Executive Summary

Oman Oil Refineries and Petroleum Industries Company (ORPIC) is one of the strategic governmental interests, responsible for the excavation and production of numerous gas and oil-related materials. The production values of ORPIC are estimated at 943,000 barrels a day in gas and 31.4 million tons of oil equivalent per year in gas (ORPIC 2019). At the same time, the company’s excavation and rig maintenance division suffers from increased rates of accidents per 1,000 workers per year.

In order to improve the situation and achieve the goals of a 10% reduction in accident rate by the end of 2019, significant changes are required. Immediate solutions suggest an introduction to change management and the development of a safety culture among the workers. Long-term solutions include a paradigm shift from quantity to quality, significant upgrades to facilities and equipment, as well as investments to employee recruitment and retention.

Introduction

Oil and gas industry constitutes one of the major elements of Oman’s exports. Despite the country’s effort to diversify its economy, the use and production of natural resources remain one of its primary revenue streams, with daily production rated at 943,000 barrels a day and gas production at 31.4 million tons of oil equivalent per year (MtoE) (ORPIC 2019). While the country remains a relatively small exporter of gas when compared to other countries, with 70% of its excavated resources used to satisfy the domestic demand, the Omani oil sector is able to compete with the rest of the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (ORPIC 2019).

Oman Oil Refineries and Petroleum Industries Company is one of Oman’s largest natural resource extraction companies. It possesses a full production cycle of operations ranging from oil and gas rigs to refineries as well as aromatics and polypropylene facilities located near Sohar and Muscat (Challenges facing ORPIC growth 2019). It allows ORPIC to provide a multitude of products, such as fuel and plastics, satisfying demand in Oman and other countries. The company was created as a result of a merge of large government-owned properties in 2011.

As it stands, it employs over 3000 employees and works with more than 500 private contractors. Some of the noteworthy properties owned by ORPIC include refineries in Muscat, Suhar, Jifnain, Raysut, as well as the new plastic plant in Liwa along with a gas reservoir in Farhoud (ORPIC 2019). The company’s total refining capacity is estimated at 198,000 barrels per day. ORPIC is considered to be one of the fastest-growing businesses in the Middle East. One of the primary humanitarian concerns of the company lies in reducing its accident rates. According to the 2019 report, the number of non-lethal accidents in ORPIC was 27 per 1,000 employees, with the goal for 2019 to reduce that number by 10% (ORPIC 2019). The majority of work-related incidents happen in the high-risk area of operations, such as excavation and maintenance.

Problem Statement

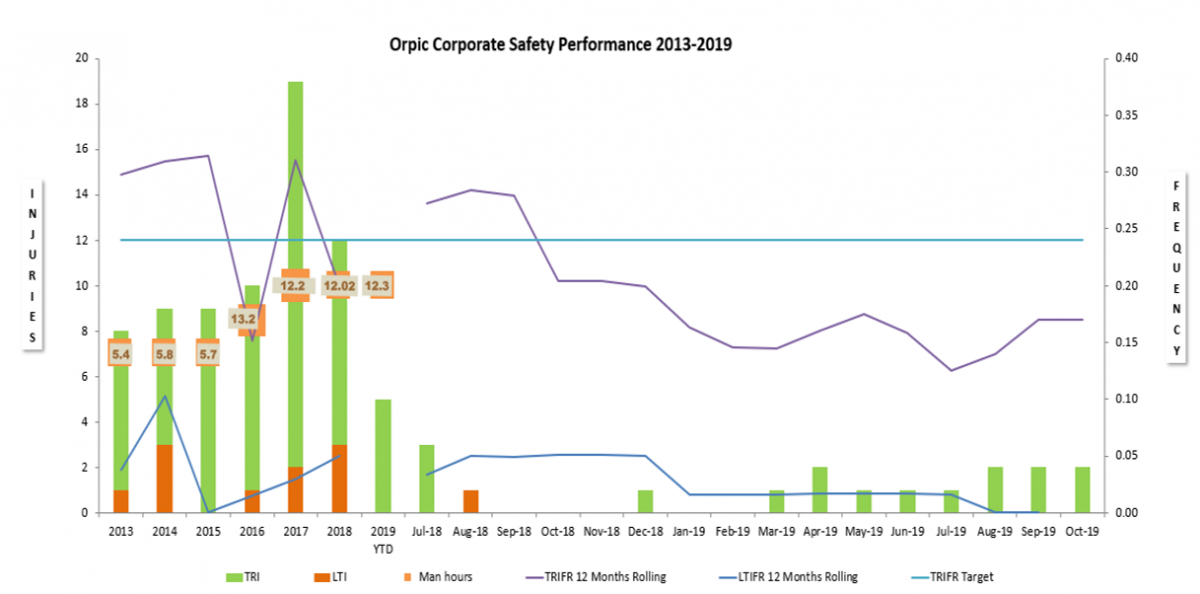

Accidents in the workplace are a significant threat to ORPIC, as they cause injuries and potential loss of human life, financial expenditures and a loss of reputation. As seen from Graph 1, the frequency of injuries in the workplace have been on the low for the last year. If one compares the data available for the years 2013-2017 and the current metrics, it is safe to say that the rate plummeted dramatically.

Yet, the more detailed results for the current year show some instability and fluctuation. At present, the non-fatal accident rate is 27 per 1,000 workers, which is a significant number. Although it is impossible to rule out the probability of accident due to the human factors, the company must make an effort to minimise the potential for harm and death among its workers. The main goal regarding safety management now is to reduce the accident rate by at least 10% by the end of the year.

The motivation for this paper is the vast impact that work accidents have on the key business aspects. Firstly, handling accidents is costly; high-risk environment and poor safety management may lead to an otherwise unnecessary financial burden. Accidents are problematic in terms of time management: ideally, each accident needs to be investigated thoroughly to locate the root causes. There is the reputation aspect to the issue of increased accident rates: unfortunate incidents undermine ORPIC’s standing on the market and might break customers’ trust. Lastly, the problem of accidents in the workplace can be approached from the moral standpoint.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper stems from the complexity of the issue and its impact on the functioning of ORPIC. The present research seeks to analyse factors affecting safety issues in the ORPIC’s excavation and oil rig maintenance department and provide a potential solution to achieve the goals for 2019.

