Biological Basis

The concept of personal genomics can be defined as the area of genomics which addresses the issues of gene sequencing, creating a personal eTQL genomic profile, and other aspects of obtaining essential information from one’s genome (Martinez-Jimenez et al., 2015). Particularly, the concept implies that the order of four crucial elements, i.e., “adenine, guanine, cytosine and thymine” (Gupta, 2016, p. 359) should be determined in the process.

An accurate identification of the nucleotide sequence, also known as the DNA strand basis, can be viewed as the ultimate goal of the gene sequencing process. The approach referred to as the “single-nucleotide addition (SNA)” (Goodwin, McPherson, & McCombie, 2016, p. 335) method of DNA sequencing needs to be brought up as one of the most common tools for carrying out the genome sequencing process.

However, when it comes to discussing the approaches that have only recently been introduced into the context of the contemporary genetic studies, one must mention the frameworks known as Sequencing by Hybridization (SBH), Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), Sequencing by Ligation (SBL), Pyrosequencing, Nanopore DNA Sequencing, Ion Torrent semiConductor Sequencing, Illumina (Solexa) Sequencing, Transmission Electron Microscopy for DNA Sequencing, and Nanopore Sequencing (Yadav, Shukla, Omer, Pareek, & Singh, 2014). The identified approaches imply the analysis of rather long DNA sequences, as well as the entire chromosome (Martinez-Jimenez et al., 2015).

A DNA structure includes two primary elements, i.e., a sugar phosphate backbone and base pairs containing Adenine, Thymine, Guanine, and Cytosine (Goodwin et al., 2016). Its functions are restricted to carrying essential genetic information. The resulting gene expression defines the functioning of an organism, e.g., the production of specific secretions, etc. Using the information contained in a DNA will allow managing hereditary diseases, preventing severe health outcomes, and fighting the health threats that are currently considered impossible to address.

The process of genome sequencing may vary depending on the approach chosen by a researcher. To analyze the process, one may consider Nanopore Sequencing as one of the latest innovations in the personal genomic research. The process implies that the DNA strands should be heated and that the reaction should occur in the presence of a substance known as dideoxyribonucleotide. Dideoxyribonucleotide is quite similar to DNA, yet it does not have the 3′ hydroxyl group.

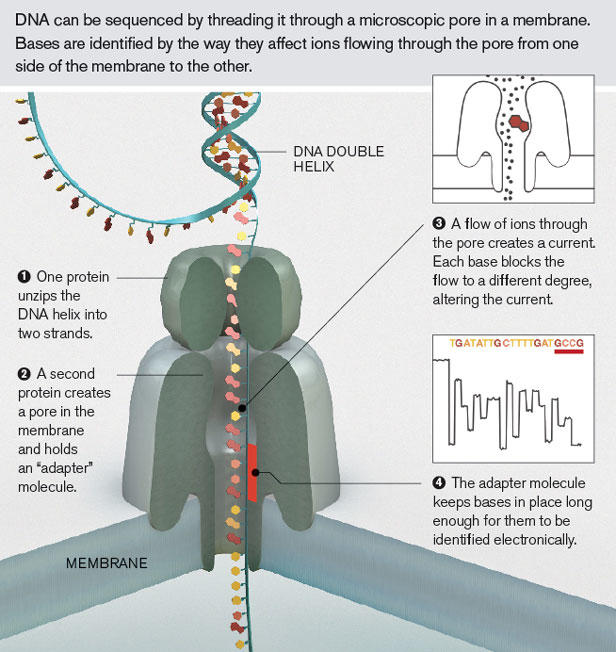

The DNA strand is replicated with dideoxy-T serving as the catalyst. The entire process implies that the DNA should be threaded through a pore in a membrane. First, a protein unzips the DNA helix so that it could be represented by two strands. Afterward, the second protein creates a pore in the membrane while holding the molecule that serves as an adapter and, therefore, does not allow it to close. Ions flow through it, thus, creating a current, which is altered by two base blocks (Goodwin et al., 2016). Finally, the adapter molecule keeps the pore open for the amount of time required to identify the ions and carry out an all-embracive analysis thereof, as Figure 1 below shows.

By adopting the technique described above, one becomes capable of decomposing and reading DNA bases successfully. As a result, the unique characteristics of a patient’s genetic makeup can be identified. Particularly, the propensity toward developing certain diseases and disorders can be determined.

