The matters of race are still of considerable importance in today’s world. While the age of colonialism is over, the increasingly globalizing post-colonial world introduces new racial and ethnic hierarchies on both domestic and worldwide scale. Contemporary art reacts to these developments and mirrors them in the works of such artists as David Hammons, Roberts Colescott, William Pope L., Penny Siopis, and Julie Mehretu. In general, the artists of the late 20th focused on domestic racialized hierarchies, but the 21st century brought a global outlook of racial and ethics problems and the attempts to see past race.

David Hammons was one of the artists who interpreted race in the second half of the 1980s. He already made a name for himself during the previous decades through his works during the Civil Rights era, as well as his puzzling Bliz-aard Ball Sale in 1983, when the artist sold snowballs. However, within the time frame of this paper, Higher Goals, created in 1986, is or greater interest. Entirely in line with Hammons’ “deliberate strategy to make ‘unsaleable’ works,” Higher Goals was a temporary sculpture constructed of telephone poles 20 to 30 feet high with basketball hoops on their tops. Each of the poles is studded with bottle caps arranged in careful geometrical patterns.

The artwork interpreted and questioned the place of African Americans in the post-Civil Rights era with particular attention to the social lifts available to black youth. Although its composition did not point specifically to the matters of race, the use of basketball imagery still hinted to basketball as a predominantly black sport. Apart from that, Hammons always maintained that he, as a black artist, had a moral duty “to graphically document” what he felt socially. In this sense, Higher Goals was a comment on the arduous path to success for a black person in America. Professional sports were and are among the limited number of social lifts available for an African American, but achieving success in this highly competitive field is no easier than climbing a 30-feet pole. For every athlete who is able to reach the top, there are thousands of those who do not – just as numerous as the bottle caps studded into the poles. Finally, one should not disregard the deliberately unsaleable nature of the piece. By intentionally making his artistic reflection on black athletes unavailable for purchase, Hammons criticized the commercialization of African American bodies in professional sports.

Another artist to analyze this theme in his works was William Pope L., famous for his practice of performative crawl interventions. One of his works related directly to the matters of race and, in particular, commercialization of black sports bodies was the Budapest Crawl of 1999. In this performance, Pope, dressed in white athletic shorts, a sports jersey, Nike sneakers, and elbow and kneepads, crawled from the Danube River to the building of the Hungarian Parliament in Budapest. While traversing the capital of Hungary, Pope held a bottle of cologne in one hand and a small globe in another. As a performance artist, Pope used his Budapest Crawl to attract attention to the increasing international commodification of a black body.

The design of the performance attracted attention to racial matters, beginning with a sharp contrast between the artist’s black skin and his white clothes. The sports uniform was also a pivotal element in making the performance a sharp social commentary. Throughout the 1990s, black athletes and, in particular, basketball superstars became a central feature in sports advertising for the company Nike, thus enacting “a discursive relation between race, advertising, and brand recognition.” Moreover, advertising often represented black athletes as examples of racialized sexual desire, thus reducing them to consumable objects. In this historical context, Pope’s Budapest Crawl was a protest against the commodification of the black body as a sexualized consumable, symbolized by cologne as associated with male sexual appeal. The artist’s mode of moving was an apt choice to highlight the point. Nike’s basketball commercials of the 1990s focused on Michael Jordan’s ability to “fly” – even his logo depicted the athlete as “reaching upward and defying gravity.” Pope’s lowly crawl, on the other hand, served as a counterpoint, suggesting that, no matter how high a black male athlete can fly, mass culture still regards him as a commodity.

By addressing this theme, Pope sent a more consistent and coherent message on the commercialization of black athletes and their bodies in the late 20th century than Hammons did in 1986. Hammons’ focus was entirely domestic, but Pope’s decision to set his performance in Europe was an attempt to address the issue on the global level, corresponding to the worldwide character of sports advertising. Still, even while the means of addressing the issue became international, the core problem at the heart of the artwork remained American. Pope criticized commodification of black bodies in sports advertising and inquired whether it translated into “a better way of life for black athletes and black America in general.” Thus, while he broadened the scope of addressing racial issues as compared to Hammons, the issues themselves remained the same domestic American problems. This contradiction may be one of the reasons why the European audience in Budapest did not pay much attention to Pope’s performance in 1999. Despite the globe in the artist’s hand, the performance was not global in theme – only in its scope.