Research Design

The present research is an analysis of the existing, up-to-date data provided by ORPIC itself. The data used describes the most recent accidents with as much information as publicly available. This paper employs three theoretical frameworks for the evaluation of the main causes of accidents in the ORPIC’s excavation and oil rig maintenance department. These are Root Cause Analysis (RCA), Fishbone analysis framework, and McKinsey’s 7S model with the latter demonstrating potential issues in the organisational structure of the department. In the information dissemination section, it is possible to find the connections between different factors as well as detailed explanations of the accident-related processes.

Analysis

The tools selected to be used in the analysis and evaluation of the situation in ORPIC’s are Fishbone and McKinsey’s 7S method. Fishbone is an analytical tool typically utilised as a part of the Sigma Six evaluation. It helps visualise the causes and effects of various problems in order to identify its root causes (Desai, Desai & Ojode 2015). The diagram consists of the Head section, which illustrates the major problem (in this case, accidents in the excavation and oil rig maintenance department), whereas the bones of the diagram would illustrate major causes of incidents. Additional factors would be added to each bone in order to represent the symptoms of the larger problem. The instrument was chosen for its versatility and effectiveness in keeping the attention on systematic solutions rather than temporary measures.

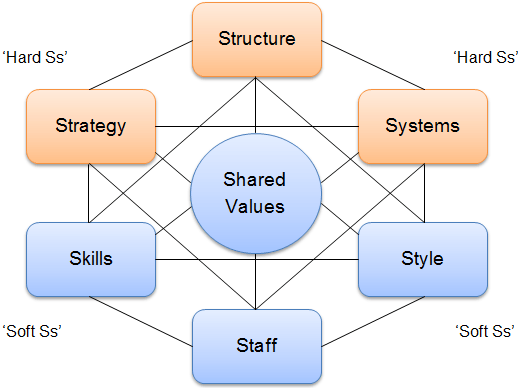

McKinsey’s 7S model is another tool to be used in the evaluation and analysis of safety issues in the ORPIC’s excavation and oil rig maintenance department. It is an organisational analysis tool that could help evaluate the existing systems and the internal situation within an organisation (Stowell & Welch 2012). The purpose of 7S is to analyse all of the aspects of organisational performance, which include strategy, skills, style, systems, shared values, staff and structure, in order to understand how well these elements work on their own and in conjunction with one another. The knowledge provided by McKinsey’s model would be invaluable in the development of potential solutions to the problem of safety and accident prevention.

Organisation Structure, Life Values, and Root Cause Analysis

Root cause analysis is an excellent tool for pinpointing the deeper, hidden causes of undesired events. However, as much as this method presents a great number of advantages, it may be challenging to apply because it requires utmost honesty from people in the decision-making positions. On their official website, Orpic states four pillars on which it bases its identity in the business world:

- putting health, safety, and environment first;

- maximising the potential of each employee;

- capitalising on fidelity, integrity, and engagement; and

- serving Oman and the customer.

While this corporate philosophy makes sense at first glance, deeper analysis shows the lack of congruence between words and actions. Safety performance at Orpic is still at suboptimal level, and the company has yet to live up to the claims it is making for the public.

Root cause analysis allows to trace back accident causes, and one of the ways of doing it is asking “why” repeatedly until the true reasons reveal themselves. Below is the breakdown of a specific problems within the root cause analysis framework:

(0) Problem: the accident rate at Orpic is currently at 27 incidents per 1,000, which is far from satisfactory;

- Why? Because safety is apparently assigned low priority as compared to other values within the corporation;

- Why? Because of the flawed resolution of conflicting goals and the conflict between downstream vs. upstream efforts;

- Why? Because of ineffective organisational structure;

- Why? Because Orpic has an inefficient organisational structure in which one observes diffusion of responsibility and authority. At the same time, personnel suffers from their low-level status and lack of independence;

- Why? Because the organisation is characterised by a low level of connectivity between departments; between managers and their subordinates. Limited communication channels result in poor information flow, which impedes the improvement of safety management.

(0) Problem: the accident rate at Orpic is currently at 27 incidents per 1,000, which is far from satisfactory;

- Why? Because of ineffective Technical Activities;

- Why? Because Orpic seems to be failing to eliminate basic design flaws;

- Why? Because the company only makes superficial safety efforts;

- Why? Because it bases safeguards on false assumptions;

- Why? Because it is challenging for Orpic to exert effective risk control due to the complexity of the issue.

As seen from these two RCA breakdowns, there is more than one explanation to the same problem. Also it becomes apparent that in order to resolve the increased accident rate issue, the mobilisation of many different aspects is needed. The following sections address the problem in more detail and offer their conceptualisation of cause analysis.

Fishbone Analysis

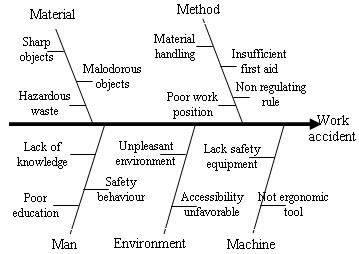

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the major causes of accidents in ORPIC include personal employee mistakes, organisational inadequacy, inadequate work standards and force majeure events. Below is the breakdown of root causes of accidents in alignment with the Fishbone method:

Man

Statistically, most accidents in the department occur due to personal mistakes of the employees while on the job (ORPIC 2015). An employee might suffer from a lack of attention due to tiredness, extensive periods of labour, weather conditions or negligence, resulting in an accident. These types of accidents are almost always caused by human factors. These usually result in minor injuries and damage of the product or equipment.

