Introduction

Human factors play a significant role in the effectiveness of machines, and so are cases with airplanes. However, the same elements are also responsible for the failures associated with devices, and airplanes are no exception. Based on investigations by the National Transport and Safety Board (NTSB) on air accidents, Strauch (2017) showed that more than 87 percent of all chartered aircraft accidents are, at least in part, attributed to errors by pilots. In general and private aviation, the leading cause of aircraft control loss is associated with pilot error, and commercial airlines are subject to the same mistakes (Sutthithatip et al., 2021). The flight crew is always the first and the last defense line against any accident in the aviation industry and must put aside every disastrous mechanical breakdown. In addition to the lives of the passengers on the line, so are the lives of flight crew members (Dhillon, 2017). Nonetheless, most airlines pressure crew members and pilots, resulting in an increased likelihood of human error in operations.

Due to negligence by airline corporates, there have been cases of fatigued o improperly trained pilots. With this, not only are the lives of the passengers put at risk but also those of the crew members and the pilot (Boyd and Dittmer, 2016). The significance of this archival research is to study the aircraft accidents attributed to pilot error. According to the NTSB, the factors associated with the pilot error in this study are lousy weather, inclusive of turbulences and carelessness involving domestic air careers within the United States between 1983 and 2002.

Case study Background

Principally, human factors study the relationship between the individuals operating machines and the machines themself. The interaction between these two players is more complicated than in many other fields in the aviation industry. Using the 2000 Southwest Airlines Flight 1445 accident, for example, the flight from Las Vegas to Burbank, California, crashed due to human error (Baum Hedlund, n.d). At the landing approach, despite the warning signal alerting both the first officer and the pilot on the differences between the descent angle and flight speed to the glide path, the two ignored the warnings (Aghaeiet al., 2016). The ignorance resulted in the airplane crashing through a wall and a fence by overrunning them and coming to a rest in the nearby neighborhood, which was a near miss from gas station pumps.

Since the early 1980s, commercial aviation has encountered significant changes. However, with the increase in the number of commercial flights, the demand for pilots has been on the rise. The same has been the case with many airports and air traffic controllers (Baker et al., 2008). The associated changes in commercial aviation have been known to incorporate advanced use of computers, in operations, among other technological improvements that have impacted the way pilots perform their tasks (Sun et al., 2017). Flight simulators have become the majorly relied form of pilot training while crew members’ interaction and communication have been enhanced using crew resource management (Leung and Rife, 2017). Further, Baker et al. (2008) show that since 1997, 14 CFR Part 135 regulators have been governing most commuter flights requiring pilots to fly under stricter Part 121 regulations. The more stringent Part 121 laws had been previously applicable only to 30 or more passenger aircraft.

Several commercial aviation changes have been utilized to minimize the possibility of human error-related accidents from happening. Human errors, specifically pilot errors, have long been considered the most contributor to air travel fatalities (Temme et al., 2018). Intending to determine whether the researchers had achieved the beneficial effect of the study, Baker et al. (2008) examined the question of whether the pilot error was declining. The researchers examined the changes or characteristic significance in the two decades between 1983 and 2002. Therefore, the primary objective of the study then became to identify the temporal trends in pilot error patterns and prevalence alongside associated factors in air career accidents.

Databases

This archival study retrieved information from various aviation databases, including the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) and the Advanced Technologies and Aerospace databases. The other incorporated database in retrieving the information employed in the archival study was the National Transportation Safety Board’s Aviation Accidents Database. With the research centered on factors associated with the pilot error by factoring in bad weathers, inclusive of turbulences and carelessness, the affiliated databases have given diversified information between 1983 and 2002. With each data type on the factors that cause human error in aviation, an illustration will be later provided, while the effects of the errors will be further discussed.