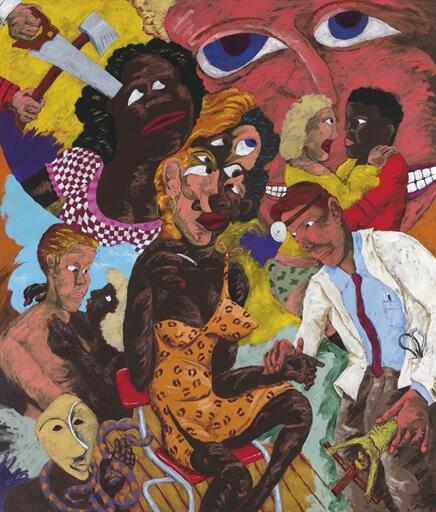

Yet another notable artist who addressed topics of race and ethnicity during the 1990s was Robert Colescott. In his Grandma and the Frenchman: Identity Crises painted in 1991, Colescott depicted a woman with a multitude of hairs, noses, and ears of many races as well as their skin colors. According to the artist’s explanation, the piece is “all about identity – this woman cannot just have a two-faced Picasso head, she must be even more fragmented” to reflect her immensely complex identity. The image of the grotesquely misshapen head emphasizes the impossibility of representing this identity in strictly racial terms for the people of mixed ancestry. In essence, Identity Crises uses an absurd image to highlight the absurdity of racialized divisions. If the people around are of mixed heritage – and have been so for generations – hierarchies of power based on race become entirely senseless.

Yet senseless as they are, such hierarchies and labels persist, as demonstrated by Colescott’s later painting dubbed Lightning Lipstick. This piece depicts a light-skinned woman looking at her dark-skinned reflection in the mirror and exclaiming in Spanish: “Soy Latina!” (“I am a Latina!”). The dark reflection, however, disagrees with the woman’s self-assessment and designates her as “Negrita” (“Black woman”). Lightning Lipstick interprets the identity conflict faced by the darker-skinned Hispanics and defined by the interpolation of ethnic and racial categories in American society. While they identify as Latinos, thus basing their identity on their ethnic and cultural background, others, especially the white North Americans, see them as “blacks” because of their color. Just as Identity Crises, this painting aims to emphasize the immensely complex racial and ethnic history of America and its population. The images of a female black slave and a man in stereotypically Spanish clothes underline this message, much like the facial features do in Identity Crises. Colescott denies racialized hierarchies just as empathically as Hammons or Pope, but, instead of limiting himself to the black-and-white dichotomy, broadens his scope by tying to embrace American diversity in its entirety.

If the artists of the 20th century preferred to address matters of race and ethnicity in a domestic context, those of the new millennium offered a more global outlook, as demonstrated by South African Penny Siopis. In her Overboard, Siopis depicts a black person half-submerged into a bloodlike red liquid. Siopis’ paintings are notable for being “personal and political at the same time,” and, in this case, the political subtext appears to be racial. The force that drags the black body down is likely the same force that has thrown it “overboard,” out of social context. Siopis suggests that, even in the post-colonial world, new racial hierarchies emerge and assert themselves. Yet, unlike Pope’s or Hammons’ works, the painting contains no references to specific domestic issues. Instead, it examines the black body and blackness per se – on a global rather than national scale.