Environment

Force majeure events typically result in the largest number of grievous injuries and deaths. These occur due to a combination of various factors inside and outside of the company’s control. Large-scale fires, floods, explosions and other events that have the potential to lead to the mass loss of life are classified as force majeure events. The last known accident in ORPIC occurred in 2007, an explosion of stored fuel and chemicals causing the deaths of 28 employees (ORPIC 2015).

Method

Inadequate working standards are typically connected to large force-majeure events and smaller-scale accidents. Typically, they occur as a result of equipment mishandling, poor or inadequate standards of labour quality and safety, managerial negligence and outdated equipment. The latter is the most prominent issue for ORPIC. Aside from their new facility in Liwa, most of their refineries are over 20 years old (Kalyanam 2018).

Although they receive upgrades, the overall exhaustion of major system components and the outdated technology poses an increasingly significant threat to the employees. Lastly, there is organisational inadequacy, the effects of which are harder to estimate. Oil and gas industry require its employees to be supremely qualified and physically resistant to work in excavation and oil rig maintenance (Berkowitz, Bucheli, & Dumez 2017).

Due to these requirements, it is often hard to fill out vacancies, which results in increased workloads for the remaining staff. Alternatively, vacancies are filled with subpar candidates, which increases the probability of accidents. Additional issues arise from inadequate or outdated training methods. Hard-pressed to provide stable outputs, ORPIC seldom results to training employees on the job, which increases the probability of work-related injuries (ORPIC 2015).

Lastly, there are communication issues between line managers and middle-class managers responsible for operational safety. Typically, line managers discover potential issues with work safety first. However, instead of taking immediate decisions on the ground, they are required to relay the information to middle-managers, who then make the appropriate decisions and outline courses of action. As a result, valuable time is lost, during which the potential danger might escalate.

Material

The most relevant “material” type of threat in the context of oil and gas industry is hazardous waste. Hazardous waste is defined as discarded materials with properties that might turn them into a public health threat if not managed properly. Many oil and gas companies find themselves trapped in the so-called hazardous waste loop where their attempts at managing it in sustainable ways fail every year. Orpic has already been making efforts to address the issue of hazardous waste; however, the projects have only been limited to shorter periods of time and “pilot” in nature.

One example of such a project is a two-year pact that Orpic entered in 2017 together with Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) and the Japan Cooperation Centre Petroleum (JCCP) (Orpic in pact to treat hazardous refinery waste 2017). Orpic stated that if successful, the new hazardous waste management initiatives will open up new frontiers, not only for the company but also for the entire country. As one may imagine, realising the initiative will require making changes to other aspects outlined in the Fishbone diagram as well. Successful material management is likely to rely on man (training and education) and method (organisation structure), which indicates the complexity of the issue.

Machine

There is little known about the state of equipment at Orpic and whether it presents any threats to safety and health of the organisation. The available information hints at the fact that Orpic both makes advances and lags in certain aspects. For instance, JCCP (2018) reports delays in clearing machinery/ equipment at Sohar Port. At the same time, recently, Orpic completed the installation of Oman’s first hydrocracker, which is supposed to take the safety and efficiency of production to the next level (Brelsford 2015).

McKinsey’s 7S Framework

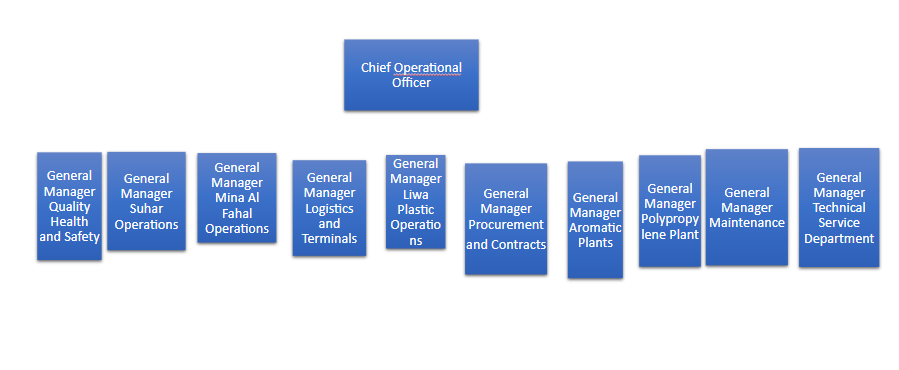

Now that the main causes of accidents in ORPIC have been identified, it is time to evaluate the organisational structure of the company’s excavation and rig maintenance department in order to determine how it contributes to the issues outlined in the previous section.

McKinsey’s 7S framework, as illustrated in Figure 2, enables the analysis of ORPIC’s departments using hard and soft elements, which determine the functionality of the organisational cluster. These elements are as follows (Stevens 2016):

Hard Elements

- Strategy. ORPIC’s business strategy revolves around providing its customers with the best balance of quantity and quality (Stevens 2016). However, the latest events and the company’s explosive growth rates show that the focus lies on increasing production outputs to satisfy the growing demand for petroleum products.

- Structure. The ORPIC’s excavation and rig maintenance department is a traditionally-organised hierarchical structure with a clear division of responsibilities and an established subordination system (Stevens 2016). Due to slowness in change adaptation, typical of oil and gas industry, ORPIC did not make significant changes to its structure in decades. The typical information and decision-making process is described as follows (Stevens 2016):

- Employee spots an issue;

- Line manager is informed. If the issue can be dealt with using their own resources – it is dealt with. If not – the middle manager is contacted, while all work goes on standby.

- Middle manager investigates the issue and allocates resources to fix the problem.

- Systems. The company has an integrated KPI system to tract worker and division progress. Some of the parameters relevant to excavation and maintenance include extracted barrels per day (bpd), accidents per quartal/year and budgetary expenditures (ORPIC 2015). Increased productivity, a lack of accidents and the ability to fit the budget are rewarded.

Soft Elements

- Skills. Departmental skills include the abilities to excavate and maintain gas and oil-rigging facilities, estimate potential issues with production and maintenance, evaluate the condition of the systems and provide damage control in the event of an accident (ORPIC 2015).

