Introduction

In the digital economy of the new age, there is a noticeable trend toward the use of cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrencies should be understood as virtual alternatives to currencies distributed using blockchain technology; one of the most popular and early cryptocurrencies is Bitcoin. Bitcoin has unique characteristics that give the currency its viability, namely the limited resource, the difficulty of obtaining it, the reward system, and the ability to exchange it. In many countries, Bitcoin can be used to pay for goods and services, making cryptocurrency an excellent substitute for government money, the circulation of which is controlled. The economic freedom to use Bitcoin, due to the blockchain’s cryptographic features, creates a wide range of uses for Bitcoin. Meanwhile, many of the practical uses of cryptocurrency are imperfect and raise ethical dilemmas. This paper will provide a substantive analysis of recommendations for improving Bitcoin’s capabilities.

Thesis

The widespread use of Bitcoin presents economic freedoms for users, but it also creates ethical issues related to socio-economic inequalities and environmental concerns, so recommendations for strategies to improve Bitcoin cryptocurrency practices are appropriate.

Ethical Dilemmas

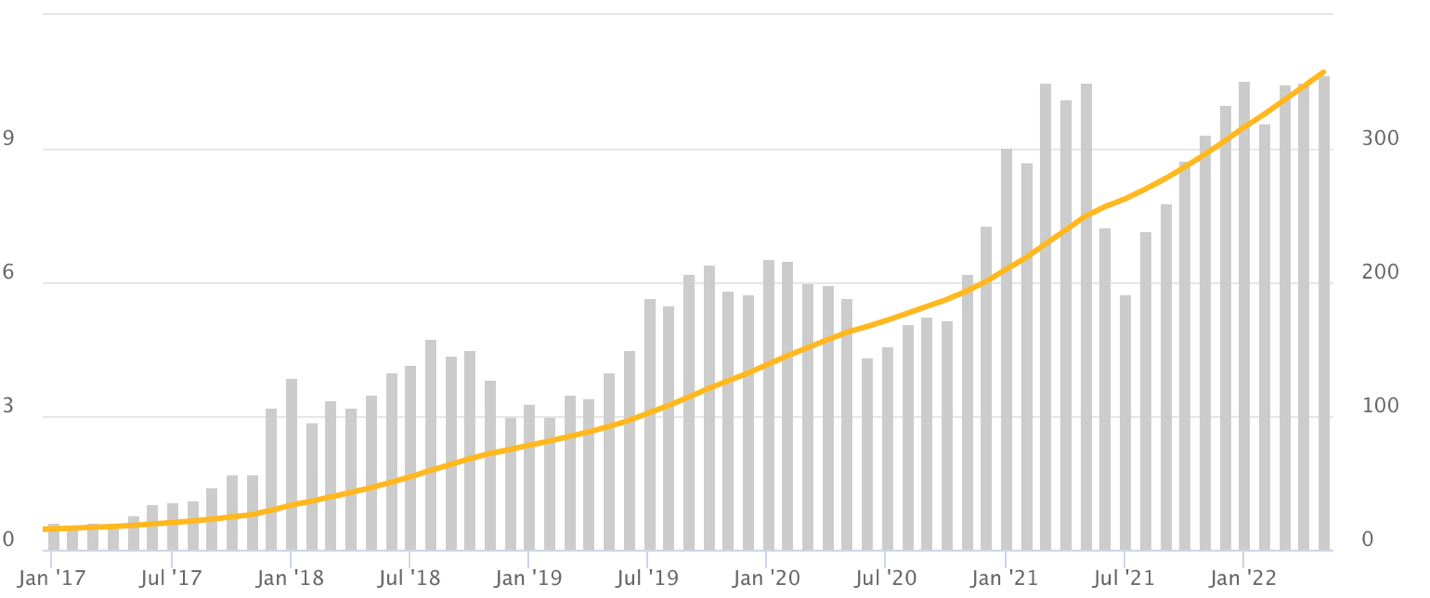

Although Bitcoin has created excellent potential for an alternative digital economy and has effectively formed a conduit for uncontrolled financial exchange, its use leads to a number of serious ethical issues and threats to the well-being of vulnerable groups. In particular, the use of Bitcoin, especially in recent years, has set a precedent for widening the gap between the rich and the poor. If one turns to the dynamics of Bitcoin’s rate to the USD (Figure 1), it can be clearly seen that in eight years, the value of Bitcoin has been maximized by more than 17,800 times. While high volatility is not a problem in and of itself, the cryptocurrency’s gradual rise in price has inhibited opportunities for a wide range of individuals from poorer regions to buy Bitcoin. In turn, this contradicts the ethical ideas of Fichte, who argues that currency should be used freely for commodity exchange — the uncertainty in the price of cryptocurrency creates a problem for such exchange (Kosch, 2018). Currently, only wealthy users can buy Bitcoin, and high fluctuation activity could widen this gap.

In addition, there is a growing divide on the basis of users’ religious views. More specifically, Bitcoin is not an acceptable currency in most Shariah states because the current haram prohibits the use of intangible, digital currencies associated with high investment risks (Lateh & Rejab, 2021). Such countries include Iran, Algeria, Turkey, and Egypt (Orji, 2022). Despite the fact that some Islamic governments are creating halal alternatives, Bitcoin, as the leading cryptocurrency, turns out to be forbidden to Muslims. This creates a problem for joining the practice of cryptocurrency investing, and as a result, Muslims are losing their potential for economic freedom due to the haram nature.

