The topic of plate tectonic of the Dominican Republic is extremely important for geology in general. The subject of tectonic plates is also essential for understanding the mechanisms of the Earth’s existence. However, in tectonics, several issues should be studied in more detail. To do this, one should consider the available information in the region from several sources. This basis will form a coherent system of understanding the issue.

In the book Essentials of Geology by Stephen Marshak, the topic of geological processes in tectonics is described in sufficient detail. Hess postulated the seafloor spreading theory, according to which new seafloor emerges at mid-ocean ridges and then spreads symmetrically away from the ridge axis. At deep-ocean trenches, the ocean bottom dips back into the mantle. The lithosphere is divided into separate plates that move around in relation to one another. Plate movement manifests itself in continental drift and seafloor spreading. The majority of earthquakes and volcanoes happen near plate borders, with plate interiors remaining relatively solid and unaltered. Volcanic activity occurs in hot areas at solitary volcanoes. As said in the textbook, “hot spots are places where volcanism occurs at an isolated volcano” (Marshak, 2019b). The volcano travels away from the hot area and dies, and a new volcano erupts over the hot site when a plate moves over it.

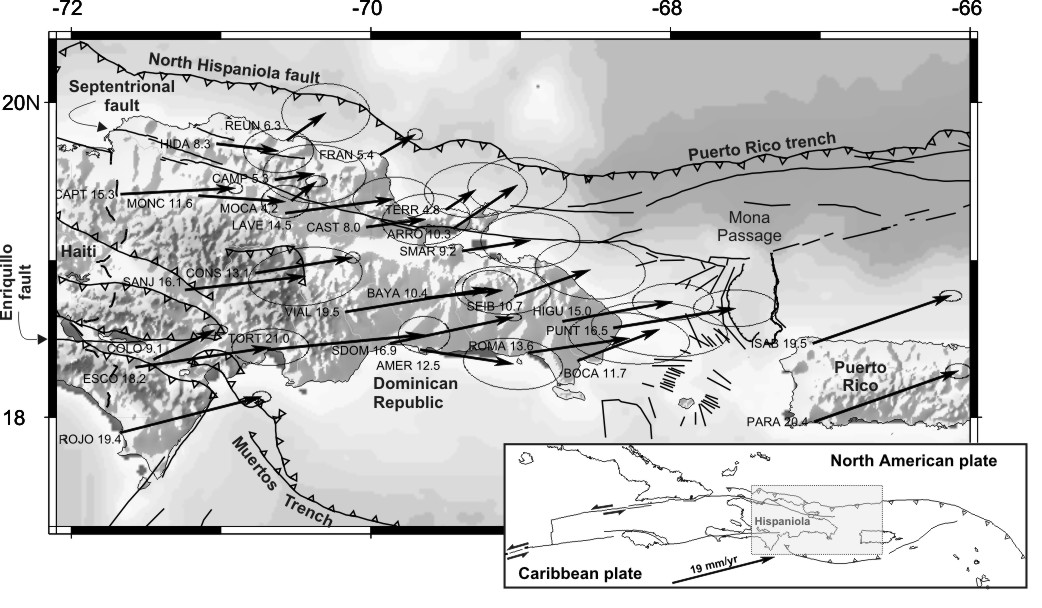

Mantle plumes may be the source of the hot regions. When a buoyant chunk of crust (a continent or an island arc) slides into the subduction zone, convergent boundaries vanish. When this happens, there is a collision. Plate movements are aided by ridge-push force and slab-pull force. Plates shift at a rate of 1 to 15 centimeters every year. These movements can be detected using GPS satellite readings. Summing up, the textbook quite accurately describes the processes taking place on the territory of the Dominican Republic.

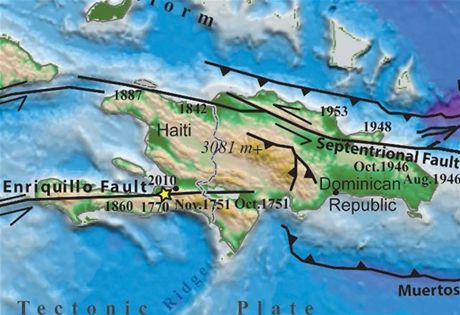

Next, the articles on the subject of plate tectonics with specific details about Dominican Republic should be explored. The deep Puerto Rico Trench formation and a zone of intermediate focus earthquakes inside the subducted slab results in the deep Puerto Rico Trench formation and a zone of intermediate focus earthquakes. Although the Puerto Rico subduction zone can produce megathrust earthquakes, none have occurred in the last century. The most recent possible thrust fault occurrence occurred on May 2, 1787. It was extensively felt across the island, with reported devastation along the northern shore, including Arecibo and San Juan (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). The two strongest earthquakes in this region since 1900 were the M8.0 Sain Hispaniola northern Hispaniola on August 4, 1946, and the M7.6 Mona Passage earthquake on July 29, 1943, both shallow thrust fault earthquakes (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). Thus, the article describes the phenomenon of the earthquakes in Puerto Rico, which is related to the concept of plate tectonics.

