Unlike other hospital wards, where nurses will have more opportunities to efficiently conduct patient assessments, acute settings require appropriate time management skills in addition to assessing and observing patients according to the established rules of practice.

In the current assignment, the role of a nurse in conducting the assessments of acutely ill patients admitted to Emergency Departments will be analysed. This goal can be achieved through following several steps. First, it is essential to provide a description of professional nursing experience regarding the care for a specific patient at a certain time in practice. Second, the undertaken evaluations will be discussed in relation to the appropriate physiology measures, and the break-down of the performed ABCDE assessment will be presented. Lastly, the management of the chosen patient by the nurse will be critically discussed to find positive and negative aspects of the efficiency and the quality of administered care.

Nursing Experience: An Appendicitis Patient

Acute appendicitis is almost the most common conditions with which patients are admitted to Emergency Departments (ED). In my practice as a nurse in an ED, I was responsible for assessing a patient who showed insignificant signs of appendicitis but experienced enough discomfort to refer to a care provider. The patient, Ms. J, was a 25-year-old woman who reported having frequent abdominal pains for a week. Her manifestations of appendicitis were not evident and were hard to diagnose, especially due to the occurrence of 20% of normal appendix being removed during appendicectomies.

According to Burton-Shepherd (2014), the symptoms of appendicitis can have a variety of diagnoses; however, failing to spot the condition can lead to a range of serious consequences. The first sign of appendicitis is the dull pain located in the navel or the upper abdomen. This pain becomes sharper when it travels to the lower right part of the abdomen. The complexity of the sign is associated with the fact that the pain can also be present in the upper abdomen, rectum, or in the back. Nausea, vomiting and fever that accompany pain also point to possible appendicitis. In some cases, patients can report difficulties and pain during urination, diarrhoea or constipation accompanied by gas, or inability to pass gas.

The patient, Ms. J, admitted to the Emergency Department did not have a fever, nor did she report any nausea or vomiting. Over the past several days, she has been experiencing dull and sometimes severe pain in the lower right abdomen (quadrant), the back, as well as sometimes in the lower left quadrant (Maxton & Butterworth 2018). Her appetite did not differ from usual habits; however, she did experience difficulties passing gas and constipation.

An important sign to mention is that the pain sometimes transferred to the ovarian area, which made the patient suspect cysts. When she referred to her gynaecologist with the complaints about the pain, she was advised to visit the ER for suspected appendicitis because her ovaries were healthy. Critically, these symptoms point to the high possibility of appendicitis, and it was my responsibility as a nurse to prevent the exasperation of the pain symptoms, administer pain medication if needed, as well as to conduct a set of assessments to allow the department to proceed with a surgical intervention to address appendicitis.

Assessments Undertaken with the Patient

In reference to underpinning physiology, the assessment performed with the patient had to identify the existing obstruction of the appendiceal orifice (Jones & Deppen 2018). Prior to conducting a physical examination of the patient, the nurse performed a CT scan to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis. This assessment was necessary to implement because Ms. J’s symptoms were not evident enough. The nurse consulted a CT specialist on the findings of the scan, which revealed an enlarged appendix (8 mm in diameter), the thickening of the appendiceal wall (2.5 mm) and the enhancement of the appendiceal wall (Jones & Deppen 2018).

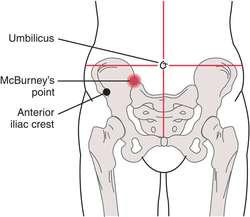

To ensure that the patient had appendicitis, the physical assessment was performed. The most likely physical finding of appendicitis is associated with the tenderness of the abdomen, which takes place in the majority of instances (95% of acute cases of the condition). It was expected that the patient would find the lateral decubitus position with the flexion of the hip as the most comfortable since the pain would reduce and cause less pain. Overall, the abdomen would be soft with tenderness localised at and around the McBurney’s point (Figure 1). The test revealed both localised pain and tenderness in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen.

The patient was expected to be flushed, with the specific symptom of a dry tongue accompanied by hepatic fetor (the peculiar odour of the breath). When performing the assessment of Ms. J, the examination of her abdomen ultimately revealed tenderness, pain and the muscular rigidity in the right iliac fossa. Also, the assessment looked for rebound tenderness without eliciting additional pain in order not to distress the patient (Talley & O’Connor 2018).