Methodology

Procedure

From the onset, the research was an online exploration of pilot errors in air carrier accidents resulting in the utilization of AIAA, ATA, and NTSB Aviation Accidents databases. With the investigation centered on how human errors cause aviation accidents, the gathered information was diversified between two decades, 1983 and 2002, for each error. According to the report by the NTSB Aviation Accidents, the association between pilot error and air carrier accidents for the studied period, as published in 2008, was utilized in the research. From various databases, AIAA, ATA, and NTSB Aviation Accidents, the data collected was used to compile this report on the impact pilot error has on the number of accidents between 1983 and 2002.

Further, the report also entails data extracted from AIAA and ATA databases on the relationship between accidents and bad weather, inclusive of turbulences and mishandled wind or runway conditions. Like pilot error, bad weather and mishandled wind or runway conditions had a significant impact on the number of accidents between 1983 and 2002. The research utilizes Microsoft Excel to analyze the gathered information for data analysis purposes. The main limitation associated with the study is adverse reports related to aviation accidents. In the following section, the results obtained and the research outcomes are illustrated.

Results Obtained

Between 1983 and 2002, NTSB associated 604 aviation accidents with human errors, excluding criminal and terrorism actions within domestic air carriers in the U.S. The research included an analysis of 558 casualties, represented by 92 percent of the entire accidents reported by NTSB. There was an exclusion of 39 and seven mishaps from the remaining 46 due to missing information and various reasons. As seen in Table 1, the results showed that within the twenty years, there was an average of 33 mishaps per every one million departures with no significant consistency in longitudinal trends.

Table 1: Pilot error resulting in mishap rates per 10 million flights.

Inclusive of turbulence, bad weather also played a role in the number of accidents in the twenty years. In the 265 cases, representing 47 percent of the accidents, clear air turbulence and mechanical failure resulted in 138 and 117 mishaps, respectively. However, the accidents proportion where lousy weather played a part slightly decreased by 17 percent. Moreover, there were no statistically noteworthy longitudinal trends associated with the conditions.

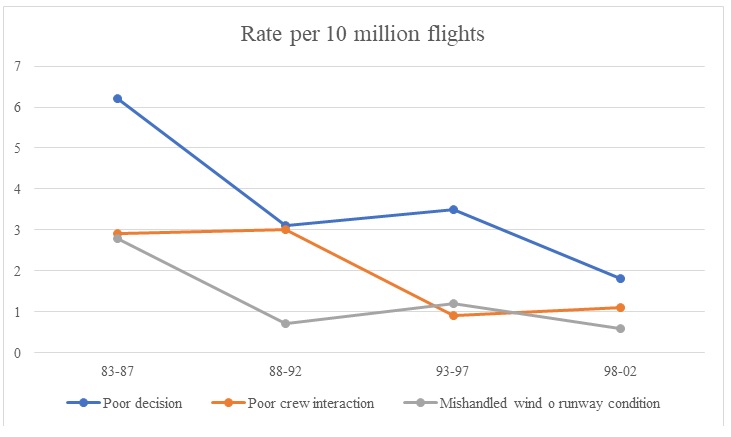

In pilot error-related accidents, it was noted that 180 mishaps happened in the same timeframe representing 32 percent of the cases established in the twenty years. Nonetheless, due to computer and technology advances inclusion, there was a decline in the percentage of accidents attributed to pilot errors. The number gradually declined from 42 percent in the period 1983-1987 to 25 percent in 1998-2002, as seen in Table 2 below, representing an overall 40 percent decrease in the number of mishaps. Moreover, at least two pilot errors in 56 reported accidents, with carelessness topped the list with 26 percent. The other pilot error-related factors were poor decisions at 23 percent, mishandling aircraft kinetics at 21 percent, and poor crew interactions at 11 percent, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 2: Pilot error by number and type.

The case of carelessness is associated with the pilot’s inability to check for hydraulics when reading the checklist before attempting to land the airplane. Due to the absence of hydraulic pressure at the flaps or the landing gear, the DC9 engaged in gear-up landing. There was evidence of poor crew interactions due to hard landing with the subsequent events resulting in an unstabilized approach where the first officer commended the pilot for landing without attempting the go-around. the study found the failure by the pilot to listen to the first officer to the reason for the accidents

In the timeframe the study took place, as evident in Table 1, the accident’s proportion declined from 14.2 to 8.5 per 10 million flights representing a 40 percent decrease in the number of mishaps. However, concerning aircraft kinetics and carelessness, there was no evidence linking the two to the trend in the rates of casualties. As shown in Figure 2, pilot error characterized as poor decisions also declined by 71 percent from 6.2 to 1.8 per 10 million departures compared to poor crew interaction and mishandled wind or runway condition.