- Staff. The majority of employees is comprised of men aged 25-55 years old, with younger members occupying the lower bracket and performing hands-on labour, whereas older and distinguished employees often find themselves in the positions of leadership as line managers, middle managers and maintenance experts (Sumbal et al. 2017). All members of the workforce are expected to have an educational background in gas and petroleum-related disciplines, possess a high degree of functionality, punctuality and responsibility, while being capable of enduring the harsh conditions of employment (Sumbal et al. 2017).

- Style. There are high levels of disengagement in the lower tiers of the workforce. The most common complaints include high intensity of work, long shifts, uncomfortable weather conditions and outdated equipment. Line managers are often conflicting with both the employees and the middle managers due to not meeting the required production quotas (Berkowitz, Bucheli & Dumez 2017). Middle managers possess higher motivation and retention, but are often disconnected from the situation on the ground.

- Shared values. Based on the evaluation of the hard and soft elements presented above, it is possible to outline shared values of the organisation. It is a traditional top-down structure focused largely on increasing production values. The compensation system, although featuring several additional parameters, is largely focused on the short-term goals of receiving profit from higher quantities of delivered goods. The relationships between managers and employees revolve around completing the plan and maintaining budget parameters rather than ensuring the quality of life and labour.

Dissemination of Information

There is a connection between the existing rate of accidents and the overall organisational structure that the ORPIC’s excavation and rig maintenance department currently implements. As it was demonstrated in Figure 1, the major issues that lead to workplace accidents involve organisational inadequacy, poor work standards and force majeure events. The primary shared value of the department is economic efficiency, which is supported by the company’s resource-based management strategy.

It focuses on maximising profits in the short-term perspective and ensuring immediate growth rather than focusing on the existing assets. As a result, fuel production is the primary factor that counts. Employee training, specialised retention strategies, tools and systems upgrades, as well as organisational changes and risk protection are considered to be expenses that lower the yearly bottom line.

A risk factor that should be analyzed separately is leadership at Orpic. As McKinsey’s 7s shows, shared values is an aspect that ties all the others together, and one cannot imagine the effective realisation of values without sufficient leadership. Unfortunately, Orpic has yet to reach the optimal level of leadership. As of now, this goal is out of real due to the inadequate organisation and management.

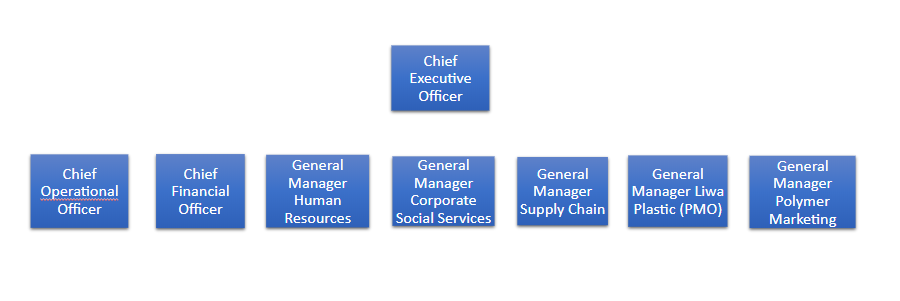

Even though, as a big corporation, the organisation has a comprehensive structure with distributed responsibilities (see Image 1 and 2), there is a lack of communication between the elements. Shared values cannot be efficiently communicated if different departments fail to share their concerns, ideas, and suggestions – something that good leaders need to moderate, control, and regulate. All five major risk factors that affect the accident rate can, therefore, be attributed to the short-term resource-based approach to extracting profit.

Literature Review

Accident Analysis Frameworks

At present, there are multiple accident analysis frameworks each of which has its own vices and virtues. For this research report, root cause analysis has been conducted. Embrey and Henderson (2004) define root cause analysis as a process aimed at understanding the underlying causes of accidents. Not only are the root causes located during RCA, but also their practical implications are defined. Therefore, it is fair to say that RCA meets two targets at once:

- explaining the causal relationships between the events;

- providing recommendations to manage the identified risks.

Causes of accidents have already been discussed in this section, but this distinction needs to be made one more time. As Embrey and Henderson (2004) show there are two approaches toward causality of accidents in the workplace. The individual based approach views each accident as a separate incident that is caused by a particular characteristic of the system or a person within it. For example, if a worker fails to comply with safety rules and causes an accident at the factory, the individual based-approach will explain the incident by the said worker’s inattentiveness and negligence.

As much as this conclusion may be fair to some extent, it falls short of the comprehension of a larger picture. This is what the system-based approach helps with: it sees accidents as being interlocked and connected to each other. The system-based approach prompts safety managers to wonder as to what exactly allowed an accident to happen. In this case, a particular worker’s negligence can be seen not only as an individual but also a collective issue: it is possible that the safety culture in the workplace was not enough to compel him or her to adopt safer methods of labor (Antonsen 2017).

This distinction helps Embrey and Henderson (2004) outline the key problems with RCA that this research paper is hopefully devoid of:

- focus on the individual rather than systemic causes;

- focus on the accident’s description as opposed to its causes;

- focusing on a single cause without taking into account all the possible causes.

Failing to address these three issues leads to inefficient safety strategies.

Another model that capitalises the connectivity and big thinking within an organisation is McKinsey’s 7s. This model was developed in the 1980s by McKinsey consultants and soon gained wide recognition by both academics and practitioners.

As of now, McKinsey’s 7s is one of the most popular strategic planning tools. What makes this model different and innovative is that it emphasises the essential role of human resources within an organisation (Soft S) as opposed to the traditional approach focusing on capital, infrastructure, and equipment. The goal of the model is to help to analyze seven elements of the company: Structure, Strategy, Skills, Staff, Style, Systems, and Shared values. The key point is that these elements are not isolated from each other. A change in one of them may have a network impact. 7s may be used together with the so-called fishbone or Ishikawa diagram. The latter aims at tracing back causes of undesired events, which facilitates locating connections.