This pointed to the high likelihoods of appendicitis diagnosis, During the assessment, the movement was uncomfortable for the patient under examination, and when she asked to cough, she felt severe pain in the right iliac fossa, as expected in most cases of appendix inflammation (White, MacDonald, Johnson & Rudralingham 2014). From a critical perspective, the assessment was necessary not only for diagnosing appendicitis but also for finding any underlying problems that have contributed to its occurrence.

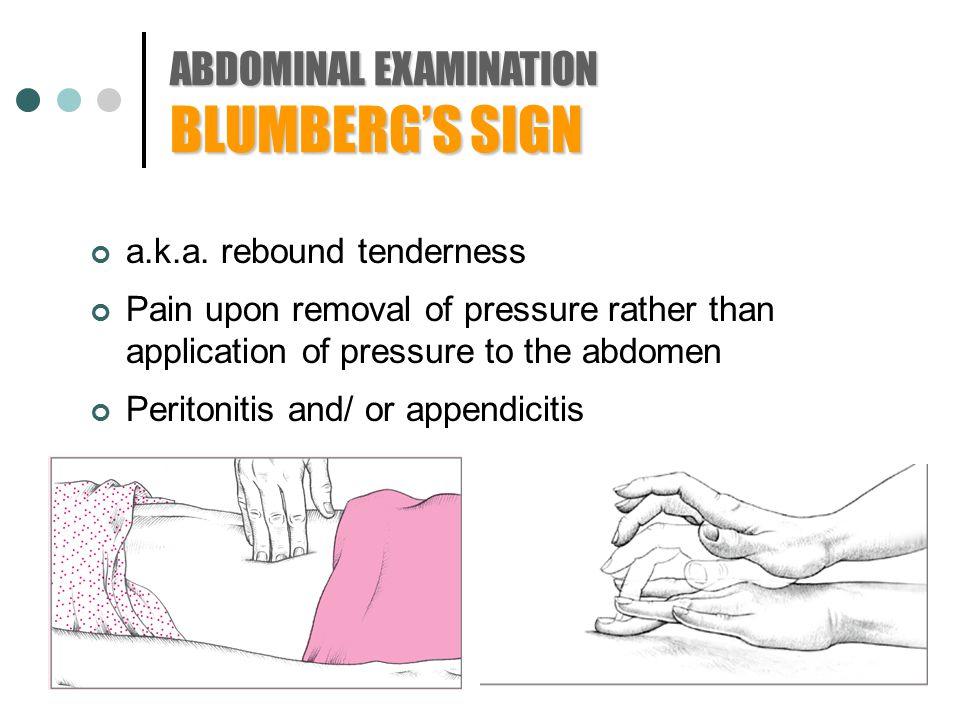

During the physical assessment, the voluntary muscle guarding of the light lower quadrant precedes the tenderness in the right abdomen. Blumberg’s sign was used during the assessment to look for the signs of peritonitis (Petroianu 2012). The procedure implied the slow compression of the abdominal wall and then its rapid release (Figure 2). A positive sign (the presence of appendicitis) indicated the presence of pain once the pressure was removed.

After the assessment using Blumberg’s sign was performed, Rovsing’s sign was used. The sign is elicited through the pushing on the abdomen in the left lower quadrant from the abdomen, which is far away from the appendix (Goodman & Snyder 2013). This is necessary for stretching the peritoneal lining to elicit pain in any location in which the muscle is irritated by the peritoneum. A positive Rovsing’s sign will show that the patient’s pain is prevalent in the right lower abdomen while the pressure would be elicited in a completely opposite direction.

In addition, Cope’s psoas test was performed to provide another support for the diagnosis of appendicitis. The nurses’ tole was to ask the patient to lie on her left side and extend her knees. The right thigh was held by the examiner while the hip was passively extended. A positive psoas sign would indicate abdominal pain due to stretching and contraction.

In Cope’s obturator test, the patient was asked to lie on her back with hips and knees flexed at a ninety-degree angle (Byrne et al. 2017). The nurse held the knee with one hand and the ankle with another. The hip was internally rotated by means of moving the ankle from the patient’s body so that the knee would move inward. The reported pain in the abdomen pointed to the likely diagnosis of appendicitis.