A series of left-lateral strike-slip faults bisect in some places. A considerable fraction of the motion is accommodated on the island of Hispaniola. Mainly such incidents took place at the Septentrional Fault in the north and the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden Fault in the south. It takes place between the North American Plate and the Caribbean plate in this region (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). The deadly January 12, 2010, M7.0 Haiti strike-slip earthquake, its attendant aftershocks, and a similar quake in 1770 are the best examples of activity near the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden Fault system (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). In thus fragment, the article the relationship between various earthquakes and their relevance for Puerto Rico case.

It is important to notice that plate boundary curves east and south across Puerto Rico and the northern Lesser Antilles, where the Caribbean plate’s plate motion vector is less oblique than the North and South America plates, resulting in active island-arc tectonics. Along the Lesser Antilles Trench, the North and South America plates subduct towards the west. It takes place beneath the massive Caribbean tectonic plate at a rate of around 20 mm/yr. Inside the subducted plates and throughout the island arc, both intermediate focal earthquakes and a chain of active volcanoes occur due to the subduction. Despite being one of the Caribbean’s most seismically functional areas, just a few of the Lesser Antilles’ earthquakes have been greater in the recent century.

Further west, a large zone of compressive deformation stretches through western Venezuela and central Colombia, trending southwestward. The plate boundary in northern South America is not clearly defined. Although deformation shifts from Caribbean/South America convergence in the east to Nazca and South America convergence in the west (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). Diffuse seismicity characterized by low- to intermediate-magnitude earthquakes of shallow to intermediate depth indicates the transition zone between subduction on the eastern and western borders of the Caribbean plate.

In the eighteenth century, severe earthquakes struck the Enriquillo fault system. In 1701, an earthquake with a magnitude of MI 6.6 struck at the same site as the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and descriptions of the shaking are comparable to those of the 2010 earthquake (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). MI 7.4–7.5 earthquake, which occurred on the eastern end of the fault in the Dominican Republic, began a sequence of big earthquakes that migrated from east to west (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). The shallowly dipping megathrust interface of this plate boundary section was the site of the M8.5 earthquakes (Significant Earthquakes on a Major Fault System in Hispaniola, 2018). The Cocos plate subducts beneath the Caribbean plate along the western coast of Central America, forming the Middle America Trench. Convergence rates range from 72 to 81 mm/yr, with lower rates towards the north.

The information from a second source should also be considered. Large earthquakes (including an M 8.1 event in 1946) occurred in the Caribbean-North America plate-boundary stretch north of the Dominican Republic and east to Mona Passage (northwestern edge of Puerto Rico) in the twentieth century. However, no historical occurrences from this segment have been recognized (EOS, Transactions, American Geophysical Union, 2010). This is because of the frequency of big earthquakes along this stretch. Such incident was likely higher than the period between Columbus’ arrival and the twentieth century.

The information presented in the book Essentials of Geology is directly related to the articles described above, which means they agree in their theoretical framework. The textbook talks about tectonic processes, although with sufficient detail and quality. The articles, in turn, describe almost the same data as in the textbook but take into account the specifics of the region. As an exciting region to study, the Dominican Republic is a prime example of the processes described in Essentials of Geology.

In the process of working on this paper, I improved my knowledge of geology and tectonics. I studied the specifics of a particular region, namely the Dominican Republic, in the context of geology. Moreover, this work allowed me to consolidate and comprehend the information described in the Essentials of Geology textbook better. On a good example, I understood the main processes of the Earth and the impact on some areas of the planet.

References

EOS, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. (2010). Exploring active tectonics in the Dominican Republic (No. 30). Web.

Marshak, S. (2019a). Earthquakes map [Illustration].

Marshak, S. (2019b). Essentials of Geology (Sixth Edition) (6th ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Marshak, S. (2019c). Overview of Hispaniola’s fault lines [Illustration].

Significant earthquakes on a major fault system in Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the Lesser Antilles, 1500–2010: Implications for seismic hazard. (2018). USGS. Web.