Introduction

The purpose of this research project was to investigate public opinion regarding the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits law enforcement searches without an appropriate warrant. This amendment, placed in the Bill of Rights, creates ambiguous implications for personal and national security (Bobber, 1985). On the one hand, it protects privacy interests and prevents searches of citizens unless there is a specific court order to do so. On the other hand, national security and intelligence issues aimed at protecting state interests are more difficult because law enforcement agencies do not have unfettered access to data of heightened interest. As a consequence of this paradox, it was necessary to conduct a public opinion survey not only to determine general trends on the issue but also to look for potentially hidden data between demographic groups in how they were inclined to respond.

Discussion

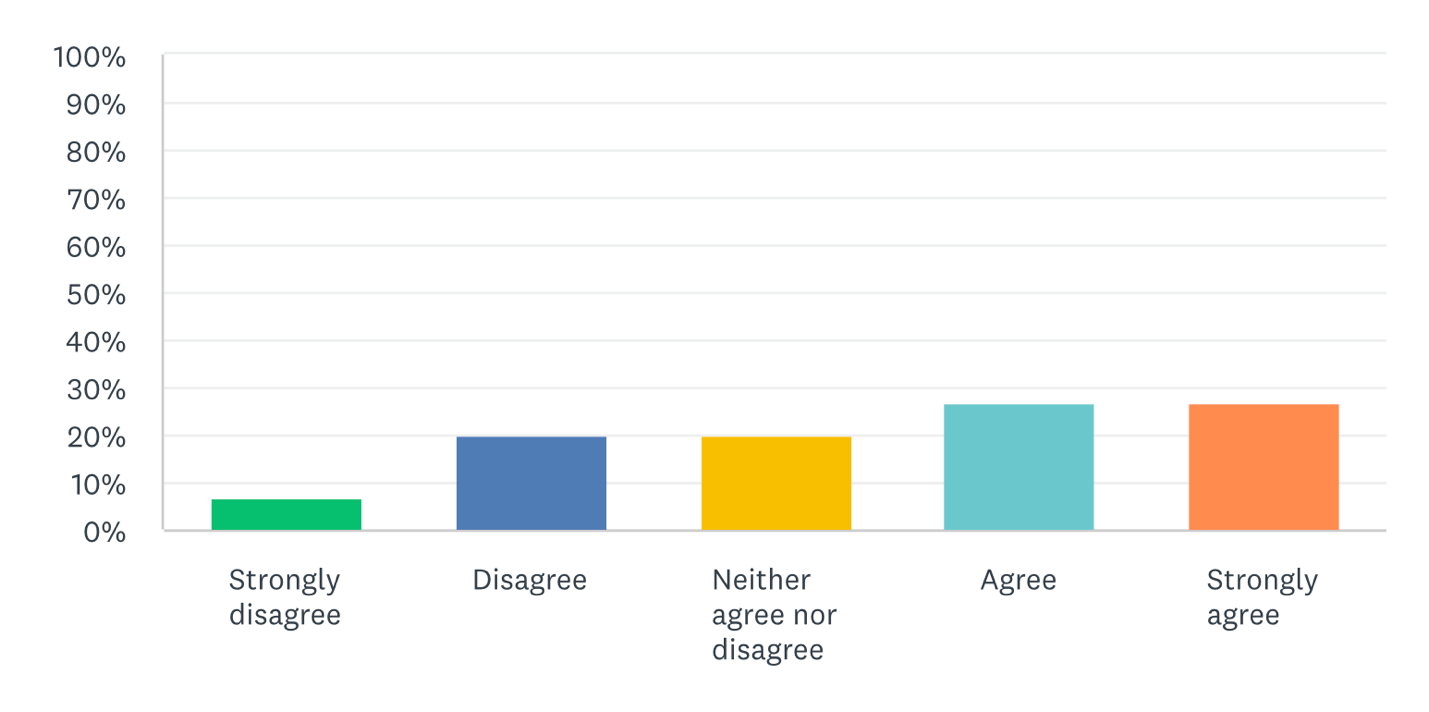

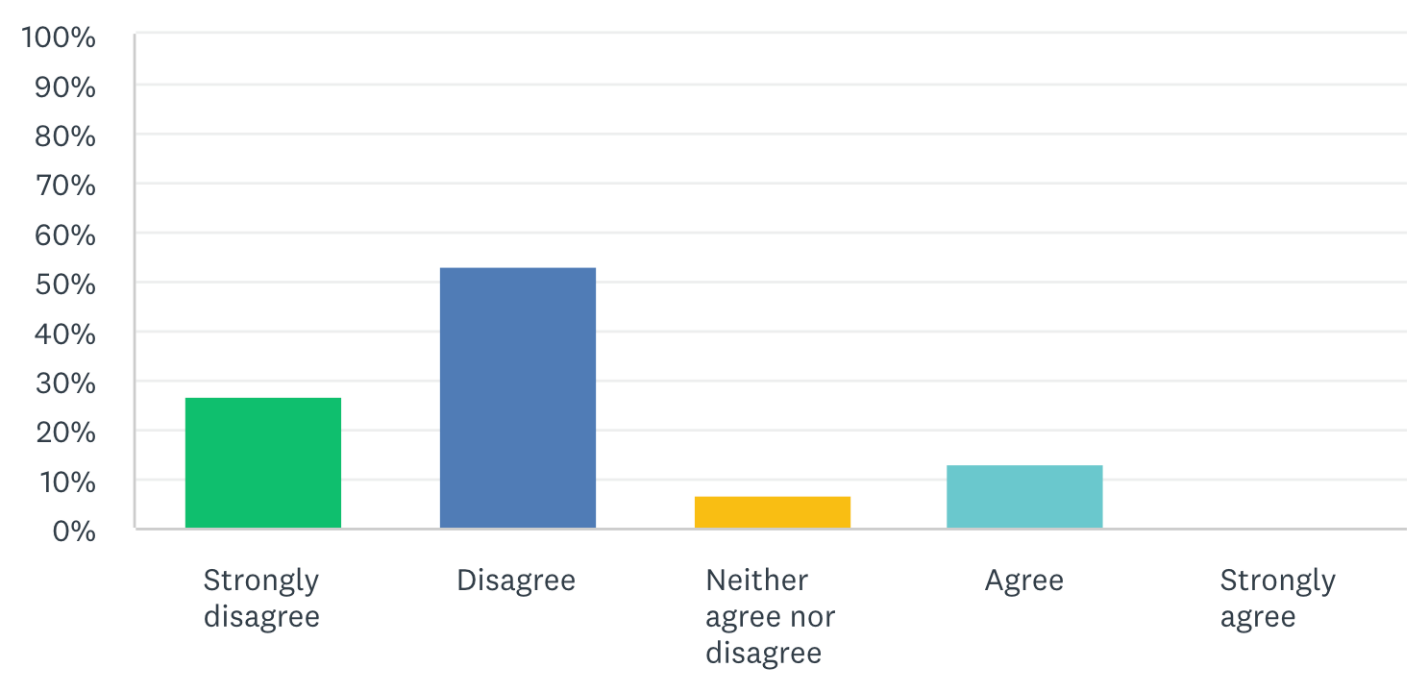

For a sample of respondents (n = 15), represented almost equally by males and females, it was found that everyone was familiar with the Fourth Amendment. More intriguing results were found in the situational scenario questions, which asked respondents to agree or disagree with a statement. In particular, Figure 1 shows that respondents tended to be ambivalent about the need for a search warrant regardless of the situation, although most of them certainly felt that a warrant was necessary. Apparently, the phrase “for any reason” for participants may have been associated with emergencies, in which 86.47% of participants responded that a warrant was not required for searches. This is further supported by the fact that 73.34% of respondents said that a warrant might not be required if a police officer has probable cause to search an individual. On the other hand, the majority of survey participants (80%) called it illegal for law enforcement agencies to wiretap personal phone calls without a warrant. From these results, it can be concluded that in peacetime, most people prefer to protect their own interests, but when critical situations arise, the interests of the state outweigh. However, it can be cautiously assumed that society perceives some tacit contract between it and the state, according to which conducting searches without warrants in critical situations is acceptable, but wiretapping is not. In other words, respondents were willing to acquiesce to government actions contrary to the Fourth Amendment when those actions did not directly affect them.