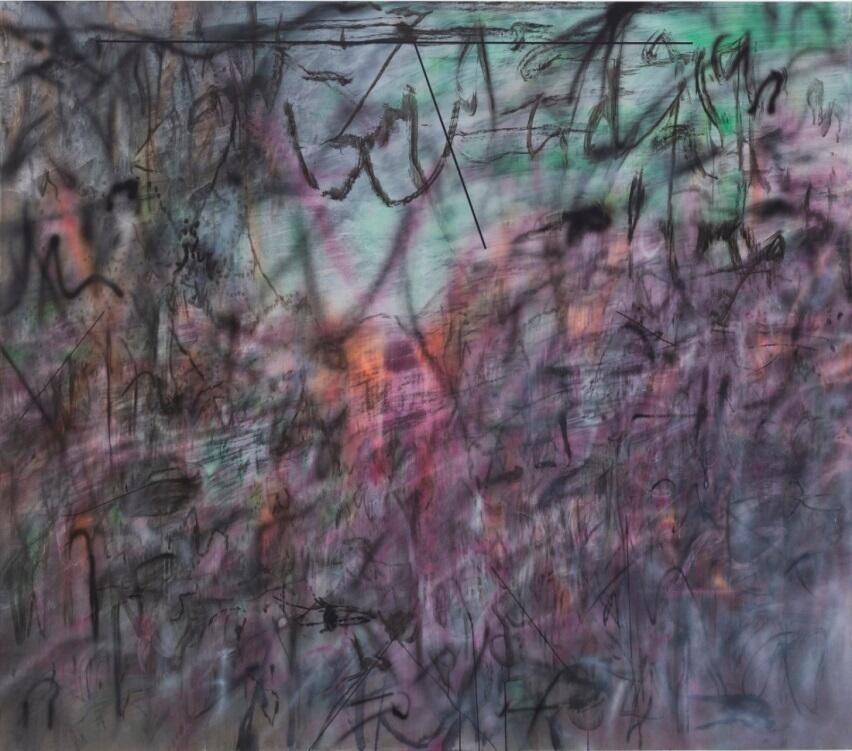

Another example of the same tendency is Ethiopian-born Julie Mehretu. Unlike her predecessors, Mehretu addresses racial and ethnic issues on the worldwide scale, paying attention to the Black Lives Matter or the Middle East refugee crisis simultaneously. Her Mural created in 2009 is a vibrant abstractionist representation of the intricacies of the contemporary globalized world. Figures of all sizes, shapes, and colors reflect the chaos of the rapidly decolonizing world and the new racial and ethnic interactions that emerge after the fall of colonialism. The scale of the work makes it impossible to embrace in a single look: one has to either examine the painting piece-by-piece or risk being overwhelmed by its sheer chaotic magnitude. Instead of sending a message on a single racial or ethnic theme in a national context, Mural encourages a “deep, lengthy contemplation” of the globalized world with its racial and ethnics tensions. Thus, Mehretu demonstrates a genuinely global approach to the matters of race and ethnicity.

Another characteristic feature of Mehretu’s work is an attempt to see past color. In stark contrast with Mural, her Conjured Parts (eye): Ferguson, painted in 2016, uses color sparingly and as a background, putting the grey figures at the forefront of the piece. Mehretu admits that, for her, color “has always had a sort of social role, a descriptive role.” Hence, the reluctance to use color in the painting devoted to one of the most racially significant events of the last years may signify the artist’s desire to see past these descriptive social roles. In this sense, one may interpret Ferguson as an attempt to overcome social labels assigned to the color and, by extension, race and ethnicity and envisage post-racial art.

To summarize, the interpretation of race and ethnicity in contemporary art from 1985 to the present went from covering domestic problems in a domestic context to globalized outlooks and attempts to see past race. Hammons’ Higher Goals criticized limited social lifts for African Americans as well as the commodification of black bodies. Pope’s Budapest Crawl addressed the same domestic problem on an international scale. Colescott’s paintings highlighted both absurdity and resilience of ethic and racialized hierarchies among the people of mixed heritage. Finally, Siopis’ and Mehretu’s pieces look at race and ethnicity globally and emphasize their overwhelming complexity in a contemporary world, while Mehretu also attempts to move past color, race, and ethnicity as relevant categories.

Bibliography

Angelis, Alessandra De. “An Artist’s Dance through Medium and Vision.” In Penny Siopis: Time and Again, edited by Gerrit Olivier, 277-283. Johannesburg: Wits UP, 2014.

Barber, Tiffany E. “William Pole L.’s Budapest Crawl and Black Male Sports Bodies in Advertising in the 1990s.” In Out of Bounds: Racism and the Black Athlete, edited by Lori Latrice Martin, 321-254. Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, 2014.

Dufur, Mikaela. “Race Logic and “Being Like Mike:’ Representation of Athletes in Advertising, 1985-1994” In African Americans in Sport, edited by Gary A. Sailes, 67-84. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Filipovic, Elena. David Hammons: Bliz-aard Ball Sale. London: Afterall Books, 2017.

Gleeson, David. “David Hammons: Give Me a Moment.” Art Monthly 399 (2016): 24.

Harney, Elizabeth. “Reimagining Global Modernity in the Age of Neo-Liberal Patronage: The History Paintings of Julie Mehretu.” In What Was History Painting and What Is It Now?, edited by Mark Salber Phillips and Jordan Bear, 234-253. Montreal, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2019.

Pinder, Kimberly N. “Biraciality and Nationhood in Contemporary American Art.” In Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History, 391-401. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Woubshet, Dagmawi. “An Interview with Julie Mehretu.” Callaloo 37, no. 4 (2014): 782-798.

Illustrations