Causes of Accidents

The key to efficient safety management is pinpointing the exact causes of accidents and addressing them in a timely manner. Bell and Healey (2006) provide a comprehensive systematic review of the existing research on the causes of accidents in different industries. Their work shows that there are a least a few categories of causes, each of which requires special investigation and management. The causes include but are not limited to:

- attitudinal and management factors. Bell and Healey (2006) cite an earlier publication by the University of Liverpool that shows exactly how poor management leads to the emergence of work hazards. Namely, attitudinal and management factors include maintenance errors, inadequate procedures, bad planning, and faulty risk assessment. Bell and Healey (2006) argue that accidents often stem from managers’ inability to control and monitor staff as well as educate and train them. On top of that, managers may often be aware of unsafe work conditions but decide to condone them;

- plant and process design. Bell and Healey (2006) show that in the nuclear, offshore, gas, and chemical industries, plants were often poorly designed to begin with, predisposing workers to experience frustration and make mistakes;

- communication issues. Another cause outlined by the researchers is breaks in communication and, therefore, low access to relevant information regarding safety;

- failure to investigate. Major hazards often stemmed from organisations’ inability to make the right conclusions and address risks;

- poor prioritisation. Several researchers cited by Bell and Healey (2006) pointed to managers’ failure to make safety one of the top priorities. Plants are often result-oriented, and in the pursuit of high performance, they may push workers past their threshold. Heavy workload may become another reason for creating dangerous situations.

What deserves special attention when it comes to safety management is the leverage of the human factor. Almost all works analyzed by Bell and Healey (2006) showed that the human error was one of the leading causes behind major accidents. The question arises as to exactly what in the human psyche makes people break rules and deviate from what they are prescribed to do. Probably the primary reason why the traditional safety management often fails to reach its goals is because it does not take into account the complexity of the human psyche. Previously, individuals in charge of safety management would rather operate on the premise that people are rational beings and tend to make rational choices.

However, today, a growing body of research reinforced by scientific advances in neurology and neuroscience shows this might not be the case. It appears that the primary source of motivation for humans lies in feelings and emotions as opposed to logical thoughts and ideas. This association between feelings and intention has the potential to shed light on the issue of workplace incidents and explain exactly why people often do not comply with the rules and act irrationally. DuPont (2015) claims that one may assume that when it comes to workplace situations, it might as well matter more how people “feel” about them and not how they “think” about them.

At present, neuroscience attributes humans’ overreliance on emotions to the vast amounts of information that people have to process on a daily basis. A workplace might be exactly the place where individuals have to deal with all kinds of data that needs to be filtered and prioritised in order to make decisions (Newell, Lagnado, & Shanks 2015). Humans monitor situations for potential risks or rewards, which is often rather emotion-based and might not make rational or logical sense. Some things go under the radar of humans’ attention and never trespass the threshold of their attention.

The question arises as to how people decide what deserves their focus and concentration and what does not. Arguably, if safety management will hinge on the premise of managing natural human patterns, it may as well ramp up its efficiency.

DuPont (2015) makes it a point to show that information about the environment is filtered based on the person’s previous experiences. Putting the issue again in the context of the workplace, one may say that individuals conduct cost-benefit analysis intuitively in their heads before making a decision. For instance, a worker in the oil and gas industry is confronted with a choice to comply with a safety rule or to neglect it.

In this case, the benefit of non-compliance might be doing the task in a way that is going to be easier for the worker. On the other hand, the risks of non-compliant behavior might include a fine, a disruption to the work process, an actual injury, or other undesired consequences. According to DuPont (2015), workers tend to choose to be involved in a risky activity based on whether they could get away with non-complying in the past without facing any kind of punishment or repercussions.

What also influences the decision-making process in this case is the stereotypes that a worker has regarding a certain work activity. Some jobs are perceived as safe, and Dell and Berkhout argue that this labeling might as well be dangerous.

Once a worker is convinced that a task is low-risk, he or she is likely to ignore safety rules and be negligent of the corporate guidelines. In this case, there is an anticipated outcome (positive), and a worker prefers to underestimate the actual risks. Lastly, there is always a schism between humans’ intuition and rational decision making (Beus, Dhanani, & McCord, 2015). All these facts from psychology and neuroscience may lay a solid theoretical foundation and provide practical implications for the modern safety management.

Due to the subject matter of the present research paper, it is important to draw attention to accident causes associated with the oil and gas industry specifically. Chadwell, Blundon, and Anderson (1997) provide a comprehensive report regarding root causes of oil and gas accidents in two geographical regions: the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific. Chadwell et al. (1997) draw a distinction between incident and fatality causes: the latter is a subgroup of the former but only includes the most grave causes.

The researchers discovered the following common incident causes in the descending order: equipment failure (46%), human error (35%), weather (7%), slip, trip, & fall (7%), and other (5%). However, what deserves the most attention about this report is the main causes of fatalities in the oil and gas industry. Chadwell et al. (1997) demonstrate that the leading cause is human error (37%), followed by slip, trip, & fall (36%). In contrast to incident causes, equipment failures were responsible only for every tenth fatality (9%). These statistics emphasise the importance of staff training when it comes to safety management.

Safety Culture

From the analysis of the key causes of accidents and the role of the human factor in the malfunctioning of the system, it becomes apparent that it suffices not to only treat the “symptoms” of the bigger issue. Surely, a company can and should provide a quick response in case of a force-majeure event or any kind of accident. However, as much as they can be effective, such measures are reactive in nature, meaning that they do not prepare the company for facing another undesired occurrence, let alone preventing it (Kim, Park, & Park, 2016).

Recent literature on safety management hints at the necessity of large-scale transformations as opposed to sporadic attempts at passing regulations and making changes (IOSH, 2015). At present, theorists and practitioners of safety management show the importance of building and promoting the so-called safety culture that should unite different departments of a company or an institution. Safety culture should serve as a point of reference for people’s behaviour and decision-making.