The use of Bitcoin also proves problematic from the perspective of Kantian ethics. In particular, Kant postulated that motives determine the moral value of action while calling virtue a universal good (Hill & Cureton, 2018). From this perspective, Bitcoin presents ample opportunities for criminal activity because its circulation is decentralized and uncontrolled. Users utilize Bitcoin to pay for drugs, contract murders, and other illegal purchases on the darknet (Bahamazava & Nanda, 2022). Statistics show that Bitcoin’s illegal turnover is breaking records, reaching $14 billion by 2021 (SunFollow & Smagalla, 2020). Accordingly, the very existence of Bitcoin creates a vulnerability in universal ethics by providing opportunities for the criminal industry to develop.

Finally, a serious ethical dilemma regarding cryptocurrency is the damage done to the planet’s environmental security. Bitcoin’s technical nature allows users to mine it by multiplying the computing power. According to official data, Bitcoin mining exceeds 124.71 TWh, which severely strains the power grid, a figure that tends to grow, as shown in Figure 2 (CCAF, 2022). The energy-intensive mining process increases the production of carbon dioxide, a predictor of global warming worldwide (Di Febo et al., 2021). The consequences of this intensification are the death of ecosystems, reduced biodiversity, and a rapid increase in global ocean levels.

Recommendations

Solving the dilemmas described above is an applied task for improving cryptocurrency usage practices. First, developing a recommendation to reduce the socio-economic gap when using Bitcoin is necessary. This can be accomplished by providing quotas for people from low-income countries to buy Satoshi and by introducing progressive tax obligations for those with large Bitcoin holdings. If cryptocurrency is conceived as an alternative currency, extrapolating actual monetary policy to it seems appropriate. In this case, both all Bitcoin users confronted with the new regulations of digital currency ownership and those who want to buy the currency but do not have such financial capabilities are stakeholders. In addition, the person responsible for imposing restrictions will be national governments and exchanges, which will withhold transaction tax.

In terms of infringement of the rights of Muslim citizens, it is necessary to develop strategies to revise the haram policy to allow cryptocurrency use in Shariah countries. Otherwise, it is possible to develop alternative tokens that would have identical economic potential but would be halal. In this case, national central banks should develop acceptable ownership and investment strategies that introduce Muslims to cryptocurrencies and do not contradict cultural taboos. Stakeholders include Muslim users who want to use cryptocurrencies legally, national governments, and other cryptocurrency users who will experience increased demand for tokens.

To address the criminal side of Bitcoin, increased law enforcement measures to control the sale of illegal goods and services, combined with increased scrutiny of cryptocurrency users, have been proposed. One measure could be to ban the use of Bitcoin on the darknet and to impose a ban on the activity of cryptocurrency wallets that have been found to be implementing illegal activity. This would require a review of blockchain practices, as by now, all cryptocurrencies are anonymous; perhaps the introduction of an owner identification registry is a reasonable recommendation to inhibit criminal activity by users. In this case, all cryptocurrency users are stakeholders, especially those who have made illegal purchases on the darknet. In addition, the recommendation would require increased national control of law enforcement and an increased budget allocation.

A final recommendation is to limit the ability to purchase high-powered computing equipment and invest in developing less environmentally harmful computers. Such a strategy would reduce the carbon footprint of mining, but it would take time to rethink mining practices. Cash to invest in technology and the development of carbon capture and recycling technologies are also additional resources. Stakeholders include national governments, extensive technology manufacturing companies, and cryptocurrency miners who will have to face new mining practices.

Conclusion

To summarize, despite its many benefits, Bitcoin poses severe ethical threats. This relates to socio-economic and religious discrimination, increased criminal activity, and environmental damage. Recommendations to minimize each of the problems have been proposed in the paper, but such recommendations provide ample opportunity for discussion. In particular, an important issue continues to be determining the need to restrict the use of cryptocurrencies and the relationship of such bans to Bitcoin’s initial philosophy.

References

Bahamazava, K., & Nanda, R. (2022). The shift of DarkNet illegal drug trade preferences in cryptocurrency: The question of traceability and deterrence. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 40, 1-18. Web.

CCAF. (2022). Bitcoin network power demand. Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance. Web.

Di Febo, E., Ortolano, A., Foglia, M., Leone, M., & Angelini, E. (2021). From Bitcoin to carbon allowances: An asymmetric extreme risk spillover. Journal of Environmental Management, 298, 1-8. Web.

Hill, J., & Cureton, A. (2018). Kant on virtue: Seeking the ideal in human conditions. In N. Snow (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of virtue (pp. 263-280). Oxford University Press.

Kosch, M. (2018). Fichte’s ethics. Oxford University Press.

Lateh, N., & Rejab, S. N. M. (2021). Sharia issues about Bitcoin cryptocurrency transactions. In N.

N. M. Shariff, N. Lateh, N. F. Zarmani, & Z. S. Hamidi (Eds.) Enhancing halal sustainability (pp. 119-128). Springer.

Orji, C. (2022). Bitcoin ban: These are the countries where crypto is restricted or illegal. EuroNews. Web.

SunFollow, M., & Smagalla, D. (2020). Cryptocurrency-based crime hit a record $14 billion in 2021. The WSJ. Web.

Yahoo! (2022). Bitcoin USD (BTC-USD). Yahoo! Finance. Web.