In addition to the mentioned procedures used by the nurse, the ABCDE approach was used. Its underlying principle refers to completing an initial assessment of a patient in a critical condition and re-assess him or her regularly (Sunaryo 2015). The aims of the ABCDE assessment is enabling appropriate interventions, communicate effectively across departments and keep patients’ health on the necessary level to buy time for future treatment and diagnosis. The break-down of the ABCDE assessment performed by the nurse in relation to the appendicitis patient is presented in the Appendix.

Discussion of the Patient’s Management

Appendicitis is a common diagnosis that can occur in patients of all ages, with the incidence higher in between 10 and 19 years (Mengesha & Teklu 2018). The “diagnostic criteria for acute appendicitis rely on the documentation of the reported recurrent attacks of pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, the measurement of body temperature,” and the physical assessment that includes several tests to identify signs pointing to the possible diagnosis of appendicitis (Mengesha & Teklu 2018, p. 17). In conducting the assessment, a nurse should be especially careful to ensure that all other causes of lower right abdominal pain are eliminated before proceeding with an appendectomy.

The performance of the ABCDE assessment along with Blumberg’s, Rovsing’s, Cope’s psoas and Cope’s obturator tests revealed that despite the symptoms being not as obvious, the patient required immediate appendectomy before the exasperation of her condition (Ahn et al. 2016). After the patient was informed that she would undergo surgery within the next several hours, the nurse was responsible for the following management procedures:

- Escorting the patient to her ward;

- Educating on the procedure and the expected outcomes of appendectomy (Yilmaz et al. 2017);

- Conducting a test for possible pain killer allergies;

- Referring an anaesthesiologist to the patient to perform a pre-surgery evaluation;

- Changing the patient into a gown;

- Communicating with the patient’s family members about the upcoming procedure;

- Responding to patient inquiries.

After the surgery was performed, the nurse was also responsible for postoperative care (Ahn et al. 2016). Since the young woman’s appendix was unruptured, the procedures involved in her further management were relatively simple. The morning after surgery, she was given clear liquids to introduce the intake of solid foods gradually. Pain medication was administered intravenously to ensure quick relief. Regular assessments of the patient’s vital signs were performed alongside with monitoring the process of the incision’s healing (Ahn et al. 2016). Before letting the patient go home, a final ABCDE assessment was performed to evaluate whether the administered clinical interventions improved her condition.

Summary and Conclusion

Cases of appendicitis are a common occurrence in Emergency Departments, and nurses should be prepared to address them immediately due to the high risks of severe damage to the organism. An appropriate set of assessments has been developed to ensure that a patient does have an inflamed appendix and requires surgical treatment (Gadiparthi & Waseem 2018). The combination of the standardised Blumberg’s, Rovsing’s, Cope’s psoas and Cope’s obturator tests will eliminate the likelihood of other conditions’ occurrence while the ABCDE assessment will give a nurse an overall understanding of a patient’s condition and define further management steps.

In the case of the patient who presented to the ED with mild symptoms of appendicitis, the physical examination was the most effective tool in ensuring that further surgical intervention would be needed. Since the patient did not have such signs fever, nausea, diarrhoea and other accompanying symptoms and only reported both dull and sharp pain in different areas around the abdomen, the case was more complex than the usual instances of appendicitis, showing that nurses in the ED should be prepared to meet the needs of as many patients as possible. After the correct diagnosis had been made, the patient underwent an appendectomy and was administered further medication for pain relief and subsequent recovery.

Appendix

History: Ms. J, 25 years old, female. She was previously diagnosed with hypothyroidism, anaemia and citrus and seasonal allergies. The patient had a family history of thyroid dysfunction, which runs on her mother’s side. The patient’s grandmother had type 2 diabetes while her mother has undergone thyroid tumour surgery. At the moment, Ms. Takes hormonal contraceptive pills and occasional antihistamines for allergies. Ms. J takes blood tests every three months to monitor the levels of thyroxine and triiodothyronine hormones.

Patient’s ABCDE Assessment

First Step

Upon the arrival to the Emergency Department with the complaint of pain in the right lower abdomen, the patient was referred to a nurse who started the assessment. The nurse asked the patient about her well-being and observed the following signs: heavy breathing, pale skin, cold hands and feet, dry mouth and tongue, the lack of concentration and exhaustion. An intravenous cannula was inserted as well as blood for testing was taken. The patient was responsive and did not show signs of a critical condition.