The question arises as to what exactly differentiates the creation of a corporate safety culture from merely passing and establishing guidelines and regulations. Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (n.d.) define culture as follows: “knowledge, values, norms, ideas and attitudes which characterise a group of people.” According to Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (n.d.), it is possible to gain an insight into corporate culture by listening to what workers say and observing what they actually put into action. In other words, a healthy safety culture means congruence between rules and behaviours. In recent years, Petroleum Safety Authority (n.d.) has come up with the so-called HSE culture, which stands for Health, Safety, and Environment. Officially, the requirements for a sound HSE culture include:

- the interconnectivity of the efforts aimed at improving the three important elements: health, safety, and environment;

- a good balance between the independent responsibility of every single worker and the responsibility of the enterprise to ensure sufficient working conditions.

Apart from the requirements, a positive safety culture entails three key elements:

- working rules and regulations for effectively controlling workplace hazards;

- high awareness of risk management and compliance with the guidelines;

- the capacity to learn from mistakes and past accidents (Petroleum Safety Authority Norway, n.d.).

Lastly, Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (n.d.) defines the four main properties of a positive safety culture: flexible, reporting, just, and learning. In alignment with these properties, a company or an institution needs to prioritise danger signaling and reports, which is made possible through communication and encouragement. The reaction to human errors should be proportionate to their gravity: workers should not be punished more harshly that they deserve. In addition, a company or an institution needs to be flexible enough to be able to incorporate the new regulations based on the accident reports and data and learn from past mistakes.

From the white paper provided by Petroleum Safety Norway (n.d.) it remains unclear what exactly helps to shape a safety culture and what, on the contrary, undermines its stability. Smith and Wadsworth (n.d.), two experts from the IOSH Research Committee explored the main contributors to safety culture. First and foremost, Smith and Wadsworth (n.d.) point out safety performance, which has shown the strongest correlation with safety culture in different industries. Addressing safety performance may be seen as somewhat problematic: the concept is too broad and nebulous to be easily quantified.

Smith and Wadsworth (n.d.) show that when it comes to measuring performance, organisations are often at the crossroads. On the one hand, analyzing the number of actual accidents, both minor and major, is a rigorous, positivist method of measuring performance. On the other hand, solely relying on hard data dismisses other important factors – risks and exposure to risk. In other words, it remains unclear how many accidents could have happened but didn’t, sometimes due to sheer luck.

Despite the nebulousness of some concepts, Smith and Wadsworth (n.d.) managed to apply scientifically rigorous frameworks and find associations that might be of value for organisations and institutions. First and foremost, safety performance operationalised as both the accident rate and safety behaviour was positively associated with safety culture. Another essential factor was individual awareness of safety culture, which makes the latter not something artificially imposed but a lived reality for workers. Lastly, the IOSH experts were able to demonstrate that safety advice benefits organisations in terms of nourishing safety culture. When companies reach out to safety experts to do audit, the have a chance of gaining an insight from qualified outsiders regarding their safety and risk management.

Management

When it comes to safety management, probably, the most challenging task is to translate knowledge into practice. Research hints at the necessity of continuous education and training of workers in order to promote safety culture and ensure compliance with the new rules (Zou & Sunindijo, 2015). DuPont (2015) puts forward quite an unusual idea in regards to risk management and staff training. The organisation claims that words and data have little to none influence on human behaviour. At first glance, this is quite a controversial opinion because in part, it negates the importance of safety training in the form in which they exist today.

However, later, DuPont (2015) elaborates on its hypothesis through an example. The experts argue that what many companies do wrong is labeling a behaviour “unsafe” even though the workers have been performing this exact task many times before. If this particular task has never yielded any negative repercussions for workers despite having the potential to do so, the managers are now at odds with actual experience. It becomes apparent that in actuality, logic and reason alone can only do so much in changing workers’ attitudes toward safety culture and building a new, safer environment.

Surely, the findings made by DuPont (2015) do not and should not undermine the importance of training altogether. Its claims only hint at the need to transform the paradigm and attitude toward training to make it fit a particular organisation’s expectations and the industry’s standards. Clarke and Flitcroft (n.d.) provide a comprehensive report regarding the effects of training in promoting a positive safety culture. The experts argue that in order to educate workers properly and yield long-term positive results, training should meet the following three requirements:

- training needs to be consistent with the company’s needs: there is no “one size fits all” recipe for success;

- rules and principles explained during training need to be an actual part of daily processes and procedures: workers should not see rules as sheer formality separated from what they usually do during the day;

- each organisation needs to make safety culture an indispensable part of its long term strategy.

The research carried out by Clarke and Flitcroft (n.d.) has clearly shown that if a training program complies with the outlined standards, it has all chances to be successful. The numbers speak for themselves: for instance, the accident rates dropped by 22% during the next 24 months after implementation took place. Moreover, employees’ perception of safety culture and their commitment to promote safe environment have also improved over time.

Overall, Clarke and Flitcroft (n.d.) concluded that the project was successful and met its goals. The only caveat discovered by researchers was that intensive training did not quite change employees’ perception of their managers. This finding should not be dismissed: for the sake of inference, one may assume that negative attitude toward the managing board may lead to miscommunication. As it has already been mentioned in this section, miscommunication is one of the most common accident causes that needs to be addressed.

Lastly, as recent research suggests, one of the key components of safety training and management should be leadership influence. Health and Safety Authority (n.d.) emphasise the importance of bringing leadership to the forefront of a company’s transformation. In particular, the institution discusses the many ways in which managers and other people in the decision-making positions influence employees’ behaviour:

- their behaviour acts as a frame of reference; they become a role model for their subordinates;

- employees sense whether managers are congruent in their words and actions;

- not only their actions but also their attitude contribute to the functioning or malfunctioning of the safety culture in the workplace;

- managers are able to motivate their subordinates, setting the mood for the entire workday.