In Table 3, the results of the archival study showed that how accidents happened was proportional to the flight phase. With this, pilot error was the most familiar cause of mishaps, between 44 and 64 percentages, at the time of takeoff, landing, final approach, and taxiing. However, when the aircraft was being pushed back from the gate, the pilot error caused 11 percent of the accidents, and 9 percent of the mishaps happened while the airplanes were still.

Table 3: Mishaps attributed to any pilot error.

From Figure 3, there were significant trends associated with the three flight phases. At takeoff, the proportion of accidents encountered a decline from 5.3 to 1.6 per 10 million departures representing a 70 percent decline. On the contrary, the mishaps linked to the aircraft have increased more than twofold from 2.5 to 6. Between the four timeframe categories, accidents attributed to pushback rose from zero to 3.1 between 1983-1987 to 1998-2002.

Conclusion

The exciting aspect of the archival study is linked to how human errors play a significant role in the number of accidents during the time of the investigation. Depending on the flight phase, pilot- error-related factors, and carelessness, the results have shown both an increase and a decline in how pilot error contributed to mishaps in the study period. The example provided, the 2000 Southwest Airlines Flight 1445 accident associated with the flight from Las Vegas to Burbank, California, which crashed due to human error. While the research centered on factors related to pilot error by factoring in bad weathers, inclusive of turbulences, and carelessness, pilot error was the primary cause for the mishaps encountered at the time of the study. The AIAA, ATA, and NTSB Aviation Accidents records have diversified information about aviation accidents between 1983 and 2002. From the results, the recommended is that pilots and their first officers should always have appropriate coordination to minimize possibilities of accidents from happening. Further, proper training is significant in ensuring pilots overcome potential difficulties while in their line of duty.

References

Aghaei, A. S., Donmez, B., Cheng, C. L., Dengbo, H., Liu, G., Plataniotis, K. N., Huei-Yen, W. C.,… Sojoudi, Z. (November 01, 2016). Smart driver monitoring: When signal processing meets human factors: In the driver’s seat. Ieee Signal Processing Magazine, 33, 6, 35-48.

Baker, P. S., Yangdong, Q., George, W, R., & Guohua, L. (2008). Pilot error in air carrier mishaps: Longitudinal trends among 558 reports, 1983-2002. Aviat Space Environ Med, 79(1): 2-6. Web.

Baum Hedlund. (n.d). Human factors in aviation. Web.

Boyd, D., & Dittmer, P. (2016). Accident rates, phase of operations, and injury severity for solo students in pursuit of private pilot certification (1994-2013). Journal of Aviation Technology and Engineering, 6, 1.).

Dhillon, B. S. (2017). Engineering systems reliability, safety, and maintenance: An integrated approach. Boca Raton CRC Press.

Leung, T. J., & Rife, J. (March 01, 2017). Refining fault trees using aviation definitions for consequence severity. Ieee Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, 32, 3, 4-14.

Strauch, B. (2017). Investigating human error: Incidents, accidents and complex systems. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business.

Sun, R., Yuan, Z., Sun, L., Ma, Y., & 2017 4th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS). (August 01, 2017). Analysis of safety trend in civil aviation of China. 852-857.

Sutthithatip, S., Perinpanayagam, S., Aslam, S., Wileman, A., & 2021 IEEE/AIAA 40th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC). (October 03, 2021). Explainable AI in aerospace for enhanced system performance. 1-7.

Temme, M.-M., Tienes, C., & 2018 IEEE/AIAA 37th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC). (September 01, 2018). Factors for pilot’s decision making process to avoid severe weather during enroute and approach. 1-10.