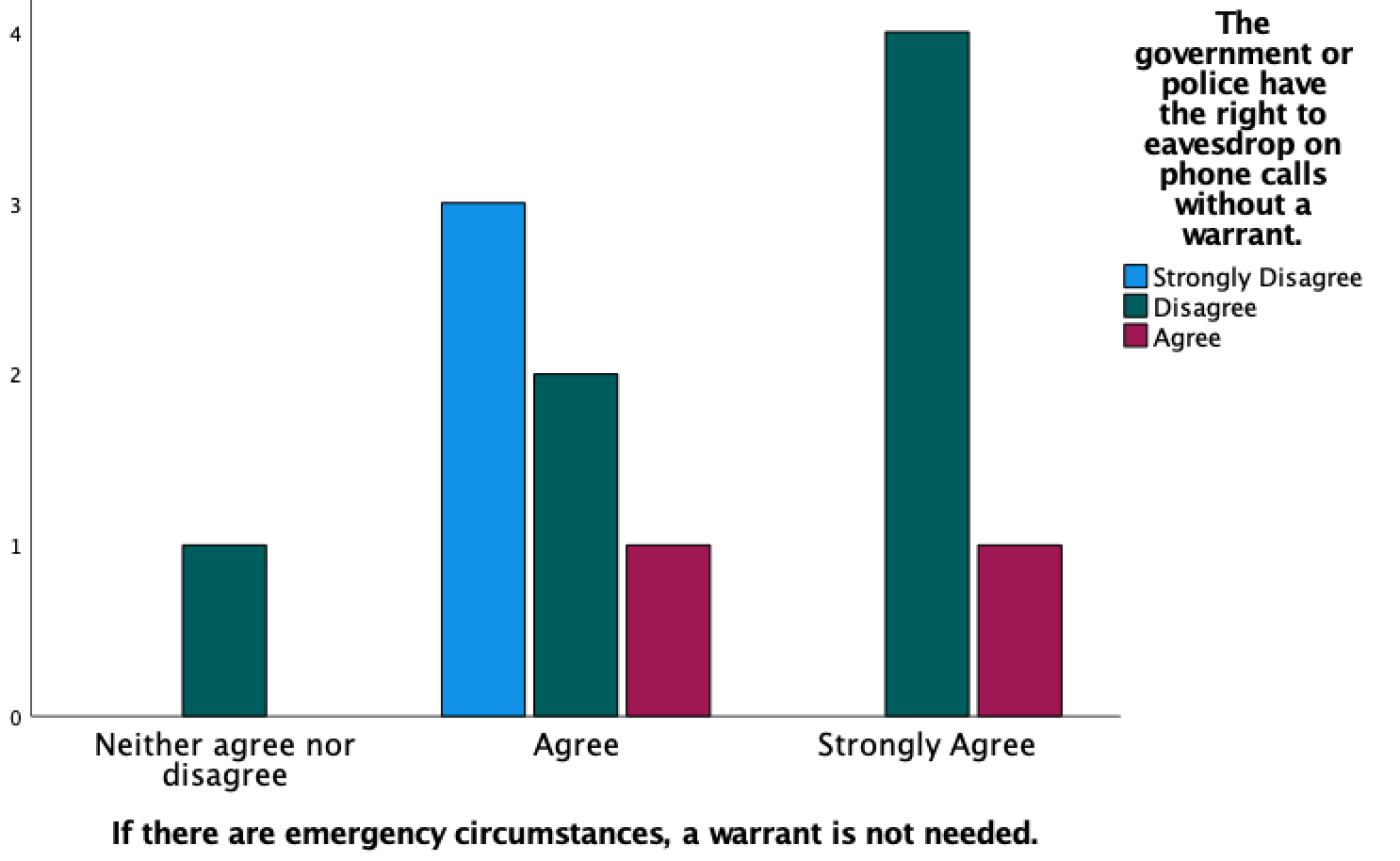

As an additional confirmation of the above assumption, it is worth quoting the results of nonparametric Chi-Square test. This analysis was designed to assess the relationship between respondents’ attitudes toward law enforcement during emergencies and the ability to eavesdrop on phone calls.

Conclusion

The results of this test showed that participants who did not think it was necessary to have a warrant during emergencies mostly disagreed with the possibility of phone tapping by the authorities. The result was statistically significant, which means there is a possibility of extrapolating the results to the population. This creates a paradoxical picture in which virtually the same violation of constitutional law is differentially perceived by people depending on how that violation affects their lives.

Reference

Bobber, B. J. (1985). Fourth amendment. Warrantless search of packages seized from an automobile. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-), 76(4), 933-954. Web.