Recommendations

In order to solve the issues related to worker safety and workplace accidents, the ORPIC’s excavation and rig maintenance department needs to change its perception towards value creation. As it stands, the emphasis lies on quantity, which is a decent strategy for expansion in a stable and friendly economic environment. However, with prices for oil remaining unstable due to the political situation in the Middle East, it would be prudent for ORPIC to adopt a different approach, which would, by extension, affect its accident rate. So far, it is possible to point out short-term, small-scale and long-term, large-scale measures that should be considered by Orpic.

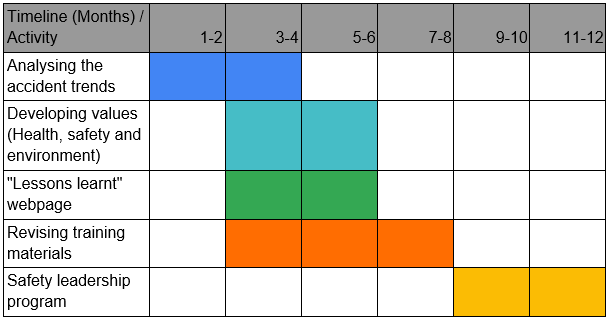

As seen from Table 1, the year 2019 should be marked with some changes in safety management training. The first important step is to make decisions regarding safety more data-driven by taking data collection more seriously. As it has been mentioned in the literature review, HSE culture is a learning culture. Therefore, it is only reasonable to start with learning from the past for building a better future. Another idea to consider is to question the existing values and see if they could be adjusted to fit the new direction that Orpic is bound to take to reduce the accident rate.

This may lead to the creation of the “Lessons learnt” page accessible to all employees so that they could ponder their own attitude toward safety management and use real-life cases to form their personal work ethics. Lastly, training materials need to be revised to make sure that managers and employees are educated in accordance with the latest industry’s standards. An intensive safety training program should crown this ambitious plan and serve as an important milestone for the company.

On a larger scale, the proposed changes are as follows (based on McKinsey’s 7s):

- Structure. Update the decision-making structure. As it stands, ORPIC operates using a traditional hierarchical model popular during the 1990s. Although it establishes clear responsibilities, it also removes the decision-making centres from the ground level, creating an information lag and the level of disconnection between line managers and middle-managers (Moody-Stuart 2017). The proposed solution is to shift the bulk of responsibilities to line managers, allowing them the authority to deal with safety issues on sight, while providing the resources necessary to do so.

- Strategy. Make safety management the key part of the global strategy as opposed to keeping it as nothing more than a sheer formality;

- Systems. Switch from quantity to quality. Installing new facilities, providing timely upgrades and investing in the employees and worker productivity will not only decrease the number of work safety-related incidents, but also provide the company with greater oil outputs in the long-term perspective (Redutskiy 2017);

- Skills. Invest in training of both managers and employees. Orpic has already invested into a safety leadership program that took place from July through August, 2019. The training was led by two experts: the founder of ETHOS EMPOWERMENT, Tom Keane, and the HSE professional and chartered engineer, Alan Izzard. The program sought to cover the three basic aspects of safety management: psychological, behavioural, and organisational. In alignment with these three aspects, three goals were developed: (1) to appeal to employees’ hearts and minds via leadership; (2) develop a clear understanding of the language of risk and address it; (3) question and challenge the existing structure that impedes the improvement of safety management. While an attempt as ambitious as the described training deserves to be acknowledged, one training is not likely to bring out major changes. Orpic needs to make continuing education one of its shared values and part of its strategy to yield positive long term results;

- Staff. Invest in appropriate HR strategies. The gas and oil industry worldwide is suffering from the “change of the crew” phenomenon, where the old generation of oil workers is approaching retirement and there are not enough young employees to replace them. Understaffing results in higher turnover rates, burnout and higher accident rates in employees, which leads to human, material and economic losses;

- Style. Introduce change management education to junior and senior management staff. The recommendations provided above require significant alterations to be made in the company’s and the department’s structures. Oil and gas industry is notorious for being one of the most change-resisting industries due to a large age gap and the lack of contemporary management education (Moody-Stuart 2017). Providing new ways of leadership, such as transformational or transitional types of leadership, is likely to make the organisation more prepared for the proposed changes;

- Shared values. Develop a safety-conscious workplace culture. As it stands, the ORPIC’s excavation and rig maintenance department is one of the most accident-prone elements of the company. The capability to spot issues early and report them to line managers lies almost entirely on vigilance of ground employees (Moody-Stuart 2017). At the same time, the knowledge of safety standards and requirements among them remains relatively subpar. Providing training and improving awareness is likely to reduce the number of safety-related accidents through direct prevention.

These are the primary suggestions that could be implemented in ORPIC’s division of choice or the organisation as a whole. Other departments are likely to have issues unique to their own specifications and peculiarities. For example, the financial department is unlikely to encounter any safety-related issues and should focus on efficiency and productivity instead.

Future Research Directions

The present research paper covers a wide variety of topics related to safety management at Orpic. It is possible that due to the large scope of the present research, some of the intricacies and particularities have been neglected or have not received due attention.

Future research on safety management at Orpic may concentrate on one of the aspects described in this paper. For instance, each of the parts of the Fishbone provided could be analyzed in more detail: man, method, environment, and others. As for future research design, one may envision two possible directions. Firstly, one may focus on the retrospective analysis, request more data, and proceed with locating the root causes of past incidents. At the same time, some other possible topics may include employee knowledge and attitude toward safety culture, managers’ awareness, and others.

Another compelling direction that future research may take is experimental. To truly gauge the efficiency of proposed solutions, one may want to put them to a test. For example, this paper emphasises the importance of training, education, and communication in building safety culture. Therefore, it would be useful to know whether these measures actually add value. One idea would be to evaluate the accident rate before and after safety training over the span of varying time periods. In summation, future research is bound to be more detailed and specific and aim to draw a fuller picture of what is happening at Orpic.

