Public administration is a complex entity that exists on the political, legal, and managing levels. It strives to serve the people while executing its functions within the grounds dictated by those levels. Public administration is inherently democratic, and its proper functionality is at the core of democratic processes. However, it does not imply that private management, which stands in opposition to public administration, is anti-democratic. They both exist within one system and perform similar functions, but they differ as far as the factors that can influence them and the way they operate are concerned. This essay will discuss the specifics of public administration and private management in such areas as decision-making, human resources management, and accountability and the implications caused by the differences.

As public administration and private management have to make certain decisions, they consider certain factors, which vary between the two. Private management mostly considers an organization’s gains and losses, as, according to Bodemann (2018), “the highest priority in private sector is producing demanded products in pursuit of profit for shareholders and interests of stakeholders” (p. 43). Meanwhile, public administration should represent the people’s will, meaning that, ideally, the outcome should benefit the people, but it does not always result in that. The people are also not a monolith; there are various groups of people with their needs and problems, which public administration should somehow address. Those groups include citizens, corporate executives, nonprofit groups, and interest groups, all of which want to influence the process of decision-making and the outcome (Raadschelders et al., 2015). Transparency improves decision-making and allows more public participation, which, in a way, removes some of the burdens from public managers and bureaucrats (Jarman et al., 2016). Overall, decision-making for public administration appears to be more difficult and susceptible to various groups that comprise the public, while private management focuses on profit and appealing to shareholders and stakeholders.

As long as humans remain in charge of managing others, there will be the issue of human resources, which both public administration and private managing should be able to tackle. It may seem that public administration would have no problem employing people, as, according to Khan (2017), “Governments are the largest employer in many countries” (p. 34). However, the prestige of working for public administration depends on the country; in the US there is a trend of reducing the size of government officials (Khan, 2017, p. 36). In turn, as public administration loses its appeal and fails to draw personnel, private management becomes a new place to host human resources. The previous point, decision-making, also impacts the trend, as civil servants are not always protected from repercussions of a risky decision and accountability, which will be discussed later (Jarman et al., 2016). As for who might represent a proper public manager, Khan (2017) states that they should act in full knowledge of the global and domestic situation and bear in mind the challenges of globalization. Overall, HRM in public administration faces challenges that should be addressed to regain its prestige.

Accountability accompanies any type of management, but it becomes particularly crucial for public administration, as there is a belief that appointed people have bigger responsibilities. The belief is reflected in the table provided by Bodemann (2018), which compares the public and the private sectors. Although accountability is also essential for the private sector, it could be linked with profitability and whether it was achieved, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1. The Public and Private Sectors.

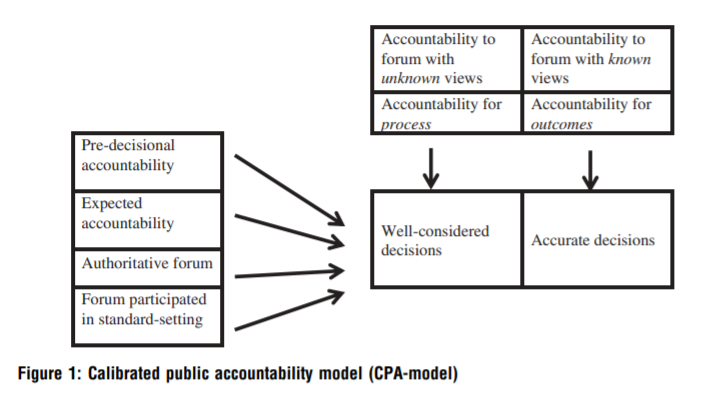

As accountability appears to be a vital component in public administration, there should be ways to ensure that it is applied fairly. Schillemans (2015) proposes a calibrated public accountability model that addresses the absence of specific standards, according to which public executors might be held accountable. The model can be seen in Figure 1, and it is important to note that machine bureaucracies and professional organizations are subject to different standards (Schillemans, 2015). In general, accountability serves as a reminder for managers that their decisions affect people and that they will be held responsible.

In conclusion, public administration and private management might be similar and exist in the same field, but public administration appears to be under more scrutiny when it comes to all the areas considered. A wide variety of groups may influence the process of decision-making; the prestige of public administration is low, as people working there are deemed inefficient; and accountability for public administration is of utmost importance. Meanwhile, the scope of decision-making of private management is smaller; it could gain human resources lost by public administration, and its accountability is directly affected by profitability. Despite public administration appearing less favorable than its private counterpart, it is the nature of public administration to be constantly visible and liable for its actions. In the end, it serves the people and, ideally, works towards the common good, which is not achievable easily.

References

Bodemann, M. (2018). Management in public administration: Developments and challenges in adaption of management practices increasing public value. Springer Gabler.

Jarman, H., Luna-Reyes, L. F., & Zhang, J. (2016). Public value and private organizations. In H. Jarman & L. F. Luna-Reyes (Eds.), Private data and public value: governance, green consumption, and sustainable supply chains (pp. 1-23). Springer.

Khan, H. A. (2017). Globalization and the challenges of public administration: Governance, human resources management, leadership, ethics, e-governance and sustainability in the 21st century. Palgrave Macmillan.

Raadschelders, J., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Kisner, M. (2015). Global dimensions of public administration and governance: A comparative voyage. Jossey-Bass.

Schillemans, T. (2015). Calibrating Public Sector Accountability: Translating experimental findings to public sector accountability. Public Management Review, 18(9), 1400–1420.