Airway (A)

No signs of airway obstruction were determined as the patient did not show any signs pointing to it: no see-saw respirations or the use of accessory respiratory muscles. Breath sounds at the mouth and nose were present. No resuscitation methods were needed; for instance, the patient did not present the need for the UK-supported bag-mask ventilation used for fiving two breaths after every thirty compression (Newell, Grier & Soar 2018).

Breathing (B)

The measured respiratory rate was 24 breaths per minute, which is higher than normal. The pattern of respiration was irregular: in one minute the patient did not exhibit any signs of abnormal breathing while in some cases heavy breathing was present. The patient explained this factor by reporting that she was worried and anxious to come to the ED. No deformities of the chest or limitations of the diaphragmatic movement were noted. To percussion, the chest did not reveal any hyper-resonance or dullness.

Circulation (C)

During the assessment, it was revealed that the patient’s hands were pale (her fiancé indicated that her entire skin tone was paler than normal). Both hands and feet were cool; while the patient said that she got cold in the car, the paleness along with lowered body temperature pointed to low blood circulation. The test for the capillary refill time showed that it took the skin 4 seconds to return to its original colour. No signs of underfilled or collapsed veins were present; the blood pressure was low: 89/60 mm Hg and the pulse was 60 BPM. No heart murmurs or pericardial rubs to auscultation were present; the heart sounds were easy to hear. The patient was administered fluids to increase blood pressure; expert help was sought in order to confirm the further management of the condition.

Disability (D)

Normal size, equality and reaction to the light of pupils. The patient passed the AVPU test: was alert, responded to vocal and painful stimuli. Hypoglycaemia was eliminated from the diagnosis through the administration of the finger-prick method of testing. The patient was allowed to lie down on a wheeled stretcher in order to wait to be transported in an examination room.

Exposure (E)

The full exposure of the body was not necessary for the assessment of the patient. She was then transported to an examination room for the performance of the Blumberg’s, Rovsing’s, Cope’s psoas and Cope’s obturator tests. Since the patient reported being cold several times, the nurse made sure to provide her with warm blankets and pillows. Warm drinks were avoided due to the risks of abdominal pain’s exasperation.

Reference List

Abdominal examination n.d. Web.

Ahn, S, Lee, H, Choi, W, Ahn, R, Hong, J-S, Sohn, C, Seo, D, Lee, Y-S, Lim, K & Kim W 2016, ‘Clinical importance of the heel drop test and a new clinical score for adult appendicitis’, PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 1-10.

Burton-Shepherd, A 2014, ‘Diagnosing appendicitis,’ Independent Nurse, vol. 6, pp. 17-18.

Byrne, C, Alkhayat, A, O’neill, P, Eustace, S & Kavanagh, E 2017, ‘Obturator internus muscle strains’, Radiology Case Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 130-132.

Gadiparthi, R & Waseem, M 2018, Appendicitis, paediatric. Web.

Goodman, C & Snyder, T 2013, Differential diagnosis for physical therapists, Elsevier, St. Louis.

Jones, M & Deppen, J 2018, Appendicitis. Web.

Maxton, D & Butterworth, J 2018, Lower abdominal pain in women. Web.

McBurney’s point n.d.. Web.

Mengesha, M & Teklu, G 2018, ‘A case report on recurrent appendicitis: an often forgotten and atypical cause of recurrent abdominal pain’, Annals of Medicine and Surgery, vol. 28, pp. 16-19.

Newell, C, Grier, S & Soar, J 2018, ‘Airway and ventilation management during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and after stressful resuscitation’, Critical Care, vol. 22, pp. 190-211.

Petroianu, A 2012, ‘Diagnosis of acute appendicitis’, International Journey of Surgery, vol. 10, pp. 115-119.

Sunaryo, E 2015, The effect of the ABCD assessment method and an educational session on nursing physical assessment on the general ICU at Dr Sardjito Hospital, Special Region Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Web.

Talley, N & O’Connor, S 2018, Clinical examination: a systematic guide to physical diagnosis, Elsevier, Chatswood.

White, E, MacDonald, L, Johnson, G & Rudralingham, V 2014, ‘Seeing past the appendix: the role of ultrasound in right iliac fossa pain’, Ultrasound, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 104-112.

Yilmaz, E, Soyder, A, Aksu, M, Bozdağ, A, Boylu, Ş, Edizsoy, Ş & Takindal, M 2017, ‘Contribution of an educational video to surgical education in laparoscopic appendectomy’, Turkish Journal of Surgery, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 237-242.