Social and Ethical Implications

When considering the effects of deploying personal genomics as a standard tool for addressing hereditary diseases, one is likely to encounter a range of ethical issues, the threat of genetic discrimination being the key one. By definition, generic discrimination implies a scenario in which the attitude toward one patient is strikingly similar to another one because of the ostensible gene mutations observed in one of the patients.

Viewing the needs of the patient that seems to have gene mutations as superior to the ones of the patient that has not undergone a genomic analysis or does not have the specified mutations is viewed as a possible form of discrimination that may infringe some patients’ rights (Hallowell, Hall, Alberg, & Zimmern, 2013).

Therefore, it is possible that the use of personal genomic analysis results as the means of prioritizing patients’ needs and defining some patients’ concerns as inferior to the ones of other customers will be observed in the context of healthcare facilities once a genomic analysis becomes a common service. On the one hand, there are legitimate reasons for the identified concern. Indeed, with the promotion of personal genomics as an essential tool in determining the genetic makeup of patients, some of the latter, whose health issues will have been known to a therapist, are likely to be seen as the top priority.

In other words, the risks of applying it to manage the needs of patients in the context of a healthcare facility are moderate. On the other hand, the specified tool is likely to allow preventing the instances of serious health problems, the development of severe consequences, and, possibly, reducing the death toll significantly. Thus, its benefits are quite numerous. Therefore, the use of personal genomics seems quite sensible.

Moreover, the threat of overlooking the needs of people from underdeveloped states will become tangible with the enhancement of personal genomics tools. Indeed, because of the cost of the services, they are likely to be affordable only to people with a rather high income. The risks of failing to address the needs of the members of poor communities are very high in the specified scenario. Therefore, the strategies for reducing the costs for the procedures relate dot personal genomics will have to be deployed. For instance, searching for the ways of financing healthcare facilities providing personal genomics services in low-income areas will have to be considered (Hallowell et al., 2013).

Personal Viewpoint

It seems that the application of personal genomics tools as the methods of determining the presence of genetic disorders in patients must be deployed in the context of the modern healthcare environment. The adoption of the specified framework to locate possible issues in people’s physiological and psychological development is, therefore, completely legitimate. Despite the fact that its current affordability leaves much to be desired, as well as the fact that it may compel therapists to put the needs of certain patients in front of the needs of others, the application of personal genomics tools may provide the results that will help save people’s lives.

Consequently, the further promotion of personal genetics must be enhanced in the context of the contemporary healthcare environment. Financial resources must be provided to equip healthcare facilities with the devices that are required to carry out a personal genomics analysis. For instance, the tools for carrying out bioinformatics-related processes will have to be incorporated into the set of devices used by healthcare practitioners.

It should be noted, though, that the identified changes will also require placing a powerful emphasis on the promotion of patient and nurse education. Customers will have to be instructed about the specifics of the procedures, their effects, and the health opportunities that they provide. Nurses, in turn, will need to acquire the skills that will allow them to manage the processes related to a personal genomic analysis successfully. As a result, a gradual improvement in patient outcomes is expected.

References

Goodwin, S., Mcpherson, J. D., & Mccombie, W. R. (2016). Coming of age: Ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17(6), 333-351. Web.

Gupta, P. D. (2016). Nanopore technology: A simple, inexpensive, futuristic technology for DNA sequencing. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 31(4), 359-360. Web.

Hallowell, N., Hall, A., Alberg, C., & Zimmern, R. (2013). Revealing the results of whole-genome sequencing and whole-exome sequencing in research and clinical investigations: Some ethical issues. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(4), 317-321. Web.

Martinez-Jimenez, M. I., Garcia-Gomez, S., Bebenek, K., Sastre-Moreno, G., Calvo, P. A., Diaz-Talavera, A.,… Blanco, L. (2015). Alternative solutions and new scenarios for translesion DNA synthesis by human PrimPol. DNA Repair, 29, 127-138. Web.

Shaffer, A. (2012). Nanopore sequencing. MIT Technology Review. Web.

Yadav, N. K., Shukla, P., Omer, A., Pareek, S., & Singh, R. K. (2014). Next generation sequencing: Potential and application in drug discovery. The Scientific World Journal, 14, 1-7. Web.