Conclusion

Oman Oil Refineries and Petroleum Industries Company is one of the largest and most rapidly-expanding companies in the region, amounting for over 15% of the country’s crude oil output and over 25% of its petroleum, plastic and polypropylene production. Nevertheless, it remains a high-risk industry for its employees due to various peculiarities of the company’s overarching goals and the general trends found in oil and gas industry.

The present research has proven to be consistent with the reviewed literature. First and foremost, it emphasized the significance of the human factor in the workplace. Secondly, both literary sources and research showed that leadership is required for making changes. The current strategy at Orpic is in alignment with the concept of HSE (health, safety, environment) in other countries. Lastly, some of the accidents may as well be attributed to faulty equipment, which is also mentioned in the review.

The situation at Orpic was evaluated using fishbone and McKinsey’s 7S frameworks. The proposed solutions to the problem include changing the overall strategic goals from quantity to quality, updating the technological assets of ORPIC, focusing on employee retention and changing the command structure to allow more organisational independence to line managers. The promotion of safety-focused working culture is also an important aspect of the proposed change.

The proposed solutions can be analyzed in terms of cost and impact and broken down into four categories as follows:

- high cost and high impact: updating the technological assets of ORPIC;

- low cost and high impact: employee retention and changing the command structure;

- low cost and low (short-term) impact: promoting safety-focused working culture;

- high cost and low impact: none as all of the proposed solutions were selected on the grounds of their viability and efficiency.

Most of the proposed solutions are unlikely to be fully implemented in the scope of one year, but a combination of initial efforts that do not require significant time and resources to utilise, such as change training and safety culture improvements, are likely to produce the required 10% results.

Way Forward

Although ORPIC is one of the major players in Oman’s energy and export strategy, it shares the majority of weaknesses with other companies in the industry, both inside and outside of the company. A literature review shows similar traits in American, European, Russian and Chinese fuel giants that are connected to government economic and political interests in some way or measure. The evolution is taking place, but it will require time to transform the industry deeply stuck in the 20th century to modern standards.

Limitations of the Research

The current research is not devoid of certain limitations that may undermine its validity. First and foremost, this paper suffers from insufficient data on accidents at Orpic. In the digital era, it is still not uncommon even for big corporations to fail to log data in a comprehensive way, preparing it for further analysis. This applies to Orpic: while the present paper does contain some data on the most recent accidents, there is a lot of missing information, which may account for a certain incompleteness of the analysis. The lack of information undermines the validity of some claims, which may lead to recommendations missing the point. Another issue that has been mentioned in the literature review and that may apply to Orpic is the controversy of the very concept of safety performance. Orpic only publishes data on accidents that happened; however, there are such factors as risks and exposure to risky situations that go dismissed.

Reference List

Antonsen, S 2017, ‘Safety culture: theory, method and improvement’, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Berkowitz, H, Bucheli, M & Dumez, H 2017, ‘Collectively designing CSR through meta-organizations: a case study of the oil and gas industry’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 143, no. 4, pp. 753-769.

Bell, J, and Healey, N 2006, The causes of major hazard incidents and how to improve risk control and health and safety management: a review of the existing literature.

Beus, JM, Dhanani, LY and McCord, MA 2015, ‘A meta-analysis of personality and workplace safety: Addressing unanswered questions’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 100, no. 2, p. 481.

Brelsford, Robert 2015, ORPIC completes installation of Oman’s first hydrocracker.

Chadwell, LJ, Blundon, C & Anderson, C 1997, Incidents associated with oil and gas operations.

Challenges facing ORPIC growth 2014. Web.

Channon, DF and Caldart, AA 2015, McKinsey 7S model, Wiley encyclopedia of management, pp.1-1.

Clark, S, and Flitcroft, C 2013, The effectiveness of training in promoting a positive OSH culture. Web.

Desai, KJ, Desai, MS & Ojode, L 2015, ‘Supply chain risk management framework: a fishbone analysis approach’, SAM Advanced Management Journal, vol. 80, no. 3, p. 34.

DuPont 2015, The human factor in safety and operations. How to change instinctive and habitual at risk behaviour.

Embrey, D, and Henderson, J 2004, Addressing the problems of Root Cause Analysis: a new approach to accident investigation.

Hamid, A, Baba, I and Sani, W 2017, ‘Risk management framework in oil field development project by enclosing fishbone analysis’, International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 446-452.

IOSH 2015, Promoting a positive culture. A guide to health and safety culture.

JCCP 2018, Challenges facing Orpic growth.

Kalyanam, S 2018, ‘Challenges of gas and oil mega-projects: Sugar refinery’, Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, pp. 12-15.

Kim, Y, Park, J and Park, M, 2016, ‘Creating a culture of prevention in occupational safety and health practice’, Safety and health at work, vol. 7, no. 2, pp.89-96.

Moody-Stuart, M 2017, Responsible leadership: lessons from the front line of sustainability and ethics, Routledge, New York, NY.

Newell, BR, Lagnado, DA and Shanks, DR 2015, Straight choices: The psychology of decision making, Psychology Press, London.

ORPIC 2015, Risk assessment report for petrochemical plant at Sohar. Web.

ORPIC 2019, Assets. Web.

Petroleum Safety Authority Norway n.d., HSE and Culture.

Orpic in pact to treat hazardous refinery waste 2017. Web.

Redutskiy, Y 2017, ‘Conceptualization of smart solutions in oil and gas industry’, Procedia Computer Science, vol. 109, pp. 745-753.

Smith, AP, and Wadsworth n.d., EJK Safety culture, advice and performance. Web.

Stevens, P 2016, Economic reform in the GCC: privatization as a panacea for declining oil wealth? Chatham House for the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham.

Stowell, F & Welch, C 2012, The manager’s guide to systems practice: making sense of complex problems, Wiley, New York, NY.

Sumbal, MS, Tsui, E, See-to, E & Barendrecht, A 2017, ‘Knowledge retention and aging workforce in the oil and gas industry: a multi perspective study’, Journal of Knowledge Management, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 907-924.

Zou, PX and Sunindijo, RY 2015, Strategic safety management in construction and engineering, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.